Deciduous Qween Matthew Layne Glasgow Iowa State University

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Drums, Girls, and Dangerous

Drums, Girls & Dangerous Pie Jordan Sonnenblick This one is for my son, Ross Matthew Sonnenblick, who invented Dangerous Pie, and for my daughter, Emma Claire Sonnenblick, who would happily have eaten it. Table of Contents Title Page Dedication DANGEROUS PIE JEFFREY’S MOATMEAL ACCIDENT ANXIETY WITH TIC TACS THE FAT CAT SAT JEFFREY’S VACATION NO MORE VACATION TAKE ME! FEVER TROUBLE STARVING IN SIBERIA POINTLESSNESS AND BOY PERFUME THE SILVER LINING FEAR, GUM, CANDY GOOD NEWS, BAD NEWS CLOSE SHAVES IN AN UNFAIR WORLD THE QUADRUPLE UH-OH A MEN’S JOURNEY I’M A MAN NOW ROCK STAR THE END EPILOGUE ACKNOWLEDGMENTS About the Author Q&A with Jordan Sonnenblick Bonus Material Preview Copyright DANGEROUS PIE There’s a beautiful girl to my left, another to my right. Hundreds of colored balloons are tethered down behind me, baking in the June sun. I’m wearing a brown gown that’s sticking to my sweat-drenched skin, trying to keep my head straight so that my weird square cap doesn’t fall off in front of the thousand people who are watching me. And of course, because I’m me, I’m spacing out. The questions are just tumbling through my mind. “How did I get up here? What have I learned since September? How could my life have possibly changed so much in only ten months?” I’m not even sure I understand the questions, much less where to begin looking for the answers. I guess a good starting point would be the longest journal I’ve ever written in English class. -

Karaoke Mietsystem Songlist

Karaoke Mietsystem Songlist Ein Karaokesystem der Firma Showtronic Solutions AG in Zusammenarbeit mit Karafun. Karaoke-Katalog Update vom: 13/10/2020 Singen Sie online auf www.karafun.de Gesamter Katalog TOP 50 Shallow - A Star is Born Take Me Home, Country Roads - John Denver Skandal im Sperrbezirk - Spider Murphy Gang Griechischer Wein - Udo Jürgens Verdammt, Ich Lieb' Dich - Matthias Reim Dancing Queen - ABBA Dance Monkey - Tones and I Breaking Free - High School Musical In The Ghetto - Elvis Presley Angels - Robbie Williams Hulapalu - Andreas Gabalier Someone Like You - Adele 99 Luftballons - Nena Tage wie diese - Die Toten Hosen Ring of Fire - Johnny Cash Lemon Tree - Fool's Garden Ohne Dich (schlaf' ich heut' nacht nicht ein) - You Are the Reason - Calum Scott Perfect - Ed Sheeran Münchener Freiheit Stand by Me - Ben E. King Im Wagen Vor Mir - Henry Valentino And Uschi Let It Go - Idina Menzel Can You Feel The Love Tonight - The Lion King Atemlos durch die Nacht - Helene Fischer Roller - Apache 207 Someone You Loved - Lewis Capaldi I Want It That Way - Backstreet Boys Über Sieben Brücken Musst Du Gehn - Peter Maffay Summer Of '69 - Bryan Adams Cordula grün - Die Draufgänger Tequila - The Champs ...Baby One More Time - Britney Spears All of Me - John Legend Barbie Girl - Aqua Chasing Cars - Snow Patrol My Way - Frank Sinatra Hallelujah - Alexandra Burke Aber Bitte Mit Sahne - Udo Jürgens Bohemian Rhapsody - Queen Wannabe - Spice Girls Schrei nach Liebe - Die Ärzte Can't Help Falling In Love - Elvis Presley Country Roads - Hermes House Band Westerland - Die Ärzte Warum hast du nicht nein gesagt - Roland Kaiser Ich war noch niemals in New York - Ich War Noch Marmor, Stein Und Eisen Bricht - Drafi Deutscher Zombie - The Cranberries Niemals In New York Ich wollte nie erwachsen sein (Nessajas Lied) - Don't Stop Believing - Journey EXPLICIT Kann Texte enthalten, die nicht für Kinder und Jugendliche geeignet sind. -

Karaoke Catalog Updated On: 11/01/2019 Sing Online on in English Karaoke Songs

Karaoke catalog Updated on: 11/01/2019 Sing online on www.karafun.com In English Karaoke Songs 'Til Tuesday What Can I Say After I Say I'm Sorry The Old Lamplighter Voices Carry When You're Smiling (The Whole World Smiles With Someday You'll Want Me To Want You (H?D) Planet Earth 1930s Standards That Old Black Magic (Woman Voice) Blackout Heartaches That Old Black Magic (Man Voice) Other Side Cheek to Cheek I Know Why (And So Do You) DUET 10 Years My Romance Aren't You Glad You're You Through The Iris It's Time To Say Aloha (I've Got A Gal In) Kalamazoo 10,000 Maniacs We Gather Together No Love No Nothin' Because The Night Kumbaya Personality 10CC The Last Time I Saw Paris Sunday, Monday Or Always Dreadlock Holiday All The Things You Are This Heart Of Mine I'm Not In Love Smoke Gets In Your Eyes Mister Meadowlark The Things We Do For Love Begin The Beguine 1950s Standards Rubber Bullets I Love A Parade Get Me To The Church On Time Life Is A Minestrone I Love A Parade (short version) Fly Me To The Moon 112 I'm Gonna Sit Right Down And Write Myself A Letter It's Beginning To Look A Lot Like Christmas Cupid Body And Soul Crawdad Song Peaches And Cream Man On The Flying Trapeze Christmas In Killarney 12 Gauge Pennies From Heaven That's Amore Dunkie Butt When My Ship Comes In My Own True Love (Tara's Theme) 12 Stones Yes Sir, That's My Baby Organ Grinder's Swing Far Away About A Quarter To Nine Lullaby Of Birdland Crash Did You Ever See A Dream Walking? Rags To Riches 1800s Standards I Thought About You Something's Gotta Give Home Sweet Home -

Songs by Artist

73K October 2013 Songs by Artist 73K October 2013 Title Title Title +44 2 Chainz & Chris Brown 3 Doors Down When Your Heart Stops Countdown Let Me Go Beating 2 Evisa Live For Today 10 Years Oh La La La Loser Beautiful 2 Live Crew Road I'm On, The Through The Iris Do Wah Diddy Diddy When I'm Gone Wasteland Me So Horny When You're Young 10,000 Maniacs We Want Some P---Y! 3 Doors Down & Bob Seger Because The Night 2 Pac Landing In London Candy Everybody Wants California Love 3 Of A Kind Like The Weather Changes Baby Cakes More Than This Dear Mama 3 Of Hearts These Are The Days How Do You Want It Arizona Rain Trouble Me Thugz Mansion Love Is Enough 100 Proof Aged In Soul Until The End Of Time 30 Seconds To Mars Somebody's Been Sleeping 2 Pac & Eminem Closer To The Edge 10cc One Day At A Time Kill, The Donna 2 Pac & Eric Williams Kings And Queens Dreadlock Holiday Do For Love 311 I'm Mandy 2 Pac & Notorious Big All Mixed Up I'm Not In Love Runnin' Amber Rubber Bullets 2 Pistols & Ray J Beyond The Gray Sky Things We Do For Love, The You Know Me Creatures (For A While) Wall Street Shuffle 2 Pistols & T Pain & Tay Dizm Don't Tread On Me We Do For Love She Got It Down 112 2 Unlimited First Straw Come See Me No Limits Hey You Cupid 20 Fingers I'll Be Here Awhile Dance With Me Short Dick Man Love Song It's Over Now 21 Demands You Wouldn't Believe Only You Give Me A Minute 38 Special Peaches & Cream 21st Century Girls Back Where You Belong Right Here For You 21St Century Girls Caught Up In You U Already Know 3 Colours Red Hold On Loosely 112 & Ludacris Beautiful Day If I'd Been The One Hot & Wet 3 Days Grace Rockin' Into The Night 12 Gauge Home Second Chance Dunkie Butt Just Like You Teacher, Teacher 12 Stones 3 Doors Down Wild Eyed Southern Boys Crash Away From The Sun 3LW Far Away Be Like That I Do (Wanna Get Close To We Are One Behind Those Eyes You) 1910 Fruitgum Co. -

Songs by Artist

Sound Master Entertianment Songs by Artist smedenver.com Title Title Title .38 Special 2Pac 4 Him Caught Up In You California Love (Original Version) For Future Generations Hold On Loosely Changes 4 Non Blondes If I'd Been The One Dear Mama What's Up Rockin' Onto The Night Thugz Mansion 4 P.M. Second Chance Until The End Of Time Lay Down Your Love Wild Eyed Southern Boys 2Pac & Eminem Sukiyaki 10 Years One Day At A Time 4 Runner Beautiful 2Pac & Notorious B.I.G. Cain's Blood Through The Iris Runnin' Ripples 100 Proof Aged In Soul 3 Doors Down That Was Him (This Is Now) Somebody's Been Sleeping Away From The Sun 4 Seasons 10000 Maniacs Be Like That Rag Doll Because The Night Citizen Soldier 42nd Street Candy Everybody Wants Duck & Run 42nd Street More Than This Here Without You Lullaby Of Broadway These Are Days It's Not My Time We're In The Money Trouble Me Kryptonite 5 Stairsteps 10CC Landing In London Ooh Child Let Me Be Myself I'm Not In Love 50 Cent We Do For Love Let Me Go 21 Questions 112 Loser Disco Inferno Come See Me Road I'm On When I'm Gone In Da Club Dance With Me P.I.M.P. It's Over Now When You're Young 3 Of Hearts Wanksta Only You What Up Gangsta Arizona Rain Peaches & Cream Window Shopper Love Is Enough Right Here For You 50 Cent & Eminem 112 & Ludacris 30 Seconds To Mars Patiently Waiting Kill Hot & Wet 50 Cent & Nate Dogg 112 & Super Cat 311 21 Questions All Mixed Up Na Na Na 50 Cent & Olivia 12 Gauge Amber Beyond The Grey Sky Best Friend Dunkie Butt 5th Dimension 12 Stones Creatures (For A While) Down Aquarius (Let The Sun Shine In) Far Away First Straw AquariusLet The Sun Shine In 1910 Fruitgum Co. -

2 Column Indented

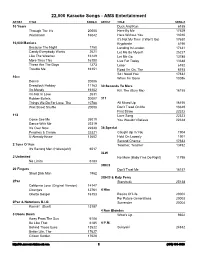

22,000 Karaoke Songs - AMS Entertainment ARTIST TITLE SONG # ARTIST TITLE SONG # 10 Years Duck And Run 6188 Through The Iris 20005 Here By Me 17629 Wasteland 16042 Here Without You 13010 It's Not My Time (I Won't Go) 17630 10,000 Maniacs Kryptonite 6190 Because The Night 1750 Landing In London 17631 Candy Everybody Wants 2621 Let Me Be Myself 25227 Like The Weather 16149 Let Me Go 13785 More Than This 16150 Live For Today 13648 These Are The Days 1273 Loser 6192 Trouble Me 16151 Road I'm On, The 6193 So I Need You 17632 10cc When I'm Gone 13086 Donna 20006 Dreadlock Holiday 11163 30 Seconds To Mars I'm Mandy 16152 Kill, The (Bury Me) 16155 I'm Not In Love 2631 Rubber Bullets 20007 311 Things We Do For Love, The 10788 All Mixed Up 16156 Wall Street Shuffle 20008 Don't Tread On Me 13649 First Straw 22322 112 Love Song 22323 Come See Me 25019 You Wouldn't Believe 22324 Dance With Me 22319 It's Over Now 22320 38 Special Peaches & Cream 22321 Caught Up In You 1904 U Already Know 13602 Hold On Loosely 1901 Second Chance 17633 2 Tons O' Fun Teacher, Teacher 13492 It's Raining Men (Hallelujah!) 6017 3LW 2 Unlimited No More (Baby I'ma Do Right) 11795 No Limits 6183 3Oh!3 20 Fingers Don't Trust Me 16157 Short Dick Man 1962 3OH!3 & Katy Perry 2Pac Starstrukk 25138 California Love (Original Version) 14147 Changes 12761 4 Him Ghetto Gospel 16153 Basics Of Life 20002 For Future Generations 20003 2Pac & Notorious B.I.G. -

Songs by Artist

Songs by Artist Karaoke Collection Title Title Title +44 18 Visions 3 Dog Night When Your Heart Stops Beating Victim 1 1 Block Radius 1910 Fruitgum Co An Old Fashioned Love Song You Got Me Simon Says Black & White 1 Fine Day 1927 Celebrate For The 1st Time Compulsory Hero Easy To Be Hard 1 Flew South If I Could Elis Comin My Kind Of Beautiful Thats When I Think Of You Joy To The World 1 Night Only 1st Class Liar Just For Tonight Beach Baby Mama Told Me Not To Come 1 Republic 2 Evisa Never Been To Spain Mercy Oh La La La Old Fashioned Love Song Say (All I Need) 2 Live Crew Out In The Country Stop & Stare Do Wah Diddy Diddy Pieces Of April 1 True Voice 2 Pac Shambala After Your Gone California Love Sure As Im Sitting Here Sacred Trust Changes The Family Of Man 1 Way Dear Mama The Show Must Go On Cutie Pie How Do You Want It 3 Doors Down 1 Way Ride So Many Tears Away From The Sun Painted Perfect Thugz Mansion Be Like That 10 000 Maniacs Until The End Of Time Behind Those Eyes Because The Night 2 Pac Ft Eminem Citizen Soldier Candy Everybody Wants 1 Day At A Time Duck & Run Like The Weather 2 Pac Ft Eric Will Here By Me More Than This Do For Love Here Without You These Are Days 2 Pac Ft Notorious Big Its Not My Time Trouble Me Runnin Kryptonite 10 Cc 2 Pistols Ft Ray J Let Me Be Myself Donna You Know Me Let Me Go Dreadlock Holiday 2 Pistols Ft T Pain & Tay Dizm Live For Today Good Morning Judge She Got It Loser Im Mandy 2 Play Ft Thomes Jules & Jucxi So I Need You Im Not In Love Careless Whisper The Better Life Rubber Bullets 2 Tons O Fun -

Barrett Anderson Band John Nemeth Mark Dix Eddie Van Halen Tribute

•Our 35th Year Proudly Promoting All Things Music• FREE! November 2020 Eddie Van Halen Tribute Mark Dix John Nemeth Barrett Anderson Band Remembering Eddie Van Halen The rock world lost one if its true Santa Monica, California on October 6, were naturalized as U.S. citizens. bought a drum kit, however, after he guitar innovators on October 6, 2020. 2020, at age 65. The brothers learned to play the piano heard Alex play The Surfaris’ drum solo Eddie Van Halen, songwriter and lead Edward Lodewijk Van Halen was born starting at age six. Eddie revealed that in the song “Wipe Out” on the drums, guitarist for the band of the same name, on January 26, 1955 in Amsterdam, he had never been able to read music. he decided to switch instruments and lost his battle to cancer. Known for his Netherlands. He was the son of Jan Instead, he learned from watching and began learning how to play the electric heavy cigarette smoking guitar. He would often since age 12 on top of practice while walking drug and alcohol use around at home with throughout his career, his guitar strapped on Eddie began receiving or sitting in his room treatment for tongue for hours with the door cancer in 2000. He locked. underwent surgery that Eddie and Alex formed removed a third of his their first band with tongue. He was declared three other boys, calling cancer-free in 2002. themselves The Broken He blamed the tongue Combs at Hamilton cancer on his habit of Elementary School in holding guitar picks in Pasadena. -

Karaoke Catalog Updated On: 17/12/2016 Sing Online on in English Karaoke Songs

Karaoke catalog Updated on: 17/12/2016 Sing online on www.karafun.com In English Karaoke Songs (H?D) Planet Earth My One And Only Hawaiian Hula Eyes Blackout I Love My Baby (My Baby Loves Me) On The Beach At Waikiki Other Side I'll Build A Stairway To Paradise Deep In The Heart Of Texas 10 Years My Blue Heaven What Are You Doing New Year's Eve Through The Iris What Can I Say After I Say I'm Sorry Long Ago And Far Away 10,000 Maniacs When You're Smiling (The Whole World Smiles With Bésame mucho (English Vocal) Because The Night 'S Wonderful For Me And My Gal 10CC 1930s Standards 'Til Then Dreadlock Holiday Let's Call The Whole Thing Off Daddy's Little Girl I'm Not In Love Heartaches The Old Lamplighter The Things We Do For Love Cheek To Cheek Someday You'll Want Me To Want You Rubber Bullets Love Is Sweeping The Country That Old Black Magic (Woman Voice) Life Is A Minestrone My Romance That Old Black Magic (Man Voice) 112 It's Time To Say Aloha I Know Why (And So Do You) DUET Cupid We Gather Together Aren't You Glad You're You Peaches And Cream Kumbaya (I've Got A Gal In) Kalamazoo 12 Gauge The Last Time I Saw Paris My One And Only Highland Fling Dunkie Butt All The Things You Are No Love No Nothin' 12 Stones Smoke Gets In Your Eyes Personality Far Away Begin The Beguine Sunday, Monday Or Always Crash I Love A Parade This Heart Of Mine 1800s Standards I Love A Parade (short version) Mister Meadowlark Home Sweet Home I'm Gonna Sit Right Down And Write Myself A Letter 1950s Standards Home On The Range Body And Soul Get Me To The Church On -

Nostalgia and Hapa Haole Music in Early

, (y u'\'iA!ILlBK"""j UNIVERSIITY -- - ,. I'LL REMEMBER YOU: NOSTALGIA AND HAPA HAOLE MUSIC IN EARLY TWENTY-FIRST CENTURY HAWAI'I A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE DIVISION OF THE UNIVERSITY OF HA WAI'I IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS IN MUSIC AUGUST 2007 by Masaya Shishikura Thesis Committee: Ricardo D. Trimillos, Chairperson Frederick Lau Christine R. Yano , ii, We certify that we have read this thesis and that, in our opinion, it is satisfactory in scope and quality as a thesis for the degree of Master of Arts in Music THESIS COMMITTEE ~~~'~ Chairperson + HAWN CB5 .H3 no. 3~2~ , III Copyright by Masaya Shishikura 2007 All Rights Reserved IV DEDICATION This is dedicated to my parents Makoto and Hiroko Shishikura v ACKNOWLEDGMENTS After passing this thesis defense and coming back to Japan, within a month, Hawai'i and its people became nostalgic to me. I miss the large plate lunch, the gentle rain showers and the people, who collaborated and supported this thesis. I would like to acknowledge them briefly below. First, I thank my thesis committee members: Drs. Ricardo D. Trimillos, Frederick Lau and Christine R. Yano. They patiently kept on encouraging and advising me in the course of writing. Also, my gratitude extends to Dr. Ty P. Kawika Tengan, who acted as a proxy of Dr. Yano in the defense. All of them gave me insightful comments and suggestions, which are included in this thesis. All the classes at the University of Hawai'i at Manoa helped me to establish scholarship as an ethnomusicologist. -

Tony G DJ and Karaoke Services 520-250-8669 [email protected]

Tony G DJ and Karaoke Services 520-250-8669 [email protected] 10 CC - I'm Not In Love 99 Problems - Hugo Abba - Waterloo 10,000 Maniacs - Candy Everybody WantsA Chorus Line- At The Ballet Abelardo Pulido Buenrostro - Entrega Total 10,000 Maniacs - More Than This A Cruz Lavana - Qiero Una Novia PechugonaAC DC - Back In Black 10,000 Maniacs - These Are The Days 10,000A Day Maniacs To Remember • If It Means a Lot toAC You DC - Big Balls 10,000 Maniacs - Trouble Me A Great Big World ft. Futuristic - Hold EachAC Other DC - Dirty Deeds Done Dirt Cheap 112 - Dance With Me A Great Big World, Christina Aguilera - SayAC Something DC - Girls Got( Version, Rhythm No Backing 112 Feat Ludacris - Hot and Wet (Rap) Vocals) AC DC - Hard As A Rock 1910 Fruitgum Co. - Simon Says A Little Dive Bar In Dahlonega (In the StyleA Cof DC Ashley - Hell's McBride) Bells with 2 Live Crew - Me So Horny (Rap) A New Found Glory - Heaven AC DC - It's A Long Way To The Top 21 Savage - Bank Account A Perfect Circle - Judith AC DC - Money Talks 3 Doors Down - Be Like That A Perfect Circle - Weak and Powerless AC DC - Problem Child 3 Doors Down - Here Without You A Taste Of Honey - Boogie Oogie Oogie Ac Dc - Sin City 3 Doors Down - Kryptonite A Través Del Vaso - - Grupo Arranke AC DC - Stiff Upper Lip 3 Doors Down - Kryptonite A. Campbell & L. Mann - Dark End Of TheAC Street DC - Thunderstruck 3 Doors Down - When I’m Gone A. -

Songs by Artist

Nice N Easy Karaoke Songs by Artist Bookings - Arie 0401 097 959 10 Years 50 Cent A1 Through The Iris 21 Questions Everytime 10Cc Candy Shop Like A Rose Im Not In Love In Da Club Make It Good Things We Do For Love In Da' Club No More 112 Just A Lil Bit Nothing Dance With Me Pimp Remix Ready Or Not Peaches Cream Window Shopper Same Old Brand New You 12 Stones 50 Cent & Olivia Take On Me Far Away Best Friend A3 1927 50 Cents Woke Up This Morning Compulsory Hero Just A Lil Bit Aaliyah Compulsory Hero 2 50 Cents Ft Eminem & Adam Levine Come Over If I Could My Life (Clean) I Don't Wanna 2 Pac 50 Cents Ft Snoop Dogg & Young Miss You California Love Major Distribution (Clean) More Than A Woman Dear Mama 5Th Dimension Rock The Boat Until The End Of Time One Less Bell To Answer Aaliyah & Timbaland 2 Unlimited 5Th Dimension The We Need A Resolution No Limit Aquarius Let The Sun Shine In Aaliyah Feat Timbaland 20 Fingers Stoned Soul Picnic We Need A Resolution Short Dick Man Up Up And Away Aaron Carter 3 Doors Down Wedding Bell Blues Aaron's Party (Come And Get It) Away From The Sun 702 Bounce Be Like That I Still Love You How I Beat Shaq Here Without You 98 Degrees I Want Candy Kryptonite Hardest Thing The Aaron Carter & Nick Landing In London I Do Cherish You Not Too Young, Not Too Old Road Im On The Way You Want Me To Aaron Carter & No Secrets When Im Gone A B C Oh, Aaron 3 Of Hearts Look Of Love Aaron Lewis & Fred Durst Arizona Rain A Brooks & Dunn Outside Love Is Enough Proud Of The House We Built Aaron Lines 3 Oh 3 A Girl Called Jane Love Changes