Bernard of Clairvaux

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Antiphonary of Bangor and Its Musical Implications

The Antiphonary of Bangor and its Musical Implications by Helen Patterson A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Graduate Department of Music University of Toronto © Copyright by Helen Patterson 2013 The Antiphonary of Bangor and its Musical Implications Helen Patterson Doctor of Philosophy Graduate Department of Music University of Toronto 2013 Abstract This dissertation examines the hymns of the Antiphonary of Bangor (AB) (Antiphonarium Benchorense, Milan, Biblioteca Ambrosiana C. 5 inf.) and considers its musical implications in medieval Ireland. Neither an antiphonary in the true sense, with chants and verses for the Office, nor a book with the complete texts for the liturgy, the AB is a unique Irish manuscript. Dated from the late seventh-century, the AB is a collection of Latin hymns, prayers and texts attributed to the monastic community of Bangor in Northern Ireland. Given the scarcity of information pertaining to music in early Ireland, the AB is invaluable for its literary insights. Studied by liturgical, medieval, and Celtic scholars, and acknowledged as one of the few surviving sources of the Irish church, the manuscript reflects the influence of the wider Christian world. The hymns in particular show that this form of poetical expression was significant in early Christian Ireland and have made a contribution to the corpus of Latin literature. Prompted by an earlier hypothesis that the AB was a type of choirbook, the chapters move from these texts to consider the monastery of Bangor and the cultural context from which the manuscript emerges. As the Irish peregrini are known to have had an impact on the continent, and the AB was recovered in ii Bobbio, Italy, it is important to recognize the hymns not only in terms of monastic development, but what they reveal about music. -

The First Life of Bernard of Clairvaux

CISTERCIAN FATHERS SERIES: NUMBER SEVENTY-SIX THE FIRST LIFE OF BERNARD OF CLAIRVAUX CISTERCIAN FATHERS SERIES: NUMBER SEVENTY-SIX The First Life of Bernard of Clairvaux by William of Saint-Thierry, Arnold of Bonneval, and Geoffrey of Auxerre Translated by Hilary Costello, OCSO Cistercian Publications www.cistercianpublications.org LITURGICAL PRESS Collegeville, Minnesota www.litpress.org A Cistercian Publications title published by Liturgical Press Cistercian Publications Editorial Offices 161 Grosvenor Street Athens, Ohio 45701 www.cistercianpublications.org In the absence of a critical edition of Recension B of the Vita Prima Sancti Bernardi, this translation is based on Mount Saint Bernard MS 1, with section numbers inserted from the critical edition of Recension A (Vita Prima Sancti Bernardi Claraevallis Abbatis, Liber Primus, ed. Paul Verdeyen, CCCM 89B [Turnhout: Brepols Publishers, 2011]). Scripture texts in this work are translated by the translator of the text. The image of Saint Bernard on the cover is a miniature from Mount Saint Bernard Abbey, fol. 1, reprinted with permission from Mount Saint Bernard Abbey. © 2015 by Order of Saint Benedict, Collegeville, Minnesota. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form, by print, microfilm, microfiche, mechanical recording, photocopying, translation, or any other means, known or yet unknown, for any purpose except brief quotations in reviews, without the previous written permission of Liturgical Press, Saint John’s Abbey, PO Box 7500, College- ville, Minnesota 56321-7500. Printed in the United States of America. 123456789 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Vita prima Sancti Bernardi. English The first life of Bernard of Clairvaux / by William of Saint-Thierry, Arnold of Bonneval, and Geoffrey of Auxerre ; translated by Hilary Costello, OCSO. -

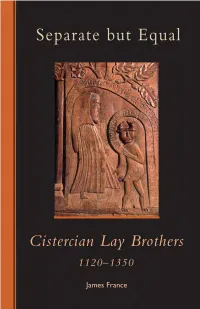

Separate but Equal: Cistercian Lay Brothers 1120-1350

All content available from the Liturgical Press website is protected by copyright and is owned or controlled by Liturgical Press. You may print or download to a local hard disk the e-book content for your personal and non-commercial use only equal to the number of copies purchased. Each reproduction must include the title and full copyright notice as it appears in the content. UNAUTHORIZED COPYING, REPRODUCTION, REPUBLISHING, UPLOADING, DOWNLOADING, DISTRIBUTION, POSTING, TRANS- MITTING OR DUPLICATING ANY OF THE MATERIAL IS PROHIB- ITED. ISBN: 978-0-87907-747-1 CISTERCIAN STUDIES SERIES: NUMBER TWO HUNDRED FORTY-SIX Separate but Equal Cistercian Lay Brothers 1120–1350 by James France Cistercian Publications www.cistercianpublications.org LITURGICAL PRESS Collegeville, Minnesota www.litpress.org A Cistercian Publications title published by Liturgical Press Cistercian Publications Editorial Offices Abbey of Gethsemani 3642 Monks Road Trappist, Kentucky 40051 www.cistercianpublications.org © 2012 by Order of Saint Benedict, Collegeville, Minnesota. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form, by print, microfilm, mi- crofiche, mechanical recording, photocopying, translation, or by any other means, known or yet unknown, for any purpose except brief quotations in reviews, without the previous written permission of Liturgical Press, Saint John’s Abbey, PO Box 7500, Collegeville, Minnesota 56321-7500. Printed in the United States of America. The Library of Congress has cataloged the printed edition as follows: Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data France, James. Separate but equal : Cistercian lay brothers, 1120-1350 / by James France. p cm. — (Cistercian studies series ; no. 246) Includes bibliographical references (p. -

(1) 2018, 39–51 Cisterian Water Systems and Their Significance for Shaping Landscape

Acta Sci. Pol. Formatio Circumiectus 17 (1) 2018, 39–51 ENVIRONMENTAL PROCESSES www.formatiocircumiectus.actapol.net/pl/ ISSN 1644-0765 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.15576/ASP.FC/2018.17.1.39 ORIGINAL PAPER Accepted: 1.03.2018 CISTERIAN WATER SYSTEMS AND THEIR SIGNIFICANCE FOR SHAPING LANDSCAPE Małgorzata Milecka Department of Landscape Design and Conservation, Faculty of Horticulture and Landscape Architecture, University of Life Sciences in Lublin, ul. Głęboka 28, 20-612 Lublin ABSTRACT Locating monasteries in river valleys with a considerable tributary system is regarded to be one of the rules for establishing Cistercian foundations: Bernardus valles, colles Benedictus amabat, Franciscus vicos, ma- gnas Dominicus urbes. A river valley provided opportunity for spatial development and land cultivation on fertile ground, something that Cistercian monks specialized in. In their efforts to raise effectiveness of their production, they did not underestimate the importance of water, not only by developing their fishing ponds, but also making water the main driving force for water mills and fulling mills, thereby promoting modern rural ‘food’ industry such as distilleries, breweries and open-pan salt production. In today’s post-cistercian landscape, in spite of many centuries of economic landscape exploitation, we can still discover properly func- tioning natural systems and traces of comprehensively developed water systems. Using the solutions utilized in monasteries all around Europe, the Order managed to enrich and shape landscape in a very considerable and unique way, not only on economic and social, but ecological level, too. Keywords: Cistercians, monastery, valley, water management, cultural landscape INTRODUCTION – CISTERCIANS AND THEIR ROLE Cistercians – today the phenomenon is referred to as IN THE DEVELOPMENT OF EUROPE’S LANDSCAPES melioratio terrae. -

A Life of Our Holy Father Norbert

A Life of Our Holy Father Norbert Early life and Conversion The members of the court of Henry V would have been astonished, had it been foretold, that one from amongst them would become a great Saint. That after a conversion of an unusual nature, followed by the austere penance and constant prayer, journeys over wide stretches of country to evangelise and reform both clergy and people, he would found a religious order, which would spread over the face of the earth, exceeding all expectations. Norbert of Xanten, the gifted courtier, gave little or no indication that he ever would become an apostle of Christ. He was a son of Heribert, Count of Gennep and claimed on both his father’s and his mother’s side to be of royal blood. He spent several years of his youth at the court of Frederic de Carinthia, Archbishop of Cologne. He was ordained sub-deacon and appointed to a Canonry in the Collegiate Church at Xanten. Later he left the Archbishop’s court and became attached to that of the Emperor Henry V. In a short space of time he grew to be as much a favourite here as he had been at the court of the Archbishop. In appearance he was attractive; in manners charming; in conversation interesting, in disposition, kind, thoughtful, considerate towards others; and thus it came about that members of the household from the highest to the lowest felt that in Norbert they had a sympathetic friend. The attractions of the court held him captive to such a degree that he neglected the religious duties, which his appointment to the Canonry of Xanten required of him. -

First Fruits Month of the Immaculate• Heart of Mary, August 2021 / Issue 53

The Norbertine Canonesses of the Bethlehem Priory of St. Joseph First Fruits Month of the Immaculate• Heart of Mary, August 2021 / Issue 53 “You nourished Your people With food of Angels... — Wisdom 16:20 Year of St. Joseph & Year of the Family 900th Jubilee Year of the Norbertine Order — 1121-2021 Dear Confreres, Family and Friends of the Bethlehem Priory, “You nourished Your people with food of angels... To Show Forth His Splendor that Your sons whom You loved might learn, O Lord, that it is not the various kinds of fruits that nourish man, Premonstratensians & the Eucharist but it is Your Word that preserves those who believe in You.” — Wisdom 16:20 & 26 In his lifetime, St. Norbert proved himself an Apostle of the During his life, our Holy Father St. Norbert was able to accomplish Eucharist by his great devotion to, reverence for and deep faith in very great things: from his intense personal austerity and love for God, the Real Presence of Christ in the Blessed Sacrament. frequent exorcisms, miracles of healing and prophecy, to the conversion When the Real Presence was doubted, disbelieved and challenged of pagan peoples, to the overcoming of heresy, and the founding of a in the 16th century, the intercession of St. Norbert was invoked, and religious order that had numerous monasteries by the time of his death. images emerged in which a monstrance, the vessel used to display As the Vita Norberti B states, it was through St. Norbert’s faith that he was the Consecrated Host at adoration, was placed in his hands. -

900 Newsletter1

NORBERTINES @ 900 Order of Canons Regular of Prémontré | Santa Maria de la Vid Abbey 14-Month Jubilee 900 YEARS An event as big as the 900th anni- versary of the founding of the Order of Prémontré deserves more than a mere one year celebration. The Order TOGETHER kicks off its jubilee celebration in NOVEMBER 2020 November. Norbert of Xanten Norbert’s conversion took place in the early 12th century when he was thrown from his horse. His life was never the same and it changed the lives men and women who would become Norbertines. Questions for Norbert Contemporary Norbertines, includ- ing Abbot Joel Garner and Prior Emeritus Eugene Gries, pose hypo- thetical questions to the founder of the Order of Prémontré. What would you like to ask Norbert of Xanten? Norbertine Impact Though not as well known as some of the larger Roman Catholic religious orders, Norbertines have impacted the world with ministerial work in parishes, schools, hospitals, and other areas. Man on Fire Many people have never heard of Norbert of Xanten. Former St. Norbert College President Thomas Kunkel changes some of this in his award-winning biography of Norbert titled Man on Fire. Norbertines @ 900 14-MONTH JUBILEE “A time to celebrate with gusto!” his November marks the start of That Norbertine life has been around Ta 14-month jubilee celebrating the 900 years “means we have been faithful 900th anniversary of a Roman Catholic to our charism,” says Father Chrysostom order started by Norbert of Xanten, Baer, prior of St. Michael’s Abbey in who established the fi rst Norbertine Silverado, California. -

Corpus Christi

Sacred Heart Catholic Church Mission: We are a dynamic and welcoming Catholic community, cooperating with God’s grace for the salvation of souls, serving those in need, and spreading the Good News of Jesus and His Love. Iglesia del Sagrado Corazón Misión: somos una comunidad católica dinámica y acogedora, cooperando con la gracia de Dios para la salvación de las almas, sirviendo a aque- llos en necesidad, y compartiendo la Buena Nueva de Jesús y Su amor. Pastoral Team Pastor: Rev. Fr. Michael Niemczak Deacons: Rev. Mr. Juan A. Rodríguez Rev. Mr. Michael Rowley Masses/Misas Monday: 5:30p.m. Tuesday: No Mass Wednesday: 12:10p.m. Thursday/jueves: 5:30p.m. (Spanish / en español) Friday: 12:10p.m. Saturday/sábado: (Vigil/vigilia) 6:00p.m. (Spanish / en español) Sunday: 8:30a.m., 10:30a.m. & 5:00p.m. At this time, we will be authorized 200 parishioners per Mass in the church. Hasta nuevo aviso, solo podemos tener 200 feligreses dentro de la iglesia por cada Misa. Church Address/dirección 921 N. Merriwether St. Clovis, N.M. 88101 Phone/teléfono: (575)763-6947 June 6th, 2021 / 6 de junio, 2021 Fax: (575)762-5557 Email: Corpus Christi [email protected] [email protected] Confession Times/ Eucharistic Adoration/ Website: www.sacredheartclovis.com Confesiones Adoración del Santísimo facebook: Mon. & Thurs./lunes y jueves Thursday / jueves www.facebook.com/sacredheartclovis 4:45p.m. - 5:20p.m. 12:00p.m. to 5:15p.m. Food Pantry/Despensa: Wed. & Fri./miércoles y viernes Friday / viernes 2nd & 4th Saturday/2˚ y 4˚ sábado: 11:30a.m. -

John Capgrave's the Life of St. Norbert and Its Literary and Cultural Significance

W&M ScholarWorks Undergraduate Honors Theses Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 5-2010 Dangerous Sanctity: John Capgrave's The Life of St. Norbert and its Literary and Cultural Significance James C. Staples College of William and Mary Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/honorstheses Recommended Citation Staples, James C., "Dangerous Sanctity: John Capgrave's The Life of St. Norbert and its Literary and Cultural Significance" (2010). Undergraduate Honors Theses. Paper 697. https://scholarworks.wm.edu/honorstheses/697 This Honors Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Undergraduate Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Dangerous Sanctity: John Capgrave’s The Life of St. Norbert and its Literary and Cultural Significance A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Bachelors of Arts in English from The College of William and Mary by James C. Staples Accepted for ___________________________________ (Honors, High Honors, Highest Honors) ________________________________________ Monica Brzezinski Potkay , Director ________________________________________ John Conlee , Committee Chair ________________________________________ Erin Minear ________________________________________ George Greenia Williamsburg, VA April 29, 2010 1 Attacks on Capgrave as Author Are the works of John Capgrave worth studying? The critical tradition would presume no. The literary craft of Capgrave’s hagiographic and historical poetry and prose has not received the attention it deserves even as scholars have been reassessing his contributions to English political and literary culture. Capgrave, a member of the Friar Hermits of St. -

Cistercian Architecture and Medieval Society Brill’S Studies in Intellectual History

Cistercian Architecture and Medieval Society Brill’s Studies in Intellectual History General Editor Han van Ruler, Erasmus University Rotterdam Founded by Arjo Vanderjagt Editorial Board C.S. Celenza, Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore M. Colish, Yale University J.I. Israel, Institute for Advanced Study, Princeton A. Koba, University of Tokyo M. Mugnai, Scuola Normale Superiore, Pisa W. Otten, University of Chicago VOLUME 221 Brill’s Studies on Art, Art History, and Intellectual History General Editor Robert Zwijnenberg, Leiden University VOLUME 5 The titles published in this series are listed at brill.com/bsih Cistercian Architecture and Medieval Society By Maximilian Sternberg LEIDEN • BOSTON 2013 Cover illustration: Villelongue, north face of the sculpted capitals of the central group of columns in the south gallery of the cloister (photo: author). Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Sternberg, Maximilian, 1979– Cistercian architecture and medieval society / by Maximilian Sternberg. pages cm. — (Brill’s studies in intellectual history, ISSN 0920-8607 ; volume 221) (Brill’s studies on art, art history, and intellectual history ; volume 5) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-90-04-25180-9 (hardback : alk. paper) — ISBN 978-90-04-25181-6 (e-book) 1. Cistercian architecture. 2. Architecture and society—Europe—To 1500. 3. Civilization, Medieval. I. Title. NA4828.S74 2013 726’.7712—dc23 2013026160 This publication has been typeset in the multilingual “Brill” typeface. With over 5,100 characters covering Latin, IPA, Greek, and Cyrillic, this typeface is especially suitable for use in the humanities. For more information, please see www.brill.com/brill-typeface. ISSN 0920-8607 ISBN 978-90-04-25180-9 (hardback) ISBN 978-90-04-25181-6 (e-book) Copyright 2013 by Koninklijke Brill NV, Leiden, The Netherlands. -

Bernard of Clairvaux

BERNARD OF CLAIRVAUX Patron Saint of the Templar Order Introduction. Bernard, the founding abbot of Clairvaux Abbey in Burgundy, in the heart of France, was one of the most commanding church leaders in the first half of the twelfth century. He rose in prominence to become one of the greatest spiritual masters of all time, as well as leading the reforms that made the monastic orders of Western Europe powerful propagators of the Catholic faith. He crafted the rules of behavior for the Cistercian Order, which he used as the model for the rules governing the Templar Order. He helped heal the great split in the papal authority and was asked to preach the Second Crusade. His appeal sent vast armies on the road toward Jerusalem. In a lesser known contribution, he was influential in ending savage persecution in Germany toward the Jews. Bernard’s Early Life. He was born in Fontaines-les-Dijon in southeastern France in 1090. Bernard's family was of noble lineage, both on the side of his father, Tescelin, and on that of his mother, Aleth or Aletta, but his ancestry cannot be clearly traced beyond his proximate forebears. The third of seven children, six of whom were sons, Bernard as a boy attended the school of the secular canons of Saint-Vorles, where it is probable that he studied the subjects included in the medieval trivium. In 1107, the early death of his mother, to whom he was bound by a strong affective tie, began a critical period in his life. Of the four years that followed, little is known but what can be inferred from their issue. -

Glossary of Catholic and Norbertine Terms from Abbey to Xanten a Glossary of Catholic and Norbertine Terms

From Abbey to Xanten A Glossary of Catholic and Norbertine Terms From Abbey to Xanten A Glossary of Catholic and Norbertine Terms As part of our mission at St. Norbert College, we value the importance of communio, a centuries-old charism of the Order of Premonstratensians (more commonly known as the Norbertines). Communio is characterized by mutual esteem, trust, sincerity, faith and responsibility, and is lived through open dialogue, communication, consultation and collaboration. In order for everyone to effectively engage in this ongoing dialogue, it is important that we share some of the same vocabulary and understand the concepts that shape our values as an institution. Because the college community is composed of people from diverse faith traditions and spiritual perspectives, this glossary explains a number of terms and concepts from the Catholic and Norbertine traditions with which some may not be familiar. We offer it as a guide to help people avoid those awkward moments one can experience when entering a new community – a place where people can sometimes appear to be speaking in code. While the terms in this modest pamphlet are important, the definitions are limited and are best considered general indications of the meaning of the terms rather than a complete scholarly treatment. We hope you find this useful. If there are other terms or concepts you would like to learn more about that are not covered in this guide, please feel free to contact the associate vice president for mission & student affairs at 920-403-3014 or [email protected]. In the spirit of communio, The Staff of Mission & Student Affairs When a word in a definition appears in bold type, it indicates that the word is defined elsewhere in the glossary.