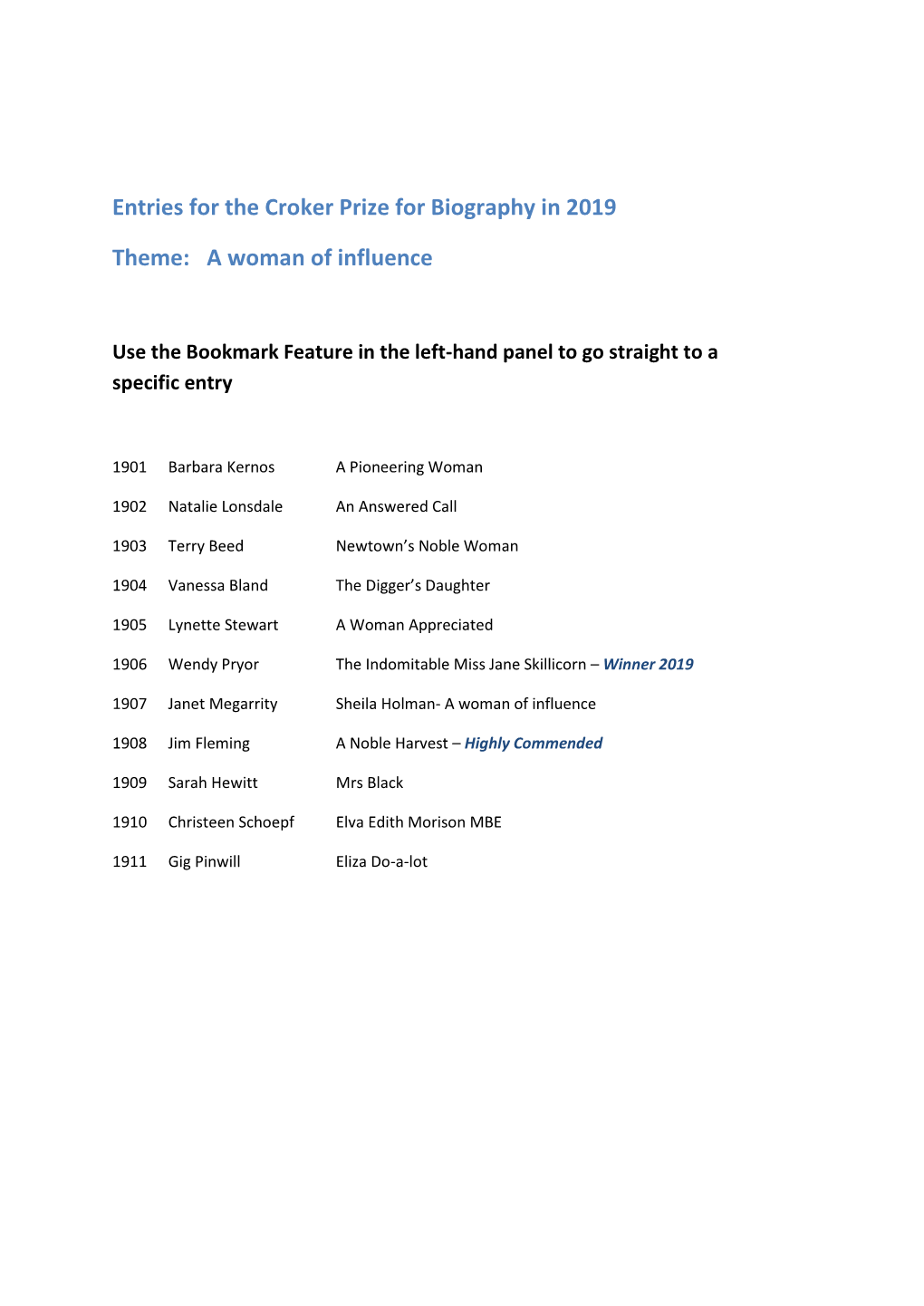

Entries for the Croker Prize for Biography in 2019 Theme: A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Media Tracking List Edition January 2021

AN ISENTIA COMPANY Australia Media Tracking List Edition January 2021 The coverage listed in this document is correct at the time of printing. Slice Media reserves the right to change coverage monitored at any time without notification. National National AFR Weekend Australian Financial Review The Australian The Saturday Paper Weekend Australian SLICE MEDIA Media Tracking List January PAGE 2/89 2021 Capital City Daily ACT Canberra Times Sunday Canberra Times NSW Daily Telegraph Sun-Herald(Sydney) Sunday Telegraph (Sydney) Sydney Morning Herald NT Northern Territory News Sunday Territorian (Darwin) QLD Courier Mail Sunday Mail (Brisbane) SA Advertiser (Adelaide) Sunday Mail (Adel) 1st ed. TAS Mercury (Hobart) Sunday Tasmanian VIC Age Herald Sun (Melbourne) Sunday Age Sunday Herald Sun (Melbourne) The Saturday Age WA Sunday Times (Perth) The Weekend West West Australian SLICE MEDIA Media Tracking List January PAGE 3/89 2021 Suburban National Messenger ACT Canberra City News Northside Chronicle (Canberra) NSW Auburn Review Pictorial Bankstown - Canterbury Torch Blacktown Advocate Camden Advertiser Campbelltown-Macarthur Advertiser Canterbury-Bankstown Express CENTRAL Central Coast Express - Gosford City Hub District Reporter Camden Eastern Suburbs Spectator Emu & Leonay Gazette Fairfield Advance Fairfield City Champion Galston & District Community News Glenmore Gazette Hills District Independent Hills Shire Times Hills to Hawkesbury Hornsby Advocate Inner West Courier Inner West Independent Inner West Times Jordan Springs Gazette Liverpool -

A Critical Biography of Henry Lawson

'From Mudgee Hills to London Town': A Critical Biography of Henry Lawson On 23 April 1900, at his studio in New Zealand Chambers, Collins Street, Melbourne, John Longstaff began another commissioned portrait. Since his return from Europe in the mid-1890s, when he had found his native Victoria suffering a severe depression, such commissions had provided him with the mainstay to support his young family. While abroad he had studied in the same Parisian atelier as Toulouse Lautrec and a younger Australian, Charles Conder. He had acquired an interest in the new 'plein air' impressionism from another Australian, Charles Russell, and he had been hung regularly in the Salon and also in the British Academy. Yet the successful career and stimulating opportunities Longstaff could have assumed if he had remained in Europe eluded him on his return to his own country. At first he had moved out to Heidelberg, but the famous figures of the local 'plein air' school, like Tom Roberts and Arthur Streeton, had been drawn to Sydney during the depression. Longstaff now lived at respectable Brighton, and while he had painted some canvases that caught the texture and tonality of Australian life-most memorably his study of the bushfires in Gippsland in 1893-local dignitaries were his more usual subjects. This commission, though, was unusual. It had come from J. F. Archibald, editor of the not fully respectable Sydney weekly, the Bulletin, and it was to paint not another Lord Mayor or Chief Justice, First published as the introduction to Brian Kiernan, ed., The Essential Henry Lawson (Currey O'Neil, Kew, Vic., 1982). -

'Settling in the Land of Wine and Honey: Cultural Tourism, Local

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by University of Southern Queensland ePrints ‘Settling in the Land of Wine and Honey: Cultural Tourism, Local History and Some Australian Legends.’ Christopher Lee University of Southern Queensland Rural mythology has historically provided an important focus for cultural explanations of Australian national identity. Since the early 1960s, however, rural myths – especially those represented through the Australian Legend -- have been subjected to searching critiques from different positions in and outside the Academy.1 The adoption of theoretical models during the 1980s and early 1990s that were interested in the politics of identity exposed the racial and gender bias of the rural legends associated with key Australian writers from the 1890s in particular.2 At the same time the apparent adoption of a form of identity politics in government policies related to migrants and the indigenous community, along with a simultaneous enthusiasm across the political spectrum for privatisation, deregulation, and globalisation, enabled a populist identification of the academic and intellectual class promoting these critiques with politicians, their policy advisers and the forces of global capital.3 Commentators in the metropolitan press and the academy have tended to argue that the new ‘racist’ and anti-intellectual political force mobilised by Pauline Hanson’s One Nation phenomenon represented an outdated anglo-celtic conservatism, which could be sourced to provincial -

RDA SA NEWS AUTUMN 2011 PAGE 2 Progress Slow and Steady at New O’Halloran Hill RDA Centre

RDARDA SASA NEWSNEWS Riding for the Disabled Association South Australia Inc. ISSUE NUMBER 32 AUTUMN 2011 Strong support for covered arena recent story in the Victor Harbor and is already before Victor Harbor Council‟s A Development Assessment Panel. Times has sparked some welcome It would be erected at the centre‟s riding area, on community support for a proposal to land sub-leased from Victor Harbor Riding Club. build an all-weather covered riding area The Times story by Anthony Caggiano quoted at the local RDA centre. centre president John Vincent, who said last year they A proposed 20 by 42.5m colorbond canopy with a had cancelled Tuesday and Saturday riding programs soft rubber/sand floor would cost around $120,000 six times because of rain or hot weather. Extreme weather can make things “severely uncomfortable for riders and volunteers,” he added. The Panel is considering possible issues with neighbours, whose backyards abut land on which the arena would be erected. Cr Peter Lewis spoke at the council meeting on March 28, stating he wanted to help the (RDA) group. Support also came from Cr Jim Telfer, who said effects on a newly built house next door would be “negligible”. Council approved the structure provided it met the requirements of the panel. Half the cost of the riding “arena” would come from a State government grant, the balance of around $60,000 being raised by the community. The structure would stand six metres tall and be shared between RDA and the Riding Club. John Vincent said both organisations could use it to conduct lessons and events during any type of weather. -

Victor Harbor Heritage Survey Volume 1

VICTOR HARBOR HERITAGE SURVEY VOLUME 1 SURVEY OVERVIEW November 1997 Donovan and Associates History and Historic Preservation Consultants P.O. Box 436, Blackwood, S.A. 5051 VICTOR HARBOR HERITAGE SURVEY VOLUME 1- Survey Overview VOLUME 2- Built Heritage VOLUME 3- Natural Heritage VICTOR HARBOR HERITAGE SURVEY 0 IO kw.S, VOLUME I 1. INTRODUCTION 1.1 OBJECTIVES 1-5 1.2 STUDY AREA 1-5 1.3 MEffiODOLOGY 1-6 1.4 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS 1-7 1.5 PROJECT TEAM 1-7 2. HISTORICAL BACKGROUND 1-8 2.1 PRE-HISTORY 1-9 2.2 EARLY HISTORY 1-9 2.3 EARLY WHITE SETTLEMENT 1-11 2.4 MARITIME DEVELOPMENT 1-17 2.5 LATE NINETEENTH CENTURY 1-33 DEVELOPMENT 2.6 EARLY TWENTIETH CENTURY 1-41 DEVELOPMENT 2.7 DEVELOPMENT AFTER WORLD WAR IT 1-59 3. RECOMMENDATIONS: BUILT HERITAGE 3.1 STATE HERITAGE PLACES 1-75 3.1.1 Victor Harbor-Suburban 1-75 3.2 STATE HERITAGE AREAS 1-75 3.3 PLACES OF LOCAL HERITAGE VALUE 1-75 3.3.1 Victor Harbor-Town Centre 1-75 3.3.2 Victor Harbor-Suburban 1-76 3.3.3 Victor Harbor-Environs 1-77 3.3.4 Bald Hills 1-77 3.3.5 Hindmarsh Valley!fiers 1-77 3.3.6 Inman Valley 1-77 3.3.7 Waitpinga 1-78 3.4 HISTORIC (CONSERVATION) ZONES 1-78 3.4.1 Victor Harbor-Town Centre 1-78 3.4.2 Victor Harbor-Suburban 1-78 4. RECOMMENDATIONS: NATURAL HERITAGE 4.1 NATIONAL ESTATE PLACES 1-80 4.1.1 Hundred of Encounter Bay 1-80 4.1.2 Hundred ofWaitpinga 1-80 4.2 STATE HERITAGE PLACES 1-80 4.2.1 Hundred of Encounter Bay 1-80 4.2.2 Hundred ofWaitpinga 1-80 4.3 PLACES OF LOCAL HERITAGE VALUE 1-80 4.3.1 Hundred of Encounter Bay 1-81 Donovan and Associates 1-2 4.3.2 Hundred of Goolwa 1-81 4.3.2 Hundred of Waitpinga 1-81 5. -

Thursday, 19 November 2020

No. 89 p. 5227 SUPPLEMENTARY GAZETTE THE SOUTH AUSTRALIAN GOVERNMENT GAZETTE PUBLISHED BY AUTHORITY ADELAIDE, THURSDAY, 19 NOVEMBER 2020 CONTENTS STATE GOVERNMENT INSTRUMENTS Constitution Act 1934 ............................................................. 5228 All instruments appearing in this gazette are to be considered official, and obeyed as such Printed and published weekly by authority of S. SMITH, Government Printer, South Australia $7.85 per issue (plus postage), $395.00 per annual subscription—GST inclusive Online publications: www.governmentgazette.sa.gov.au No. 89 p. 5228 THE SOUTH AUSTRALIAN GOVERNMENT GAZETTE 19 November 2020 STATE GOVERNMENT INSTRUMENTS CONSTITUTION ACT 1934 Order Making an Electoral Redistribution Notice is hereby given pursuant to Section 86 of the Constitution Act 1934, that the Electoral Districts Boundaries Commission has caused an order to be published making an electoral redistribution of the State’s 47 House of Assembly electoral districts. Any elector, as defined under Section 4 of the Electoral Act 1985, or the registered officer of any political party registered under Part 6 of the Electoral Act 1985, has a right to appeal against this order within 1 month of the publication in the Gazette being Thursday 19 November 2020. Dated: 18 November 2020 DAVID GULLY Secretary Electoral Districts Boundaries Commission 19 November 2020 THE SOUTH AUSTRALIAN GOVERNMENT GAZETTE No. 89 p. 5229 • SOUTH AUSTRALIA 2020 REPORT OF THE ELECTORAL DISTRICTS BOUNDARIES COMMISSION No. 89 p. 5230 THE SOUTH AUSTRALIAN GOVERNMENT GAZETTE 19 November 2020 CONTENTS The Order of the Commission Preliminary 2 1. The 2016 Redistribution and the 2018 Election results 5 2. Particular issues confronting the Commission during this redistribution 7 2.1 Introduction 7 2.2 Amendment to the Constitution Act 1934 (SA) 8 2.3 COVID-19 25 3. -

Henry Lawson - Poems

Classic Poetry Series Henry Lawson - poems - Publication Date: 2012 Publisher: Poemhunter.com - The World's Poetry Archive Henry Lawson(17 June 1867 – 2 September 1922) Henry Lawson was an Australian writer and poet. Along with his contemporary Banjo Paterson, Lawson is among the best-known Australian poets and fiction writers of the colonial period and is often called Australia's "greatest writer". He was the son of the poet, publisher and feminist <a href="http://www.poemhunter.com/louisa-lawson/">Louisa Lawson</a>. <b>Early Life</b> Henry Lawson was born in a town on the Grenfell goldfields of New South Wales. His father was Niels Herzberg Larsen, a Norwegian-born miner who went to sea at 21, arrived in Melbourne in 1855 to join the gold rush. Lawson's parents met at the goldfields of Pipeclay (now Eurunderee, New South Wales) Niels and Louisa married on 7 July 1866; he was 32 and she, 18. On Henry's birth, the family surname was anglicised and Niels became Peter Lawson. The newly- married couple were to have an unhappy marriage. Peter Larsen's grave (with headstone) is in the little private cemetery at Hartley Vale New South Wales a few minutes walk behind what was Collitt's Inn. Henry Lawson attended school at Eurunderee from 2 October 1876 but suffered an ear infection at around this time. It left him with partial deafness and by the age of fourteen he had lost his hearing entirely. He later attended a Catholic school at Mudgee, New South Wales around 8 km away; the master there, Mr. -

Chronology of Recent Events

AUSTRALIAN NEWSPAPER HISTORY GROUP NEWSLETTER ISSN 1443-4962 No. 31 February 2005 Compiled for the ANHG by Rod Kirkpatrick, 13 Sumac Street, Middle Park, Qld, 4074, Ph. 07-3279 2279, E-mail: [email protected] 31.1 COPY DEADLINE AND WEBSITE ADDRESS Deadline for next Newsletter: 30 April 2005. Subscription details appear at end of Newsletter. [Number 1 appeared October 1999.] The Newsletter is online through the “Publications” link from the University of Queensland’s School of Journalism & Communication Website at www.uq.edu.au/journ-comm/ and through the ePrint Archives at the University of Queensland at http://eprint.uq.edu.au/) Barry Blair, of Tamworth, NSW, and Victor Isaacs, of Canberra, are major contributors to this Newsletter. CURRENT DEVELOPMENTS: METROPOLITAN 31.2 FAIRFAX FOLLIES John Fairfax Holdings Ltd and its search for a new chief executive officer – to replace Fred Hilmer who announced last year that he would step down in 2005 – have been in the news constantly for more than a month, especially in the Australian. Tied in with the CEO search has been a report that Fairfax was keen to buy a stake in the Ten Network. Now read on: John Fairfax Holdings Ltd was negotiating secretly to buy a stake of up to $1 billion in the Ten Network before the Howard Government‟s planned changes to media ownership laws, the Australian reported (13 January 2005, p.1). Fairfax was one of a number of Australian-based media companies contacted by Ten Network‟s Canadian owner, CanWest, in the previous two months to gauge interest in buying a stake in the television network, the paper said. -

Interview with Ian Milnes on 21 July 2015

VICTOR HARBOR ORAL HISTORY PROJECT, ‘Beside the Seaside’ Interview with Ian Milnes on 21st July 2015 Interviewer: Keith Percival Ian is the fourth generation of the Milnes family involved in the printing industry. Welcome Ian and let’s start at the very beginning; when were you born and where? IM: Good afternoon Keith thank you. I was born in Victor Harbor on 10th December 1949, third son of Colin Milnes and Laurel Milnes of Victor Harbor. How many brothers and sisters did you have? IM: I have three brothers and one sister; I have two brothers older than me and a brother and sister younger than me. What work were your parents doing when you were born? IM: When I was born, my father Colin, or Ian Colin Milnes known as Colin Milnes, was a printer compositor editor at the Victor Harbor Times here in Victor Harbor and had been for a number of years. Did Mum help Dad? She wasn’t working was she? IM: No. Mum in those days, most wives were housewives essentially; Mother did not work, she was bringing up five children. Her hands were full. IM: Yes indeed. And your education Ian? IM: Educated at Victor Harbor Primary School, Victor Harbor High School as were my other siblings. Did you leave school at sixteen? IM: I finished school at the end of 1966; I’d just turned seventeen in December 1966 and enlisted in the Army in February 1967. We’ll come to the Army in a minute. IM: Certainly. Tell us your earliest memories of Ocean Street and Railway Terrace when you were a boy? IM: When I was growing up The Times was located in Coral Street, No 13 Coral Street, not Ocean Street, and as a young lad, generally on Saturday mornings Dad would take me around to The Times, he was always working Saturday mornings before he went off to golf. -

Mrs L, a Work of Literary Journalism, and Exegesis: the Poetics of Literary Journalism and Illuminating Absent Voices in Memoir and Biography

Mrs L, a work of literary journalism, and exegesis: The poetics of literary journalism and illuminating absent voices in memoir and biography. K.M Davies Department of Media and Communication University of Sydney September 2017 Thesis submitted in fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Arts (Literary Journalism) in Department of Media and Communications, University of Sydney 1 Statement of Originality I certify that the worK in this thesis has not previously been submitted for a degree nor has it been submitted as part of requirements for a degree except as fully acKnowledged within the text. I also certify that the thesis has been written by me. Any help that I have received in my research worK and the preparation of the thesis itself has been acKnowledged. In addition, I certify that all information sources and literature used are indicated in the thesis. This thesis has been prepared in accordance with Human Ethics Approval, University of Sydney: Project No: 2013/444. 2 Acknowledgements This thesis began as a memoir of single parenting that gradually became a worK of biography and theoretical reflection. I was encouraged to Keep researching and writing by Dr. Megan Le Masurier, Dr. Fiona Giles and Dr. Bunty Avieson at the Department of Media and Communications, University of Sydney. I was additionally given permission to view Ruth ParK’s unpublished notes about Bertha Lawson by Tim Curnow. I spent many hours researching at the State Library of NSW, the State Archives of NSW, the Fisher Library, University of Sydney and State Library Victoria, assisted by their wonderful librarians. -

Inspiring Womanhood a Re-Interpretation of the Dawn

Inspiring Womanhood A re-interpretation of The Dawn Hannah Louise Cameron 2011 Department of History, University of Sydney A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of Bachelor of Arts (Hons) in History. Abstract This thesis explores the diversity of content and ideas found in Louisa Lawson’s The Dawn, Australia’s first successful magazine ‘by women and for women’, showing that every element of the journal promoted a womanhood ideal for Australian women. Though remembered for the challenging arguments it made for women’s rights, most of the journal was taken up by beauty tips, household hints, recipes, women’s stories, health ideas, fashion articles and the like. This thesis examines such elements, noting how they served to help readers progress towards its womanhood ideal. It highlights the way that The Dawn’s discourse on women’s right was integrated into this ideal. It also analyses some of the key themes and ideas central to the ideal constructed in The Dawn, such as motherhood, beauty, and success in work and study. Acknowledgements I would like to thank my supervisor Associate-Professor Penny Russel for showing interest in and enthusiasm for my thesis this year despite already having what seemed a ridiculous workload. I thoroughly enjoyed all of our conversations about nineteenth century Australia and the history of Australian feminism. Your knowledge of Australian history is tremendous. Thank you for your patience and flexibility this year, as well as your clear guidance and helpful advice at every point. It was while studying one of your undergrad history courses that I decided to embark on an honours year, so I also thank you for this, and for setting challenging assessments which gave me the necessary skills to attempt a thesis. -

Sarsha Crawley

National winner Using archival records Sarsha crawley East Doncaster secondary college Louisa Lawson: Matriarch of Australian Feminism At the end of the nineteenth century, a social change was engulfing the Western World.1 Australia’s preparations to become a self-governing nation were put in fruition and the journey to become a new country encompassed the desire to bring with it a “new woman”. Conditions were horrendously discriminatory towards women leading up to and at the beginning of the twentieth century; however this was no deterrent for strong-willed and passionate women who campaigned tirelessly; first and foremost for the right of equal citizenship in the form of holding the privilege to vote.2 At the forefront of this movement, was Louisa Lawson, an inspiring and too often forgotten woman who changed Australia positively as a consequence of her tireless campaigning. Gold Rushes of the 1850’s in New South Wales saw poverty stricken convict families relocate with the prospect of fortune that gold would bring.3 Tents were assembled and quickly women were an underlying force, maintaining the domesticity. By the 1860’s, however, women had established themselves as pioneers of the land. Hard working labourers who married young and bared an average of seven children for the prosperity of the nation.4 It was at this time when women were confined to the women’s sphere, sewing for in excess of twelve hours a day, whilst maintaining a home and a family.5 It was this agonising and pain staking work that encouraged women to yearn for something different; to yearn for something more.