Finding Flourishing: the Well-Being Discovery Framework

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Research Brief March 2017 Publication #2017-16

Research Brief March 2017 Publication #2017-16 Flourishing From the Start: What Is It and How Can It Be Measured? Kristin Anderson Moore, PhD, Child Trends Christina D. Bethell, PhD, The Child and Adolescent Health Measurement Introduction Initiative, Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Every parent wants their child to flourish, and every community wants its Public Health children to thrive. It is not sufficient for children to avoid negative outcomes. Rather, from their earliest years, we should foster positive outcomes for David Murphey, PhD, children. Substantial evidence indicates that early investments to foster positive child development can reap large and lasting gains.1 But in order to Child Trends implement and sustain policies and programs that help children flourish, we need to accurately define, measure, and then monitor, “flourishing.”a Miranda Carver Martin, BA, Child Trends By comparing the available child development research literature with the data currently being collected by health researchers and other practitioners, Martha Beltz, BA, we have identified important gaps in our definition of flourishing.2 In formerly of Child Trends particular, the field lacks a set of brief, robust, and culturally sensitive measures of “thriving” constructs critical for young children.3 This is also true for measures of the promotive and protective factors that contribute to thriving. Even when measures do exist, there are serious concerns regarding their validity and utility. We instead recommend these high-priority measures of flourishing -

The Origin of the Peculiarities of the Vietnamese Alphabet André-Georges Haudricourt

The origin of the peculiarities of the Vietnamese alphabet André-Georges Haudricourt To cite this version: André-Georges Haudricourt. The origin of the peculiarities of the Vietnamese alphabet. Mon-Khmer Studies, 2010, 39, pp.89-104. halshs-00918824v2 HAL Id: halshs-00918824 https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-00918824v2 Submitted on 17 Dec 2013 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Published in Mon-Khmer Studies 39. 89–104 (2010). The origin of the peculiarities of the Vietnamese alphabet by André-Georges Haudricourt Translated by Alexis Michaud, LACITO-CNRS, France Originally published as: L’origine des particularités de l’alphabet vietnamien, Dân Việt Nam 3:61-68, 1949. Translator’s foreword André-Georges Haudricourt’s contribution to Southeast Asian studies is internationally acknowledged, witness the Haudricourt Festschrift (Suriya, Thomas and Suwilai 1985). However, many of Haudricourt’s works are not yet available to the English-reading public. A volume of the most important papers by André-Georges Haudricourt, translated by an international team of specialists, is currently in preparation. Its aim is to share with the English- speaking academic community Haudricourt’s seminal publications, many of which address issues in Southeast Asian languages, linguistics and social anthropology. -

Applications the Formula Y = Mx + B Sometimes Appears with Different

PRIMARY CONTENT MODULE Algebra I -Linear Equations & Inequalities T-71 Applications The formula y = mx + b sometimes appears with different symbols. For example, instead of x, we could use the letter C. Instead of y, we could use the letter F. Then the equation becomes F = mC + b. All temperature scales are related by linear equations. For example, the temperature in degrees Fahrenheit is a linear function of degrees Celsius. © 1999, CISC: Curriculum and Instruction Steering Committee The WINNING EQUATION PRIMARY CONTENT MODULE Algebra I -Linear Equations & Inequalities T-72 Basic Temperature Facts Water freezes at: 0°C, 32°F Water Boils at: 100°C, 212°F F • (100, 212) • (0, 32) C Can you solve for m and b in F = mC + b? © 1999, CISC: Curriculum and Instruction Steering Committee The WINNING EQUATION PRIMARY CONTENT MODULE Algebra I -Linear Equations & Inequalities T-73 To find the equation relating Fahrenheit to Celsius we need m and b F – F m = 2 1 C2 – C1 212 – 32 m = 100 – 0 180 9 m = = 100 5 9 Therefore F = C + b 5 To find b, substitute the coordinates of either point. 9 32 = (0) + b 5 Therefore b = 32 Therefore the equation is 9 F = C + 32 5 Can you solve for C in terms of F? © 1999, CISC: Curriculum and Instruction Steering Committee The WINNING EQUATION PRIMARY CONTENT MODULE Algebra I -Linear Equations & Inequalities T-74 Celsius in terms of Fahrenheit 9 F = C + 32 5 5 5 9 F = æ C +32ö 9 9è 5 ø 5 5 F = C + (32) 9 9 5 5 F – (32) = C 9 9 5 5 C = F – (32) 9 9 5 C = (F – 32) 9 Example: How many degrees Celsius is77°F? 5 C = (77 – 32) 9 5 C = (45) 9 C = 25° So 72°F = 25°C © 1999, CISC: Curriculum and Instruction Steering Committee The WINNING EQUATION PRIMARY CONTENT MODULE Algebra I -Linear Equations & Inequalities T-75 Standard 8 Algebra I, Grade 8 Standards Students understand the concept of parallel and perpendicular lines and how their slopes are related. -

Form Y-203-I, If You Had More Than One Job, Or If You Had a Job for Only Part of the Year

Department of Taxation and Finance Yonkers Nonresident Earnings Tax Return Y-203 For the full year January 1, 2020, through December 31, 2020, or fiscal year beginning and ending Name as shown on Form IT-201 or IT-203 Social Security number A Were you a Yonkers resident for any part of the taxable year? (mark an X in the appropriate box) Yes No (see instructions) (See the instructions for Form IT-201 or IT-203 for the definition of a resident.) If Yes: 1. Give period of Yonkers residence. From (mmddyyyy) to (mmddyyyy) 2. Are you reporting Yonkers resident income tax surcharge on your New York State return? ..................................................................................... Yes No (submit explanation) 3. You must complete and submit Form IT-360.1 (see instructions). B Did you or your spouse maintain an apartment or other living quarters in Yonkers during any part of the year?...................................................................................... Yes No If Yes, give address below and enter the number of days spent in Yonkers during 2020: days Address: C Are you reporting income from self-employment (on line 2 below)?......... Yes No If Yes, complete the following: Business name Business address Employer identification number Principal business activity Form of business: Sole proprietorship Partnership Other (explain) Calculation of nonresident earnings tax 1 Gross wages and other employee compensation (see instructions; if claiming an allocation, include amount from line 22) ............................................... 1 .00 2 Net earnings from self-employment (see instructions; if claiming an allocation, include amount from line 32; if a loss, write loss on line 2) ............................................................................................... 2 .00 3 Add lines 1 and 2 (if line 2 is a loss, enter amount from line 1) ........................................................... -

A Phenomenological Study of Flourishing in Mid-Career Professionals

Pepperdine University Pepperdine Digital Commons Theses and Dissertations 2020 A phenomenological study of flourishing in mid-career professionals Sohyun Lee [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.pepperdine.edu/etd Part of the Business Commons, Leadership Studies Commons, and the Organization Development Commons Recommended Citation Lee, Sohyun, "A phenomenological study of flourishing in mid-career professionals" (2020). Theses and Dissertations. 1161. https://digitalcommons.pepperdine.edu/etd/1161 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by Pepperdine Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Pepperdine Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected], [email protected]. FLOURISHING IN MID-CAREER PROFESSIONALS Pepperdine University Graduate School of Education and Psychology A PHENOMENOLOGICAL STUDY OF FLOURISHING IN MID-CAREER PROFESSIONALS A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Education in Organizational Leadership by Sohyun Lee July, 2020 Paula Thompson, Ed.D. – Dissertation Chairperson This dissertation, written by Sohyun Lee Under the guidance of a Faculty Committee and approved by its members, has been submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF EDUCATION Doctoral Committee: Paula Thompson, Ed.D., Chairperson Kay Davis, Ed.D Maria -

TPS. 21 and 22 N., R. 11 E. by CLARENCE S. ROSS. INTRODUCTION. the Area Included in Tps. 21 and 22 N., R. 11 E., Lies in The

TPS. 21 AND 22 N., R. 11 E. By CLARENCE S. ROSS. INTRODUCTION. The area included in Tps. 21 and 22 N., R. 11 E., lies in the south eastern part of the Osage Reservation and in the eastern part of the Hominy quadrangle. (See fig. 1.) It may be reached from Skia took and Sperry, on the Midland Valley Railroad, about 4 miles to the east. Two major roads run west from these towns, following the valleys of Hominy and Delaware creeks, but the minor roads are very poor, and much of the area is difficult of access. The entire area is hilly and has a maximum relief of 400 feet. Most of the ridges are timbered, and farming is confined to the alluvial bottoms of the larger creeks. The areal geology of the Hominy quadrangle has been mapped on a scale of 2 miles to the inch in cooperation with the Oklahoma Geological Survey. The detailed structural examination of Tps. 21 and 22 N., R. 11 E., was made in March, April, May, and June, 1918, by the writer, Sidney Powers, W. S. W. Kew, and P. V. Roundy. All the mapping was done with plane table and telescope alidade. STRATIGRAPHY. EXPOSED ROCKS. The rocks exposed at the surface in this area belong to the middle Pennsylvanian, and consist of sandstone, shale, and limestone, ag gregating about 700 feet in thickness. Shale predominates, but sand stone and limestone form the prominent rock exposures. A few of the strata that may be used as key beds will be described for the benefit of those who may wish to do geologic work in the region. -

ISO Basic Latin Alphabet

ISO basic Latin alphabet The ISO basic Latin alphabet is a Latin-script alphabet and consists of two sets of 26 letters, codified in[1] various national and international standards and used widely in international communication. The two sets contain the following 26 letters each:[1][2] ISO basic Latin alphabet Uppercase Latin A B C D E F G H I J K L M N O P Q R S T U V W X Y Z alphabet Lowercase Latin a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z alphabet Contents History Terminology Name for Unicode block that contains all letters Names for the two subsets Names for the letters Timeline for encoding standards Timeline for widely used computer codes supporting the alphabet Representation Usage Alphabets containing the same set of letters Column numbering See also References History By the 1960s it became apparent to thecomputer and telecommunications industries in the First World that a non-proprietary method of encoding characters was needed. The International Organization for Standardization (ISO) encapsulated the Latin script in their (ISO/IEC 646) 7-bit character-encoding standard. To achieve widespread acceptance, this encapsulation was based on popular usage. The standard was based on the already published American Standard Code for Information Interchange, better known as ASCII, which included in the character set the 26 × 2 letters of the English alphabet. Later standards issued by the ISO, for example ISO/IEC 8859 (8-bit character encoding) and ISO/IEC 10646 (Unicode Latin), have continued to define the 26 × 2 letters of the English alphabet as the basic Latin script with extensions to handle other letters in other languages.[1] Terminology Name for Unicode block that contains all letters The Unicode block that contains the alphabet is called "C0 Controls and Basic Latin". -

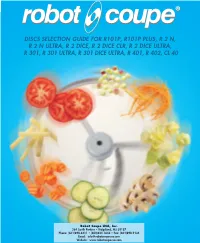

Discs Selection Guide for R101p, R101p Plus, R 2 N, R 2 N Ultra, R 2 Dice, R 2 Dice Clr, R 2 Dice Ultra, R 301, R 301 Ultra

R 301 Dice Ultra, R 402 and CL 40 ONLY Julienne Dicing R 2 Dice, R 2 Dice CLR, R 2 Dice Ultra ONLY R 101P, R 101P Plus, R 2 N, R 2 N CLR, R 2 N Ultra, R 2 Dice, R 2 Dice Ultra, R 301, R 301 Ultra, R 301 Dice Ultra, R 401, R 402 and CL 40 8x8 mm* 10x10 mm* 12x12 mm* (5/16” x 5/16”) (3/8” x 3/8”) (15/32” x 15/32”) Ref. 27113 Ref. 27114 Ref. 27298 Ref. 27264 Ref. 27290 DISCS SELECTION GUIDE FOR R101P, R101P PLUS, R 2 N, 2x2 mm 2x4 mm 2x6 mm Ref. 27265 (5/64” x 5/64”) (5/64” x 5/32”) (5/64” x 1/4”) R 2 N ULTRA, R 2 DICE, R 2 DICE CLR, R 2 DICE ULTRA, Ref. 27599 Ref. 27080 Ref. 27081 R 301, R 301 ULTRA, R 301 DICE ULTRA, R 401, R 402, CL 40 * Use Dice Cleaning Kit to Clean (ref. 39881) French Fries R 301 Dice Ultra, R 402 and CL 40 ONLY 8x8 mm 10x10 mm (5/16” x 5/16”) (3/8” x 3/8”) 4x4 mm 6x6 mm 8x8 mm Ref. 27116 Ref. 27117 (5/32”x 5/32”) (1/4”x 1/4”) (5/16” x 5/16”) Ref. 27047 Ref. 27610 Ref. 27048 Dice Cleaning Kit Reversible grid holder • One side for Smaller Dicing Unit's discs: R 2 Dice, R 301 Dice Ultra, R 402 and CL 40 • One side for Larger Dicing Unit's discs: R 502, R 602 V.V., CL 50, CL 50 Gourmet, CL 51, Cleaning tool CL 52, CL 55 and CL 60 dicing grids Dicing grid cleaning tool 5 mm (3/16”), 8 mm (5/16”) or 10 mm (3/8”) Robot Coupe USA, Inc. -

Ffontiau Cymraeg

This publication is available in other languages and formats on request. Mae'r cyhoeddiad hwn ar gael mewn ieithoedd a fformatau eraill ar gais. [email protected] www.caerphilly.gov.uk/equalities How to type Accented Characters This guidance document has been produced to provide practical help when typing letters or circulars, or when designing posters or flyers so that getting accents on various letters when typing is made easier. The guide should be used alongside the Council’s Guidance on Equalities in Designing and Printing. Please note this is for PCs only and will not work on Macs. Firstly, on your keyboard make sure the Num Lock is switched on, or the codes shown in this document won’t work (this button is found above the numeric keypad on the right of your keyboard). By pressing the ALT key (to the left of the space bar), holding it down and then entering a certain sequence of numbers on the numeric keypad, it's very easy to get almost any accented character you want. For example, to get the letter “ô”, press and hold the ALT key, type in the code 0 2 4 4, then release the ALT key. The number sequences shown from page 3 onwards work in most fonts in order to get an accent over “a, e, i, o, u”, the vowels in the English alphabet. In other languages, for example in French, the letter "c" can be accented and in Spanish, "n" can be accented too. Many other languages have accents on consonants as well as vowels. -

DMV Driver Manual

New Hampshire Driver Manual i 6WDWHRI1HZ+DPSVKLUH DEPARTMENT OF SAFETY DIVISION OF MOTOR VEHICLES MESSAGE FROM THE DIVISION OF MOTOR VEHICLES Driving a motor vehicle on New Hampshire roadways is a privilege and as motorists, we all share the responsibility for safe roadways. Safe drivers and safe vehicles make for safe roadways and we are pleased to provide you with this driver manual to assist you in learning New Hampshire’s motor vehicle laws, rules of the road, and safe driving guidelines, so that you can begin your journey of becoming a safe driver. The information in this manual will not only help you navigate through the process of obtaining a New Hampshire driver license, but it will highlight safe driving tips and techniques that can help prevent accidents and may even save a life. One of your many responsibilities as a driver will include being familiar with the New Hampshire motor vehicle laws. This manual includes a review of the laws, rules and regulations that directly or indirectly affect you as the operator of a motor vehicle. Driving is a task that requires your full attention. As a New Hampshire driver, you should be prepared for changes in the weather and road conditions, which can be a challenge even for an experienced driver. This manual reviews driving emergencies and actions that the driver may take in order to avoid a major collision. No one knows when an emergency situation will arise and your ability to react to a situation depends on your alertness. Many factors, such as impaired vision, fatigue, alcohol or drugs will impact your ability to drive safely. -

Y=Yes, N=No, C=Conditional CODE Mandatory (Y/N/C)* DECODE Description COAF Y to Be Used Here Instead of COAF: ISSUER DISCLOSURE

CODE Mandatory DECODE Description (Y/N/C)* COAF Y To be used here instead This field is used to show the official and of COAF: ISSUER unique identification assigned to a DISCLOSURE REQUEST shareholder’s identification disclosure IDENTIFIER request process by the issuer, or third party nominated by it. DTCM N DATE CALCULATION Indicates the logical method to be used to METHOD determine and communicate from which date the shares have been held. The two possible values are LIFO and FIFO. For further guidance please refer to the Market Standards for Shareholder Identification. FWRI N FORWARD REQUEST TO Indicates whether the request is to be NEXT INTERMEDIARY forwarded to and responded by intermediaries down the chain of intermediaries. If to be forwarded, the indicator (Y) is added. If not to be forwarded, the indicator will either be (N) or not be present. INFO N ADDITIONAL Any additional information will be stated INFORMATION here. INME N ISSUER NAME Name of Issuer of the ISIN ISDD Y ISSUER DISCLOSURE Latest date/time set by the issuer, or a DEADLINE third party appointed by the issuer, at which the response to the request to disclose shareholder identity shall be provided by each intermediary to the Response Recipient. RADR C ADDRESS OF RECIPIENT Address of the party to which the disclosure response must be sent. RADT N ADDRESS TYPE OF Address type to be used for the Response RECIPIENT Recipient, e.g. BIC, Email or URL RBIC C BIC OF RECEPIENT BIC of Response Recipient REML C EMAIL ID OF RECEPIENT Email Address of Response Recipient RLEI N LEI OF RECEPIENT Legal Entity Identifier of Response Recipient RNME N RECEPIENT NAME Name of Response Recipient RTCI N RESPONSE THROUGH Indicates whether the shareholder CHAIN OF identification disclosure response is to be INTERMEDIARIES sent back up the chain of intermediaries or directly to the determined Response Recipient. -

QSO-21-19-NH DATE: May 11, 2021

DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH & HUMAN SERVICES Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services 7500 Security Boulevard, Mail Stop C2-21-16 Baltimore, Maryland 21244-1850 Center for Clinical Standards and Quality/Quality, Safety & Oversight Group Ref: QSO-21-19-NH DATE: May 11, 2021 TO: State Survey Agency Directors FROM: Director Quality, Safety & Oversight Group SUBJECT: Interim Final Rule - COVID-19 Vaccine Immunization Requirements for Residents and Staff Memorandum Summary • CMS is committed to continually taking critical steps to ensure America’s healthcare facilities continue to respond effectively to the Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) Public Health Emergency (PHE). • On May 11, 2021, CMS published an interim final rule with comment period (IFC). This rule establishes Long-Term Care (LTC) Facility Vaccine Immunization Requirements for Residents and Staff. This includes new requirements for educating residents or resident representatives and staff regarding the benefits and potential side effects associated with the COVID-19 vaccine, and offering the vaccine. Furthermore, LTC facilities must report COVID-19 vaccine and therapeutics treatment information to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s (CDC) National Healthcare Safety Network (NHSN). • Transparency: CMS will post the new information reported to the NHSN for viewing by facilities, stakeholders, or the general public on CMS’s COVID-19 Nursing Home Data website. • Updated Survey Tools: CMS has updated tools used by surveyors to assess compliance with these new requirements. Background On December 1, 2020, the Advisory Committee in Immunization Practices (ACIP) recommended that health care personnel (HCP) and long-term care (LTC) facility residents be offered COVID-19 vaccination first (Phase 1a).1 Ensuring LTC residents receive COVID-19 vaccinations will help protect those who are most at risk of severe infection or death from COVID-19.