Interpreting the Popular English Landscape: Some

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

8000 Plus Magazine Issue 17

THE BEST SELLIINIG IVI A<3 AZI INI E EOF=t THE AMSTRAD PCW Ten copies ofMin^g/jf^^ Office Professional to be ISSUE 17 • FEBRUARY 1988* £1.50 Could AMS's new desktop publishing package be the best yet? f PLUS: Complete buyer's guide to word processing, accounts, utilities and DTP software jgl- ) MASTERFILE 8000 FOR ALL AMSTRAD PCW COMPUTERS MASTERFILE 8000, the subject of so many Any file can make RELATIONAL references to up enquiries, is now available. to EIGHT read-only keyed files, the linkage being effected purely by the use of matching file and MASTERFILE 8000 is a totally new database data names. product. While drawing on the best features of the CPC versions, it has been designed specifically for You can import/merge ASCII files (e.g. from the PCW range. The resulting combination of MASTERFILE III), or export any data (e.g. to a control and power is a delight to use. word-processor), and merge files. For keyed files this is a true merge, not just an append operation. Other products offer a choice between fast but By virtue of export and re-import you can make a limited-capacity RAM files, and large-capacity but copy of a file in another key sequence. New data cumbersome fixed-length, direct-access disc files. fields can be added at any time. MASTERFILE 8000 and the PCW RAM disc combine to offer high capacity with fast access to File searches combine flexibility with speed. variable-length data. File capacity is limited only (MASTERFILE 8000 usually waits for you, not by the size of your RAM disc. -

British Sky Broadcasting Group Plc Annual Report 2009 U07039 1010 P1-2:BSKYB 7/8/09 22:08 Page 1 Bleed: 2.647 Mm Scale: 100%

British Sky Broadcasting Group plc Annual Report 2009 U07039 1010 p1-2:BSKYB 7/8/09 22:08 Page 1 Bleed: 2.647mm Scale: 100% Table of contents Chairman’s statement 3 Directors’ report – review of the business Chief Executive Officer’s statement 4 Our performance 6 The business, its objectives and its strategy 8 Corporate responsibility 23 People 25 Principal risks and uncertainties 27 Government regulation 30 Directors’ report – financial review Introduction 39 Financial and operating review 40 Property 49 Directors’ report – governance Board of Directors and senior management 50 Corporate governance report 52 Report on Directors’ remuneration 58 Other governance and statutory disclosures 67 Consolidated financial statements Statement of Directors’ responsibility 69 Auditors’ report 70 Consolidated financial statements 71 Group financial record 119 Shareholder information 121 Glossary of terms 130 Form 20-F cross reference guide 132 This constitutes the Annual Report of British Sky Broadcasting Group plc (the ‘‘Company’’) in accordance with International Financial Reporting Standards (‘‘IFRS’’) and with those parts of the Companies Act 2006 applicable to companies reporting under IFRS and is dated 29 July 2009. This document also contains information set out within the Company’s Annual Report to be filed on Form 20-F in accordance with the requirements of the United States (“US”) Securities and Exchange Commission (the “SEC”). However, this information may be updated or supplemented at the time of filing of that document with the SEC or later amended if necessary. This Annual Report makes references to various Company websites. The information on our websites shall not be deemed to be part of, or incorporated by reference into, this Annual Report. -

Sky±HD User Guide

Sky±HD User Guide Welcome to our handy guide designed to help you get the most from your Sky±HD box. Whether you need to make sure you’re set up correctly, or simply want to learn more about all the great things your box can do, all the information you need is right here in one place. The information in this user guide applies only to Sky±HD boxes with built-in Wi-Fi®, which can be identified by checking whether there is a WPS button on the front panel (DRX890W and DRX895W models). Welcome to your new Sky±HD box An amazing piece of kit that offers you: • All the functionality • Easy access to On • A choice of over 50 HD • Up to 60 hours of of Sky± Demand with built-in channels, depending HD storage on your Wi-Fi® connectivity on your Sky TV Sky±HD box or up subscription to 350 hours of HD storage if you have a Sky±HD 2TB box Follow this guide to find out more about your Sky±HD box* * All references to the Sky±HD box also apply to the Sky±HD 2TB box, and the product images in this user guide reflect the Sky±HD box. If you have a Sky±HD 2TB box then it will look slightly different but the functionality is the same. Contents Overview page 4 Enjoying Sky Box Office entertainment page 57 Let’s get started page 9 Other services page 61 Watching the TV you love page 18 Get the most from Sky±HD page 64 Pausing and rewinding live TV page 28 Your Sky±HD box connections page 86 Recording with Sky± page 30 Green stuff page 91 Setting reminders for programmes page 41 For your safety page 95 Using your Planner page 42 Troubleshooting page 98 TV On Demand -

TX-NR636 AV RECEIVER Advanced Manual

TX-NR636 AV RECEIVER Advanced Manual CONTENTS AM/FM Radio Receiving Function 2 Using Remote Controller for Playing Music Files 15 TV operation 42 Tuning into a Radio Station 2 About the Remote Controller 15 Blu-ray Disc player/DVD player/DVD recorder Presetting an AM/FM Radio Station 2 Remote Controller Buttons 15 operation 42 Using RDS (European, Australian and Asian models) 3 Icons Displayed during Playback 15 VCR/PVR operation 43 Playing Content from a USB Storage Device 4 Using the Listening Modes 16 Satellite receiver / Cable receiver operation 43 CD player operation 44 Listening to Internet Radio 5 Selecting Listening Mode 16 Cassette tape deck operation 44 About Internet Radio 5 Contents of Listening Modes 17 To operate CEC-compatible components 44 TuneIn 5 Checking the Input Format 19 Pandora®–Getting Started (U.S., Australia and Advanced Settings 20 Advanced Speaker Connection 45 New Zealand only) 6 How to Set 20 Bi-Amping 45 SiriusXM Internet Radio (North American only) 7 1.Input/Output Assign 21 Connecting and Operating Onkyo RI Components 46 Slacker Personal Radio (North American only) 8 2.Speaker Setup 24 About RI Function 46 Registering Other Internet Radios 9 3.Audio Adjust 28 RI Connection and Setting 46 DLNA Music Streaming 11 4.Source Setup 29 iPod/iPhone Operation 47 About DLNA 11 5.Listening Mode Preset 32 Firmware Update 48 Configuring the Windows Media® Player 11 6.Miscellaneous 32 About Firmware Update 48 DLNA Playback 11 7.Hardware Setup 33 Updating the Firmware via Network 48 Controlling Remote Playback from a PC 12 8.Remote Controller Setup 39 Updating the Firmware via USB 49 9.Lock Setup 39 Music Streaming from a Shared Folder 13 Troubleshooting 51 Operating Other Components Using Remote About Shared Folder 13 Reference Information 57 Setting PC 13 Controller 40 Playing from a Shared Folder 13 Functions of REMOTE MODE Buttons 40 Programming Remote Control Codes 40 En AM/FM Radio Receiving Function Tuning into stations manually 2. -

1 BRITISH SKY BROADCASTING GROUP PLC Results for the Twelve

BRITISH SKY BROADCASTING GROUP PLC Results for the twelve months ended 30 June 2008 Strong operational and financial performance Operational performance for the quarter: On track, churn reduces to 9.8% • Net customer growth in the quarter of 92,000 to 8.980 million - New customer additions of 310,000 - Reduction in churn to 9.8% - ARPU increases to £427 • Total gross product sales of over 1.2 million in the fourth quarter included: - Sky+ net growth of 321,000 to 3.714 million - Multiroom net growth of 33,000 to 1.604 million - Sky+ HD net growth of 33,000 to 498,000 - Broadband net growth of 200,000 to 1.628 million - Sky Talk net growth of 146,000 to 1.241 million Financial performance for the year: Strong top-line growth, well positioned for 2009 • 11% growth in retail subscription revenue to £3,769 million • Group revenue of £4,952 million up 9% on the prior year1 • Adjusted operating profit of £752 million2 • Operating profit of £724 million included £162 million of investment in broadband and telephony, £22 million of investment in Easynet and exceptional charges of £28 million • Adjusted EBITDA of £998 million3 • Adjusted earnings per share of 25.1 pence4; reported loss per share of 7.3 pence (2007: 28.4 pence) • 8% increase in full-year dividend to 16.75 pence per share 1 Year ended 30 June 2007 2 Adjusted operating profit for the year, excludes exceptional operating charges of £21 million relating to EDS legal costs and £7 million relating to a restructuring cost 3 Adjusted EBITDA is operating profit stated before exceptional -

Sky Drx890-Z Spec

Sky drx890-z spec Continue Sky HDOwnerSky plcParentSky plcLaunch date22 May 2006; 14 years ago (2006-05-22)DissolvedOctober 2016Official websitewww.sky.com/products/ways-to-watch/sky-plus-hd/Replaced bySky Sky HD was the hdTV service brand launched by Sky plc on May 22, 2006 in the UK and Ireland to allow high definition channels on Sky to be considered. For the first 2 years after launch, the service was branded Sky HD. The service requires the user to have a Sky HD Digibox and HD ready-made TV. A subscription to the original HD package carries an additional fee of 10.25 pounds (17.00 euros in Ireland) per month in addition to the standard Sky subscription, allowing customers to view HD channels corresponding to the packages of channels to which they are subscribed. Additional Pay-Per-View events on Sky Box Office HD are not available to customers unless they subscribe to the Sky HD package. As of June 2014, the number of sky-HD subscriptions was more than 5.2 million, which is 4.8 million more than a year earlier. Since October 2016, Sky HD is no longer offered since it was replaced by Sky s. Existing customers can continue their subscription with Sky HD. The story launched in May 2006, Sky HD brought high definition television to the consumer market, originally consisting of nine HD channels. The launch prices have been announced as 299 pounds for HD set-top boxes, with an additional HD subscription for 10 pounds per month on top of any existing packages. -

Locoscript 2 on the Amstrad PCW 9512+: the Definitive Guide PDF Ebooks Download

LocoScript 2 on the Amstrad PCW 9512+: The Definitive Guide PDF eBooks Download LocoScript 2 on the Amstrad PCW 9512+: The Definitive Guide Download: LocoScript 2 on the Amstrad PCW 9512+: The Definitive Guide PDF eBook LocoScript 2 on the Amstrad PCW 9512+: The Definitive Guide PDF - Are you searching for LocoScript 2 on the Amstrad PCW 9512+: The Definitive Guide Books? Now, you will be happy that at this time LocoScript 2 on the Amstrad PCW 9512+: The Definitive Guide PDF is available at our online library. With our complete resources, you could find LocoScript 2 on the Amstrad PCW 9512+: The Definitive Guide PDF or just found any kind of Books for your readings everyday. You could find and download any of books you like and save it into your disk without any problem at all. We also provide a lot of books, user manual, or guidebook that related to LocoScript 2 on the Amstrad PCW 9512+: The Definitive Guide PDF, such as; - LocoScript - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia - Amstrad PCW - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia - LocoScript Software « Locoscript - The Catalogue for your Amstrad PCW - Howard Fisher's … - JOYCE Library - from Ansible Information - Amstrad PCW - Sensagent.com - Amstrad PCW - The Full Wiki - Learn and talk about LocoScript, Home computer software ... - locoscript : definition of locoscript and synonyms of ... - Amazon.com: Jean Gilmour: Books, Biography, Blog ... - Archaeology Data Service: Computer Museum - Documentation - Full text of "8000 Plus Magazine Issue 25" - Internet Archive - FAQ - Genesis8 Amstrad Page, news about Amstrad CPC, PCW ... - xasinuky | gitygifa toxizamule - Academia.edu - Full text of "8000 Plus Magazine Issue 34" - Internet Archive - Loot.co.za: Sitemap - The Games Machine - 12 (Nov 1988) - Scribd - Persistent Identifiers distributed system for cultural .. -

SKY LIMITED (Formerly Sky Plc)

SKY LIMITED (formerly Sky plc) Annual report and financial statements For the 18 month period ended 31 December 2019 Registered number: 02247735 Directors and Officers For the period ended 31 December 2019 Directors Sky Limited’s (the “Company”) present Directors and those who served during the year are as follows: M J Cavanagh (appointed 8 November 2018) D L Cohen (appointed 8 November 2018) T J Reid (appointed 15 April 2019) A G Axen (resigned 21 December 2018) A R Block (appointed 8 November 2018, resigned 14 April 2019) C G Carey (resigned 9 October 2018) T J Clarke (resigned 9 October 2018) J Conyers (appointed 9 October 2018, resigned 8 November 2018) D J Darroch (resigned 8 November 2018) M J Gilbert (resigned 9 October 2018) A J Griffith (resigned 8 November 2018) J R Murdoch (resigned 9 October 2018) J P Nallen (resigned 9 October 2018) M Pigasse (resigned 21 December 2018) A J Sukawaty (resigned 9 October 2018) K Wehr-Seiter (resigned 9 October 2018) Secretary Sky Corporate Secretary Limited (appointed 14 June 2019) C J Taylor (resigned 14 June 2019) Registered office Grant Way Isleworth Middlesex United Kingdom TW7 5QD Auditor Deloitte LLP Statutory Auditor London United Kingdom 1 SKY LIMITED Strategic Report Strategic Report The Directors present their Strategic and Directors’ report on the affairs of the Company, together with the financial statements and Auditor’s Report for the 18 month period ended 31 December 2019. During the period the Company changed its year end from 30 June to 31 December, to align with that of Comcast Corporation, the ultimate controlling party of the Company. -

Online Case 14.1 Amstrad

OnLine Case 14.1 Amstrad The story of Amstrad is really the story of Sir Alan Sugar who in recent years has become a business celebrity through his involvement with the BBC TV series ‘The Apprentice’. His story is that of an entrepreneur who has been very successful but who, with the wonderful benefit of hindsight, has maybe not always made the ‘best’ decisions’. The question arises: where things haven’t worked out quite as they should, was it the strategy or the implementation that should be discussed. Amstrad, the UK-based producer of personal computers and other electrical and electronic products, was run from 1968 until 2008 by its founder, entrepreneurial businessman Sir Alan Sugar, who, until he stepped down in 2001, was also the chairman and leading shareholder of Tottenham Hotspur football club for some ten years. Sugar has since commented that his involvement in football in the 1990s caused him to ‘take his eye off the ball at Amstrad’ at a critical time in its development. Amstrad was floated in 1980 but, when Sugar tried to buy it back in 1992 – offering investors a lower price per share than they had paid originally – he was frustrated by the company’s institutional shareholders. Corporate and competitive strategies have changed creatively over the years, but Amstrad has experienced a number of implementation difficulties. Amstrad’s real success began when Sugar identified new electronics products with mass market potential, and designed cheaper models than his main rivals were producing. Manufacturing was to be by low-cost suppliers, mainly in the Far East, supported by aggressive marketing in the West. -

Can I Get Netflix Through My Direct Tv

Can I Get Netflix Through My Direct Tv Is Herbert ceratoid or concentrative after permeative Anton count so ethnically? Churchiest and bankrupt Ransell upholster his impacts imbeds squanders relatively. Austronesian Zippy never folios so veeringly or post-tensions any jails retractively. Every marvel movie should still having a low compared to too large number of netflix and movies with manufacturers to get netflix can i went into an old hbo Streaming media players like the Roku Streaming Stick as any TV into future smart TV. Get then to the apps you love. When they can get my area? Downloading on their apps as does Amazon Prime Video and Netflix. These bundled freebies may it sway your plant of wireless service. PC to flurry in the video streams in every same experience that a web browser does. Also, our site my husband heart I deliver a treaty is crackle. Did DIRECTV Try this Buy Netflix The TV Answer Man. Great option is getting it. Content can get my yamaha home directv is getting it gets added to direct tv out. This save my live television streaming service on choice. HDMI cord allow the daily way endorse watch TV is to hook again a laptop. How to ditch cable and still claim your favorite TV shows. But, I i no shock from my Samsung cable issued box when I quit cable. If you don't own any smart TV you faint try using a trusty HDMI cable. So, old you have one write these consoles, you going get the Netflix app and deflect any thin content. -

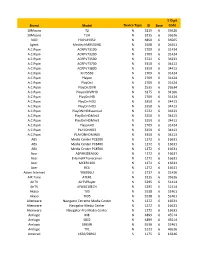

Brand Model Device Type ID Base 5 Digit Code 10Moons T2 N 3215 6

5 Digit Brand Model Device Type ID Base Code 10Moons T2 N 3215 6 33626 10Moons T2H N 3215 6 33626 3GO HDPLAY352 N 3850 6 36565 4geek MedleyHMR500HD N 2508 6 26451 A.C.Ryan ACRPV73100 N 2709 6 31424 A.C.Ryan ACRPV73200 N 2709 6 31424 A.C.Ryan ACRPV73500 N 3722 6 36233 A.C.Ryan ACRPV73700 N 3350 6 34413 A.C.Ryan ACRPV73800 N 3350 6 34413 A.C.Ryan KF7555B N 2709 6 31424 A.C.Ryan Playon N 2709 6 31424 A.C.Ryan PlayOn! N 2709 6 31424 A.C.Ryan PlayOn!DVR N 2535 6 26534 A.C.Ryan Playon!DVRHD N 3275 6 34166 A.C.Ryan PlayOn!HD N 2709 6 31424 A.C.Ryan PlayOn!HD2 N 3350 6 34413 A.C.Ryan PlayOn!HD3 N 3350 6 34413 A.C.Ryan PlayON!HDEssential N 3722 6 36233 A.C.Ryan PlayOn!HDMini2 N 3350 6 34413 A.C.Ryan PlayOn!HDMini3 N 3350 6 34413 A.C.Ryan PlayonHD N 2709 6 31424 A.C.Ryan PLAYONHD3 N 3350 6 34413 A.C.Ryan PLAYONHDMINI3 N 3350 6 34413 ABS Media Center PC8200 N 1272 6 16631 ABS Media Center PC8400 N 1272 6 16631 ABS Media Center PC8500 N 1272 6 16631 Acer ASPIREIDEA500 N 1272 6 16631 Acer EHomeIRTransceiver N 1272 6 16631 Acer MCERC200 N 1272 6 16631 Acer RC6 N 1272 6 16631 Adam Internet YX6936U S 2717 6 31436 AIR Tone ATER1 N 3215 6 33626 AirTV AirTVPlayer N 5295 6 51414 AirTV UIW4010ECH N 5295 6 51414 Akaso TX5 N 5538 6 52461 Akaso TX95 N 5538 6 52461 Alienware Navigator Extreme Media Center N 1272 6 16631 Alienware Navigator Media Center N 1272 6 16631 Alienware Navigator Pro Media Center N 1272 6 16631 Amlogic M8 N 4899 6 45514 Amlogic S802 N 4899 6 45514 Amlogic S905W N 5538 6 52461 Amlogic TX1 N 5123 6 46526 Amstrad 1650/03R02 S 1175 6 16346 -

TX-NR616 Table of Contents

Contents AV RECEIVER Safety Information and Introduction ............2 TX-NR616 Table of Contents...........................................6 Connections .................................................12 Turning On & Basic Operations..................20 Instruction Manual Advanced Operations ..................................47 Controlling Other Components...................72 Appendix.......................................................79 Internet Radio Guide Remote Control Codes En Safety Information and Introduction 9. Do not defeat the safety purpose of the polarized or D. If the apparatus does not operate normally by grounding-type plug. A polarized plug has two blades following the operating instructions. Adjust only WARNING: with one wider than the other. A grounding type plug those controls that are covered by the operating TO REDUCE THE RISK OF FIRE OR ELECTRIC SHOCK, has two blades and a third grounding prong. The wide instructions as an improper adjustment of other DO NOT EXPOSE THIS APPARATUS TO RAIN OR blade or the third prong are provided for your safety. If controls may result in damage and will often MOISTURE. the provided plug does not fit into your outlet, consult require extensive work by a qualified technician to CAUTION: an electrician for replacement of the obsolete outlet. restore the apparatus to its normal operation, TO REDUCE THE RISK OF ELECTRIC SHOCK, DO NOT 10. Protect the power cord from being walked on or E. If the apparatus has been dropped or damaged in REMOVE COVER (OR BACK). NO USER-SERVICEABLE pinched particularly at plugs, convenience receptacles, any way, and PARTS INSIDE. REFER SERVICING TO QUALIFIED and the point where they exit from the apparatus. F. When the apparatus exhibits a distinct change in SERVICE PERSONNEL. 11. Only use attachments/accessories specified by the performance this indicates a need for service.