Polling a Third Party Challenger: Fact Or Artifact? Peter J Woolley, Dan Cassino

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Election Campaign 2009

Election Campaign 2009 Ad Populos, Non Aditus, Pervenimus Published Every Thursday Since September 3, 1890 (908) 232-4407 USPS 680020 Thursday, October 29, 2009 OUR 119th YEAR – ISSUE NO. 44-2009 Periodical – Postage Paid at Rahway, N.J. www.goleader.com [email protected] SIXTY CENTS Westfield Voters to Decide Mayor’s Race, Council Battles on Tuesday By PAUL J. PEYTON Assembly are up for grabs, with par- of Linden. Specially Written for The Westfield Leader ticular interest being focused locally on Other local races of interest in- WESTFIELD — Voters will decide District 22, where Democratic incum- clude Cranford, where incumbent the Westfield mayoral contest for the bents, Assemblywoman Linda Stender Committeeman David Robinson, a four-year term between incumbent Re- and Assemblyman Jerry Green, are re- Republican and the current mayor, is publican Andy Skibitsky and former ceiving a stiff challenge from GOP being opposed by Kevin Illing, who municipal judge Bill Brennan, a Demo- candidates former Scotch Plains Mayor lost a seat on the committee last year crat, as well as three contested races for Martin Marks and William “Bo” by under 100 votes. In Scotch Plains, seats on the town council on Tuesday. In Vastine, also of Scotch Plains. In Dis- incumbent Republican Councilman the First Ward, Republican Sam Della trict 21, Republicans Assemblyman Jon Dominick Bratti faces Democrat Fera faces Democrat Janice Siegel in the Bramnick and Assemblywoman Nancy Theresa Mullen for the remaining race to replace Councilman Sal Caruana; Munoz, who replaced her late husband, year on the seat previously held by Republican Vicki Kimmins is unopposed Eric, are opposed by Democratic Mayor Nancy Malool. -

2017 NJ Sustainability Summit -- Speakers

2017 NJ Sustainability Summit -- Speakers Helaine Barr, Research Scientist Bureau of Energy and Sustainability, NJ Department of Environmental Protection Helaine is committed to advancing sustainability principals and programs that support New Jersey’s communities and businesses. As a Research Scientist at the New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection (NJDEP), her responsibilities include coordination of the New Jersey Sustainable Business Registry, along with several other sustainability initiatives. Prior to joining the NJDEP she worked as an onsite consultant at the Philadelphia Water Department, leading major policy initiatives and programs for Philadelphia’s renowned Green City, Clean Waters program. Elyse Barone, Recycling and Clean Communities Coordinator Borough of Sayreville Elyse has been working as the Recycling and Clean Communities coordinator for the Borough of Sayreville for the past 6 years. She has lectured for Rutgers University in the Alternate Recycling Certification Program, Rutgers University’s Continuing Education series for Certified Recycling Professionals, and the New Jersey Clean Communities Council’s Clean Communities Coordinator Certification course. Elyse is a member of the Association of New Jersey Recyclers (A.N.J.R.), the Borough of Sayreville Environmental and Recycling Commissions and Green Team, and currently serves as the Coordinator for the Municipal Alliance as well as the County Alliance Steering Sub-Committee Chairperson. Last year Elyse won the 2016 NJ Clean Communities Excellence in Education Award. Adam Beam, Research Analyst Office of Energy and Climate Change Initiatives, Delaware Valley Regional Planning Commission Adam Beam is a Research Analyst in the Office of Energy and Climate Change Initiatives at the Delaware Valley Regional Planning Commission in Philadelphia. -

Music Student Wins Competition “Some of the Ideas We’Ve Talked About Are Student and Faculty Housing, As Well As by Raquel Fernandes Eugene J

runningback dawn & Lisa With change dish out the big read P. 3 advice P. 6 FALL FASHION of heart P. 15 SPECIAL The Tower see page 5 www.kean.edu/~thetower Kean University’s stUDENT NEWSPAPER Volume 10 • Issue 2 Oct. 21-Nov. 17, 2009 Transforming Morris Avenue? Kean University and Elizabeth Look at New Ideas BY JOSEPH TINGLE prise zone,” which the state designates to promote growth and private investment Kean University President Dawood through special tax breaks and other pro- Farahi and Chris Bollwage, mayor of the grams. Jersey Gardens Mall is in an urban city of Elizabeth, have a plan for Morris enterprise zone. Avenue that would permanently change “[The plan] would need to be a private- the atmosphere of Kean University and public partnership,” Bollwage said, and parts of its neighboring city. “will not work with [only] government The plan, which was announced briefly money.” by Dr. Farahi at a welcoming address to faculty and students last month, would create a student-centered “walking path” Photo: Ana Maria Silverman which would stretch from the intersection Chapolera Latin Musical Festival (See centerfold, pgs 8-9.) between Morris Avenue and North Avenue to the Elizabeth train station, and attract private investment to Kean and the city of Elizabeth, according to Bollwage. Music Student Wins Competition “Some of the ideas we’ve talked about are student and faculty housing, as well as BY RAQUEL FERNANDES Eugene J. Cornacchia and Dr. YiLi Lin, other businesses that are minimal to Kean the symphony’s conductor, signed a for- University, like bookstores and clothing Kean University music student Kenny mal agreement. -

Press Release

press release Website: www.grdodge.org Facebook: www.facebook.com/dodgefoundation Twitter: www.twitter.com/grdodge FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE – July 16, 2012 Contact: Molly de Aguiar (973) 540‐8442 ext. 156 or [email protected] GERALDINE R. DODGE FOUNDATION BOARD ANNOUNCES 99 GRANTS TOTALING $3.8 MILLION (Morristown, NJ) At its recent board meeting, the Trustees of the Geraldine R. Dodge Foundation approved 99 grants totaling $3.8 million to nonprofit organizations whose work in the arts, education, environment, and media fields significantly impacts communities throughout the state. “As we travel around the state, the resiliency and creativity of the nonprofit sector never cease to amaze us,” noted Dodge President and CEO Chris Daggett. “We know that the economy continues and will continue to present challenges and obstacles. Nonprofit organizations are faced with doing more with less, and are emerging with new and improved strategic and long‐range plans that address a range of new realities, both financial and programmatic.” HIGHLIGHTS OF THE GRANTS: ARTS The Dodge Foundation funds arts nonprofits which pursue and demonstrate the highest standards of artistic excellence in the performing and visual arts; enhance the cultural health and richness of communities; inspire learning and understanding; and contribute to New Jersey’s creative economy. A total of 45 Arts groups received $1,797,500 in this round of grants, including grants for Dance ($225,000), Music & Opera ($175,000), Theatre ($555,000), Visual Arts ($440,000) and organizations that help “Connect Community and the Arts” ($402,500). New grantees include 10 Hairy Legs, a new dance company under the artistic leadership of Randy James, and Newark Public Library, to support their exhibition of contemporary Newark art and photography in collaboration with local artists and galleries. -

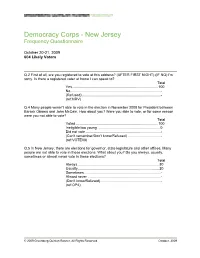

Frequency Questionnaire

Democracy Corps - New Jersey Frequency Questionnaire October 20-21, 2009 604 Likely Voters Q.2 First of all, are you registered to vote at this address? (AFTER FIRST NIGHT) (IF NO) I'm sorry. Is there a registered voter at home I can speak to? Total Yes ..................................................................................... 100 No..........................................................................................- (Refused)...............................................................................- (ref:NRV) Q.4 Many people weren't able to vote in the election in November 2008 for President between Barack Obama and John McCain. How about you? Were you able to vote, or for some reason were you not able to vote? Total Voted.................................................................................. 100 Ineligible/too young .............................................................. 0 Did not vote ...........................................................................- (Can't remember/Don't know/Refused) .................................- (ref:VOTE08) Q.5 In New Jersey, there are elections for governor, state legislature and other offices. Many people are not able to vote in these elections. What about you? Do you always, usually, sometimes or almost never vote in these elections? Total Always................................................................................. 80 Usually................................................................................. 20 Sometimes ............................................................................- -

Fusion Voting and the New Jersey Constitution: a Reaction to New Jersey’S Partisan Political Culture

MONGIELLO_FINAL.DOCX (DO NOT DELETE) 6/16/2011 3:01 PM FUSION VOTING AND THE NEW JERSEY CONSTITUTION: A REACTION TO NEW JERSEY’S PARTISAN POLITICAL CULTURE ∗ Jeffrey Mongiello Only by breaking the hold of the Democratic and Republican mandarins on the governor’s office and putting a rein on their power will the state have any hope for the kind of change needed to halt its downward economic, political and ethical spiral. New Jersey needs radical change in Trenton. Neither of the major parties is likely to provide it. [An independent candidate’s] elec- tion would send shock waves through New Jersey’s ossified politi- cal system and, we believe, provide a start in a new direction. It would signal the entrenched leadership of both parties and the interest groups they regularly represent that an ill-served and an- 1 gry electorate demands something better. I. INTRODUCTION In 2009, New Jersey’s largest newspaper endorsed an indepen- dent candidate for governor—not as an emphatic statement of sup- port for his policies, or as a rejection of the proposals (or lack the- reof) of the Democratic and Republican candidates, but rather as a strong denunciation of the two major parties themselves and the poli- tics they represent in New Jersey.2 The editorial identified a disillu- sioned electorate unsatisfied with the present state of affairs—a polit- ical system stuck in an ineffective status quo at the hands of the two major parties.3 In a state where unaffiliated voters represent the ∗ J.D. Candidate, May 2011, Seton Hall University School of Law; M.P.P. -

Bog Creek Farm Epa Id: Njd063157150 Ou 01 Howell Township, Nj 09/30/1985 Bog Creek Farm, Howell Township, New Jersey

EPA/ROD/R02-85/022 1985 EPA Superfund Record of Decision: BOG CREEK FARM EPA ID: NJD063157150 OU 01 HOWELL TOWNSHIP, NJ 09/30/1985 BOG CREEK FARM, HOWELL TOWNSHIP, NEW JERSEY. #DR DOCUMENTS REVIEWED I AM BASING MY DECISION ON THE FOLLOWING DOCUMENTS DESCRIBING THE ANALYSIS OF COST-EFFECTIVENESS OF REMEDIAL ALTERNATIVES FOR THE BOG CREEK FARM SITE: ! BOG CREEK FARM REMEDIAL INVESTIGATION REPORT, NUS CORPORATION, AUGUST 1985 ! BOG CREEK FARM FEASIBILITY STUDY OF ALTERNATIVES, NUS CORPORATION, SEPTEMBER 1985 ! STAFF SUMMARIES AND RECOMMENDATIONS ! RESPONSIVENESS SUMMARY, SEPTEMBER 1985. #DE DECLARATIONS CONSISTENT WITH THE COMPREHENSIVE ENVIRONMENTAL RESPONSE, COMPENSATION, AND LIABILITY ACT OF 1980 (CERCLA), AND THE NATIONAL OIL AND HAZARDOUS SUBSTANCES CONTINGENCY PLAN (NCP), 40 CFR PART 300, I HAVE DETERMINED THAT THE REMEDY DESCRIBED ABOVE IS AN OPERABLE UNIT INVOLVING CONTROL OF THE SOURCE OF THE CONTAMINATION WHICH IS COST-EFFECTIVE AND CONSISTENT WITH A PERMANENT REMEDY. IT IS HEREBY DETERMINED THAT IMPLEMENTATION OF THIS INTERIM REMEDIAL ACTION IS THE LOWEST COST ALTERNATIVE THAT IS TECHNOLOGICALLY FEASIBLE AND RELIABLE, AND WHICH EFFECTIVELY MITIGATES AND MINIMIZES DAMAGES TO AND PROVIDES ADEQUATE PROTECTION OF PUBLIC HEALTH, WELFARE AND THE ENVIRONMENT. IMPLEMENTATION OF THIS OPERABLE UNIT IS APPROPRIATE AT THIS TIME, PENDING A DETERMINATION OF THE NEED FOR ANY FURTHER REMEDIAL ACTIONS. IT IS ALSO HEREBY DETERMINED THAT THE SELECTED REMEDY IS APPROPRIATE WHEN BALANCED AGAINST THE AVAILABILITY OF TRUST FUND MONIES FOR USE AT OTHER SITES. THE STATE OF NEW JERSEY HAS BEEN CONSULTED AND AGREES WITH THE SELECTED REMEDY. SEPTEMBER 30, 1985 CHRISTOPHER J. DAGGETT DATE REGIONAL ADMINISTRATOR. SUMMARY OF REMEDIAL ALTERNATIVE SELECTION BOG CREEK FARM HOWELL, NEW JERSEY #SLD SITE LOCATION AND DESCRIPTION THE BOG CREEK FARM SITE IS LOCATED ON MONMOUTH COUNTY ROAD 547, ALSO CALLED THE LAKEWOOD-FARMINGDALE ROAD AND SQUANKUM ROAD, IN HOWELL TOWNSHIP, MONMOUTH COUNTY, NEW JERSEY. -

Raphael J. Caprio, Ph.D. EMPLOYMENT

Raphael J. Caprio, Ph.D. 76 North Finley Avenue Basking Ridge, NJ 07920 Business Phone: (848) 932-2422 Phone: (201) 323-3261 e-mail: [email protected] EMPLOYMENT January 1, 2012 - Present Rutgers University, New Brunswick, NJ 08901 University Professor, located at the Edward J. Bloustein School of Planning and Public Policy, Civic Square Building, 33 Livingston Avenue, New Brunswick, NJ 08901 Research Professor with emphasis on municipal and county finance and budgeting, real estate, property tax/ tax policy and public sector labor issues. Also, significant experience in NJ Interest Arbitration, having testi- fied in more than 120 cases over two decades. Teaching Responsibilities include Government Budgeting and Public Sector Management. Co-Executive Producer, “Due Process”. Rutgers University, NJTV, and WNET. 1996-2011 University Vice President for Continuing Studies, and Professor of Public Administration. Also concur- rently served as Interim University Chief Information Officer October 2002-June 2003. Rutgers University, 83 Somerset Street, Old Queens Room 306, New Brunswick, NJ, 08901. Reported to the Executive Vice President for Academic Affairs and University Budget Officer. Responsible for executive leadership for all university continuous education, distance learning, off-campus learning facili- ties, off-campus non-credit, credit, and degree programs, and university outreach efforts to non-traditional communities. Member of President’s Cabinet, Middle States Reaccreditation Steering Committee, others. Major units reporting -

Public Session Minutes

J E W R S E E N Election Y Law Enforcement Com missio n EL EC 1 973 State of New Jersey ELECTION LAW ENFORCEMENT COMMISSION JERRY FITZGERALD ENGLISH JEFFREY M. BRINDLE Chair Respond to: E xecutive Di rector P.O. Box 185 PETER J. TOBER Trenton, New Jersey 08625-0185 CAROL L. HOEKJE Vi ce Chai r Legal Director ALBERT BURSTEIN (609) 292-8700 or Toll Free Within NJ 1-888-313-ELEC (3532) EVELYN FORD Commissioner Compliance Director Website: http://www.elec.state.nj.us/ AMOS C. SAUNDERS JAMES P. WYSE Commissioner Legal Counsel PUBLIC SESSION MINUTES August 31, 2009 Chair English, Vice Chair Tober, Commissioner Burstein, Commissioner Saunders, and Legal Counsel Wyse participated by telephone. Executive Director Brindle, Legal Director Hoekje, and Director of Special Programs Amy Davis were present. The meeting convened at 2:00 p.m. in Trenton. 1. Open Public Meetings Statement Chair English called the meeting to order, and Executive Director Brindle announced that pursuant to the “Open Public Meetings Act,” N.J.S.A. 10:4-6 et seq., notice of this special telephonic meeting of the Election Law Enforcement Commission was announced for August 31, 2009, at 2:00 P.M., at the Commission’s offices, and was distributed at approximately 10:00 A.M. on August 27, 2009, to the entire State House press corps and was filed with the Secretary of State’s Office. It was also posted on the Commission’s website. Executive Director Brindle said that the Commission believes that it is in the public interest to act expeditiously upon an urgent matter of importance and of concern to the public interest about the dates of the 2009 general election gubernatorial debates and the 2009 general election lieutenant gubernatorial debate. -

Let Me Finish

Copyright Copyright © 2019 by Christopher J. Christie Jacket design by Amanda Kain Jacket copyright © 2019 by Hachette Book Group, Inc. Hachette Book Group supports the right to free expression and the value of copyright. The purpose of copyright is to encourage writers and artists to produce the creative works that enrich our culture. The scanning, uploading, and distribution of this book without permission is a theft of the author’s intellectual property. If you would like permission to use material from the book (other than for review purposes), please contact [email protected]. Thank you for your support of the author’s rights. Hachette Books Hachette Book Group 1290 Avenue of the Americas New York, NY 10104 hachettebooks.com twitter.com/hachettebooks First Edition: January 2019 Hachette Books is a division of Hachette Book Group, Inc. The Hachette Books name and logo are trademarks of Hachette Book Group, Inc. The publisher is not responsible for websites (or their content) that are not owned by the publisher. The Hachette Speakers Bureau provides a wide range of authors for speaking events. To find out more, go to www.hachettespeakersbureau.com or call (866) 376-6591. Print book interior design by Timothy Shaner, NightandDayDesign.biz Library of Congress Control Number: 2018956938 ISBNs: 978-0-316-42179-9 (hardcover), 978-0-316-42180-5 (ebook), 978-0-316-45412-4 (large print hardcover) E3-20181203-JV-NF-ORI CONTENTS COVER TITLE PAGE COPYRIGHT DEDICATION INTRODUCTION BANNON BLINKS PART ONE: BECOMING CHRIS 1. FAMILY VALUES 2. JERSEY BOY 3. LEARNING CURVE 4. HURRY UP PART TWO: CORRUPTION FIGHTER 5. -

![Marginals [PDF]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/9351/marginals-pdf-7319351.webp)

Marginals [PDF]

SUPRC EMBARGOED UNTIL 10:30 AM, 10/26 AREA N= 400 100% South .......................................... 1 ( 1/ 84) 67 17% Central ........................................ 2 98 25% North West ..................................... 3 58 15% North East...................................... 4 177 44% START Hello, my name is __________ and I am conducting a survey for Suffolk University and I would like to get your opinions on some political questions. We are calling New Jersey households statewide. Would you be willing to spend five minutes answering some brief questions? {ROTATE} N= 400 100% Continue ....................................... 1 ( 1/ 88) 400 100% S1 S1. Are you currently registered to vote? N= 400 100% Yes ............................................ 1 ( 1/ 89) 400 100% No ............................................. 2 0 0% GENDR Record Gender N= 400 100% Male ........................................... 1 ( 1/ 92) 182 46% Female ......................................... 2 218 54% S2 S2. Thank You. How likely are you to vote in the upcoming election for Governor? N= 400 100% Very likely .................................... 1 ( 1/ 93) 358 90% Somewhat likely ................................ 2 42 10% Not very/not at all likely ..................... 3 0 0% Other/Undecided/Refused ........................ 4 0 0% Q1 Q1. Which political party do you feel closest to - Democrat, Republican, or Independent? N= 400 100% Democrat ....................................... 1 ( 1/ 96) 135 34% Republican ..................................... 2 -

FROM CANDIDATE to GOVERNOR-ELECT Recommendations for Gubernatorial Transitions

FROM CANDIDATE TO GOVERNOR-ELECT Recommendations for Gubernatorial Transitions JULY 2017 Eagleton Center on the American Governor Eagleton Institute of Politics Summary of Recommendations PRE-TRANSITION: Issues to Address Prior to Election Day 1. Decide on size and structure of the Governor’s Office. 2. Select chief of staff. 3. Decide on all, or at least most, members of the central transition team. 4. Identify cabinet and other positions new governor will fill and start preparation of lists of potential candidates for specific positions. 5. Plan for desired transition-period interaction with the outgoing governor. 6. Develop goals and plans for possible lame duck legislative session. 7. Plan governor-elect’s immediate post-election schedule. 8. Write victory speech (and concession speech). THE TRANSITION: Issues That Must Be Addressed Prior to Inauguration 1. Contact the National Governors Association and party-specific governors association. 2. Consider whether to form subject-area transition committees. 3. Make key appointments. 4. Meet with legislative leaders as a group and individually. 5. Determine priority issues and pending decisions. 6. Determine goals for first 10 days, 100 days and perhaps other calendar markers. 7. Write inauguration speech. 8. Plan inauguration. 9. Decide which, if any, executive orders should be issued, overturned or changed on “Day One” and within first 30 days. 10. Develop framework for first budget message in February. 11. Understand that state “bureaucrats” can be your friends. DON’T MAKE PROMISES YOU MAY REGRET 1. Avoid early commitments to specific ethics reforms.. 2. Avoid early commitments to shrinking the size of the governor’s office.