The Restoring Ancient Stabiae Foundation Has Embraced with Enthusiasm the Opportunity of Presenting to the U.S

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Special Superintendency for Pompeii, Herculaneum and Stabiae

SPECIAL SUPERINTENDENCY FOR POMPEII, HERCULANEUM AND STABIAE SERVICE CHARTER OF THE ARCHAEOLOGICAL AREA of the STABIAE EXCAVATION STABIAE EXCAVATION Via Passeggiata Archeologica, 80053 Castellammare di Stabia (Naples) telephone and fax number: +39 081 / 8714541 e‐mail address: ssba- [email protected] [email protected] website: www.pompeiisites.org P R E S E N T A T I O N WHAT IS THE SERVICE CHARTER The Service Charter establishes principles and rules governing the relations between the central and local government authorities providing the services and the citizens that use them. The Charter is an agreement between the provider and the users. It is a tool to communicate with and inform users about the services offered, and the procedures and standards set. It also ensures that any commitments are fulfilled, and that any suggestions or complaints may be made by filling out the appropriate forms if necessary. The Service Charter was adopted by the institutes of the Ministry of Cultural Heritage and Activities and Tourism as part of a series of initiatives aimed at promoting a greater enhancement of the cultural heritage being preserved, and at meeting the expectations of the users about the organisation of events while respecting the requirements of preservation and research. The Charter will be periodically updated to consolidate the quality levels reached and record any positive changes produced by running improvement projects. Such improvements may also be a result of user feedback. THE PRINCIPLES In performing its institutional activity, the Archaeological Area of the STABIAE EXCAVATION draws inspiration from the “fundamental principles” set out in the Directive issued by the President of the Council of Ministers on 27th January 1994: Equality and Fairness In providing our services, we are committed to the principle of fairness, ensuring an equality for all citizens regardless of origin, sex, language, religion, or political persuasion. -

Map 44 Latium-Campania Compiled by N

Map 44 Latium-Campania Compiled by N. Purcell, 1997 Introduction The landscape of central Italy has not been intrinsically stable. The steep slopes of the mountains have been deforested–several times in many cases–with consequent erosion; frane or avalanches remove large tracts of regolith, and doubly obliterate the archaeological record. In the valley-bottoms active streams have deposited and eroded successive layers of fill, sealing and destroying the evidence of settlement in many relatively favored niches. The more extensive lowlands have also seen substantial depositions of alluvial and colluvial material; the coasts have been exposed to erosion, aggradation and occasional tectonic deformation, or–spectacularly in the Bay of Naples– alternating collapse and re-elevation (“bradyseism”) at a staggeringly rapid pace. Earthquakes everywhere have accelerated the rate of change; vulcanicity in Campania has several times transformed substantial tracts of landscape beyond recognition–and reconstruction (thus no attempt is made here to re-create the contours of any of the sometimes very different forerunners of today’s Mt. Vesuvius). To this instability must be added the effect of intensive and continuous intervention by humanity. Episodes of depopulation in the Italian peninsula have arguably been neither prolonged nor pronounced within the timespan of the map and beyond. Even so, over the centuries the settlement pattern has been more than usually mutable, which has tended to obscure or damage the archaeological record. More archaeological evidence has emerged as modern urbanization spreads; but even more has been destroyed. What is available to the historical cartographer varies in quality from area to area in surprising ways. -

Recent Work on the Stone at the Villa Arianna and the Villa San Marco (Castellammare Di Stabia) and Their Context Within the Vesuvian Area

Recent Work on the Stone at the Villa Arianna and the Villa San Marco (Castellammare di Stabia) and Their Context within the Vesuvian Area Barker, Simon J.; Fant, J. Clayton Source / Izvornik: ASMOSIA XI, Interdisciplinary Studies on Ancient Stone, Proceedings of the XI International Conference of ASMOSIA, 2018, 65 - 78 Conference paper / Rad u zborniku Publication status / Verzija rada: Published version / Objavljena verzija rada (izdavačev PDF) https://doi.org/10.31534/XI.asmosia.2015/01.04 Permanent link / Trajna poveznica: https://urn.nsk.hr/urn:nbn:hr:123:583276 Rights / Prava: In copyright Download date / Datum preuzimanja: 2021-10-05 Repository / Repozitorij: FCEAG Repository - Repository of the Faculty of Civil Engineering, Architecture and Geodesy, University of Split ASMOSIA PROCEEDINGS: ASMOSIA I, N. HERZ, M. WAELKENS (eds.): Classical Marble: Geochemistry, Technology, Trade, Dordrecht/Boston/London,1988. e n ASMOSIA II, M. WAELKENS, N. HERZ, L. MOENS (eds.): o t Ancient Stones: Quarrying, Trade and Provenance – S Interdisciplinary Studies on Stones and Stone Technology in t Europe and Near East from the Prehistoric to the Early n Christian Period, Leuven 1992. e i ASMOSIA III, Y. MANIATIS, N. HERZ, Y. BASIAKOS (eds.): c The Study of Marble and Other Stones Used in Antiquity, n London 1995. A ASMOSIA IV, M. SCHVOERER (ed.): Archéomatéiaux – n Marbres et Autres Roches. Actes de la IVème Conférence o Internationale de l’Association pour l’Étude des Marbres et s Autres Roches Utilisés dans le Passé, Bordeaux-Talence 1999. e i d ASMOSIA V, J. HERRMANN, N. HERZ, R. NEWMAN (eds.): u ASMOSIA 5, Interdisciplinary Studies on Ancient Stone – t Proceedings of the Fifth International Conference of the S Association for the Study of Marble and Other Stones in y Antiquity, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, June 1998, London r 2002. -

Herculaneum Archaeology

I In this edition: Ercolano Meeting, June 2010 - report by Robert Fowler, Trustee Herculaneum: an Ancient Town in the Bay of Naples - Christopher Smith, Director of the British School in Rome Pompeii and the Roman Villa: Art and Culture around the Bay of Naples. Report on the exhibition by Carol Mattusch House of the Relief of Telephus, Herculaneum herculaneum archaeology herculaneum Society - Issue 12 Summer 2010 of the Friends Herculaneum the newsletter Suburban Baths, not normally open to the public, and a peak inside the Bourbon tunnels in the Basilica—this was The Third Herculaneum a particular treat, as one could see some quite breathtaking original frescoes in situ, untouched by any restoration. The Conference narrow space could accommodate only three or four tightly Robert Fowler squeezed people at a time. 2. 3. 4. The Suburban Baths 1. The Gardens of the Miglio d’Oro The Friends met 11–13 June for their third gathering in Campania since 2006, in what is now an established biennial tradition. For repeat attenders it felt like a reunion, while at the same time it was gratifying to welcome a good number of newcomers. For the first two meetings we resided in Naples (hence the First and Second ‘Naples’ Congresses), but for this one we moved out to Ercolano itself, a prospect made enticing by the opening of the four-star Miglio D’Oro hotel, a spectacular, done-over 18th-century villa which made up in atmosphere—especially the garden—what it (so far) lacks in abundance of staff (in some areas). The experiment was judged successful both for its convenience and for the benefit we were able to deliver to the local economy, not just the Miglio D’Oro but to B&Bs and local businesses. -

The Monumental Villa at Palazzi Di Casignana and the Roman Elite in Calabria (Italy) During the Fourth Century AD

The Monumental Villa at Palazzi di Casignana and the Roman Elite in Calabria (Italy) during the Fourth Century AD. by Maria Gabriella Bruni A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the Requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Classical Archaeology in the GRADUATE DIVISION of the UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Committee in Charge Professor Christopher H. Hallett, Chair Professor Ronald S. Stroud Professor Anthony W. Bulloch Professor Carlos F. Noreña Fall 2009 The Monumental Villa at Palazzi di Casignana and the Roman Elite in Calabria (Italy) during the Fourth Century AD. Copyright 2009 Maria Gabriella Bruni Dedication To my parents, Ken and my children. i AKNOWLEDGMENTS I am extremely grateful to my advisor Professor Christopher H. Hallett and to the other members of my dissertation committee. Their excellent guidance and encouragement during the major developments of this dissertation, and the whole course of my graduate studies, were crucial and precious. I am also thankful to the Superintendence of the Archaeological Treasures of Reggio Calabria for granting me access to the site of the Villa at Palazzi di Casignana and its archaeological archives. A heartfelt thank you to the Superintendent of Locri Claudio Sabbione and to Eleonora Grillo who have introduced me to the villa and guided me through its marvelous structures. Lastly, I would like to express my deepest gratitude to my husband Ken, my sister Sonia, Michael Maldonado, my children, my family and friends. Their love and support were essential during my graduate -

Pompeii and Herculaneum: a Sourcebook Allows Readers to Form a Richer and More Diverse Picture of Urban Life on the Bay of Naples

POMPEII AND HERCULANEUM The original edition of Pompeii: A Sourcebook was a crucial resource for students of the site. Now updated to include material from Herculaneum, the neighbouring town also buried in the eruption of Vesuvius, Pompeii and Herculaneum: A Sourcebook allows readers to form a richer and more diverse picture of urban life on the Bay of Naples. Focusing upon inscriptions and ancient texts, it translates and sets into context a representative sample of the huge range of source material uncovered in these towns. From the labels on wine jars to scribbled insults, and from advertisements for gladiatorial contests to love poetry, the individual chapters explore the early history of Pompeii and Herculaneum, their destruction, leisure pursuits, politics, commerce, religion, the family and society. Information about Pompeii and Herculaneum from authors based in Rome is included, but the great majority of sources come from the cities themselves, written by their ordinary inhabitants – men and women, citizens and slaves. Incorporating the latest research and finds from the two cities and enhanced with more photographs, maps and plans, Pompeii and Herculaneum: A Sourcebook offers an invaluable resource for anyone studying or visiting the sites. Alison E. Cooley is Reader in Classics and Ancient History at the University of Warwick. Her recent publications include Pompeii. An Archaeological Site History (2003), a translation, edition and commentary of the Res Gestae Divi Augusti (2009), and The Cambridge Manual of Latin Epigraphy (2012). M.G.L. Cooley teaches Classics and is Head of Scholars at Warwick School. He is Chairman and General Editor of the LACTOR sourcebooks, and has edited three volumes in the series: The Age of Augustus (2003), Cicero’s Consulship Campaign (2009) and Tiberius to Nero (2011). -

The Fury of Vesuvius Pompeii and Herculaneum

The Fury of Vesuvius Pompeii and Herculaneum . Pompeii Lost . Herculaneum Burned . Trapped in Stabiae . Ash Covers Misenum . Exploring Modern Pompeii Written by Marian Vermeulen This free Book is offered to you by Timetravelrome - a Mobile App that finds and describes every significant ancient Roman city, fortress, theatre, or sanctuary in Europe, Middle East as well as across North Africa. www.timetravelrome.com 2 Part I TimeTravelRome || The Fury of Vesuvius Part I : Pompeii Lost Pompeii Lost Pompeii was one of the Roman cities that enjoyed the volcanic soils of Campania, the region surrounding Vesuvius. Pliny the Elder once called the area one of the loveliest places on earth. Vesuvius had not erupted since the Bronze Age, and the Romans believed that the volcano was dead. Although occasional earthquakes rocked the area, the most violent being in 62 or 63 A.D., the inhabitants did not connect the vibrations to the long silent mountain. On October 24th, 79 A.D.,* catastrophe struck, and Pompeii was lost to the fury of Vesuvius. The poignant stories of the people of Pompeii are heartbreaking, and sometimes difficult to read, but must be told. Eruption During the summer of 79 A.D., the fires built beneath the mountain. Small tremors increased to the point of becoming a normal part of life. The shifting of the earth cut off Pompeii’s water supply, and the volcano rumbled and growled. The citizens of Pompeii spent a sleepless night on the 23rd of October, as the shocks grew frequent and violent. When morning dawned, they rose to begin their day as usual. -

Campania Region Pompeii, Herculaneum, Oplontis, Paestum, Aeclan- Um, Stabiae and Velia

Campania Region Pompeii, Herculaneum, Oplontis, Paestum, Aeclan- um, Stabiae and Velia. The name of Campania is de- Located on the south-western portion of the Italian rived from Latin, as Peninsula, with the Tyrrhenian Sea to the west, it in- the Romans knew the cludes the small Phlegraean Islands and Capri. It is region as Campania felix, the most densely populated region in the country. which translates into Campania is the most productive region in southern English as "fertile coun- Italy by GDP, and Naples' urban area is the 9th-most tryside" or "happy coun- tryside". The rich natural beauty of Campania makes it highly important in the tourism industry. Campania was a full- fledged part of the Roman Republic by the end of the 4th centu- ry BC, valued for its pastures and rich countryside. Naples, with its Greek language and customs, made it a cen- ter of Hellenistic culture for the Romans, creating the first traces of Greco-Roman culture, the area had many duchies and principalities during the Middle Ages, in the hands of the Byzantine Empire (also re- populous in the European Union. The region is home ferred to as the Eastern Roman Empire) and to 10 of the 55 UNESCO sites in Italy, like Pompeii and Herculaneum, the Royal Palace of Caserta, the Amalfi Coast and the Historic Centre of Naples. Moreover, Mount Vesuvius is part of the UNESCO World Network of Biosphere Reserves. Coastal areas in the region were colonized by the Ancient Greeks between the 8th and 7th centu- ries BC, becoming part of the so-called Magna Græcia. -

Stabiae Master Plan INGLESE 28-06-2006 9:38 Pagina 2

Stabiae Master Plan COPERTINA ING 28-06-2006 9:49 Pagina 3 Summary A Project of the Superintendancy of Archaeology of Pompei, coordinated by the Restoring Ancient Stabiae Foundation, to create one of the largest archaeological parks in modern Europe on the site of the ancient Roman Villas of Stabiae Supported and monitored by Italian and U.S. governments as an innovative pilot project in the collaborative international management of Italian cultural heritage, and a project key to cultural and economic revival in Southern Italy Master Plan 2006 The Restoring Ancient Stabiae Foundation is an Italian non-profit cultural foundation, with international board representation from: The Archaeological Superintendancy of Pompeii School of Architecture of the University of Maryland The Committee of Stabiae Reborn Stabiae Master Plan INGLESE 28-06-2006 9:38 Pagina 2 Pompeii, Herculaneum, Boscoreale, and the new Archaeological Park of Stabiae ISCHIA MISENUM BAIAE NAPLES HERCULANEUM < TO SORRENTO MODERN CASTELLAMMARE Recovering the Total Villa Environment of the Roman Elite The site of ancient Stabiae is the largest con- came first to the Bay of Naples, not Rome, to centration of excellently preserved, enor- solidify his support. mous, elite seaside villas in the entire Roman These great seaside display villas were new world. phenomena in world architecture in the first Ancient Roman Stabiae (modern Castellam- century B.C. They featured numerous dining mare di Stabia) is very different from nearby rooms with calculated panoramic views of Pompeii or Herculaneum. It was buried in the sea and mountains, private heated baths, same cataclysmic eruption of A.D. 79 and like art collections and libraries, cooling those sites, is also gorgeously preserved by fountains and gardens, huge co- the ash and cinder. -

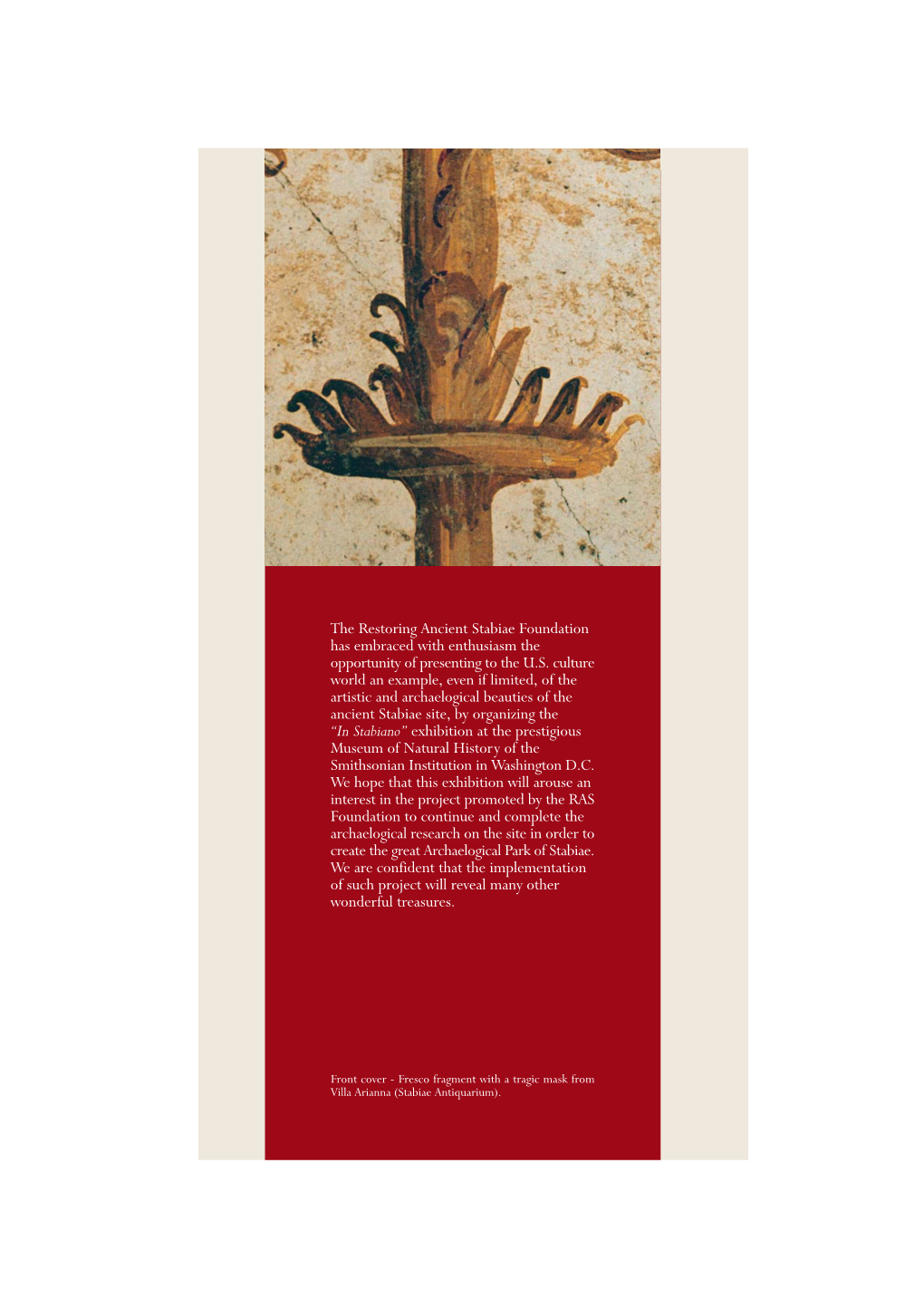

In Stabiano: Exploring the Ancient Seaside Villas of the Roman Elite a Special Exhibition Review by Gail S

Art History In Stabiano: Exploring the Ancient Seaside Villas of the Roman Elite A Special Exhibition Review by Gail S. Myhre The United States tour of the exhibition In Stabiano: Exploring the Ancient Seaside Villas of the Roman Elite began at the National Museum of Natural History, The Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C. All of the materials on exhibition date to the period of reconstruction between the sacking of Stabiae by the Roman general Sulla in 89 B.C. and the Vesuvian eruption of A.D. 79 which also destroyed Pompeii and Herculaneum. I glimpsed this exhibition briefly during a visit to the National Museum of Natural History in 2004, and was delighted by this opportunity to review the exhibition in its entirety at the Michael C. Carlos Museum in Atlanta, Georgia. The Michael C. Carlos Museum is affiliated with and located on the campus of Emory University. Its permanent collections are well endowed for a museum of its size, and this special exhibition is a fine addition to the well-curated portion which treats classical Greek and Roman art. Entering the exhibition in this venue one came immediately upon the full reconstruction of the triclinium or dining room from the Villa Carmiano. Looking into the room, the beautifully preserved Fourth Style frescoes on these walls featured Bacchus and Ceres to the left, the Triumph of Dionysus facing, and Neptune and Amymone to the right. The triclinium would have opened out onto a view, probably facing the sea. It was traditional that the room's middle couch was that on which the host and the favored guests rested, giving them the best vantage. -

NACCP News Fall 10.Indd

NEWSLETTER No. 40, Autumn 2010 What a Week at the Shore with the Caecilians! July workshop participants find a shady spot for a photograph in the atrium of Caecilius’ house. Photo from Shannon Stieg. Below, Melody Hannegan, NACCP Workshop Coordinator, reports on the success of this ambitious project. Only a year and a half has passed since the inception of our work on the NACCP Castellammare-based workshop, and I cannot believe it is now a fond memory. My initial goal was to offer an affordable opportunity for Cambridge Latin Course teachers to experience an intensive week in the area that Caecilius called home and that so many of us call home today in our classrooms. As is the case with any trip to the shore, we encountered unavoidable circumstances such as excessive heat, a lack of air-conditioning, lost luggage and sometimes-noisy neighbors countered by gorgeous scenery, breezes in the shade, newly-discovered sights, and mouth-watering culinary delights. What really made the trip, however, were the people involved. I would like to acknowledge Audrey Fastuca and the staff at the Vesuvian International Institute in Castellammare di Stabia for housing and feeding us so graciously during our stay in Italy. In addition, Audrey led our tour of the two Stabian villas and arranged for a wonderful presentation by Synaulia, an in-residence group of musicians and dancers of ancient music. Many thanks to Domenica Luisi at Georgia Hardy Tours for arranging air transportation. Giovanni Fattore served as our able Italian tour guide at most of the archaeological sites. -

Campania/Rv Schoder. Sj

CAMPANIA/R.V. SCHODER. S. J. RAYMOND V. SCHODER, S.J. (1916-1987) Classical Studies Department SLIDE COLLECTION OF CAMPANIA Prepared by: Laszlo Sulyok Ace. No. 89-15 Computer Name: CAMPANIA.SCH 1 Metal Box Location: Room 209/ The following slides of Campanian Art are from the collection of Raymond V. Schader, S.J. They are arranged alpha-numerically in the order in which they were received at the archives. The notes in the inventory were copied verbatim from Schader's own citations on the slides. CAUTION: This collection may include commercially produced slides which may only be reproduced with the owner's permission. I. PHELGRAEA, Nisis, Misenum, Procida (bk), Baiae bay, fr. Pausilp 2. A VERNUS: gen., w. Baiae thru gap 3. A VERNUS: gen., w. Misenum byd. 4. A VERN US: crater 5. A VERN US: crater 6. A VERNUS: crater in!. 7. AVERNUS: E edge, w. Baths, Mt. Nuovo 1538 8. A VERNUS: Tunnel twd. Lucrinus: middle 9. A VERNUS: Tunnel twd. Lucrinus: stairs at middle exit fl .. 10. A VERNUS: Tunnel twd. Lucr.: stairs to II. A VERNUS: Tunnel twd. Lucrinus: inner room (Off. quarters?) 12. BAIAE CASTLE, c. 1540, by Dom Pedro of Toledo; fr. Pozz. bay 13. BAIAE: Span. 18c. castle on Caesar Villa site, Capri 14. BAIAE: Gen. E close, tel. 15. BAIAE: Gen. E across bay 16. BAIAE: terrace arch, stucco 17. BAIAE: terraces from below 18. BAIAE: terraces arcade 19. BAIAE: terraces gen. from below 20. BAIAE: Terraces close 21. BAIAE: Bay twd. Lucrinus; Vesp. Villa 22. BAIAE: Palaestra(square), 'T.