Meat Gluttons of Western Mexico

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Presentación De Powerpoint

RECETAS PARA ESTE 15 DE SEPTIEMBRE Pozole Pozole sazonado con chile guajillo para aportar color e intensificar el sabor de la preparación, con pollo deshebrado, acompañado de la clásica guarnición de rábano, orégano, cebolla morada y láminas de aguacate, servido con aire de limón que ayuda a redondear el sabor. Tipo de receta Estándar Rendimiento 3.700 Kg Tamaño de la porción 0.37 Kg No. de porciones 10 Tiempo de preparación 20 minutos Tiempo de cocción 40 minutos Clasificación (tiempo/segmento) Plato fuerte PRODUCTO UFS: Knorr® Caldo de Pollo INGREDIENTES CANTIDAD UNIDAD Para el caldo: Pechuga de pollo con hueso 1.000 Kg Agua 3.000 L Knorr® Caldo de Pollo 0.035 Kg Laurel 0.002 Kg Chile guajillo molido 0.200 L Aceite 0.030 Kg Para la guarnición: Maíz pozolero cocido 0.500 Rábano en rodajas Kg Orégano seco 0.050 Kg Cebolla morada picada 0.001 Kg Láminas de aguacate 0.020 Kg Lechuga fileteada 0.050 Kg finamente 0.050 Kg Para el aire de limón: Jugo de limón 0.050 L Lecitina de soya 0.000 Kg MODO DE ELABORACIÓN: Paso 1.- Para el caldo: Cocer el pollo en el agua con el laurel y Knorr® Caldo de pollo. Paso 2.- Colar el caldo y desmenuzar el pollo. Calentar el aceite y freír el guajillo, agregar el caldo y el maíz pozolero, hervir por 5 minutos y rectificar sazón. Paso 3.- Para la guarnición: En un plato hondo colocar con ayuda de un cortador, montar el maíz pozolero seguido del pollo deshebrado, colocar la lechuga, los rábanos, el orégano seco y las láminas de aguacate. -

Me Gusta Menu

Combination Plates Cheeseburger Combo $5.00 Serve with Rice, Beans, Tortillas & Salsa With Fries and Can Soda Combo #1 - Taco Combo $5.50 (2 Tacos) Two tacos, Asada, Chicken, Ordenes Extrasl Side Order Shrimp, Carnitas French Fries /Papas Fritas $1.99 Combo #2 - Tamale Plate $6.99 Rice / Arroz $1.50 Combo One Tamale, Two Tacos Beans / Frijoles $1.50 Avocado / Aguacate $0.75 Combo #3 - Chile Relleno $8.99 Sour cream / Crema $0.50 2 Tacos, Chile Relleno, Two Tacos Extra Cheese / Extra Queso $0.75 Combo #4 - 2 Chiles $8.99 Chips & Salsa $2.00 Rellenos Two Chile Rellenos, Rice & Beans Combo #5 - Chile relleno -$7.99 Tamal Beverages I Bebidas Combo #6 - 2 Tamales $6.99 ':.~ c1 aroz y frijoles (two Tamale Rice and beans Coffee $1.50 Jarritos $1.50 Family Pack #1 Snapples $1.75 Orange Juice $1.75 10 Tacos I 5 Tamales $2499 Coke 20 oz $1.75 Fresh Lemonade i- __ ~-.. $2.00 & 2 Liter Coke Horchata/Jamaica $2.00 Family Pack #2 Lancaster 518 W. Lancaster Blvd. 15 Tacos, Rice, Lancaster, CA. 9534 Beans, Salsa & $2499 2 Liter coke (661) 945-4101 Me Gusta Family Pack # 1 Lancaster Market Place Carnitas 1_5 pound $1599 44830 Valley Central Way #114 Rice, Beans, Salsa Lancaster, CA. 93536 Tortilas & 2 Liter coke (661)948-9111 Me Gusta Family Pack # 2 VISA'_ Ú-kMY _. 6 Tacos, 3 Tamales Chips, Salsa & $1599 We Accept Visa, Master Card, Debit, American express, 2 Liter coke Discovery, JCB (Taxes are not included) Desayuno/Breakfast $5.95 Quesadillas Me Gusta $6.99 Serve with Rice,Beans & Tortilas GflURllXT T:lflJllES Another Specialty Made with Mozzarela Cheese, Huevos Rancheros/Mexican Eggs '..--: Our Specialty ~ Bell Pepper, Onion & mushrooms. -

GUACAMOLE with Tostadas, Lime ...Mkt CHILE CON QUESO Classic

GUACAMOLE with tostadas, lime ............................. Mkt FLAUTAS crispy chicken tacos, lettuce, guacamole, sour cream, queso fresco ....................................... 13 CHILE CON QUESO Classic .................................................................... 7 NACHOS bean and cheese nachos, jalapeños, Picadillo ................................................................... 9 guacamole, sour cream .......................................... 10 Chicken Fajita .......................................................... 9 Compuesto (picadillo, guacamole & sour cream) ..................... 12 CHICKEN FAJITA NACHOS grilled chicken on bean and cheese nachos, jalapeños, guacamole, QUESO FUNDIDO sour cream ............................................................ 14 Broiled Monterey Jack and Chihuahua cheeses, warm tortillas, salsa cremosa ........................................... 10 STEAK FAJITA NACHOS* grilled steak on bean and ~ con rajas y hongos .............................................. 12 cheese nachos, jalapeños, guac., sour cream ........... 16 ~ con chorizo ......................................................... 13 chili gravy and ~ con camarones ................................................... 13 DELTA STYLE HOT TAMALES saltine crackers…messy but worth it! ................................ 12 CAMPECHANA DE MARISCOS 16 Mexican “cocktail” of spicy gulf shrimp, octopus, lump crab and avocado, tostadas “AGUA CHILE” TOSTADA* 16 gulf shrimp and snapper ceviche, smoked jalapeño salsa, cilantro & radish ENSALADA -

Free Delivery Chilaquiles Con Bistek

APPETIZERS CHILANGOS SAMPLER ................................ 9.75 2 Mini Cheese Quesadilla FREE 2 Mini Chicken Flautas 1 Tostada with Beans & Cheese NACHOS CHILANGOS .................................. 9.75 DELIVERY Choice of Meat Refried Beans, Mozzarella Cheese ON ORDERS OVER $20 Sour Cream, Pico De Gallo & Guacamole CHORIQUESO CHILANGOS ......................... 6.75 Mexican Chorizo (Ground Sausage Meat) with Mozzarella Cheese, Pico De Gallo, Flour Tortillas GUACAMOLE CHILANGOS .......................... 4.50 Mashed Avocado and Pico De Gallo BOQUITA PLATE .......................................... 12.75 Beef, Fresh Cheese, Wiener Rolls, 2 Shrimp To-Go Menu & Chicken Flautas QUESO DIP .................................................... 4.75 BREAKFAST 2633 Williams Blvd. Kenner, La 70062 HUEVOS RANCHEROS ................................. 7.75 Two Eggs on Two Tostadas Topped with Ranchero Sauce, and Beans (504) 469-5599 HUEVOS DIVORCIADOS .............................. 7.75 Two Eggs Covered with Green & Red Sauce, Beans and Tortillas www.chilangosnola.com HUEVOS A LA MEXICANA .......................... 7.75 Scramble Eggs with Tomatoes, Onions and Pepper, Cream, Beans and Tortillas FREE DELIVERY CHILAQUILES CON BISTEK ........................ 12.75 ON ORDERS OVER $20 Fried Tortillas Topped with Tomatillo Sauce, Cheese, Egg on Top Tosted Bread, & Beans. HUEVOS RANCHEROS CON BISTEK .......... 12.75 Two Eggs on Two Tostadas, Topped With Ranchero Sauce, Beans Avocado & Fresh Cheese CENA CAMPESINA ...................................... 12.75 -

Dinner Menu 0CT24 Copy

Order from the Bar or in the Dining Area AVAILABLE IN THE DINING ROOM AVAILABLE IN THE DINING ROOM All dishes meant to be shared and come from the kitchen as ready All dishes meant to be shared and come from the kitchen as ready BOTANAS ANTOJITOS PLATOS FUERTES larger plates to share snacks bites to share Ensalada de CeaSAR 10 BIRRIA DE RES 25 GUACAMOLE & TOTOPOS | w CHICHARRONES 11 | 14 salad of little gem, kale, chioggia beet, quinoa, queso gouda, Beef birria braised in chile ancho adobo, red rice, avocado, CACAHUATES 8 avocado, cashew caesar dressing pickled onion, salsa milagros, corn tortillas pickled peanuts, carrot, jicama, jalapeño, chile spice aguachile 18 CALDO MICHI 20 lime marinated white fish, chile de árbol, kohlrabi Black cod, fall vegetables, chile morita & chile de árbol, VEGETALES EN ESCABECHE DE TEMPORADA 8 escabeche, jicama, radish, onion, papalo oil, sesame togarashi with crispy potato tacos pickled potatoes, beets, baby carrots, kafir crema SOPA DE RANCHO 9 Enmoladas de pollo 20 GARBANZO FRITO 4 chicken soup, yukon potato, chayote squash, carrot, A la plancha grilled chicken enchiladas in poblano mole, cauliflower, rice, avocado, chile de árbol flakes salted crispy chickpeas, chile spice rice, treviso, avocado, queso cotija, kafir crema Flauta de pollo 13 *contains nuts and gluten crispy rolled corn tortilla “flute” of pulled chicken in chile guajillo adobo, cabbage, queso cotija, kafir crema, salsa tatemada desayuno “Tacos” @ the BAr Tamal de calabaza con rajas 13 brunch items available Saturday & Sunday 11am-3pm -

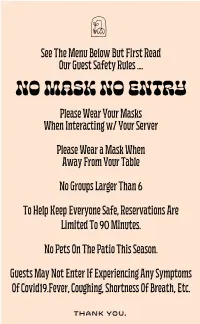

See the Menu Below but First Read Our Guest Safety Rules

See The Menu Below But First Read Our Guest Safety Rules .... NO MASK NO ENTRY Please Wear Your Masks When Interacting w/ Your Server Please Wear a Mask When Away From Your Table No Groups Larger Than 6 To Help Keep Everyone Safe, Reservations Are Limited To 90 Minutes. No Pets On The Patio This Season. Guests May Not Enter If Experiencing Any Symptoms Of Covid19.Fever, Coughing, Shortness Of Breath, Etc. THANK YOU. OME NES ROS LO E CLASSICS CHIPS & SALSAS (V)..................................$3 Tomatillo Crudo & Pineapple Habanero CHILE CON QUESO (V).................................$8 Poblano, Tomato, Cilantro + Black Beans & Chorizo (‡) ......................$2.5 FRANKIE’S VEGAN QUESO .............................$8 Coconut Milk, Potato, Carrot, Nutritional Yeast, Poblano, Tomato, Cilantro(VEGAN) TRUCK STOP NACHOS(V)..............................$10 Black Beans, Queso, Pickled Red Onion, Pickled Jalapeño, Pickled Banana Pepper, Crema + Picadillo Beef, Chorizo, or Beef Suadero ........$3 VEGAN NACHOS ......................................$10 Black Bean, Vegan Queso, Pickled Red Onion, Pickled Banana Peppers, Pickled Jalapenos, Vegan Crema(VEGAN) GUACAMOLE(V) .......................................$8 Red Onion, Jalapeño, Cilantro, Lime GRILLED CHEESE QUESADILLA (V) ......................$4 Chihuahua,Oaxaca EMPANADAS .........................................$10 Cheesesteak, Salsa Doña *LIMITED AVAILABILITY* We’ve added $2 to our empanadas to raise money for the #DoughSomething campaign — a group of restaurants coming together in solidarity -

View Detailed Menu

BIG BURRITOS $8.29 (+tax) TORTAS $8.29(+tax) $3.19(+tax) Big flour tortilla filled with rice, beans, topped French bread filled with your choice of meat BURGERS All burgers include lettuce, tomatoes, + mayonnaise, sour cream, tomatoes, lettuce, with onions and cilantro + your choice of the mayonnaise, onions & pickles one of the following meats: onions, pepper and Jack Monterey cheese. 1. Asada (Beef) 1. Asada (Beef) COMBOS - include reg. Fries & med drink 2. Adobada (Marinated Pork) 2. Adobada (Marinated Pork) COMBO # 1 3. Pollo (Chicken) 3. Pollo (Chicken) Double Burger - $7.19 + tax 4. Carnitas (Fried Pork) 4. Carnitas (Fried Pork) 5. Chuleta (Pork Chop) COMBO # 2 5. Chuleta (Pork Chop) Cheese Burger - $6.19 + tax 6. Chorizo (Mexican Sausage) $8.79 + tax 6. Chorizo (Mexican Sausage) 7. Lengua (Beef Tongue) - $8.79 + tax $3.49 COMBO # 3 Hamburger - $5.79 + tax 8. Lomito (Pork Butt) 7. Lengua (Beef Tongue) - $8.79 + tax 9. Rajas (Strips of Pasilla Pepper) 8. Lomito (Pork Butt) KID COMBO 10. Choriquezo (Chorizo w/ Cheese) 9. Rajas (Strips of Pasilla Pepper) $3.49 includes Hamburger w/ lettuce and meat only, regular fries and small drink - $4.54 + tax 11. Chile Verde (Green Salsa Pork) 10. Chile Verde (Green Salsa Pork) 12. Vegetarian (zuchinni, lettuce, tomato, pasilla and 11. Vegetarian (zuchinni, lettuce, tomato, pasilla bell pepper and cheese) HAMBURGER - $2.99 +tax and bell pepper and cheese) CHEESEBURGER - $3.49 +tax 13. Chile Relleno (Sutffed Pasilla Pepper) $8.79 + tax 12. Jamon - Ham DOUBLE CHEESE - $4.45 +tax 14. Quezo - Cheese - $4.45 + tax (add ons: avocado: + 0.75, sour cream: + 0.50, 15. -

Corona • Bohemia • Dos Equis (Lager & Amber)

• BUDWEISER • CORONA • BUD LIGHT • BOHEMIA • COORS LIGHT • DOS EQUIS (LAGER & AMBER) • MILLLER LITE • MODELO • MICHELOB ULTRA • NEGRA MODELO • MODELO ESPECIAL • PACIFICO • TECATE • LIME MARGARITA • HEINEKEN • STRAWBERRY MARGARITA • VICTORIA • TAMARIND MARGARITA • ESTRELLA • MANGONEADA MARGARITA • PIÑA COLADA COCKTAILS • MICHELADA • LIME MARGARITA • PIÑA COLADA • STRAWBERY MARGARITA BOTTLE OR SHOTS • EL GUITARRON • EL JINETE BLANCO WINES • WHITE ZINFANDEL • MOSCATO • CHARDONNAY • STELLA ROSA • MERLOT CHORIQUESO (With tortillas) . 8 .25 3 TAQUITOS (With guacamole) . 10 .25 3 TACOS DE PAPAS . 6. .99. ONE CHIMICHANGA . 10 . .99 Fried burrito with guacamole & sour cream on top CHEESE QUESADILLA . 8 .99 . MEAT QUESADILLA . 10 .99 MEXICAN QUESADILLA . 11 . .50 Asada or choice of meat cooked with onions, tomato, bell pepper. Garnished with lettuce, sour cream, and guacamole REGULAR NACHOS . 8. .99. Beans, cheese and home sauce SUPER NACHOS . 12 . .25 Beans, cheese, home sauce and your choice of meat. Topped with guacamole and sour cream SHRIMP NACHOS . 14. .25 Beans, cheese, home sauce and shrimp. Topped with guacamole and sour cream CARNE ASADA FRIES . 12 .25 PARA UNA PERSONA . 22 .99 PARA DOS . 34. .99 All Combinations served with rice and beans. Upgrade soft taco to hard shell $1ea #1 ONE TACO (SOFT OR CRISPY) & ENCHILADA . 11 .99 #2 ONE CHEESE ENCHILADA . 10. .99 #3 ONE CHILE RELLENO & CHEESE ENCHILADA . 12. .25 #4 TWO CHICKEN ENCHILADAS . 12 . .25 #5 TWO GROUND BEEF ENCHILADAS . 12 .25 #6 TWO BEEF TACOS . 11 .50 #7 PORK GREEN CHILE with tortillas . 12 .99 #8 TWO TAQUITOS . 12 .25 Choice of beef or chicken with guacamole #9 CARNITAS PORK (With tortillas) . 12. .99 #10 ONE BEEF TACO . -

Breakfast Burritos Nutrition Information Breakfast Plates Famous Burritos

Nutrition Information Sat Trans Fat Chol Sod Carbs Fiber Sugar Protein Menu Items Cal Fat Fat (g) (mg) (mg) (g) (g) (g) (g) (g) (g) Breakfast Burritos Chorizo Breakfast Burrito 990 55 20 1 395 2490 81 9 7 40 Machaca Burrito - Shredded Chicken 990 48 16 0 445 3360 88 13 9 49 Machaca Burrito - Shredded Beef 950 45 15 0 475 2390 78 10 9 58 Green Pig Burrito 880 41 16 0 470 2900 77 6 7 48 Sunrise Burrito 860 42 16 1 395 3090 77 6 7 40 Spud Burrito 660 26 11 0 395 2480 75 6 6 29 BRC con Huevos Burrito 1090 49 20 0 415 2030 120 13 6 40 Carne Asada Breakfast Burrito 980 41 15 1 425 3750 94 13 7 56 Add Cheese 110 9 5 0 30 190 1 0 0 6 Breakfast Plates Americano Plate - Bacon w/ Flour Tortilla 1070 54 20 0 425 2950 100 15 6 45 Americano Plate - Bacon w/ Corn Tortillas 910 48 16 0 425 2110 83 17 6 40 Americano Plate - Carne Asada w/ Corn Tortillas 970 43 15 0 470 2820 89 20 6 56 Americano Plate - Carne Asada w/ Flour Tortilla 1130 49 19 0 470 3650 106 18 6 61 Americano Plate - Chile Colorado w/ Corn Tortillas 880 42 14 0 430 1870 87 18 8 41 Americano Plate - Chile Colorado w/ Flour Tortillas 1040 48 18 0 430 2710 105 16 8 46 Americano Plate - Chile Verde Pork w/ Corn Tortillas 970 50 18 0 470 1950 85 17 7 47 Americano Plate - Chile Verde Pork w/ Flour Tortilla 1140 57 21 0 470 2790 102 15 7 52 Machaca Plate - Shredded Beef w/ Corn Tortillas 1210 55 18 0 490 2580 120 18 10 63 Machaca Plate - Shredded Beef w/ Flour Tortillas 1370 61 21 0 490 3420 137 16 10 68 Machaca Plate - Shredded Chicken w/ Corn Tortillas 1130 50 16 0 450 3480 120 18 11 51 Machaca -

Receta 5- Pozole De Pollo

POZOLE DE POLLO 5 SERVINGS 10 SERVINGS 16 oz. Pollo 32 oz. Pollo 4 taza de maize en lata 4 taza de maize en lata 2 tazas caldo de pollo 2 tazas caldo de pollo 1 cebolla picada 1 cebolla picada 5 garlic ajos molidos 5 garlic ajos molidos 1 cucharada pasta de tomate 1 cucharada pasta de tomate 2 oz. latas de chile verde 2 oz. latas de chile verde 1 cucharada sazon de chili 1 cucharada sazon de chili 2 cucharaditas cumino 2 cucharaditas cumino 2 cucharaditas oregano 2 cucharaditas oregano 2 cucharaditas sal 2 cucharaditas sal ½ cucharadita sazon de chipotle ½ cucharadita sazon de chipotle 1 limon 1 limon 1 cucharada aceite de oliva 2 cucharada aceite de oliva Para la guarnicion Para la guarnicion 2 aguacates 3 aguacates ½ limon 1 limon Repollo rallado Repollo rallado Rábanos en rodajas Rábanos en rodajas INSTRUCCIONES 1. Coloque el sartén en la estufa a fuego medio-bajo. 2. Caliente el aceite y agregue la cebolla y el ajo, revolviendo junto. Una vez tierno y fragante, agregue los chiles verdes y la pasta de tomate. Agregue chile en polvo, comino, sal, orégano y chipotle molido. 3. Agregue el pollo, el caldo y el maíz cocido. 4. Revuelva bien y deje cocinar durante 25 minutos. 5. Agregue el jugo de lima. Ajuste el nivel de especias y sal. Si su hominy no fue salado, lo más probable es que necesite más. Como esto se asienta en "cálido", los sabores se fundirán y mejorarán. Las sobras, incluso mejor! 6. Sirva con crema agria, aguacate, lima, jalapeño o repollo rallado. -

CHIPOTLE CAESAR Romaine, Cornbread Croutons, Chipotle Lemon Caesar Dressing 13 (Add Chicken Breast +4 Or Carne Asada +6) POZOL

CHIPS & SALSA First round is on us! 3.5 Dinner Menu GUACAMOLE & CHIPS Fresh pomegranate, queso fresco, made-to-order chips 11 AGUACATE FRITO (AVOCADO FRIES) Pomegranate seeds, sliced serrano, cilantro lime salt 12 CEVICHE DE CAMARON Lime-cured Mexican Gulf Shrimp, pico de gallo, avocado, celery, cucumber, lump crab meat 19 IRON SKILLET CORNBREAD Hatch green chilis, fresh corn, citrus honey butter 9 CHICHARRÓN Crispy gold pork belly, lime-marinated red onions, pickled jalapeño, cilantro lime salt 14 TAMALES Two green chicken tamales, topped with tomatillo salsa 11 Molé is proud to present generations of authentic recipes CRAB CAKES Two jumbo lump crab cakes, avocado & tomatillo sauce, onion remoulade 19 made from scratch daily, especially homemade tortillas, salsas, and of course, traditional molé. ¡Buen provecho! CHIPOTLE CAESAR Romaine, cornbread croutons, chipotle lemon caesar dressing 13 (add chicken breast +4 or carne asada +6) WHITES POZOLE ROJO Short rib, hominy, mild red chili, lime, cilantro, cabbage, radish 15 Cava, JAUME SERRA CRISTALINO, Spain 8 / 29 CHILI VERDE Slow-roasted pork shoulder, Oaxaca cheese, charred jalapeño, side of cornbread 14 Riesling, FRISK, 2019, Australia 10 / 37 Rose, ALEXANDER VALLEY, 2019, Alexander Valley 12 / 45 POLLO Organic airline breast, mushroom chipotle cream sauce or chocolate molé 23 Sauvignon Blanc, 2019, CHASING VENUS, Marlborough 12 / 45 CARNE ADOVADA Santa Fe style smoked pork shoulder, charred jalapeño, pico de gallo, guacamole, salsa rojo 25 Pinot Grigio, 2018, MASI MASIANCO, Italy 11 -

The Year of Eating Fabulously So Much Food, So Little Time: Our Favorite Dishes of 2012

the year of eating fabulously So much food, so little time: Our favorite dishes of 2012. STORY BY SCOTT REITZ n PHOTOS BY CATHERINE DOWNES fellow food writer recently told me that food is one of the greatest pleasures of life you get to experience three times a day. If you followed this convention, you’d have more than a thousand opportunities to consume some- thing beautiful every year. Our daily meals seem like an Aalmost endless opportunity for culinary exploration. The thing is, most of us don’t unearth even a fraction of this potential. Breakfast is almost always forgotten. If we eat at all, our morn- ings are often mired in microwavable oatmeal or a terrible bagel sandwich purchased and devoured on the run — hardly inspira- tional eating. So many lunches are squandered on mindless meals we bull- doze in a hurry, collecting our calories at drive-thru win- dows, munching sloppy sandwiches on bad bread from the cafe in an office basement or wolfing down lukewarm Chinese takeout during a quick afternoon break. Dinner seems more sacred, but even this meal falls victim to the countless in- trusions of other important activities in our lives. Our ultimate barrier to plea- surable dining is our demand for con- venience. Unless you have a lot of free time, you probably get only a handful of opportunities a month to go out and eat something wonderful, and those experiences often fall victim to a res- taurant rut. Overwhelmed by recom- mendations offered by newspapers, magazines, blogs and friends, we fall back on our old familiar favorites and then won- der how we ended up stuffed with mediocre Tex-Mex again.