Programmed Urban Forestry in Pittsburgh Began As Early As 1889

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Author: Stephan Bontrager, Director of Communications, Riverlife a Big Step Forward: Point State Park

Author: Stephan Bontrager, Director of Communications, Riverlife A Big Step Forward: Point State Park Pittsburgh’s riverfronts have undergone a long transformation from being used primarily for industry in the first half of the 20th century to the green public parks, trails, and facilities of today. The city’s riverbanks along its three rivers—the Allegheny, Monongahela and Ohio—are a patchwork quilt of publicly- and privately owned land, lined with industrial and transportation infrastructure that has created challenges for interconnected riverfront redevelopment across property lines. Despite the obstacles, Pittsburgh has seen a remarkable renaissance along its waterfronts. The city’s modern riverfront transformation began with the construction of Point State Park during the first “Pittsburgh Renaissance” movement of the 1940s and 50s by then- mayor David L. Lawrence. The 36-acre park at the confluence of Pittsburgh’s three rivers (the Allegheny, Monongahela and Ohio) was conceived as a transformational urban renewal project that would create public green space at the tip of the Pittsburgh peninsula. Championed by a bipartisan coalition of Lawrence, banker Richard King Mellon, and the Allegheny Conference on Community Development, Point State Park was created on land used primarily as a rail yard and acquired through eminent domain. Construction took several decades and the park was officially declared finished and opened to the public in 1974 with the debut of its signature feature, a 150-foot fountain at the westernmost tip of the park. After its opening, Point State Park saw near-constant use and subsequent deferred maintenance. In 2007 as part of the Pittsburgh 250th anniversary celebration, the park underwent a $35 million top-to-bottom renovation led by the Allegheny Conference, Riverlife, and the Department of Conservation and Natural Resources which owns and operates the park. -

Sheraden Homestead

HISTORIC REVIEW COMMISSION Division of Development Administration and Review City of Pittsburgh, Department of City Planning 200 Ross Street, Third Floor Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania 15219 INDIVIDUAL PROPERTY HISTORIC NOMINATION FORM Fee Schedule HRC Staff Use Only Please make check payable to Treasurer, City of Pittsburgh Date Received: ................................................ Individual Landmark Nomination: $100.00 Parcel No.: ...................................................... District Nomination: $250.00 Ward: .............................................................. Zoning Classification: ..................................... 1. HISTORIC NAME OF PROPERTY: Bldg. Inspector: ............................................... Council District: .............................................. Sheraden Homestead 2. CURRENT NAME OF PROPERTY: 2803 Bergman St. 3. LOCATION a. Street: 2803 Bergman St. b. City, State, Zip Code: Pittsburgh, Pa. 15204 c. Neighborhood: Sheraden 4. OWNERSHIP d. Owner(s): John G. Blakeley e. Street: 2803 Bergman St. f. City, State, Zip Code: Pittsburgh, Pa. 15204 Phone: () 5. CLASSIFICATION AND USE – Check all that apply Type Ownership Current Use: Structure Private – home Residential District Private – other Site Public – government Object Public - other Place of religious worship 1 6. NOMINATED BY: a. Name: Matthew W.C. Falcone b. Street: 1501 Reedsdale St., Suite 5003 c. City, State, Zip: Pittsburgh, Pa. 15233 d. Phone: (412) 256-8755 Email: [email protected] 7. DESCRIPTION Provide a narrative -

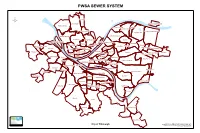

Pwsa Sewer System

PWSA SEWER SYSTEM ² Summer Hill Perry North Lincoln-Lemington-Belmar Brighton Heights Upper Lawrenceville Morningside Stanton Heights Northview Heights Lincoln-Lemington-Belmar Highland Park Marshall-Shadeland Central Lawrenceville Perry South Spring Hill-City View Garfield Marshall-Shadeland Troy Hill Esplen Lower Lawrenceville East Liberty Fineview Troy Hill California-Kirkbride Spring Garden Larimer Bloomfield Friendship Windgap Chartiers City Homewood West Central Northside R Polish Hill Sheraden E Homewood North Manchester IV East Allegheny R Y N E H Allegheny Center G Strip District Fairywood E Upper Hill Shadyside O L East Hills H Allegheny West L Homewood South IO A Bedford Dwellings R Chateau Point Breeze North IV E R Crafton Heights North Shore Middle Hill Elliott North Oakland Point Breeze Crawford-Roberts Terrace Village West End Squirrel Hill North Central Business District West Oakland Central Oakland Duquesne Heights South Shore Bluff Westwood HELA RIVER MONONGA South Oakland Ridgemont Regent Square Oakwood Squirrel Hill South Mount Washington Southside Flats East Carnegie Allentown Greenfield Southside Slopes Beltzhoover Swisshelm Park Arlington Heights Knoxville Arlington Beechview Banksville Mount Oliver Borough Hazelwood Mt. Oliver Bon Air St. Clair Glen Hazel Brookline Carrick Hays Overbrook New Homestead Lincoln Place Neither the City of Pittsburgh nor the PW&SA guarantees the accuracy of any of the information hereby made available, including but not limited to information concerning the location and condition of underground structures, and neither assumes any responsibility for any conclusions or interpretations made on the basis of such information. COP and PW&SA assume no Drawn By: JDS Date: 6/3/2016 City of Pittsburgh responsibility for any understanding or representations made by their agents or employees unless such understanding or representations are expressly set forth in a duly authorized written document, and such document expressly provides that responsibility therefore is assumed by the City or the PW&SA. -

2019 State of Downtown Pittsburgh

20 STATE OF DOWNTOWN PITTSBURGH19 TABLE OF CONTENTS For the past eight years, the Pittsburgh Downtown Partnership has been pleased to produce the State of Downtown Pittsburgh Report. This annual compilation and data analysis allows us to benchmark our progress, both year over year and in comparison to peer cities. In this year’s report, several significant trends came to light helping us identify unmet needs and better understand opportunities for developing programs and initiatives in direct response to those challenges. Although improvements to the built environment are evident in nearly every corridor of the Golden Triangle, significant resources are also being channeled into office property interiors to meet the demands of 21st century companies and attract a talented workforce to Pittsburgh’s urban core. More than $300M has been invested in Downtown’s commercial office stock over the 4 ACCOLADES AND BY THE NUMBERS last five years – a successful strategy drawing new tenants to Downtown and ensuring that our iconic buildings will continue to accommodate expanding businesses and emerging start-ups. OFFICE, EMPLOYMENT AND EDUCATION Downtown experienced a 31% growth in residential population over the last ten years, a trend that will continue with the opening 6 of hundreds of new units over the next couple of years. Businesses, from small boutiques to Fortune 500 companies, continued to invest in the Golden Triangle in 2018 while Downtown welcomed a record number of visitors and new residents. HOUSING AND POPULATION 12 Development in Downtown is evolving and all of these investments combine to drive the economic vitality of the city, making Downtown’s thriving renaissance even more robust. -

WEST PITTSBURGH Community Plan NRC Foreclosure Properties

WEST PITTSBURGH Community Plan NRC Foreclosure Properties Block & ZIP Month Lot Address Street Code Use Description Neighborhood Filing Date January 40-C-80 1234 EARLHAM ST 12805 Residential SINGLE FAMILY Crafton Heights 20090121 42-C-151 3312 RADCLIFFE ST 12005 Residential SINGLE FAMILY Esplen 20090122 42-S-267 2749 GLENMAWR ST 12005 Residential SINGLE FAMILY Sheraden 20090115 42-S-258 2769 GLENMAWR ST 12005 Residential SINGLE FAMILY Sheraden 20090115 42-N-250 1239 PRITCHARD ST 12005 Residential SINGLE FAMILY Sheraden 20090105 71-L-259 1470 HASS ST 12006 Residential SINGLE FAMILY Chartiers City 20090112 19-A-176 116 CEDARBROOK DR 12803 Residential SINGLE FAMILY Crafton Heights 20090121 21-K-24 2645 W CARSON ST 12060 Residential SINGLE FAMILY Esplen 20090115 21-N-4 2661 GLENMAWR ST 12005 Residential SINGLE FAMILY Sheraden 20090115 February 42-L-97 3117 BERGMAN ST 12005 Residential SINGLE FAMILY Sheraden 20090226 42-N-173 3154 CHARTIERS AVE 12005 Residential SINGLE FAMILY Sheraden 20090223 70-C-23 3408 CLEARFIELD ST 12802 Residential SINGLE FAMILY Windgap 20090217 71-B-293 3909 WINDGAP AVE 12802 Residential SINGLE FAMILY Windgap 20090211 20-R-2 728 RUDOLPH ST 12004 Residential SINGLE FAMILY Elliott 20090203 March 41-A-164 3011 BRISCOE ST 12004 Residential SINGLE FAMILY Sheraden 20090302 41-S-269 975 LOGUE ST 12804 Residential SINGLE FAMILY Crafton Heights 20090324 41-S-10 1036 WOODLOW ST 12804 Residential SINGLE FAMILY Crafton Heights 20090302 42-L-66 3036 BERGMAN ST 12005 Residential SINGLE FAMILY Sheraden 20090316 42-L-182 3135 LANDIS -

Social Services Activist Richard Garland Brings “Juice” to a New Program That Puts Ex-Cons on the Street to Stop Brutal Violence Before Lives Are Lost

Social services activist Richard Garland brings “juice” to a new program that puts ex-cons on the street to stop brutal violence before lives are lost. By Jim Davidson Photography by Steve Mellon Adrienne Young offers a cherished image of her son, Javon, gunned down a decade ago in the last epidemic of street violence involving youth in Pittsburgh. Young went on to found Tree of Hope, a faith-based agency that serves families and children devastated by senseless killings. 13 The story is familiar now. A dispute over turf, money, girls, pride or next to nothing is replayed again and again on the streets of Pittsburgh — streets now marked with the ferocity, the violence, the tragedy that can bring down a neighborhood when young people have guns. ❖ Adrienne Young knows about it all too well. On a night just before Christmas 10 years ago, her 18-year-old son, Javon Thompson, an artist who had just finished his first semester at Carnegie Mellon University, was visiting a friend’s apartment in East Liberty. “He was successful. He had never done anything to anyone. He was an artist and writer — he was a great child,” Young says now. That night, Benjamin Wright, a robber dressed in gang colors, burst into the apartment and icily ordered Thompson to “say his last words.” Gunshots rang out, killing Thompson and wounding two others. Wright, who later confessed that he shot Thompson and robbed him for failing to show proper respect to his Bloods street gang, is serving a life sentence. ❖ But the carnage from the violence extends well beyond the victims and the shooter. -

City of Pittsburgh Neighborhood Profiles Census 2010 Summary File 1 (Sf1) Data

CITY OF PITTSBURGH NEIGHBORHOOD PROFILES CENSUS 2010 SUMMARY FILE 1 (SF1) DATA PROGRAM IN URBAN AND REGIONAL ANALYSIS UNIVERSITY CENTER FOR SOCIAL AND URBAN RESEARCH UNIVERSITY OF PITTSBURGH JULY 2011 www.ucsur.pitt.edu About the University Center for Social and Urban Research (UCSUR) The University Center for Social and Urban Research (UCSUR) was established in 1972 to serve as a resource for researchers and educators interested in the basic and applied social and behavioral sciences. As a hub for interdisciplinary research and collaboration, UCSUR promotes a research agenda focused on the social, economic and health issues most relevant to our society. UCSUR maintains a permanent research infrastructure available to faculty and the community with the capacity to: (1) conduct all types of survey research, including complex web surveys; (2) carry out regional econometric modeling; (3) analyze qualitative data using state‐of‐the‐art computer methods, including web‐based studies; (4) obtain, format, and analyze spatial data; (5) acquire, manage, and analyze large secondary and administrative data sets including Census data; and (6) design and carry out descriptive, evaluation, and intervention studies. UCSUR plays a critical role in the development of new research projects through consultation with faculty investigators. The long‐term goals of UCSUR fall into three broad domains: (1) provide state‐of‐the‐art research and support services for investigators interested in interdisciplinary research in the behavioral, social, and clinical sciences; (2) develop nationally recognized research programs within the Center in a few selected areas; and (3) support the teaching mission of the University through graduate student, post‐ doctoral, and junior faculty mentoring, teaching courses on research methods in the social sciences, and providing research internships to undergraduate and graduate students. -

North Shore's Newest Development

NORTH SHORE’S NEWEST DEVELOPMENT NORTH SHORE DRIVE PITTSBURGH SAMPLE RENDERING SINCE ITS BEGINNING AS HOME TO THREE RIVERS STADIUM, THE NORTH SHORE HAS BECOME ONE OF PITTSBURGH’S MOST POPULAR ENTERTAINMENT DESTINATIONS. NOW HOME TO PNC PARK (PITTSBURGH PIRATES) AND HEINZ FIELD (PITTSBURGH STEELERS AND PITT PANTHERS), THE NORTH SHORE IS SO MUCH MORE THAN JUST GAME DAYS. DIRECTLY ADJACENT TO PNC PARK, THE NORTH SHORE’S NEWEST DEVELOPMENT WILL FEATURE STREET-LEVEL RETAIL SPACE WITH OFFICE AND RESIDENTIAL UNITS ABOVE AND AN ATTACHED PARKING STRUCTURE. COMING SOON NEW DEVELOPMENT Aerial View Site Plan Residential Entrance Gen. Tank Room Vestibule 101 110d COMING SOON Main Office Res. Corridor NEW Elec. 104 110c DEVELOPMENT Room 103 Trash Comp. 102 Egress Corridor Res. Mail 106 & Outdoor Storage Retail Loading Under Zone Res. Lobby Res. Lobby 105 110b Canopy 110a 114a Trash Room UP UP 107 Main Lobby 110 Transformer Rec. Retail Res. Office 100 Desk 113 Elev. Elev. Stair 1 Stair 2 ST-1 ST-2 Fire Comm. 112 Outdoor Retail Under Retail Project Name 109 Vestibule Canopy North Shore Lot 10 - 110e 113a Parking Garage Project Number 17021 H20 Service Client 111 Continental Real MOVE 1st Floor Estate Companies FACADE SOUTH for Drawing Title WHOLE DIMENSION #Layout Name Issue Date 1 1st Floor Sketch Number A-8 SCALE: 1/16" = 1'-0" A-8 Burgatory | North Shore Local Attractions Restaurants • gi-jin • Ruth’s Chris Steak House • The Eagle Beer & Food Hall • Sharp Edge Bistro • Gaucho’s • TGI Friday’s • The Foundry | Table & Tap • Ten Penny • Shorty’s Pins x Pints (coming soon) • The Terrace Room • The Speckled Egg • Talia • Tequila Cowboy • Vallozzi’s • Bar Louie • Andrew’s Steak and Seafood • Union Standard • Hyde Park Prime Steakhouse • Eddie V’s • Jerome Bettis 36 Grille • Braddock’s Rebellion • Wheelhouse Bar and Grill • Butcher and the Rye • Southern Tier Brewery • The Capital Grille • Burgatory • Eddie Merlot’s • Condado Tacos • Bridges & Bourbon • City Works • Fl. -

An Analysis of Housing Choice Voucher and Rapid Rehousing Programs in Allegheny County

Research Report Moving to Opportunity or Disadvantage? An Analysis of Housing Choice Voucher and Rapid Rehousing Programs in Allegheny County March 2020 The Allegheny County Department of Human Services One Smithfield Street Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania 15222 www.alleghenycountyanalytics.us Basic Needs | An Analysis of Housing Choice Voucher and Rapid Rehousing Programs in Allegheny County | March 2020 page 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS Executive Summary 3 Figures and Tables 5 Definitions 6 Acronyms 7 Introduction 7 Background 7 Methodology 11 Limitations 15 Analysis 15 Demographics of Rental Subsidy Participants 15 HCV Households by Level of Disadvantage (move-in date 2017) 16 RRH Households by Level of Disadvantage (move-in date 2017) 18 Insights from Both Programs 20 Subsidized Housing Distribution in City of Pittsburgh versus Suburban Census Tracts 22 County-Wide Distribution of Households Living in Areas of High or Extreme Disadvantage 24 Moving Patterns Among HCV Households over Time 26 Discussion and Next Steps 27 APPENDIX A: HCV and RRH Program Details 30 APPENDIX B: Community Disadvantage Indicators and Sources 32 APPENDIX C: Allegheny County Census Tracts by Level of Disadvantage 33 APPENDIX D: Allegheny County Census Tracts by Disadvantage with Municipal Borders and Labels 34 APPENDIX E: Allegheny County Census Tracts by Disadvantage with City of Pittsburgh Neighborhoods and Labels 35 www.alleghenycountyanalytics.us | The Allegheny County Department of Human Services Basic Needs | An Analysis of Housing Choice Voucher and Rapid Rehousing Programs in Allegheny County | March 2020 page 3 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Decades of social science research show that place has a profound influence on child-to-adult outcomes and this finding has far-reaching implications for how affordable housing policy should be designed and implemented. -

G2 West Busway-All Stops

G2 WEST BUSWAY-ALL STOPS MONDAY THROUGH FRIDAY SERVICE SATURDAY SERVICE To Downtown Pittsburgh To Carnegie To Downtown Pittsburgh To Carnegie Carnegie Carnegie Station Carnegie Bell Station Stop C Crafton Crafton Station Stop C Sheraden Sheraden Station Stop C South Shore WCarsonSt at Duquesne Incline Downtown Liberty Ave at SixthAve Downtown Liberty Ave at William Penn Pl Downtown Liberty Ave at William Penn Pl Downtown Seventh Ave at SmithfieldSt South Shore W Carson St opp. Duquesne Incline Sheraden Sheraden Station Stop A Crafton Crafton Station Stop A Carnegie Carnegie Station Carnegie Carnegie Station Carnegie Bell Station Stop C Crafton Crafton Station Stop C Sheraden Sheraden Station Stop C South Shore WCarsonSt at Duquesne Incline Downtown Liberty Ave at SixthAve Downtown Liberty Ave at William Penn Pl Downtown Liberty Ave at William Penn Pl Downtown Seventh Ave at SmithfieldSt South Shore W Carson St opp. Duquesne Incline Sheraden Sheraden Station Stop A Crafton Crafton Station Stop A Carnegie Carnegie Station 5:07 5:11 5:14 5:18 5:23 5:28 5:30 5:30 5:33 5:40 5:44 5:47 5:52 6:29 6:32 6:35 6:39 6:43 6:49 6:50 6:50 6:54 7:00 7:05 7:08 7:13 5:27 5:31 5:34 5:38 5:43 5:48 5:50 5:50 5:53 6:00 6:04 6:07 6:12 6:59 7:02 7:05 7:09 7:13 7:19 7:20 7:20 7:24 7:30 7:35 7:38 7:43 5:46 5:49 5:52 5:56 6:01 6:08 6:10 6:10 6:13 6:20 6:24 6:27 6:32 7:34 7:37 7:40 7:44 7:48 7:54 7:55 7:55 7:59 8:05 8:10 8:13 8:18 6:06 6:09 6:12 6:16 6:21 6:28 6:30 6:30 6:34 6:41 6:45 6:48 6:53 8:04 8:07 8:10 8:14 8:18 8:24 8:25 8:25 8:29 8:35 8:40 8:43 8:48 6:21 -

South Side Facts

SouthSouth SideSide FACTSFACTS Watch out! It’s hot! 65% of all glassware made in the United States came out of Pittsburgh Imagine liquid glass or liquid steel flow- and Allegheny County factories. ing like the Monongahela River—but at These factories produced all types of 3,100 degrees Fahrenheit! That's hot! glass: goblets, decanters, gas lamp- Years ago, glass, iron, and steel-making shades, window glass, bottles, and made the South Side famous throughout the nation and world. tableware. In the early 1800s, thousands of The basic ingredients of glass are South Siders worked in glass factories. By sand, potash (or soda), and lime. the 1880s, thousands more were working The sand for the first factory on the in iron and steel works. Although these South Side came from a sand bar industries have all but disappeared local- that used to be in the middle of the The Salvation Army building at Bingham ly, it is important to remember that these Monongahela River. Later, sand came Street and S. Ninth was once the United industries once fueled the South Side’s— from tributaries of the Allegheny and States Glass Company headquarters building. and Pittsburgh’s—growth and helped Monongahela Rivers: French Creek make this region the "Workshop of the and the Youghiogheny River. Potash is simply the ashes left after burning wood or World.” other plant material. Soda is crushed flint. Flint is one of the rocks in the hills of Pittsburgh. Limestone is a soft rock that is dug out of quarries and crushed to make lime, a powder-like substance. -

Syringe Exchange Service Mapping and Analysis with Neighborhood Level Factors Within Pittsburgh Pennsylvania

Syringe Exchange Service Mapping and Analysis with Neighborhood Level Factors within Pittsburgh Pennsylvania Samik Patel University of Pittsburgh Introduction Drug overdose accounts for over 50,000 deaths in the United States per year, with a death rate that has been steadily rising over the last two decades (Brown and Wehby, 2016). Deaths related to opioid overdoses from prescription drug opioids have had similar rising trends (Brown and Wehby, 2016). The opioid epidemic now involves illegal opioids such as heroin and illicitly manufactured fentanyl (O’Hara, 2016). The national trend for the opioid epidemic is displayed in Allegheny County, PA with a steady increase in overdose related deaths since 2006; an all-time high of 635 Allegheny County residents died from drug related overdoses in 2016 (Husley, 2016). The majority of these drug overdose related deaths involved opioids. It seems that this increased rate of opioid use would be correlated to an increased rate of drug injection. HCV (Hepatitis C), a blood borne infection, is most commonly transmitted through injection drug use and can survive in syringes for nearly a month after contamination. HCV poses a significant threat of outbreak, and as a result, syringe access programs, such as Prevention Point Pittsburgh (PPP) are imperative in minimizing infection and preventing outbreak (Allegheny City Council, 2008). PPP is currently the only syringe access program in Allegheny County. PPP engages in syringe exchange encounters that also include risk reduction education, referrals to additional services, and provision of sterile injection equipment. PPP collects a small amount of information from every client during a needle exchange through Exchanger Forms.