CAR Durmaz Analysing Quality of Place.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

COMMISSION of the EUROPEAN COMMUNITIES Brussels, 7.8.2003

COMMISSION OF THE EUROPEAN COMMUNITIES Brussels, 7.8.2003 SEC(2003) 849 COMMISSION STAFF WORKING PAPER ANNEXES TO the TEN Annual Report for the Year 2001 {COM(2003) 442 final} COMMISSION STAFF WORKING PAPER ANNEXES TO the TEN Annual Report for the Year 2001 Data and Factsheets The present Commission Staff Working Paper is intended to complementing the Trans- European Networks (TEN) Annual Report for the Year 2001 (COM(2002)344 final. It consists of ten annexes, each covering a particular information area, and providing extensive information and data reference on the implementation and financing of the TEN for Energy, Transport and Telecommunications. 2 INDEX Pages Annex I : List of abbreviations .....................................................................................................4 Annex II : Information on TEN-T Priority Projects ......................................................................6 Annex III : Community financial support for Trans-European Network Projects in the energy sector during the period from 1995 to 2001 (from the TEN-energy budget line) ......24 Annex IV Progress achieved on specific TEN-ISDN / Telecom projects from 1997 to 2001....36 Annex V: Community financial support in 2001 for the co-financing of actions related to Trans-European Network Projects in the energy sector .............................................58 Annex VI : TEN-Telecom projects financed in 2001 following the 2001 call for proposals .......61 Annex VII : TEN-T Projects/Studies financed in 2001 under Regulation 2236/95 -

Digital Intermediate

Digital Intermediate: (typically abbreviated to DI) is a motion picture finishing process which classically involves digitizing a motion picture and manipulating the color and other image characteristics. Josh Haynie SVP Operations, Efilm. Member of the Worldwide Deluxe Family Team Leader: Colorists, Production, Editorial, Data Management, Scanning/Recording, Quality Control, Restoration, Vault, Security, Facilities 13 Years with Efilm Over 500 Feature Films delivered since 2003 Traditional and emerging Post Production since 1991 [email protected] efilm.com 79 Worldwide Locations 6570+ Fulltime Employees 800+ Metadata Technicians 120+ System R+D Developers 30,000 DCP’s delivered per month 60,000 Digital Distribution deliveries per month Let us take a look at what we have completed and a glimpse of what are are working on… Complex Projects Overall Workflow Testing Location Services Dailies VFX Pulls/ Shots Marketing Assembly Grading Render HD/ Blue Ray HDR UHD Large Format Archiving Looks and LUT’s Lighting Room Colors Costumes Locations Aspect Ratios Arri Alexa Digital Camera 35mm Film Camera Canon 5D Digital Camera/SLR Arri 65 Digital Camera Sony F65 Digital Camera Go Pro Imax Film Camera Red Digital Camera Phantom Digital Camera Canon C300 Digital Camera IPhone 6S Black Magic Digital Camera EC3: Hollywood, Location, Near Set, WW Receive, Archive and Verify Data Grade and QC each day’s footage Create Editorial Media daily Create and Distribute Studio Screening elements daily On Set Near Set Dailies Deliverables H.264 Network Deliverable Transfer Station Camera Mag Editorial Dailies Processing Colorstream NAS Storage Audio ARRI RAW Multiple LTO EC3 Archive DeBayered SAN Storage Backup I/O Station Controller Meta Data VFX Pulls Pulling frames for VFX creation during shoot Post shoot frame pulling for VFX creation. -

Cologix Montreal: Metro Connect Services Convenient, Simple Solution to Increase Access Across Data Centres Within a Metro Market

Cologix Montreal: Metro Connect Services Convenient, simple solution to increase access across data centres within a metro market Cologix’s Metro Connect is a low-cost product offering that extends Cologix’s dense network availability to customers regardless of data centre location within a market. Metro Connect is a fibre-based service that offers bandwidth of 100Mb (FastE), 1000Mb (GigE), or 10G and higher (Passive Wave). FastE and GigE services are delivered through a Cologix switch to the customer via a copper cross-connect. The Passive Wave offering provides a dedicated lambda over Cologix fibre that customers must light with their own network equipment. Customers are able to request one of two diverse routes for all three services. Cologix Montreal Metro Connect enables: Connections between Extended carrier and network A low-cost alternative to local Cologix’s 7 Montreal data choice loops centres Cologix’s Montreal Metro Connect product provides connections between the MTL1, Quick Facts: MTL2, MTL3, MTL4, MTL5, MTL6 and MTL7 data centres over shared dark fibre and Cologix-operated network equipment. The product comes in several different • Cologix operates confgurations to solve various customer requirements. All Metro Connect services include approx. 100,000 SQF across 7 a cross-connect within each facility to provide a complete end-to-end service. Montreal data centres • 2 pairs of 40-channel Cologix Montreal Metro Connect Map DWDM Mux-Demuxes (working and protect) enable 40x100 Gbps between each facility = 4Tbps Metro Optical -

Unclassified DSTI/ICCP(97)12/FINAL

Unclassified DSTI/ICCP(97)12/FINAL Organisation de Coopération et de Développement Economiques OLIS : 28-Jul-1998 Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development Dist. : 03-Aug-1998 __________________________________________________________________________________________ English text only Unclassified DSTI/ICCP(97)12/FINAL DIRECTORATE FOR SCIENCE, TECHNOLOGY AND INDUSTRY COMMITTEE FOR INFORMATION, COMPUTER AND COMMUNICATIONS POLICY OECD WORKSHOPS ON THE ECONOMICS OF THE INFORMATION SOCIETY WORKSHOP No. 6 London, 19-20 March 1997 English text English only 67862 Document complet disponible sur OLIS dans son format d'origine Complete document available on OLIS in its original format DSTI/ICCP(97)12/FINAL FOREWORD The OECD Workshops on the Economics of the Information Society are aimed at developing economic data, research and analysis in the area of “Global Information Infrastructure -- Global Information Society.” They are conducted under the aegis and direction of the ICCP Committee as the precursor for policy discussions within the Committee. The workshops concentrate on providing leading edge research on the economics of the coming “information society”, will have a quantitative and empirical focus and identify and refine the analytical and statistical tools needed for dealing with these issues. The sixth in the series of Workshops was held in London on the 19 and 20 March 1997 on the theme of “Market Competition and Innovation in the Information Society.” The Workshop was co- organised by the Science Policy Research Unit (SPRU) of the University of Sussex, UK, and the Institution of Electrical Engineers (IEE), together with the European Commission and the OECD. Overall co-ordination of the workshop was carried out by SPRU. -

Public Document Pack

Public Document Pack Committee Agenda City of Westminster Title: Environment Policy & Scrutiny Committee Meeting Date: Monday 19th January, 2015 Time: 7.00 pm Venue: Rooms 5, 6 & 7 - 17th Floor, City Hall Members: Councillors: Ian Adams (Chairman) Thomas Crockett Jonthan Glanz Louise Hyams Vincenzo Rampulla Karen Scarborough Cameron Thomson Jason Williams Members of the public are welcome to attend the meeting and listen to the discussion Part 1 of the Agenda Admission to the public gallery is by ticket, issued from the ground floor reception at City Hall from 6.00pm. If you have a disability and require any special assistance please contact the Committee Officer (details listed below) in advance of the meeting. An In duction loop operates to enhance sound for anyone wearing a hearing aid or using a transmitter. If you require T any further information, please contact the Committee Officer, Jonathan Deacon, Senior Committee and Governance Officer. Tel: 020 7641 2783; email: [email protected] Corporate Website: www.westminster.gov.uk Note for Members: Members are reminded that Officer contacts are shown at the end of each report and Members are welcome to raise questions in advance of the meeting. With regard to item 2, guidance on declarations of interests is included in the Code of Governance; if Members and Officers have any particular questions they should contact the Head of Legal & Democratic Services in advance of the meeting please. AGENDA PART 1 (IN PUBLIC) 1. MEMBERSHIP To note any changes to the membership. 2. DECLARATIONS OF INTEREST To receive declarations by Members and Officers of the existence and nature of any personal or prejudicial interests in matters on this agenda. -

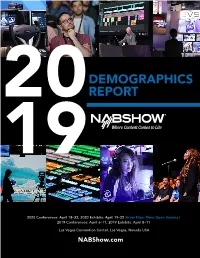

Attendee Demographics

DEMOGRAPHICS 20REPORT 19 2020 Conferences: April 18–22, 2020 Exhibits: April 19–22 Show Floor Now Open Sunday! 2019 Conferences: April 6–11, 2019 Exhibits: April 8–11 Las Vegas Convention Center, Las Vegas, Nevada USA NABShow.com ATTENDANCE HIGHLIGHTS OVERVIEW 27% 63,331 Exhibitors BUYERS 4% Other 24,896 91,921 TOTAL EXHIBITORS 69% TOTAL NAB SHOW REGISTRANTS Buyers Includes BEA registrations 24,086 INTERNATIONAL NAB SHOW REGISTRANTS from 160+ COUNTRIES 1,635* 963,411* 1,361 EXHIBITING NET SQ. FT. PRESS COMPANIES 89,503 m2 *Includes unique companies on the Exhibit Floor and those in Attractions, Pavilions, Meeting Rooms and Suites. 2019 NAB SHOW DEMOGRAPHICS REPORT PRIMARY BUSINESS Total Buyer Audience and Data Total Buyers: 63,331 ADVERTISING/PUBLIC RELATIONS/MARKETING 6% AUDIO PRODUCTION/POST-PRODUCTION SERVICE 21% BROADERCASTING/CARRIER 19% Cable/MSO Satellite (Radio or Television) Internet/Social Media Telco (Wireline/Wireless) Radio (Broadcast) Television (Broadcast) CONTENT/CHANNEL 8% Film/TV Studio Podcasting Independent Filmmaker Gaming Programming Network Photography DIGITAL MEDIA 4% DISTRIBUTOR/DEALER/RESELLER 4% EDUCATION 3% FAITH-BASED ORGANIZATION 1% FINANCIAL 1% HEALTHCARE/MEDICAL .4% SPORTS: TEAM/LEAGUE/VENUE 1% GOVERNMENT/NON-PROFIT 1% MANUFACTURER/SUPPLIER (HARDWARE) 3% PERFORMING ARTS/MUSIC/LIVE ENTERTAINMENT 1% RENTAL EQUIPMENT 1% SYSTEMS INTEGRATION 3% VIDEO PRODUCTION/POST-PRODUCTION 8% Video Production Services/Facility Video Post-Production Services/Facility WEB SERVICES/SOFTWARE MANUFACTURER 8% OTHER 7% 2019 NAB -

Preserving Moving Pictures and Sound

01000100 01010000 Preserving 01000011 Moving Pictures 01000100 and Sound 01010000 Richard Wright 01000011 01000100 DPC Technology Watch Report 12-01 March 2012 01010000 01000011 01000100 01010000 Series Series editors on behalf of the DPC 01000011 Charles Beagrie Ltd. Watch Principal Investigator for the Series 01000100 Neil Beagrie Technology 01010000 01000011DPC © Digital Preservation Coalition 2012 and Richard Wright 2012 Published in association with Charles Beagrie Ltd. ISSN: 2048-7916 http://dx.doi.org/10.7207/twr12-01 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing from the publisher. The moral right of the author has been asserted. First published in Great Britain in 2012 by the Digital Preservation Coalition. Foreword The Digital Preservation Coalition (DPC) is an advocate and catalyst for digital preservation, ensuring our members can deliver resilient long-term access to digital content and services. It is a not-for-profit membership organization whose primary objective is to raise awareness of the importance of the preservation of digital material and the attendant strategic, cultural and technological issues. It supports its members through knowledge exchange, capacity building, assurance, advocacy and partnership. The DPC’s vision is to make our digital memory accessible tomorrow. The DPC Technology Watch Reports identify, delineate, monitor and address topics that have a major bearing on ensuring our collected digital memory will be available tomorrow. They provide an advanced introduction in order to support those charged with ensuring a robust digital memory, and they are of general interest to a wide and international audience with interests in computing, information management, collections management and technology. -

Research White Paper

Research White Paper WHP 183 June 2010 High performance file transfer over IP networks Peter Brightwell BRITISH BROADCASTING CORPORATION BBC Research White Paper WHP 183 High performance file transfer over IP networks Peter Brightwell Abstract This White Paper outlines how broadcasters will increasingly need to transfer large amounts of content as files over IP networks. It examines some of the performance issues that can arise in typical scenarios, as well as other important aspects such as interoperability, security and management. It outlines some of the tools (both commercial and open source) that are available to help file transfers, and discusses what broadcasters should consider when making technology choices. This document was originally published in November 2009 in the EBU Technical Review (http://tech.ebu.ch/techreview). Additional key words: acceleration, authentication, bandwidth, BDP, buffer, congestion, connectivity, CIFS, cloud, delivery, despatch, dispatch, encryption, exchange, facility, firewall, FTP, GridFTP, HTTPS, Internet, latency, MDP, NAT, optimisation, packet loss, performance, prioritisation, protocol, resource allocation, rushes, scheduling, SCP, web service, SFTP, tapeless, TCP, throughput, TOE, tuning, UDP, verification, WAN, window White Papers are distributed freely on request. Authorisation of the Head of Broadcast/FM Research is required for publication. © BBC 2010. All rights reserved. Except as provided below, no part of this document may be reproduced in any material form (including photocopying or storing it in any medium by electronic means) without the prior written permission of BBC Future Media & Technology except in accordance with the provisions of the (UK) Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. The BBC grants permission to individuals and organisations to make copies of the entire document (including this copyright notice) for their own internal use. -

Economic Profile of Ontario's Computer Animation and Visual

Economic Profile of Ontario’s Computer Animation and Visual Effects Industry in 2014 Final Report June 2016 Prepared for: Prepared by: Nordicity Generously Supported by: Disclaimer: Funding for this study was provided by the Ontario Media Development Corporation. Any opinions, findings, conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Ontario Media Development Corporation or the Government of Ontario. The Government of Ontario and its agencies are in no way bound by the recommendations contained in this document. Economic Profile of Ontario’s Computer Animation and Visual Effects Industry in 2014 2 of 45 Table of Contents Executive Summary 4 1. Background 8 1.1 Project Mandate and Objectives 8 1.2 Approach and Methodology 8 2. Industry Profile 11 2.1 About the Computer Animation and Visual Effects Industry 11 2.2 Corporate Profile 12 3. Financial Profile 16 3.1 Financial Profile 16 3.2 Production Activity 21 3.3 Employment 23 3.4 Markets 25 4. Economic Impact Analysis 26 4.1 Direct Economic Impact 26 4.2 Industry Employment in FTEs 26 4.3 Spin-off and Total Economic Impact 27 5. Challenges and Opportunities 28 6. Case Studies 34 6.1 London: demand for talent exceeds supply 34 6.2 Montréal: strong ties with American and European markets 35 6.3 Vancouver: tax credits and talent attract international companies 37 6.4 Los Angeles: high salaries in an incredibly competitive market 39 6.5 New York: diverse scene driven by small, specialized studios 40 6.6 Relevance for Ontario 41 7. -

Analysis and Summary of Feasible Marketplace Business Models Covering All Trails

POSTMARK Project No: TP1388-17153 File Ref: 100907 Analysis and Summary of feasible marketplace business models covering all trails D4.4 Responsible Author: Matthew Addis Project Partner: IT Innovation POSTMARK PM-068-ITI-D4 4 feasible marketplace business models covering all trials V2_final.docx PROJECT DETAILS AND ACCESS Project Number: 17153-100907 Project Title: POSTMARK Deliverable Type: (PU/PP/RE/CO): PU Deliverable Number: D4.4 (V2) Contractual Date of Delivery: November 2012 Actual Date of Delivery: Title of deliverables: analysis and summary of feasible marketplace business models covering all trials Work-Package: WP4 (original) Nature of the Deliverable: (R, P, D, O): R Abstract: This report analyses the market for cloud services of the type that POSTMARK is pioneering including type, scale, readiness and barriers to adoption. The POSTMARK trials are reviewed in terms of the business benefits that the services offer, the validation of these by those involved in the trials, and the further work needed to move from trials to a fully commercial and production setting. Business benefits were wide ranging and included lowering costs, better meeting of deadlines, increase in volume of business, and improved customer service. Response from the trials was positive in all cases. This was echoed by the two public demonstration events hosted by the project in 2012 where the attendees (around 100 in total from the film and post communities) were positive about the services that POSTMARK is offering. The main barriers encountered were security, the need for high levels of availability and trust, the need for complete out-of-the box solutions, and of course concerns over cost. -

Demographics Report I 2 Geographic Breakdown Overview

DEMOGRAPHICS 20REPORT 19 2020 Conferences: April 18–22, 2020 Exhibits: April 19–22 Show Floor Now Open Sunday! 2019 Conferences: April 6–11, 2019 Exhibits: April 8–11 Las Vegas Convention Center, Las Vegas, Nevada USA NABShow.com ATTENDANCE HIGHLIGHTS OVERVIEW 27% 63,331 Exhibitors BUYERS 4% Other 24,896 91,921 TOTAL EXHIBITORS 69% TOTAL NAB SHOW REGISTRANTS Buyers Includes BEA registrations 24,086 INTERNATIONAL NAB SHOW REGISTRANTS from 160+ COUNTRIES Full demographic information on International Buyer Attendees on pages 7–9. 1,635* 963,411* 1,361 EXHIBITING NET SQ. FT. PRESS COMPANIES 89,503 m2 *Includes unique companies on the Exhibit Floor and those in Attractions, Pavilions, Meeting Rooms and Suites. 2019 NAB SHOW DEMOGRAPHICS REPORT I 2 GEOGRAPHIC BREAKDOWN OVERVIEW ALL 50 STATES REPRESENTED U.S. ATTENDEE BREAKDOWN 160+ COUNTRIES REPRESENTED 44% Pacific Region 19% Mountain Region 16% Central Region 21% New England/Mid and South Atlantic 24% 26% 30% NON-U.S. ATTENDEE BREAKDOWN 26% Europe 30% Asia 3% 24% N. America (excluding U.S.) 14% 3% 14% S. America 3% Australia 3% Africa 55 45 DELEGATIONS ENROLLED COUNTRIES REPRESENTED BY A DELEGATION COUNTRIESCOUNTRIES REPRESENTEDREPRESENTED Afghanistan Colombia Ethiopia Indonesia Pakistan Thailand Argentina Costa Rica France Ivory Coast Panama Tunisia Benin Democratic Republic Germany Japan Peru Turkey Brazil of Congo Ghana Mexico Russia Uruguay Burkina Faso Dominican Republic Greece Myanmar South Africa Venezuela Caribbean Nations Ecuador Guatemala New Zealand South Korea Chile Egypt Honduras -

G.Network to Invest Over £1Bn in London Broadband Rollout Following Successful Fundraise from USS and Cube Infrastructure Managers

Monday 14 December G.Network to invest over £1bn in London broadband rollout following successful fundraise from USS and Cube Infrastructure Managers ● Universities Superannuation Scheme Limited (“USS”) agrees to become a joint controlling shareholder and invest £295m of new equity in G.Network (the “Company”) ● Cube Infrastructure Managers (“Cube”) has invested in G.Network over the past two years extending its network to cover over 150,000 premises in central London and will remain as co-controlling shareholder alongside USS jointly to develop further G.Network. ● Debt facility of up to £745m secured from four banks, including extendable credit facility ● G.Network plans to roll out full fibre broadband to 1.4 million premises, reaching 13 London boroughs over five years ● Over 1,250 jobs expected to be created Full fibre broadband operator, G.Network, plans to invest over £1bn in rolling out connectivity in London following a successful fundraise. The fundraise includes a new equity investment by USS, the UK’s largest private pension scheme by way of assets, of up to £295m over 6 years in G.Network’s parent; as well as debt secured from four banks of up to £745m, contingent on passing certain milestones. G.Network digs streets to install brand new, state-of-the-art, contiguous full fibre broadband infrastructure in the capital, offering both residential and business customers ultra-fast speeds. The Company is building its network on an ‘Open Access’ principle, so that other providers can offer connections to their customers using G.Network infrastructure in future. G.Network is currently working with eight local authorities and will bring its rollout to a further five, aiming to connect at least 80% of premises in each.