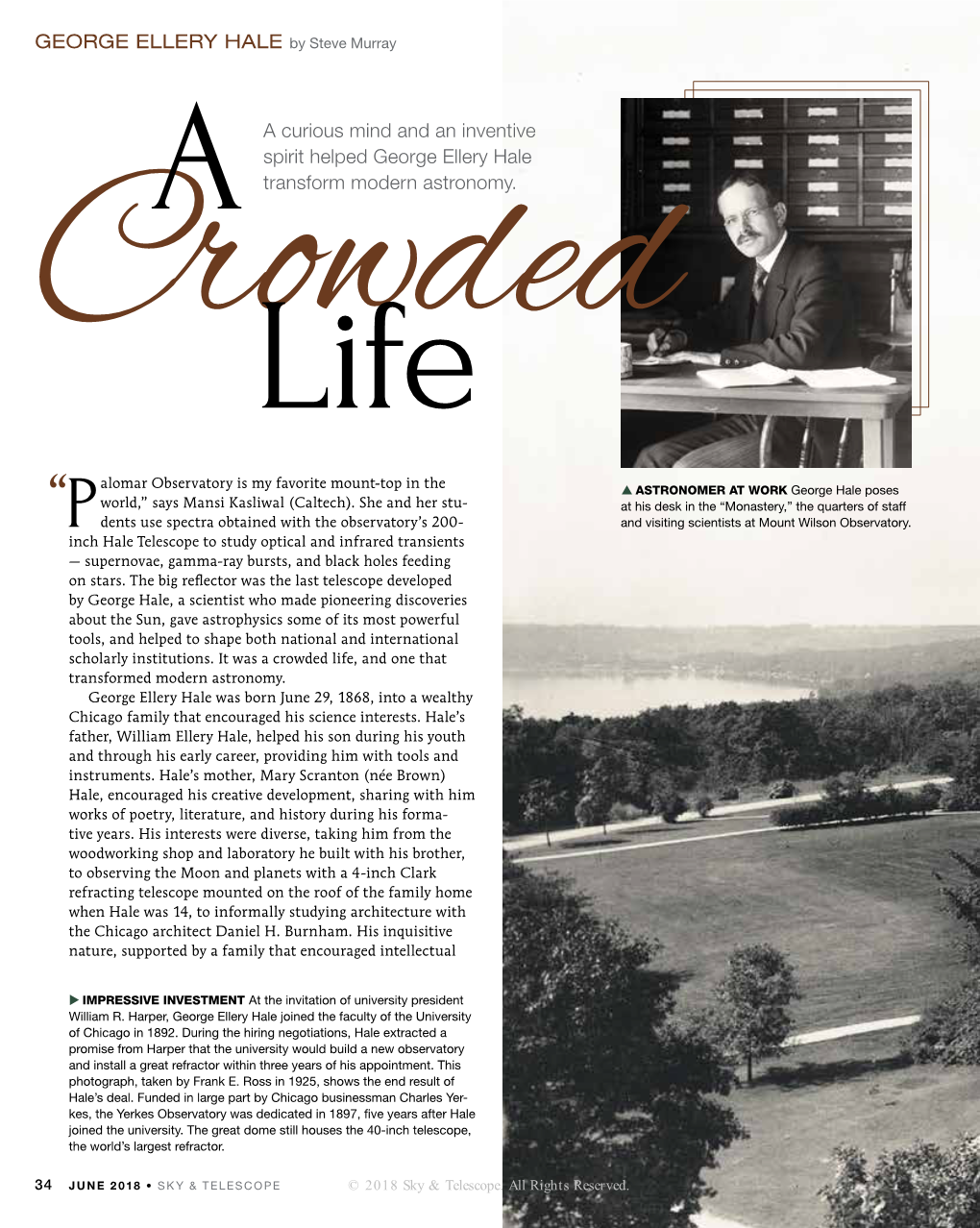

GEORGE ELLERY HALE by Steve Murray a Curious Mind And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Economic & Business History

This article was published online on April 26, 2019 Final version June 30, 2019 Essays in ECONOMIC & BUSINESS HISTORY The Journal of the Economic &Business History Society Editors Mark Billings, University of Exeter Daniel Giedeman, Grand Valley State University Copyright © 2019, The Economic and Business History Society. This is an open access journal. Users are allowed to read, download, copy, distribute, print, search, or link to the full texts of the articles in this journal without asking prior permission from the publisher or the author. http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ ISSN 0896-226X LCC 79-91616 HC12.E2 Statistics and London Underground Railways STATISTICS: SPUR TO PRODUCTIVITY OR PUBLICITY STUNT? LONDON UNDERGROUND RAILWAYS 1913-32 James Fowler The York Management School University of York [email protected] A rapid deterioration in British railways’ financial results around 1900 sparked an intense debate about how productivity might be improved. As a comparison it was noted that US railways were much more productive and employed far more detailed statistical accounting methods, though the connection between the two was disputed and the distinction between the managerial and regulatory role of US statistical collection was unexplored. Nevertheless, The Railway Companies (Accounts and Returns) Act was passed in 1911 and from 1913 a continuous, detailed and standardized set of data was produced by all rail companies including the London underground. However, this did not prevent their eventual amalgamation into the London Passenger Transport Board in 1933 on grounds of efficiency. This article finds that despite the hopes of the protagonists, collecting more detailed statistics did not improve productivity and suggests that their primary use was in generating publicity to influence shareholders’, passengers’ and workers’ perceptions. -

Edwin Powell Hubble Papers: Finding Aid

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/tf7b69n8rd Online items available Edwin Powell Hubble Papers: Finding Aid Processed by Ronald S. Brashear, completed December 12, 1997; machine-readable finding aid created by Xiuzhi Zhou and updated by Diann Benti in June 2017. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens Manuscripts Department 1151 Oxford Road San Marino, California 91108 Phone: (626) 405-2191 Email: [email protected] URL: http://www.huntington.org © 1998 The Huntington Library. All rights reserved. Edwin Powell Hubble Papers: mssHUB 1-1098 1 Finding Aid Overview of the Collection Title: Edwin Powell Hubble Papers Dates (inclusive): 1900-1989 Collection Number: mssHUB 1-1098 Creator: Hubble, Edwin, 1889-1953. Extent: 1300 pieces, plus ephemera in 34 boxes Repository: The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens. Manuscripts Department 1151 Oxford Road San Marino, California 91108 Phone: (626) 405-2191 Email: [email protected] URL: http://www.huntington.org Abstract: This collection contains the papers of Edwin P. Hubble (1889-1953), an astronomer at the Mount Wilson Observatory near Pasadena, California. as well as the diaries and biographical memoirs of his wife, Grace Burke Hubble. Language: English. Access Open to qualified researchers by prior application through the Reader Services Department. For more information, contact Reader Services. Publication Rights The Huntington Library does not require that researchers request permission to quote from or publish images of this material, nor does it charge fees for such activities. The responsibility for identifying the copyright holder, if there is one, and obtaining necessary permissions rests with the researcher. Preferred Citation [Identification of item]. -

The Origins of Political Electricity: Market Failure Or Political Opportunism?

THE ORIGINS OF POLITICAL ELECTRICITY: MARKET FAILURE OR POLITICAL OPPORTUNISM? Robert L. Bradley, Jr. * The current debate over restructuring the electric industry, which includes such issues as displacing the regulatory covenant, repealing the Public Utility Holding Company Act, and privatizing municipal power sys- tems, the Rural Utilities Service (formerly Rural Electrification Adminis- tration), and federally owned power systems, makes a look back at the origins of political electricity relevant. The thesis of this essay, that govern- ment intervention into electric markets was not the result of market fail- ures but, rather, represented business and political opportunism, suggests that the intellectual and empirical case for market-oriented reform is even stronger than would otherwise be the case. A major theme of applied political economy is the dynamics of gov- ernment intervention in the marketplace. Because interventions are often related, an analytical distinction can be made between basis point and cumulative intervention.' Basis point regulation, taxation, or subsidization is the opening government intervention into a market setting; cumulative intervention is further regulation, taxation, or subsidization that is attribu- table to the effects of prior (basis point or cumulative) intervention. The origins and maturation of political electricity, as will be seen, are interpret- able through this theoretical framework. The commercialization of electric lighting in the United States, suc- cessfully competing against gas lamps, kerosene lamps, and wax candles, required affordable generation, long distance transmission capabilities, and satisfactory illumination equipment. All three converged beginning in the 1870s, the most remembered being Thomas Edison's invention of the incandescent electric light bulb in 1878. - * Robert L. -

Telescopes and Binoculars

Continuing Education Course Approved by the American Board of Opticianry Telescopes and Binoculars National Academy of Opticianry 8401 Corporate Drive #605 Landover, MD 20785 800-229-4828 phone 301-577-3880 fax www.nao.org Copyright© 2015 by the National Academy of Opticianry. All rights reserved. No part of this text may be reproduced without permission in writing from the publisher. 2 National Academy of Opticianry PREFACE: This continuing education course was prepared under the auspices of the National Academy of Opticianry and is designed to be convenient, cost effective and practical for the Optician. The skills and knowledge required to practice the profession of Opticianry will continue to change in the future as advances in technology are applied to the eye care specialty. Higher rates of obsolescence will result in an increased tempo of change as well as knowledge to meet these changes. The National Academy of Opticianry recognizes the need to provide a Continuing Education Program for all Opticians. This course has been developed as a part of the overall program to enable Opticians to develop and improve their technical knowledge and skills in their chosen profession. The National Academy of Opticianry INSTRUCTIONS: Read and study the material. After you feel that you understand the material thoroughly take the test following the instructions given at the beginning of the test. Upon completion of the test, mail the answer sheet to the National Academy of Opticianry, 8401 Corporate Drive, Suite 605, Landover, Maryland 20785 or fax it to 301-577-3880. Be sure you complete the evaluation form on the answer sheet. -

Lillie Enclave” Fulham

Draft London Plan Consultation: ref. Chapter 7 Heritage - Neglect & Destruction February 2018 The “Lillie Enclave” Fulham Within a quarter mile radius of Lillie Bridge, by West Brompton station is A microcosm of the Industrial Revolution - A part of London’s forgotten heritage The enclave runs from Lillie Bridge along Lillie Road to North End Road and includes Empress (formerly Richmond) Place to the north and Seagrave Road, SW6 to the south. The roads were named by the Fulham Board of Works in 1867 Between the Grade 1 Listed Brompton Cemetery in RBKC and its Conservation area in Earl’s Court and the Grade 2 Listed Hermitage Cottages in H&F lies an astonishing industrial and vernacular area of heritage that English Heritage deems ripe for obliteration. See for example, COIL: https://historicengland.org.uk/listing/the-list/list-entry/1439963. (Former HQ of Piccadilly Line) The area has significantly contributed to: o Rail and motor Transport o Building crafts o Engineering o Rail, automotive and aero industries o Brewing and distilling o Art o Sport, Trade exhibitions and mass entertainment o Health services o Green corridor © Lillie Road Residents Association, February1 2018 Draft London Plan Consultation: ref. Chapter 7 Heritage - Neglect & Destruction February 2018 Stanford’s 1864 Library map: The Lillie Enclave is south and west of point “47” © Lillie Road Residents Association, February2 2018 Draft London Plan Consultation: ref. Chapter 7 Heritage - Neglect & Destruction February 2018 Movers and Shakers Here are some of the people and companies who left their mark on just three streets laid out by Sir John Lillie in the old County of Middlesex on the border of Fulham and Kensington parishes Samuel Foote (1722-1777), Cornishman dramatist, actor, theatre manager lived in ‘The Hermitage’. -

Researchers Hunting Exoplanets with Superconducting Arrays

Cryocoolers, a Brief Overview .............................. 8 NASA Preps Four Telescope Missions .............. 37 Lake Shore Celebrates 50 Years ....................... 22 ICCRT Recap ..................................................... 38 Recovering Cold Energy and Waste Heat ............ 32 3-D Printing from Aqueous Materials .................. 40 Exoplanet Hunt with ADR-Cooled Superconducting Detector Arrays | 34 Volume 34 Number 3 Researchers Hunting Exoplanets with Superconducting Arrays The key to revealing the exoplanets tucked away around the universe may just be locked up in the advancement of Microwave Kinetic Inductance Detectors (MKIDs), an array of superconducting de- tectors made from platinum sillicide and housed in a cryostat at 100 mK. An astronomy team led by Dr. Benjamin Mazin at the University of California Santa Barbara is using MKID arrays for research on two telescopes, the Hale telescope at Palomar Observatory near San Diego and the Subaru telescope located at the Maunakea Observatory on Hawaii. Mazin began work on MKIDs nearly two decades ago while working under Dr. Jonas Zmuidzinas at Caltech, who co-pioneered the detectors for cosmic microwave background astronomy with Dr. Henry LeDuc at JPL. A look inside the DARKNESS cryostat. Image: Mazin Mazin has since adapted and ad- vanced the technology for the direct im- aging of exoplanets. With direct imaging, telescopes detect light from the planet itself, recording either the self-luminous thermal infrared light that young—and still hot—planets give off, or reflected light from a star that bounces off a planet and then towards the detector. Researchers have previously relied on indirect methods to search for exo- planets, including the radial velocity technique that looks at the spectrum of a star as it’s pushed and pulled by its planetary companions; and transit pho- tometry, where a dip in the brightness of a star is detected as planets cross in front The astronomy team working with Dr. -

The JWST/Nircam Coronagraph: Mask Design and Fabrication

The JWST/NIRCam coronagraph: mask design and fabrication John E. Krista, Kunjithapatham Balasubramaniana, Charles A. Beichmana, Pierre M. Echternacha, Joseph J. Greena, Kurt M. Liewera, Richard E. Mullera, Eugene Serabyna, Stuart B. Shaklana, John T. Traugera, Daniel W. Wilsona, Scott D. Hornerb, Yalan Maob, Stephen F. Somersteinb, Gopal Vasudevanb, Douglas M. Kellyc, Marcia J. Riekec aJet Propulsion Laboratory/California Institute of Technology, 4800 Oak Grove Drive, Pasasdena, CA, USA 91109; bLockheed Martin Advanced Technology Center, Palo Alto, CA, USA 94303; cUniversity of Arizona, Tucson, AZ, USA 85721 ABSTRACT The NIRCam instrument on the James Webb Space Telescope will provide coronagraphic imaging from λ=1-5 µm of high contrast sources such as extrasolar planets and circumstellar disks. A Lyot coronagraph with a variety of circular and wedge-shaped occulting masks and matching Lyot pupil stops will be implemented. The occulters approximate grayscale transmission profiles using halftone binary patterns comprising wavelength-sized metal dots on anti-reflection coated sapphire substrates. The mask patterns are being created in the Micro Devices Laboratory at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory using electron beam lithography. Samples of these occulters have been successfully evaluated in a coronagraphic testbed. In a separate process, the complex apertures that form the Lyot stops will be deposited onto optical wedges. The NIRCam coronagraph flight components are expected to be completed this year. Keywords: NIRCam, JWST, James Webb Space Telescope, coronagraph 1. INTRODUCTION 1.1 The planet/star contrast problem Observations of extrasolar planet formation (e.g. protoplanetary disks) and planetary systems are hampered by the large contrast differences between these targets and their much brighter stars. -

Large Telescopes and Why We Need Them Transcript

Large telescopes and why we need them Transcript Date: Wednesday, 9 May 2012 - 1:00PM Location: Museum of London 9 May 2012 Large Telescopes And Why we Need Them Professor Carolin Crawford Astronomy is a comparatively passive science, in that we can’t engage in laboratory experiments to investigate how the Universe works. To study any cosmic object outside of our Solar System, we can only work with the light it emits that happens to fall on Earth. How much we can interpret and understand about the Universe around us depends on how well we can collect and analyse that light. This talk is about the first part of that problem: how we improve the collection of light. The key problem for astronomers is that all stars, nebulae and galaxies are so very far away that they appear both very small, and very faint - some so much so that they can’t be seen without the help of a telescope. Its role is simply to collect more light than the unaided eye can, making astronomical sources appear both bigger and brighter, or even just to make most of them visible in the first place. A new generation of electronic detectors have made observations with the eye redundant. We now have cameras to record the images directly, or once it has been split into its constituent wavelengths by spectrographs. Even though there are a whole host of ingenious and complex instruments that enable us to record and analyse the light, they are still only able to work with the light they receive in the first place. -

Francis Gladheim Pease Papers: Finding Aid

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/c8988d3d No online items Francis Gladheim Pease Papers: Finding Aid Finding aid prepared by Brooke M. Black, September 11, 2012. The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens Manuscripts Department 1151 Oxford Road San Marino, California 91108 Phone: (626) 405-2129 Email: [email protected] URL: http://www.huntington.org © 2012 The Huntington Library. All rights reserved. Francis Gladheim Pease Papers: mssPease papers 1 Finding Aid Overview of the Collection Title: Francis Gladheim Pease Papers Dates (inclusive): 1850-1937 Bulk dates: 1905-1937 Collection Number: mssPease papers Creator: Pease, F. G. (Francis Gladheim), 1881- Extent: Approximately 4,250 items in 18 boxes Repository: The Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens. Manuscripts Department 1151 Oxford Road San Marino, California 91108 Phone: (626) 405-2129 Email: [email protected] URL: http://www.huntington.org Abstract: This collection consists of the research papers of American astronomer Francis Pease (1881-1938), one of the original staff members of the Mount Wilson Solar Observatory. Language: English. Access Open to qualified researchers by prior application through the Reader Services Department. For more information, contact Reader Services. Publication Rights The Huntington Library does not require that researchers request permission to quote from or publish images of this material, nor does it charge fees for such activities. The responsibility for identifying the copyright holder, if there is one, and obtaining necessary permissions rests with the researcher. Preferred Citation [Identification of item]. Francis Gladheim Pease Papers, The Huntington Library, San Marino, California. Provenance Deposit, Observatories of the Carnegie Institution of Washington Collection , 1988. -

Demonstration of Vortex Coronagraph Concepts for On-Axis Telescopes on the Palomar Stellar Double Coronagraph

Demonstration of vortex coronagraph concepts for on-axis telescopes on the Palomar Stellar Double Coronagraph Dimitri Maweta, Chris Sheltonb, James Wallaceb, Michael Bottomc, Jonas Kuhnb, Bertrand Mennessonb, Rick Burrussb, Randy Bartosb, Laurent Pueyod, Alexis Carlottie, and Eugene Serabynb aEuropean Southern Observatory, Alonso de C´ordova 3107, Vitacura, Casilla 19001, Chile; bJet Propulsion Laboratory, California Institute of Technology, Pasadena, CA 91109, USA; cCalifornia Institute of Technology, Pasadena, CA 91106, USA; dSpace Telescope Science Institute, 3700 San Martin Drive, Baltimore, MD 21218, USA; eInstitut de Plan´etologieet d'Astrophysique de Grenoble (IPAG), University Joseph Fourier, CNRS, BP 53, 38041, Grenoble, France; ABSTRACT Here we present preliminary results of the integration of two recently proposed vortex coronagraph (VC) concepts for on-axis telescopes on the Stellar Double Coronagraph (SDC) bench behind PALM-3000, the extreme adaptive optics system of the 200-inch Hale telescope of Palomar observatory. The multi-stage vortex coronagraph (MSVC) uses the ability of the vortex to move light in and out of apertures through multiple VC in series to restore the nominal attenuation capability of the charge 2 vortex regardless of the aperture obscurations. The ring-apodized vortex coronagraph (RAVC) is a one-stage apodizer exploiting the VC Lyot-plane amplitude distribution in order to perfectly null the diffraction from any central obscuration size, and for any vortex topological charge. The RAVC is thus a simple concept that makes the VC immune to diffraction effects of the secondary mirror. It combines a vortex phase mask in the image plane with a single pupil-based amplitude ring apodizer, tailor-made to exploit the unique convolution properties of the VC at the Lyot-stop plane. -

Miller's Waves

Miller’s Waves An Informal Scientific Biography William Fickinger Department of Physics Case Western Reserve University Copyright © 2011 by William Fickinger Library of Congress Control Number: 2011903312 ISBN: Hardcover 978-1-4568-7746-0 - 1 - Contents Preface ...........................................................................................................3 Acknowledgments ...........................................................................................4 Chapter 1-Youth ............................................................................................5 Chapter 2-Princeton ......................................................................................9 Chapter 3-His Own Comet ............................................................................12 Chapter 4-Revolutions in Physics..................................................................16 Chapter 5-Case Professor ............................................................................19 Chapter 6-Penetrating Rays ..........................................................................25 Chapter 7-The Physics of Music....................................................................31 Chapter 8-The Michelson-Morley Legacy......................................................34 Chapter 9-Paris, 1900 ...................................................................................41 Chapter 10-The Morley-Miller Experiment.....................................................46 Chapter 11-Professor and Chair ...................................................................51 -

Albert Einstein: Relativity, War, and Fame Daniel J

Albert Einstein: Relativity, War, and Fame Daniel J. Kevles In , Princeton University Press published Albert Einstein’s The Meaning of Relativity, a popularization of his theory that has remained in print to this day, and that more than a half century ago Datus C. Smith, Jr., then the director of the Press, counted as one of its “crown jewels.”1 The book was the first in what has be- come a sizable number of volumes by and about Einstein that the Press has published, a number that continues to grow as succes- sive editions of his writings appear. Albert Einstein burst upon the world of physics in , at age twenty-six, when he was working as an examiner in the Swiss patent office in Bern and published three extraordinary scientific papers. One, speaking to the developing though somewhat con- troversial atomic theory of matter, demonstrated the reality of atoms and molecules. The other two—one advancing a quantum theory of light, the other proposing the special theory of rela- tivity—contributed decisively to the revolution in physics that marked the twentieth century. Two years later, in , Einstein began work on what became the general theory of relativity. The special theory discarded the assumption of Newtonian physics that there exists an absolute frame of reference in space against which all motion in the uni- verse can be measured. Taking no frame as privileged, it related how phenomena occurring in one inertial frame—that is, one moving at constant velocity—would appear in a second moving in relation to the first. The two frames might be, for example, two trains traveling at different constant speeds on neighboring tracks.