Cardinality Finite Sets Given a Natural Number N ∈ N

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Algebra I Chapter 1. Basic Facts from Set Theory 1.1 Glossary of Abbreviations

Notes: c F.P. Greenleaf, 2000-2014 v43-s14sets.tex (version 1/1/2014) Algebra I Chapter 1. Basic Facts from Set Theory 1.1 Glossary of abbreviations. Below we list some standard math symbols that will be used as shorthand abbreviations throughout this course. means “for all; for every” • ∀ means “there exists (at least one)” • ∃ ! means “there exists exactly one” • ∃ s.t. means “such that” • = means “implies” • ⇒ means “if and only if” • ⇐⇒ x A means “the point x belongs to a set A;” x / A means “x is not in A” • ∈ ∈ N denotes the set of natural numbers (counting numbers) 1, 2, 3, • · · · Z denotes the set of all integers (positive, negative or zero) • Q denotes the set of rational numbers • R denotes the set of real numbers • C denotes the set of complex numbers • x A : P (x) If A is a set, this denotes the subset of elements x in A such that •statement { ∈ P (x)} is true. As examples of the last notation for specifying subsets: x R : x2 +1 2 = ( , 1] [1, ) { ∈ ≥ } −∞ − ∪ ∞ x R : x2 +1=0 = { ∈ } ∅ z C : z2 +1=0 = +i, i where i = √ 1 { ∈ } { − } − 1.2 Basic facts from set theory. Next we review the basic definitions and notations of set theory, which will be used throughout our discussions of algebra. denotes the empty set, the set with nothing in it • ∅ x A means that the point x belongs to a set A, or that x is an element of A. • ∈ A B means A is a subset of B – i.e. -

COMPSCI 501: Formal Language Theory Insights on Computability Turing Machines Are a Model of Computation Two (No Longer) Surpris

Insights on Computability Turing machines are a model of computation COMPSCI 501: Formal Language Theory Lecture 11: Turing Machines Two (no longer) surprising facts: Marius Minea Although simple, can describe everything [email protected] a (real) computer can do. University of Massachusetts Amherst Although computers are powerful, not everything is computable! Plus: “play” / program with Turing machines! 13 February 2019 Why should we formally define computation? Must indeed an algorithm exist? Back to 1900: David Hilbert’s 23 open problems Increasingly a realization that sometimes this may not be the case. Tenth problem: “Occasionally it happens that we seek the solution under insufficient Given a Diophantine equation with any number of un- hypotheses or in an incorrect sense, and for this reason do not succeed. known quantities and with rational integral numerical The problem then arises: to show the impossibility of the solution under coefficients: To devise a process according to which the given hypotheses or in the sense contemplated.” it can be determined in a finite number of operations Hilbert, 1900 whether the equation is solvable in rational integers. This asks, in effect, for an algorithm. Hilbert’s Entscheidungsproblem (1928): Is there an algorithm that And “to devise” suggests there should be one. decides whether a statement in first-order logic is valid? Church and Turing A Turing machine, informally Church and Turing both showed in 1936 that a solution to the Entscheidungsproblem is impossible for the theory of arithmetic. control To make and prove such a statement, one needs to define computability. In a recent paper Alonzo Church has introduced an idea of “effective calculability”, read/write head which is equivalent to my “computability”, but is very differently defined. -

MATH 361 Homework 9

MATH 361 Homework 9 Royden 3.3.9 First, we show that for any subset E of the real numbers, Ec + y = (E + y)c (translating the complement is equivalent to the complement of the translated set). Without loss of generality, assume E can be written as c an open interval (e1; e2), so that E + y is represented by the set fxjx 2 (−∞; e1 + y) [ (e2 + y; +1)g. This c is equal to the set fxjx2 = (e1 + y; e2 + y)g, which is equivalent to the set (E + y) . Second, Let B = A − y. From Homework 8, we know that outer measure is invariant under translations. Using this along with the fact that E is measurable: m∗(A) = m∗(B) = m∗(B \ E) + m∗(B \ Ec) = m∗((B \ E) + y) + m∗((B \ Ec) + y) = m∗(((A − y) \ E) + y) + m∗(((A − y) \ Ec) + y) = m∗(A \ (E + y)) + m∗(A \ (Ec + y)) = m∗(A \ (E + y)) + m∗(A \ (E + y)c) The last line follows from Ec + y = (E + y)c. Royden 3.3.10 First, since E1;E2 2 M and M is a σ-algebra, E1 [ E2;E1 \ E2 2 M. By the measurability of E1 and E2: ∗ ∗ ∗ c m (E1) = m (E1 \ E2) + m (E1 \ E2) ∗ ∗ ∗ c m (E2) = m (E2 \ E1) + m (E2 \ E1) ∗ ∗ ∗ ∗ c ∗ c m (E1) + m (E2) = 2m (E1 \ E2) + m (E1 \ E2) + m (E1 \ E2) ∗ ∗ ∗ c ∗ c = m (E1 \ E2) + [m (E1 \ E2) + m (E1 \ E2) + m (E1 \ E2)] c c Second, E1 \ E2, E1 \ E2, and E1 \ E2 are disjoint sets whose union is equal to E1 [ E2. -

Solutions to Homework 2 Math 55B

Solutions to Homework 2 Math 55b 1. Give an example of a subset A ⊂ R such that, by repeatedly taking closures and complements. Take A := (−5; −4)−Q [[−4; −3][f2g[[−1; 0][(1; 2)[(2; 3)[ (4; 5)\Q . (The number of intervals in this sets is unnecessarily large, but, as Kevin suggested, taking a set that is complement-symmetric about 0 cuts down the verification in half. Note that this set is the union of f0g[(1; 2)[(2; 3)[ ([4; 5] \ Q) and the complement of the reflection of this set about the the origin). Because of this symmetry, we only need to verify that the closure- complement-closure sequence of the set f0g [ (1; 2) [ (2; 3) [ (4; 5) \ Q consists of seven distinct sets. Here are the (first) seven members of this sequence; from the eighth member the sets start repeating period- ically: f0g [ (1; 2) [ (2; 3) [ (4; 5) \ Q ; f0g [ [1; 3] [ [4; 5]; (−∞; 0) [ (0; 1) [ (3; 4) [ (5; 1); (−∞; 1] [ [3; 4] [ [5; 1); (1; 3) [ (4; 5); [1; 3] [ [4; 5]; (−∞; 1) [ (3; 4) [ (5; 1). Thus, by symmetry, both the closure- complement-closure and complement-closure-complement sequences of A consist of seven distinct sets, and hence there is a total of 14 different sets obtained from A by taking closures and complements. Remark. That 14 is the maximal possible number of sets obtainable for any metric space is the Kuratowski complement-closure problem. This is proved by noting that, denoting respectively the closure and com- plement operators by a and b and by e the identity operator, the relations a2 = a; b2 = e, and aba = abababa take place, and then one can simply list all 14 elements of the monoid ha; b j a2 = a; b2 = e; aba = abababai. -

Axiomatic Set Teory P.D.Welch

Axiomatic Set Teory P.D.Welch. August 16, 2020 Contents Page 1 Axioms and Formal Systems 1 1.1 Introduction 1 1.2 Preliminaries: axioms and formal systems. 3 1.2.1 The formal language of ZF set theory; terms 4 1.2.2 The Zermelo-Fraenkel Axioms 7 1.3 Transfinite Recursion 9 1.4 Relativisation of terms and formulae 11 2 Initial segments of the Universe 17 2.1 Singular ordinals: cofinality 17 2.1.1 Cofinality 17 2.1.2 Normal Functions and closed and unbounded classes 19 2.1.3 Stationary Sets 22 2.2 Some further cardinal arithmetic 24 2.3 Transitive Models 25 2.4 The H sets 27 2.4.1 H - the hereditarily finite sets 28 2.4.2 H - the hereditarily countable sets 29 2.5 The Montague-Levy Reflection theorem 30 2.5.1 Absoluteness 30 2.5.2 Reflection Theorems 32 2.6 Inaccessible Cardinals 34 2.6.1 Inaccessible cardinals 35 2.6.2 A menagerie of other large cardinals 36 3 Formalising semantics within ZF 39 3.1 Definite terms and formulae 39 3.1.1 The non-finite axiomatisability of ZF 44 3.2 Formalising syntax 45 3.3 Formalising the satisfaction relation 46 3.4 Formalising definability: the function Def. 47 3.5 More on correctness and consistency 48 ii iii 3.5.1 Incompleteness and Consistency Arguments 50 4 The Constructible Hierarchy 53 4.1 The L -hierarchy 53 4.2 The Axiom of Choice in L 56 4.3 The Axiom of Constructibility 57 4.4 The Generalised Continuum Hypothesis in L. -

ON the CONSTRUCTION of NEW TOPOLOGICAL SPACES from EXISTING ONES Consider a Function F

ON THE CONSTRUCTION OF NEW TOPOLOGICAL SPACES FROM EXISTING ONES EMILY RIEHL Abstract. In this note, we introduce a guiding principle to define topologies for a wide variety of spaces built from existing topological spaces. The topolo- gies so-constructed will have a universal property taking one of two forms. If the topology is the coarsest so that a certain condition holds, we will give an elementary characterization of all continuous functions taking values in this new space. Alternatively, if the topology is the finest so that a certain condi- tion holds, we will characterize all continuous functions whose domain is the new space. Consider a function f : X ! Y between a pair of sets. If Y is a topological space, we could define a topology on X by asking that it is the coarsest topology so that f is continuous. (The finest topology making f continuous is the discrete topology.) Explicitly, a subbasis of open sets of X is given by the preimages of open sets of Y . With this definition, a function W ! X, where W is some other space, is continuous if and only if the composite function W ! Y is continuous. On the other hand, if X is assumed to be a topological space, we could define a topology on Y by asking that it is the finest topology so that f is continuous. (The coarsest topology making f continuous is the indiscrete topology.) Explicitly, a subset of Y is open if and only if its preimage in X is open. With this definition, a function Y ! Z, where Z is some other space, is continuous if and only if the composite function X ! Z is continuous. -

MAD FAMILIES CONSTRUCTED from PERFECT ALMOST DISJOINT FAMILIES §1. Introduction. a Family a of Infinite Subsets of Ω Is Called

The Journal of Symbolic Logic Volume 00, Number 0, XXX 0000 MAD FAMILIES CONSTRUCTED FROM PERFECT ALMOST DISJOINT FAMILIES JORG¨ BRENDLE AND YURII KHOMSKII 1 Abstract. We prove the consistency of b > @1 together with the existence of a Π1- definable mad family, answering a question posed by Friedman and Zdomskyy in [7, Ques- tion 16]. For the proof we construct a mad family in L which is an @1-union of perfect a.d. sets, such that this union remains mad in the iterated Hechler extension. The construction also leads us to isolate a new cardinal invariant, the Borel almost-disjointness number aB , defined as the least number of Borel a.d. sets whose union is a mad family. Our proof yields the consistency of aB < b (and hence, aB < a). x1. Introduction. A family A of infinite subsets of ! is called almost disjoint (a.d.) if any two elements a; b of A have finite intersection. A family A is called maximal almost disjoint, or mad, if it is an infinite a.d. family which is maximal with respect to that property|in other words, 8a 9b 2 A (ja \ bj = !). The starting point of this paper is the following theorem of Adrian Mathias [11, Corollary 4.7]: Theorem 1.1 (Mathias). There are no analytic mad families. 1 On the other hand, it is easy to see that in L there is a Σ2 definable mad family. In [12, Theorem 8.23], Arnold Miller used a sophisticated method to 1 prove the seemingly stronger result that in L there is a Π1 definable mad family. -

Algorithms, Turing Machines and Algorithmic Undecidability

U.U.D.M. Project Report 2021:7 Algorithms, Turing machines and algorithmic undecidability Agnes Davidsdottir Examensarbete i matematik, 15 hp Handledare: Vera Koponen Examinator: Martin Herschend April 2021 Department of Mathematics Uppsala University Contents 1 Introduction 1 1.1 Algorithms . .1 1.2 Formalisation of the concept of algorithms . .1 2 Turing machines 3 2.1 Coding of machines . .4 2.2 Unbounded and bounded machines . .6 2.3 Binary sequences representing real numbers . .6 2.4 Examples of Turing machines . .7 3 Undecidability 9 i 1 Introduction This paper is about Alan Turing's paper On Computable Numbers, with an Application to the Entscheidungsproblem, which was published in 1936. In his paper, he introduced what later has been called Turing machines as well as a few examples of undecidable problems. A few of these will be brought up here along with Turing's arguments in the proofs but using a more modern terminology. To begin with, there will be some background on the history of why this breakthrough happened at that given time. 1.1 Algorithms The concept of an algorithm has always existed within the world of mathematics. It refers to a process meant to solve a problem in a certain number of steps. It is often repetitive, with only a few rules to follow. In more recent years, the term also has been used to refer to the rules a computer follows to operate in a certain way. Thereby, an algorithm can be used in a plethora of circumstances. The word might describe anything from the process of solving a Rubik's cube to how search engines like Google work [4]. -

Cardinality of Wellordered Disjoint Unions of Quotients of Smooth Equivalence Relations on R with All Classes Countable Is the Main Result of the Paper

CARDINALITY OF WELLORDERED DISJOINT UNIONS OF QUOTIENTS OF SMOOTH EQUIVALENCE RELATIONS WILLIAM CHAN AND STEPHEN JACKSON Abstract. Assume ZF + AD+ + V = L(P(R)). Let ≈ denote the relation of being in bijection. Let κ ∈ ON and hEα : α<κi be a sequence of equivalence relations on R with all classes countable and for all α<κ, R R R R R /Eα ≈ . Then the disjoint union Fα<κ /Eα is in bijection with × κ and Fα<κ /Eα has the J´onsson property. + <ω Assume ZF + AD + V = L(P(R)). A set X ⊆ [ω1] 1 has a sequence hEα : α<ω1i of equivalence relations on R such that R/Eα ≈ R and X ≈ F R/Eα if and only if R ⊔ ω1 injects into X. α<ω1 ω ω Assume AD. Suppose R ⊆ [ω1] × R is a relation such that for all f ∈ [ω1] , Rf = {x ∈ R : R(f,x)} ω is nonempty and countable. Then there is an uncountable X ⊆ ω1 and function Φ : [X] → R which uniformizes R on [X]ω: that is, for all f ∈ [X]ω, R(f, Φ(f)). Under AD, if κ is an ordinal and hEα : α<κi is a sequence of equivalence relations on R with all classes ω R countable, then [ω1] does not inject into Fα<κ /Eα. 1. Introduction The original motivation for this work comes from the study of a simple combinatorial property of sets using only definable methods. The combinatorial property of concern is the J´onsson property: Let X be any n n <ω n set. -

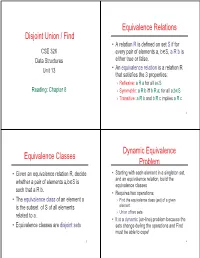

Disjoint Union / Find Equivalence Relations Equivalence Classes

Equivalence Relations Disjoint Union / Find • A relation R is defined on set S if for CSE 326 every pair of elements a, b∈S, a R b is Data Structures either true or false. Unit 13 • An equivalence relation is a relation R that satisfies the 3 properties: › Reflexive: a R a for all a∈S Reading: Chapter 8 › Symmetric: a R b iff b R a; for all a,b∈S › Transitive: a R b and b R c implies a R c 2 Dynamic Equivalence Equivalence Classes Problem • Given an equivalence relation R, decide • Starting with each element in a singleton set, whether a pair of elements a,b∈S is and an equivalence relation, build the equivalence classes such that a R b. • Requires two operations: • The equivalence class of an element a › Find the equivalence class (set) of a given is the subset of S of all elements element › Union of two sets related to a. • It is a dynamic (on-line) problem because the • Equivalence classes are disjoint sets sets change during the operations and Find must be able to cope! 3 4 Disjoint Union - Find Union • Maintain a set of disjoint sets. • Union(x,y) – take the union of two sets › {3,5,7} , {4,2,8}, {9}, {1,6} named x and y • Each set has a unique name, one of its › {3,5,7} , {4,2,8}, {9}, {1,6} members › Union(5,1) › {3,5,7} , {4,2,8}, {9}, {1,6} {3,5,7,1,6}, {4,2,8}, {9}, 5 6 Find An Application • Find(x) – return the name of the set • Build a random maze by erasing edges. -

Handout #4: Connected Metric Spaces

Connected Sets Math 331, Handout #4 You probably have some intuitive idea of what it means for a metric space to be \connected." For example, the real number line, R, seems to be connected, but if you remove a point from it, it becomes \disconnected." However, it is not really clear how to define connected metric spaces in general. Furthermore, we want to say what it means for a subset of a metric space to be connected, and that will require us to look more closely at subsets of metric spaces than we have so far. We start with a definition of connected metric space. Note that, similarly to compactness and continuity, connectedness is actually a topological property rather than a metric property, since it can be defined entirely in terms of open sets. Definition 1. Let (M; d) be a metric space. We say that (M; d) is a connected metric space if and only if M cannot be written as a disjoint union N = X [ Y where X and Y are both non-empty open subsets of M. (\Disjoint union" means that M = X [ Y and X \ Y = ?.) A metric space that is not connected is said to be disconnnected. Theorem 1. A metric space (M; d) is connected if and only if the only subsets of M that are both open and closed are M and ?. Equivalently, (M; d) is disconnected if and only if it has a non-empty, proper subset that is both open and closed. Proof. Suppose (M; d) is a connected metric space. -

Real Analysis 1 Math 623 Notes by Patrick Lei, May 2020

Real Analysis 1 Math 623 Notes by Patrick Lei, May 2020 Lectures by Robin Young, Fall 2018 University of Massachusetts, Amherst Disclaimer These notes are a May 2020 transcription of handwritten notes taken during lecture in Fall 2018. Any errors are mine and not the instructor’s. In addition, my notes are picture-free (but will include commutative diagrams) and are a mix of my mathematical style (omit lengthy computations, use category theory) and that of the instructor. If you find any errors, please contact me at [email protected]. Contents Contents • 2 1 Lebesgue Measure • 3 1.1 Motivation for the Course • 3 1.2 Basic Notions • 4 1.3 Rectangles • 5 1.4 Outer Measure • 6 1.5 Measurable Sets • 7 1.6 Measurable Functions • 10 2 Integration • 13 2.1 Defining the Integral • 13 2.2 Some Convergence Results • 15 2.3 Vector Space of Integrable Functions • 16 2.4 Symmetries • 18 3 Differentiation • 20 3.1 Integration and Differentiation • 20 3.2 Kernels • 22 3.3 Differentiation • 26 3.4 Bounded Variation • 28 3.5 Absolute Continuity • 30 4 General Measures • 33 4.1 Outer Measures • 34 4.2 Results and Applications • 35 4.3 Signed Measures • 36 2 1 Lebesgue Measure 1.1 Motivation for the Course We will consider some examples that show us some fundamental problems in analysis. Example 1.1 (Fourier Series). Let f be periodic on [0, 2π]. Then if f is sufficiently nice, we can write inx f(x) = ane , n X 1 2π inx where an = 2π 0 f(x)e dx.