Katie Healey

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Aaron David Stato Scarlatto Euroclub Abate Carmine La Collina Del Vento

aaron david stato scarlatto euroclub abate carmine la collina del vento mondadori abate carmine la festa del ritorno e altri viaggi mondolibri abbagnano nicola storia della filosofia,il pensiero greco e cri... gruppo editoriale l'espresso abécassis eliette il tesoro del tempio hachette abetti g. esplorazione dell'universo laterza abrami giovanni progettazione ambientale clup accoce pierre / quet pierre la guerra fu vinta in svizzera orpheus libri achard paul mes bonnes les editions de france ackermann walter en plein ciel librairie payot acton harold gli ultimi borboni di napoli martello adams douglas guida galattica per gli autostoppisti mondadori adams h. tre ragazze a londra malipiero adams richard i cani della peste rizzoli adams richard la ragazza sull'altalena narrativa club adams richard la valle dell'orso rizzoli adams scott dilbert (tm) la repubblica adamson joy regina di shaba club del libro adelson alan il diario di david sierakowiat einaudi adler david a. il mistero della casa stregata piemme junior adler elizabeth desideri privati speling & kupfer adler warren bugie private sperling paperback adler warren cuori sbandati euroclub adler warren la guerra dei roses berlusconi silvio editore adriani maurilio le religioni del mondo giunti-nardini Agassi, Andre Open la mia storia Giulio Einaudi Editore agee philip agente della cia editori riuniti agnellet michel cento anni di miracoli a lourdes mondadori arnoldo agnelli susanna vestivamo alla marinara mondadori Agnello Hornby, Simonetta La mia Londra Giunti Editore agostini franco giochi logici e matematici mondadori arnoldo editore agostini m.valeria europa comunitaria e partiti europei le monnier agrati gabriella / magini m.l.fiabe e leggende scozzesi (II vol.) mondadori agrati gabrielle / magini m.l.fiabe e leggende scozzesi (1 vol.) mondadori aguiar joao la stella a dodici punte le onde ahlberg allan dieci in un letto tea scuola ahrens dieter f. -

The Algerian War, European Integration and the Decolonization of French Socialism

Brian Shaev, University Lecturer, Institute for History, Leiden University The Algerian War, European Integration, and the Decolonization of French Socialism Published in: French Historical Studies 41, 1 (February 2018): 63-94 (Copyright French Historical Studies) Available at: https://read.dukeupress.edu/french-historical-studies/article/41/1/63/133066/The-Algerian- War-European-Integration-and-the https://doi.org/10.1215/00161071-4254619 Note: This post-print is slightly different from the published version. Abstract: This article takes up Todd Shepard’s call to “write together the history of the Algerian War and European integration” by examining the French Socialist Party. Socialist internationalism, built around an analysis of European history, abhorred nationalism and exalted supranational organization. Its principles were durable and firm. Socialist visions for French colonies, on the other hand, were fluid. The asymmetry of the party’s European and colonial visions encouraged socialist leaders to apply their European doctrine to France’s colonies during the Algerian War. The war split socialists who favored the European communities into multiple parties, in which they cooperated with allies who did not support European integration. French socialist internationalism became a casualty of the Algerian War. In the decolonization of the French Socialist Party, support for European integration declined and internationalism largely vanished as a guiding principle of French socialism. Cet article adresse l’appel de Todd Shepard à «écrire à la fois l’histoire de la guerre d’Algérie et l’histoire de l'intégration européenne» en examinant le Parti socialiste. L’internationalisme socialiste, basé sur une analyse de l’histoire européenne, dénonça le nationalisme et exalta le supranationalisme. -

In Historic Moment for Diocese of Fort Worth, Four Men Are Ordained As Priests by Kathy Cribari Hamer Correspondent News Reports Hailed It As “His- Toric,” and St

NorthBringing the Good News to the Diocese Texas of Fort Worth Catholic Vol. 23 No. 11 July 27, 2007 In historic moment for Diocese of Fort Worth, four men are ordained as priests By Kathy Cribari Hamer Correspondent News reports hailed it as “his- toric,” and St. Patrick Cathedral in downtown Fort Worth was overfl owing with the faithful who recognized the signifi cance of the grand event. But Bishop Kevin Vann elevated the ordina- tions of four priests by offering his refl ection on fi ve profoundly simple words: “I am a Catholic priest.” Thomas Kennedy, Raymond McDaniel, Isaac Orozco, and Jon- athan Wallis entered the Order of Presbyter July 7, and the Diocese of Fort Worth received its largest group of newly ordained priests since its founding in1969. Enthu- siasm for the event had reached all parts of the diocese, such that the viewing of the event had to be extended to an additional room in the Fort Worth Convention Center, where the liturgy was projected on a huge screen. Families and friends came to the ordination to experience the traditional liturgy concel- NEWLY ORDAINED — Bishop Kevin Vann is joined at the eucharistic table by the diocese’s four newly ordained priests, Father Jonathan Wallis (left), Father Isaac ebrated by clergy who came Orozco (left of bishop), Father Raymond McDaniel (right of bishop), and Father Thomas Kennedy (right). The men were ordained to the Order of the Presbyter July from throughout the extended 7 at St. Patrick Cathedral in downtown Fort Worth. It was the largest ordination class in the history of the Diocese of Fort Worth. -

Titolo Autore Editore 12 Anni Schiavo Northup Solomon Garzanti 2

Titolo Autore Editore 12 anni schiavo Northup Solomon Garzanti 2. Bambini e muri indiani Macchiavelli, Luca Milano Edizioni dell'arco ; Barzago : Marna, 2003 a caccia di belve hunter j.a. bompiani a che punto è la notte fruttero & lucentini club degli editori a ciascuno il suo sciascia leonardo la biblioteca di repubblica a ciascuno il suo corpo rodgers mary mondadori a colloquio con lech walesa gatter-klenk jule rusconi a dio piacendo ormesson jean rizzoli a est di bisanzio dunnett dorothy corbaccio a immagine di cristo,la vita secondo locorti spirito renato tip.san gaudenzio no a milano non fa freddo marotta giuseppe bompiani a occidente del pecos grey zane sonzogno a ogni morte di papa andreotti giulio rizzoli a ogni uomo un soldo marshall bruce longanesi & c. a piedi nudi bianco damiano ep publiep a prova di killer child lee superpocket a rischio cornwewll patricia mondadori a room of one's own woolf virginia gordon a sangue freddo capote t. garzanti a short history of nearly everything bryson bill doubleday a solo higgins jack club italiano dei lettori mila a tavola con il diabete tomasi franco a tavola nell'ossola di corato riccardo comunitàmontana valle ossola a un cerbiatto somiglia il mio amore grossman david mondolibri spa a volte ritornano king stephen bompiani a.belcastro 1893-1961 gnemmi dario saccardo ornavasso aarn munro il gioviano john w.campbell jr. editrice nord abbaiare stanca pennac daniel salani abbasso le più carine benton jim piemme spa abbracciata dalla luce eadie betty j. euroclub abissi benchley peter club degli editori absolute friends le carré john coronet books accabadora murgia michela einaudi accadde tutto in una notte clark mary higgins mondadori accademia carrara della chiesa angela ottino ist.ital.d'arti graf.bergamo accidenti! perché non mi guarda? rayban chloe mondadori accidenti,perché non mi vuoi capire...hopkins cathy mondadori accroche-toi à ton reve bradford barbara taylor pierre belfond acqua in bocca camilleri andrea minimum fax roma ad occhi chiusi carofiglio gianrico sellerio ed. -

San Diego Public Library New Additions June 2009

San Diego Public Library New Additions June 2009 Adult Materials 000 - Computer Science and Generalities California Room 100 - Philosophy & Psychology CD-ROMs 200 - Religion Compact Discs 300 - Social Sciences DVD Videos/Videocassettes 400 - Language eAudiobooks & eBooks 500 - Science Fiction 600 - Technology Foreign Languages 700 - Art Genealogy Room 800 - Literature Graphic Novels 900 - Geography & History Large Print Audiocassettes Newspaper Room Audiovisual Materials Biographies Fiction Call # Author Title FIC/ABRAMS Abrams, Douglas Carlton. The lost diary of Don Juan FIC/ADDIEGO Addiego, John. The islands of divine music FIC/ADLER Adler, H. G. The journey : a novel FIC/AGEE Agee, James, 1909-1955. A death in the family [MYST] FIC/ALBERT Albert, Susan Wittig. The tale of Briar Bank : the cottage tales of Beatrix Potter FIC/ALBOM Albom, Mitch, 1958- The five people you meet in heaven FIC/ALCOTT Alcott, Louisa May The inheritance FIC/ALLBEURY Allbeury, Ted. Deadly departures FIC/AMBLER Ambler, Eric, 1909-1998. A coffin for Dimitrios FIC/AMIS Amis, Kingsley. Lucky Jim FIC/ARCHER Archer, Jeffrey, 1940- A prisoner of birth [MYST] FIC/ARRUDA Arruda, Suzanne Middendorf The leopard's prey : a Jade del Cameron mystery [MYST] FIC/ASHFORD Ashford, Jeffrey, 1926- A dangerous friendship [MYST] FIC/ATHERTON Atherton, Nancy. Aunt Dimity slays the dragon FIC/ATKINS Atkins, Charles. Ashes, ashes [MYST] FIC/ATKINSON Atkinson, Kate. When will there be good news? : a novel FIC/AUSTEN Austen, Jane, 1775-1817. Emma FIC/BAGGOTT Baggott, Julianna. Girl talk [MYST] FIC/BAIN Bain, Donald, 1935- A slaying in Savannah : a Murder, she wrote mystery, a novel [MYST] FIC/BAIN Bain, Donald, 1935- A vote for murder : a Murder, she wrote mystery : a novel [MYST] FIC/BAIN Bain, Donald, 1935- Margaritas & murder : a Murder, she wrote mystery : a novel FIC/BAKER Baker, Kage. -

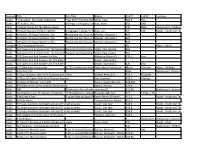

Elenco Libri in Ordine Alfabetico Per Titolo

ELENCO LIBRI IN ORDINE ALFABETICO PER TITOLO AGGIORNATO AL 21 GIUGNO 2013 Elenco libri in ordine alfabetico per titolo CODICE TITOLO AUTORE 8490 ... e la pioggia mia bevanda Suyin Han 3567 ... e la rosa - l'isola nel mondo Pini Adolfo 3318 ... e la vita continua Arlorio G. - Risi D. - Zapponi B. 5393 ... e poi non rimase nessuno Christie Agatha 9108 ... e venne chiamata due cuori Marlo Morgan 5832 ... e volen via! Brambilla Dugnani Paola 5771 ... e volen via! Dieci anni dopo Brambilla Dugnani Paola 5514 ... ricordiamo la pro magreglio … Romeo Maurizio 8003 007 licenza di avventura Fleming Jan 5360 007 licenza di uccidere Fleming Ian 3564 100 colpi di spazzola prima di andare a dormire Melissa P. 8821 101 modi per addormentare il tuo bambino rinaldi martina 8812 101 pezzi celebri classici e operistici rossi aldo 6734 101 storie zen Senzaki N - Reps P. 7671 150 anni andrea merzario Biagi E. - Folon J.M. - Roitier F. 7137 1882-1912: fare gli italiani Mola Aldo Alessandro 5733 1900-2000 - 100 anni di cronaca dal nostro territo autori vari 6570 1914 suicidio d'europa Romolotti Giuseppe 351 1915 obiettivo trento Pieropan Gianni 7124 1915-1917 guerra in ampezzo e cadore Berti Antonio 190 1917 lo sfondamento dell'isonzo Kraft Von Dellmensingen Konrad 1221 1919 la pace sbagliata Romolotti Giuseppe 7303 1943-1993 Biagi Enzo 7079 1983 anno santo della redenzione Carbone Mons.Carlo 7631 1990 il codice delle autonomie locali Sforza Fogliani C. - Maglia S. 1655 2 brave persone Cochi & Renato 5171 22 racconti d'amore da le mille e una notte Gabrielli Francesco 5478 25 anni di formula 1 Casucci P. -

Resource Typeitle Sub-Title Author Call #1 Call #2 Location Books

Resource TitleType Sub-Title Author Call #1 Call #2 Location Books "Impossible" Marriages Redeemed They Didn't End the StoryMiller, in the MiddleLeila 265.5 MIL Books "R" Father, The 14 Ways To Respond To TheHart, Lord's Mark Prayer 242 HAR DVDs 10 Bible Stories for the Whole Family JUV Bible Audiovisual - Children's Books 10 Good Reasons To Be A Catholic A Teenager's Guide To TheAuer, Church Jim. Y/T 239 Books - Youth and Teen Books 10 Habits Of Happy Mothers, The Reclaiming Our Passion, Purpose,Meeker, AndMargaret Sanity J. 649 Books 10 Habits Of Happy Mothers, The Reclaiming Our Passion, Purpose,Meeker, AndMargaret Sanity J. 649 Books 10 Habits Of Happy Mothers, The Reclaiming Our Passion, Purpose,Meeker, AndMargaret Sanity J. 649 Compact Discs100 Inspirational Hymns CD Music - Adult Books 101 Questions & Answers On The SacramentsPenance Of Healing And Anointing OfKeller, The Sick Paul Jerome 265 Books 101 Questions & Answers On The SacramentsPenance Of Healing And Anointing OfKeller, The Sick Paul Jerome 265 Books 101 Questions And Answers On Paul Witherup, Ronald D. 235.2 Paul Compact Discs101 Questions And Answers On The Bible Brown, Raymond E. Books 101 Questions And Answers On The Bible Brown, Raymond E. 220 BRO Compact Discs120 Bible Sing-Along songs & 120 Activities for Kids! Twin Sisters Productions Music Children Music - Children DVDs 13th Day, The DVD Audiovisual - Movies Books 15 days of prayer with Saint Elizabeth Ann Seton McNeil, Betty Ann 235.2 Elizabeth Books 15 Days Of Prayer With Saint Thomas Aquinas Vrai, Suzanne. -

Prek – 12 Religion Course of Study Diocese of Toledo 2018

PreK – 12 Religion Course of Study --- Diocese of Toledo --- 2018 PreK – 12 Religion Course of Study Diocese of Toledo 2018 Page 1 of 260 PreK – 12 Religion Course of Study --- Diocese of Toledo --- 2018 Page 2 of 260 PreK – 12 Religion Course of Study --- Diocese of Toledo --- 2018 TABLEU OF CONTENTS PreKU – 8 Course of Study U Introduction .......................................................................................................................7 PreK – 8 Content Structure: Scripture and Pillars of Catechism ..............................9 PreK – 8 Subjects by Grade Chart ...............................................................................11 Grade Pre-K ....................................................................................................................13 Grade K ............................................................................................................................20 Grade 1 ............................................................................................................................29 Grade 2 ............................................................................................................................43 Grade 3 ............................................................................................................................58 Grade 4 ............................................................................................................................72 Grade 5 ............................................................................................................................85 -

Downloads: Chuck Close Prints: Process and Collaboration by Terrie Sultan with Contributions from Richard Schiff Hardcover

US $25 The Global Journal of Prints and Ideas July – August 2014 Volume 4, Number 2 On Screenprint • The Theater of Printing • Arturo Herrera • Philippe Apeloig • Jane Kent • Hank Willis Thomas Ryan McGinness • Aldo Crommelynck • Djamel Tatah • Al Taylor • Ray Yoshida • Prix de Print: Ann Aspinwall • News C.G. Boerner is delighted to announce that a selection of recent work by Jane Kent is on view at the International Print Biennale, Hatton Gallery, Newcastle upon Tyne, June 27–August 8, 2014. Jane Kent, Blue Nose, 2013, silkscreen in 9 colors, 67 x 47 cm (26 ⅜ x 18 ½ inches) edition 35, printed and published by Aspinwall Editions, NY 23 East 73rd Street New York, NY 10021 www.cgboerner.com July – August 2014 In This Issue Volume 4, Number 2 Editor-in-Chief Susan Tallman 2 Susan Tallman On Screenprint Associate Publisher Susan Tallman and Michael Ferut 4 Julie Bernatz Screenprint 2014 Managing Editor Jason Urban 11 Dana Johnson Stagecraft: The Theater of Print in a Digital World News Editor Christine Nippe 15 Isabella Kendrick Arturo Herrera in Berlin Manuscript Editor Caitlin Condell 19 Prudence Crowther Type and Transcendence: Philippe Apeloig Online Columnist Sarah Kirk Hanley Treasures from the Vault 23 Mark Pascale Design Director Ray Yoshida: The Secret Screenprints Skip Langer Prix de Print, No. 6 26 Editorial Associate Peter Power Michael Ferut Ann Aspinwall: Fortuny Reviews Elleree Erdos Jane Kent 28 Hank Willis Thomas 30 Ryan McGinness 32 Michael Ferut 33 Hartt, Cordova, Barrow: Three from Threewalls Caitlin Condell 34 Richard Forster’s Littoral Beauties Laurie Hurwitz 35 Aldo Crommelynck Kate McCrickard 39 Djamel Tatah in the Atelier Jaclyn Jacunski On the Cover: Kelley Walker, Bug_156S Paper as Politics and Process 42 (2013-2014), four-color process screenprint John Sparagana Reads the News on aluminum. -

Xifaras, Theory of Legal Characters

THE THEORY OF LEGAL CHARACTERS MIKHAIL XIFARAS* INTRODUCTION ........................................................................ 1190 I. THE LEGAL STAGE (INTERLOCUTORY SPACE) ............... 1194 A. The Legality of the Situation .................................. 1194 B. Many Audiences, a Unique Legal Stage ................ 1195 C. Discourses Relevant for the TLC ............................ 1196 II. THE LEGAL CHARACTERS .............................................. 1197 A. The Theater Metaphor Applied to the Judicial Genre of Discourse .................................................. 1197 B. Daniel Mayer’s Inaugural Speech .......................... 1199 C. The Repertoire of Available Characters ................. 1200 D. Self-presentation and/or Narrative Syntax .......... 1201 E. Using the Actantial Model to Interpret the Deliberations of the CC ........................................... 1201 F. Repertoire of Available Characters for the Members of the CC .................................................. 1204 G. Beyond the “Actantial Model” ................................ 1208 III. THE PERFORMANCE OF LEGAL CHARACTERS ................ 1209 A. The Play of the Structure: The Life and Death of Legal Characters ..................................................... 1210 *Professor of Law, Sciences Po Law School. Multiple versions of the paper have been presented on various occasions: the Faculty Seminar of Sciences Po Law School (twice); the seminar Critical Analysis of Law of Toronto School of Law, led by M. Dubber and S. Stern; the Seminars Series of Glasgow’s Law School, led by A. Razulov and Ch. Tams; a colloquium led by M. Rosenfeld and P. Goodrich at The Cardozo School of Law; the QsQ6 Event at the Faculty of Law of the University of Toulouse, led by S. Mouton and X. Magnon; and the Seminar of the Laboratoire de Théorie du Droit at the Faculty of Law of the University of Aix, led by J.-Y. Cherot and F. Rouvière. I wish to thank all of the organizers and participants of these events for their great feedback and rich discussion. -

Reidocrea | Issn: 2254-5883 | Volumen 10

REIDOCREA | ISSN: 2254-5883 | VOLUMEN 10. NÚMERO 25. PÁGINAS 1-22 1 Estampación serigráfica: Antecedentes de la serigrafía Angélica Estefanía Romero Magallanes – Universidad Autónoma de Chihuahua 0000-0001-5494-3758 Recepción: 07.05.2021 | Aceptado: 21.06.2021 Correspondencia a través de ORCID: Angélica Estefanía Romero 0000-0001-5494-3758 Citar: Romero Magallanes, AE (2021). Estampación serigráfica: Antecedentes de la serigrafía. REIDOCREA,10(25), 1-22. Agradecimiento: Marisa Mancilla Abril, quien me otorgó su apoyo constante durante mi estadía en Granada y fue quien revisó mi trabajo y me otorgó una favorable retroalimentación. Mujer brillante, talentosa y amable a quien admiro profundamente. Gracias por ser una gran inspiración. Área o categoría del conocimiento: Artes Gráficas Resumen: El proceso de estampación serigráfica es una técnica artística muy joven comparada con las demás técnicas gráficas, que surge gracias a la aportación de diferentes procedimientos que tienen en común la utilización de una plantilla para generar una estampa, como el estarcido, que tiene orígenes ancestrales, y que evoluciona gracias a la aportación de los procedimientos de diferentes culturas. La serigrafía surge gracias a la aportación de diferentes patentes de creadores que buscaban generar plantillas solucionando el problema de los puentes entre las partes sueltas de la imagen (No era solo estético, era un problema muy serio que comprometía la viabilidad del proceso). En sus comienzos la serigrafía se utilizaba principalmente con fines industriales y publicitarios, pero los artistas descubrieron que podían utilizarla para generar obras con un valor estético, por lo que hubo una constante búsqueda por darle un lugar entre las técnicas gráfica, que se logra gracias al Pop Art, ya que los artistas americanos como Andy Warhol la utilizaron para generar obras que reflejaran su entorno y sociedad, influenciada por los medios de comunicación y el consumismo, dándole un lugar como técnica artística, y abriéndole paso dentro de museos de fama mundial. -

The British Left Intelligentsia and France Perceptions and Interactions 1930-1944

ROYAL HOLLOWAY UNIVERSITY OF LONDON DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY The British Left Intelligentsia and France Perceptions and Interactions 1930-1944 Alison Eleanor Appleby September 2013 Thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy 1 Declaration of Authorship I, Alison Appleby, confirm that this is my own work and the use of all material from other sources has been properly and fully acknowledged. Signed________________________________ Date__________________________________ 2 ABSTRACT This thesis is concerned with the ways in which the non-communist British left interacted with their French counterparts during the 1930s and the Second World War and described France in their writings and broadcasts. It challenges existing accounts that have described British attitudes to France as characterised by suspicion, ill-feeling or even contempt. It draws on a range of sources, including reportage, private papers, records of left-wing societies and other publications from the period, as well as relevant articles and books. The thesis explores the attitudes of British left-wing intellectuals, trade unionists and politicians and investigates their attempts to find common ground and formulate shared aspirations. The thesis takes a broadly chronological approach, looking first at the pre-1939 period, then at three phases of war and finally at British accounts of the Liberation of France. In the 1930s, British left-wing commentators sought to explain events in France and to work with French socialists and trade unionists in international forums in their search for an appropriate response to both fascism and Soviet communism. Following the defeat of France, networks that included figures from the British left and French socialists living in London in exile developed.