Accelerator Disaster Scenarios, the Unabomber, and Scientific Risks

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Remembering Alvin Tollestrup: 1924-2020 – CERN Courier

3/26/2020 Remembering Alvin Tollestrup: 1924-2020 – CERN Courier PEOPLE | NEWS Remembering Alvin Tollestrup: 1924-2020 6 March 2020 Alvin Tollestrup, who passed away on 9 February at the age of 95, was a visionary. When I joined his group at Caltech in the summer of 1960, experiments in particle physics at universities were performed at accelerators located on campus. Alvin had helped build Caltech’s electron synchrotron, the highest energy photon-producing accelerator at the time. But he thought more exciting physics could be performed elsewhere, and managed to get approval to run an experiment at Berkeley Lab’s Bevatron to measure a rare decay mode of the K+ meson. This was the rst time an outsider was allowed to access Berkeley’s machine, much to the consternation of Luis Alvarez and other university faculty. When I joined Alvin’s group he asked a postdoc, Ricardo Gomez, and me to design, build and test https://cerncourier.com/a/remembering-alvin-tollestrup-1924-2020/ 1/5 3/26/2020 Remembering Alvin Tollestrup: 1924-2020 – CERN Courier Machine maestro – Alvin Tollestrup led the pioneering a new type of particle detector called a spark work of designing and testing the superconducting magnets for the Tevatron, the rst large-scale chamber. He gave us a paper by two Japanese application of superconductivity. Credit: Fermilab authors on “A new type of particle detector: the discharge chamber”, not what he wanted, but a place to start. In retrospect it was remarkable that Alvin was willing to risk the success of his experiment on the creation of new technology. -

ANTIMATTER a Review of Its Role in the Universe and Its Applications

A review of its role in the ANTIMATTER universe and its applications THE DISCOVERY OF NATURE’S SYMMETRIES ntimatter plays an intrinsic role in our Aunderstanding of the subatomic world THE UNIVERSE THROUGH THE LOOKING-GLASS C.D. Anderson, Anderson, Emilio VisualSegrè Archives C.D. The beginning of the 20th century or vice versa, it absorbed or emitted saw a cascade of brilliant insights into quanta of electromagnetic radiation the nature of matter and energy. The of definite energy, giving rise to a first was Max Planck’s realisation that characteristic spectrum of bright or energy (in the form of electromagnetic dark lines at specific wavelengths. radiation i.e. light) had discrete values The Austrian physicist, Erwin – it was quantised. The second was Schrödinger laid down a more precise that energy and mass were equivalent, mathematical formulation of this as described by Einstein’s special behaviour based on wave theory and theory of relativity and his iconic probability – quantum mechanics. The first image of a positron track found in cosmic rays equation, E = mc2, where c is the The Schrödinger wave equation could speed of light in a vacuum; the theory predict the spectrum of the simplest or positron; when an electron also predicted that objects behave atom, hydrogen, which consists of met a positron, they would annihilate somewhat differently when moving a single electron orbiting a positive according to Einstein’s equation, proton. However, the spectrum generating two gamma rays in the featured additional lines that were not process. The concept of antimatter explained. In 1928, the British physicist was born. -

Sidney D. Drell Professional Biography

Sidney D. Drell Professional Biography Present Position Professor Emeritus, SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory, Stanford University (Deputy Director before retiring in 1998) Senior Fellow at the Hoover Institution since 1998 Present Activities Member, JASON, The MITRE Corporation Member, Board of Governors, Weizmann Institute of Science, Rehovot, Israel Professional and Honorary Societies American Physical Society (Fellow) - President, 1986 National Academy of Sciences American Academy of Arts and Sciences American Philosophical Society Academia Europaea Awards and Honors Prize Fellowship of the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation, November (1984-1989) Ernest Orlando Lawrence Memorial Award (1972) for research in Theoretical Physics (Atomic Energy Commission) University of Illinois Alumni Award for Distinguished Service in Engineering (1973); Alumni Achievement Award (1988) Guggenheim Fellowship, (1961-1962) and (1971-1972) Richtmyer Memorial Lecturer to the American Association of Physics Teachers, San Francisco, California (1978) Leo Szilard Award for Physics in the Public Interest (1980) presented by the American Physical Society Honorary Doctors Degrees: University of Illinois (1981); Tel Aviv University (2001), Weizmann Institute of Science (2001) 1983 Honoree of the Natural Resources Defense Council for work in arms control Lewis M. Terman Professor and Fellow, Stanford University (1979-1984) 1993 Hilliard Roderick Prize of the American Association for the Advancement of Science in Science, Arms Control, and International Security 1994 Woodrow Wilson Award, Princeton University, for “Distinguished Achievement in the Nation's Service” 1994 Co-recipient of the 1989 “Ettore Majorana - Erice - Science for Peace Prize” 1995 John P. McGovern Science and Society Medalist of Sigma Xi 1996 Gian Carlo Wick Commemorative Medal Award, ICSC–World Laboratory 1997 Distinguished Associate Award of U.S. -

People and Things

People and things Rafel Carreras of CERN - explaining science On people Joachim Heintze of Heidelberg re ceives the Max Bom Prize for his work in particle physics, particularly the investigation of the study of weak interactions and the develop ment of precision measurement techniques. The Max Born Prize is presented jointly by the UK Institute of Physics and the Deutsche Physikalische Gesellschaft. Rafel Carreras of CERN receives this year's popularization of science prize awarded by Geneva University and sponsored by the weekly 'Medecine et Hygiene'. His memora ble weekly 'Science for all' and monthly Science today' sessions at CERN attract good audiences, from Induction linac systems experiments Accelerator Instrumentation within CERN and from further afield. Workshop On 5 March, William Happer, Director Carl Ivar Branden from Uppsala has of the Office of Energy Research of The dates for the forthcoming Accel joined the European Synchrotron Ra the US Department of Energy, ap erator Instrumentation Workshop at diation Facility in Grenoble as Re proved a mission need statement for Berkeley have been fixed for 27-30 search Director, taking over from the Induction Linac Systems Experi October. Jim Hinkson and Greg Andrew Miller. ments (ILSE). Stover are co-chairmen. The ILSE project is needed to ad Meanwhile the deadline for nomi vance the understanding of high-cur nations for the Bergoz Faraday Cup rent, heavy-ion accelerator physics Award for innovative beam instru 10 Tesla magnet at Berkeley so that basic technical questions con mentation (January/February, page cerning the suitability of this ap 26) has been put back to 1 August. -

10.8 News 612 Mh

NEWS NATURE|Vol 442|10 August 2006 Views collide over fate of accelerator Its parts have been dismembered, its roof is leaking, and a wall is missing. Now activists and scientists are squabbling over whether to com- pletely raze the Bevatron — one of the most important particle accelerators ever built. The remains of the Bevatron, which was decommissioned more than a decade ago, take up prime real estate on the Lawrence Berkeley LAB. NATL BERKELEY LAWRENCE National Laboratory’s campus in Berkeley, Cali- fornia. Scientists at the lab want to tear it down to make way for fresh projects. But locals, many of whom oppose the demolition because of con- cerns about the possible release of contaminants, say they want to see it made into a museum. On 3 August, the city council’s Landmarks and Preservation Commission dealt a blow to those wanting landmark status for the accelera- tor by voting to recognize the Bevatron’s legacy without protecting the building. Nevertheless, landmark advocates have vowed to continue fighting. “It’s truly a landmark, a very unique building,” says Mark Divided: physicists up. Community members have expressed fears McDonald, who sits on the hope to reclaim the that razing the Bevatron would involve moving City of Berkeley’s Peace and space but local groups large amounts of loose asbestos through the city Justice Commission. “Some- want landmark status of Berkeley. Environmentalists also fear that body called it the world’s for the Bevatron. lead and other contaminants from the build- largest yurt.” The Bevatron, ing site could escape into the water table. -

Nuclear Spectroscopy ...I

SYMPOSIUM ON THE LAWRENCE RADIATION LABORATORY BY INVITATION OF THE COMMITTEE ON ARRANGEMENTS FOR THE AUTUMN MEETING Read before the Academy, November 8, 1958 Chairman, EDWIN L. MCMILLAN CONTENTS THE BEVATRON .................................. Edward J. Lofgren 451 FORCES BETWEEN NUCLEONS AND ANTINUCLEONS ...... Geoffrey F. Chewt 456 NUCLEAR SPECTROSCOPY .................................I . Perlman 461 RECENT WORK WITH THE TRANSURANIUM ELEMENTS ... Glenn T. Seaborg 471 THE BEVA TRON BY EDWARD J. LOFGREN LAWRENCE RADIATION LABORATORY, UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, BERKELEY Twenty-eight years ago, in the opening lines of a paper presented at a meeting of this academy, Prof. Lawrence said, "Very little is known about nuclear prop- erties of atoms, because of the difficulty inherent in excitation of nuclear transitions in the laboratory. The study of the nucleus would be greatly facilitated by the development of a source of high-speed protons having kinetic energy of about 1 million volt-electrons."' He went on to explain the idea of the cyclotron and the imminent possibility of producing 1-million-electron-volt protons with apparatus 10 cm in radius and having a 15,000-gauss magnetic field. Today a great deal is known about the nuclear properties of atoms, and much of this information came from the cyclotrons and related types of accelerators which stem directly from this early work of Prof. Lawrence. The Bevatron is one of the largest of this group of accelerators, and my purpose is to tell you what it is and how it works. Without apparent limit it seems that there is more and more to learn about nuclear particles. The experimental program of the Bevatron is one of the most important in this field, and in the following talk Prof. -

Mozart and Quantum Mechanics: an Appreciation of Victor Weisskopf

Physics Today Volume 56, No. 2, 43-47 (February 2003) Mozart and Quantum Mechanics: An Appreciation of Victor Weisskopf Weisskopf had a rare and harmonious blend of sentiment and intellectual rigor. He liked to say that his favorite occupations were Mozart and quantum mechanics. Kurt Gottfried and J. David Jackson Figure 1: Victor Weisskopf at about age 20 (photo courtesy of Duscha Scott Weisskopf) Victor Frederick Weisskopf, who died on 21 April 2002, was a leading figure in the second generation of theoretical physicists who expanded the reach of quantum mechanics following its discovery in 1925-26. That discovery proved to be the most profound and swift turning point in the history of physics since the time of Isaac Newton. Born in Vienna on 19 September 1908, Viki, as he was called by all who knew him, was too young to do original research in those first watershed years. But, like other outstanding members of his remarkable cohort, Viki was a fast study. He published his first landmark paper1 at the age of 22. Viki was eventually to become a major actor in a wide variety of settings, but all these roles were consequences of his achievements as a creative scientist. Therefore we devote here considerable attention to his contributions to fundamental theoretical physics. As a teenager, Viki became fascinated with astronomy and proudly listed a paper on the Perseid showers, based on a night's observation when he was not yet 15, as his first publication.2 The rich artistic and intellectual ambiance of pre-Nazi Vienna was to deeply influence his interests and attitudes throughout his life.3 Among his passions was music. -

The First Moment of Azimuthal Anisotropy in Nuclear Collisions From

The first moment of azimuthal anisotropy in nuclear collisions from AGS to LHC energies Subhash Singha, Prashanth Shanmuganathan and Declan Keane Department of Physics, Kent State University, Ohio 44242, USA (Dated: November 6, 2018) We review topics related to the first moment of azimuthal anisotropy (v1), commonly known as directed flow, focusing on both charged particles and identified particles from heavy-ion collisions. Beam energies from the highest available, at the CERN LHC, down to projectile kinetic energies per nucleon of a few GeV per nucleon, as studied in experiments at the Brookhaven AGS, fall within our scope. We focus on experimental measurements and on theoretical work where direct comparisons with experiment have been emphasized. The physics addressed or potentially addressed by this review topic includes the study of Quark Gluon Plasma, and more generally, investigation of the Quantum Chromodynamics phase diagram and the equation of state describing the accessible phases. arXiv:1610.00646v1 [nucl-ex] 3 Oct 2016 2 I. INTRODUCTION The purpose of relativistic nuclear collision experiments is the creation and study of nuclear matter at high energy densities. Experiments have established a new form of strongly-interacting matter, called Quark Gluon Plasma (QGP) [1{7]. Collective motion of the particles emitted from such collisions is of special interest because it is sensitive to the equation of state in the early stages of the reaction [8{10]. Directed flow was the first type of collective motion identified among the fragments from nuclear collisions [11{13], and in current analyses, is characterized by the first harmonic coefficient in the Fourier expansion of the azimuthal distribution of the emitted particles with respect to each event's reaction plane azimuth (Ψ) [14{16]: v1 = hcos(φ − Ψ)i; (1) where φ is the azimuth of a charged particle, or more often, the azimuth of a particular particle species, and the angle brackets denote averaging over all such particles in all events. -

University of California

I ' UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA JWO-WEEK LOAN COPY . This is a Library Circulating Copy which may be borrowed for two weeks. For a personal retention copy, call Tech. Info. Dioision, Ext. 5545 . ~. \ . ·; BERKELEY. CALIFORNIA .,.:; ~ ;y ", ' / - ~ 1'1 ,' . .. , I DISCLAIMER This document was prepared as an account of work sponsored by the United States Government. While this document is believed to contain correct information, neither the United States Government nor any agency thereof, nor the Regents of the University of California, nor any of their employees, makes any warranty, express or implied, or assumes any legal responsibility for the accuracy, completeness, or usefulness of any information, apparatus, product, or process disclosed, or represents that its use would not infringe privately owned rights. Reference herein to any specific commercial product, process, or service by its trade name, trademark, manufacturer, or otherwise, does not necessarily constitute or imply its endorsement, recommendation, or favoring by the United States Government or any agency thereof, or the Regents of the University of California. The views and opinions of authors expressed herein do not necessarily state or reflect those of the United States Government or any agency thereof or the Regents of the University of California. UCRL=3410 PhysiCs Distribution UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Radiation Laboratory Berkeley, California c~ Contract No. W-7405-eng-48 ~~.-~ ..·~·.,:,"'": ;+-•· .... 11. ...... , ~~... , . ' . PHYSICS DIVISION QUARTERLY REPORT February, March, April 1956 May22, 1956 Some of the results reported in this document may be of a preliminary or incomplete nature. The Radiation Laboratory requests that the document not be quoted without consultation with the author or the Information Division. -

Particle Physics and the Standard Model

., .,.,,,, ,, ,”. .,, ,:, L, weak force was invoked to understand the trans- mutation of a neutron in the nucleus into a proton during the particularly slow form of radioactive decay known as beta decay. Since neither the weak force nor the strong force is directly observed in the macroscopic world, both must be very short-range relative to the more familiar gravitational and electromagnetic forces. Furthermore, the relative strengths of the forces associated with all four interactions are quite dif- ferent, as can be seen in Table 1. It is therefore not too surprising that for a very long period these interactions were thought to be quite separate. In spite of this, there has always been a lingering suspicion (and hope) that in some miraculous fashion all four were simply manifestations of one source or principle and could therefore be de- scribed by a single unified field theory. Table 1 The four basic fcmes. Differences in stretr@m smwng the 1o-” square centimeter.) The stronger the force, the larger basic interactions are observed by comparhqg &tractdatic is the effective scattering area, or cross section, and the cross sections and particle lifetimes. (Cress sections are shorter tie lifetime of the particle state, At 1 GeV strong often expressed in barns beeause the cross-secthd mms ~MS tike Place 102 times faster than electromagnetic of nuclei are of this order of magnitude one barn equals ~rocesses and 10Stimes faster than weak processes. - 24 Summer/Fall 1984 LOS .4L.4MOS SCIENCE Particle Physics and the Standard Model THE STANDARD MODEL Interaction Strong Electroweak Local Symmetry SU(3) SU(2)X U(1) Coupling 9 T ‘d Matter Fields Quarks Quarks, Leptons, and Electrically Higgs Particles Charged Particles Gauge Fields Gluons W+, w-, zc’ Photon Conserved Quantities Coior CIsarga Etee@wrr f%msber Electric Bar~cn Number MswMsN4wnber Charge Tau Wsmber Fig. -

Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory Recent Work

Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory Recent Work Title PHYSICS DIVISION QUARTERLY REPORT Nov. Dec. 1954, Jan. 1955 Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/7ww9n680 Author Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory Publication Date 1955-03-15 eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UCRL 2920 UNClASSIFIED i( ••• - .-.,. ~ r~-........ • !>', ll, r · ' ·l . ' ' 'oilf.' ••, • .. 4:... UNIVERSITY OF •. l CALIFORNIA PHYSICS DIVISION QUARTERLY REPORT November, December . 1954, January 1955 TWO-WEEK LOAN COPY ! J ,:•. This is a Library Circulating Copy " which may be borrowed for two weeks. For a personal retention copy, call Tech. Info. Division, Ext. 5545 DISCLAIMER This document was prepared as an account of work sponsored by the United States Government. While this document is believed to contain correct information, neither the United States Government nor any agency thereof, nor the Regents of the University of California, nor any of their employees, makes any warranty, express or implied, or assumes any legal responsibility for the accuracy, completeness, or usefulness of any information, apparatus, product, or process disclosed, or represents that its use would not infringe privately owned rights. Reference herein to any specific commercial product, process, or service by its trade name, trademark, manufacturer, or otherwise, does not necessarily constitute or imply its endorsement, recommendation, or favoring by the United States Government or any agency thereof, or the Regents of the University of Califomia. The views and opinions of authors expressed herein do not necessarily state or reflect those of the United States Govemment or any agency thereof or the Regents of the University of Califomia. UCRL-2920 Unclassified Physics UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Radiation Laboratory Berkeley, California Contract No, W-7405-eng-48 . -

Historians and Scientists

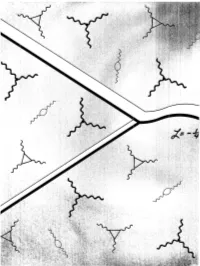

BOOK REVIEWS the written records, correcting the Energy Commission discovered that ura Historians and selective memories of the people who did nium prospecting was a more productive the work. On the question of why the way of building up stocks of nuclear fuel. scientists Berkeley Bevatron was built, Heilbron, a Cloud chambers, emulsions and Geiger counters were the principal particle detec David J. Miller historian, lists a complex of reasons, all of which were true at the time for some of tors for cosmic-ray work in 1947. By 1963, those participating in the decision. The accelerators had almost completely taken Pions to Quarks: Particle Physics in the particle physicists claim it was for the sake over, the bubble chamber had arrived, 1950s. Edited by Laurie M. Brown, Max of pure science, in particular to find the spark chambers were growing in impor Dresden and Lillian Hoddeson. Cam antiproton. But the Atomic Energy tance and new scintillating materials were bridge University Press: 1990. Pp. 734. Commission was also concerned to keep being used. There are first-hand accounts £40, $59.50. together Lawrence's team from the of how each of these techniques evolved. "Manhattan Engineering District" that Electronic computers began to appear "THE 1950s" are deemed to start in 1947 developed the atomic bomb, and to train and are mentioned in a few of the and end in 1963: from the discovery that the next generation of weapons research contributions, particularly in Luis pions, not muons, are the Yukawa par physicists. At about the same time, the Alvarez's dashing account of how he took ticles that carry the nuclear interaction, to Lawrence Livermore Laboratory was Glazer's idea of a small 'clean' glass the firm establishment of SU(3) theory.