Needs Assessment Report South-West Region Cameroon July

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mountain Resources Expliotation For

International Journal of Geography and Régional Planning Research Vol.1,No.1,pp.1-12, March 2014 Published by European Centre for Research Training and Development UK (www.eajournals.org) MONTANE RESOURCES EXPLOITATION AND THE EMERGENCE OF GENDER ISSUES IN SANTA ECONOMY OF THE WESTERN BAMBOUTOS HIGHLANDS, CAMEROON Zephania Nji FOGWE Department of Geography, Box 3132, F.L.S.S., University of Douala ABSTRACT: Highlands have played key roles in the survival history of humankind. They are refuge heavens of valuable resources like fresh water endemic floral and faunal sanctuaries and other ecological imprints. The mountain resource base in most tropical Africa has been mined rather than managed for the benefit of the low-lying areas. The world over an appreciable population derives its sustenance directly from mountain resources and this makes for about one-tenth of the world’s poorest.The Western highlands of Cameroon are an archetypical territory of a high population density and an economically very active population. The highlands are characterised by an ecological fragility and a multi-faceted socio-economic dynamism at varied levels of poverty, malnutrition and under employment, yet about 80 percent of the Santa highlands’ population depends on its natural resource base of vast fertile land, fresh water and montane refuge forest for their livelihood. KEYWORDS: Montane Resources, Gender Issues, Santa Economy, Western Bamboutos, Cameroon INTRODUCTION The volcanic landscape on the western slopes of the Bamboutos mountain range slopes to the Santa Highlands is an area where agriculture in the form of crop production and animal rearing thrives with remarkable success. Arabica coffee cultivation was in extensive hectares cultivated at altitudes of about 1700m at the Santa Coffee Estate at Mile 12 in the 1970s and 1980s. -

Full Text Article

SJIF Impact Factor: 3.458 WORLD JOURNAL OF ADVANCE ISSN: 2457-0400 Alvine et al. PageVolume: 1 of 3.21 HEALTHCARE RESEARCH Issue: 4. Page N. 07-21 Year: 2019 Original Article www.wjahr.com ASSESSING THE QUALITY OF LIFE IN TOOTHLESS ADULTS IN NDÉ DIVISION (WEST-CAMEROON) Alvine Tchabong1, Anselme Michel Yawat Djogang2,3*, Michael Ashu Agbor1, Serge Honoré Tchoukoua1,2,3, Jean-Paul Sekele Isouradi-Bourley4 and Hubert Ntumba Mulumba4 1School of Pharmacy, Higher Institute of Health Sciences, Université des Montagnes; Bangangté, Cameroon. 2School of Pharmacy, Higher Institute of Health Sciences, Université des Montagnes; Bangangté, Cameroon. 3Laboratory of Microbiology, Université des Montagnes Teaching Hospital; Bangangté, Cameroon. 4Service of Prosthodontics and Orthodontics, Department of Dental Medicine, University of Kinshasa, Kinshasa, Democratic Republic of Congo. Received date: 29 April 2019 Revised date: 19 May 2019 Accepted date: 09 June 2019 *Corresponding author: Anselme Michel Yawat Djogang School of Pharmacy, Higher Institute of Health Sciences, Université des Montagnes; Bangangté, Cameroon ABSTRACT Oral health is essential for the general condition and quality of life. Loss of oral function may be due to tooth loss, which can affect the quality of life of an individual. The aim of our study was to evaluate the quality of life in toothless adults in Ndé division. A total of 1054 edentulous subjects (partial, mixed, total) completed the OHIP-14 questionnaire, used for assessing the quality of life in edentulous patients. Males (63%), were more dominant and the ages of the patients ranged between 18 to 120 years old. Caries (71.6%), were the leading cause of tooth loss followed by poor oral hygiene (63.15%) and the consequence being the loss of aesthetics at 56.6%. -

Africanprogramme for Onchocerctasts Control (Apoc)

RESERVED FOR PROTECT LOGO/HEADING COUNTRYAIOTF: CAMEROON Proiect Name: CDTI SW 2 Approval vearz 1999 Launchins vegr: 2000 Renortins Period: From: JANUARY 2008 To: DECEMBER 2008 (Month/Year) ( Mont!{eq) Proiectvearofthisrenort: (circleone) I 2 3 4 5 6 7(8) 9 l0 Date submitted: NGDO qartner: "l"""uivFzoog Sightsavers International South West 2 CDTI Project Report 2008 - Year 8. ANNUAL PROJECT TECHNICAL REPORT SUBMITTED TO TECHNICAL CONSULTATTVE COMMITTEE (TCC) DEADLINE FOR SUBMISSION: To APOC Management by 3l January for March TCC meeting To APOC Management by 31 Julv for September TCC meeting AFRICANPROGRAMME FOR ONCHOCERCTASTS CONTROL (APOC) I I RECU LE I S F[,;, ?ur], APOC iDIR ANNUAL I'II().I Ii(]'I"IIICHNICAL REPORT 't'o TECHNICAL CONSU l.',l'A]'tvE CoMMITTEE (TCC) ENDORSEMENT Please confirm you have read this report by signing in the appropriat space. OFFICERS to sign the rePort: Country: CAMEROON National Coordinator Name: Dr. Ntep Marcelline S l) u b Date: . ..?:.+/ c Ail 9ou R Regional Delegate Name: Dr. Chu + C( z z a tu Signature: n rJ ( Date 6t @ RY oF I DE LA NGDO Representative Name: Dr. Oye Joseph E Signature: .... Date:' g 2 JAN. u0g Regional Oncho Coordinator Name: Mr. Ebongo Signature: Date: 51-.12-Z This report has been prepared by Name : Mr. Ebongo Peter Designation:.OPC SWII Signature: *1.- ,l 1l Table of contents Acronyms .v Definitions vi FOLLOW UP ON TCC RECOMMENDATIONS. 7 Executive Summary.. 8 SECTION I : Background information......... 9 1.1. GrrueRruINFoRMATroN.................... 9 1.1.1 Description of the project...... 9 Location..... 9 1. 1. 2. -

Shelter Cluster Dashboard NWSW052021

Shelter Cluster NW/SW Cameroon Key Figures Individuals Partners Subdivisions Cameroon 03 23,143 assisted 05 Individual Reached Trend Nigeria Furu Awa Ako Misaje Fungom DONGA MANTUNG MENCHUM Nkambe Bum NORD-OUEST Menchum Nwa Valley Wum Ndu Fundong Noni 11% BOYO Nkum Bafut Njinikom Oku Kumbo Belo BUI Mbven of yearly Target Njikwa Akwaya Jakiri MEZAM Babessi Tubah Reached MOMO Mbeggwi Ngie Bamenda 2 Bamenda 3 Ndop Widikum Bamenda 1 Menka NGO KETUNJIA Bali Balikumbat MANYU Santa Batibo Wabane Eyumodjock Upper Bayang LEBIALEM Mamfé Alou OUEST Jan Feb Mar Apr May Jun Jul Aug Sep Oct Nov Dec Fontem Nguti KOUPÉ HNO/HRP 2021 (NW/SW Regions) Toko MANENGOUBA Bangem Mundemba SUD-OUEST NDIAN Konye Tombel 1,351,318 Isangele Dikome value Kumba 2 Ekondo Titi Kombo Kombo PEOPLE OF CONCERN Abedimo Etindi MEME Number of PoC Reached per Subdivision Idabato Kumba 1 Bamuso 1 - 100 Kumba 3 101 - 2,000 LITTORAL 2,001 - 13,000 785,091 Mbongé Muyuka PEOPLE IN NEED West Coast Buéa FAKO Tiko Limbé 2 Limbé 1 221,642 Limbé 3 [ Kilometers PEOPLE TARGETED 0 15 30 *Note : Sources: HNO 2021 PiN includes IDP, Returnees and Host Communi�es The boundaries and names shown and the designations used on this map do not imply official endorsement or acceptance by the United Nations Key Achievement Indicators PoC Reached - AGD Breakdouwn 296 # of Households assisted with Children 27% 26% emergency shelter 1,480 Adults 21% 22% # of households assisted with core 3,769 Elderly 2% 2% relief items including prevention of COVID-19 21,618 female male 41 # of households assisted with cash for rental subsidies 41 Households Reached Individuals Reached Cartegories of beneficiaries reported People Reached by region Distribution of Shelter NFI kits integrated with COVID 19 KITS in Matoh town. -

An Inventory of Short Horn Grasshoppers in the Menoua Division, West Region of Cameroon

AGRICULTURE AND BIOLOGY JOURNAL OF NORTH AMERICA ISSN Print: 2151-7517, ISSN Online: 2151-7525, doi:10.5251/abjna.2013.4.3.291.299 © 2013, ScienceHuβ, http://www.scihub.org/ABJNA An inventory of short horn grasshoppers in the Menoua Division, West Region of Cameroon Seino RA1, Dongmo TI1, Ghogomu RT2, Kekeunou S3, Chifon RN1, Manjeli Y4 1Laboratory of Applied Ecology (LABEA), Department of Animal Biology, Faculty of Science, University of Dschang, P.O. Box 353 Dschang, Cameroon, 2Department of Plant Protection, Faculty of Agriculture and Agronomic Sciences (FASA), University of Dschang, P.O. Box 222, Dschang, Cameroon. 3 Département de Biologie et Physiologie Animale, Faculté des Sciences, Université de Yaoundé 1, Cameroun 4 Department of Biotechnology and Animal Production, Faculty of Agriculture and Agronomic Sciences (FASA), University of Dschang, P.O. Box 222, Dschang, Cameroon. ABSTRACT The present study was carried out as a first documentation of short horn grasshoppers in the Menoua Division of Cameroon. A total of 1587 specimens were collected from six sites i.e. Dschang (265), Fokoue (253), Fongo – Tongo (267), Nkong – Ni (271), Penka Michel (268) and Santchou (263). Identification of these grasshoppers showed 28 species that included 22 Acrididae and 6 Pyrgomorphidae. The Acrididae belonged to 8 subfamilies (Acridinae, Catantopinae, Cyrtacanthacridinae, Eyprepocnemidinae, Oedipodinae, Oxyinae, Spathosterninae and Tropidopolinae) while the Pyrgomorphidae belonged to only one subfamily (Pyrgomorphinae). The Catantopinae (Acrididae) showed the highest number of species while Oxyinae, Spathosterninae and Tropidopolinae showed only one species each. Ten Acrididae species (Acanthacris ruficornis, Anacatantops sp, Catantops melanostictus, Coryphosima stenoptera, Cyrtacanthacris aeruginosa, Eyprepocnemis noxia, Gastrimargus africanus, Heteropternis sp, Ornithacris turbida, and Trilophidia conturbata ) and one Pyrgomorphidae (Zonocerus variegatus) were collected in all the six sites. -

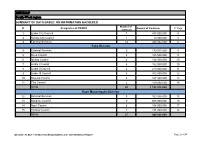

MINMAP South-West Region

MINMAP South-West region SUMMARY OF DATA BASED ON INFORMATION GATHERED Number of N° Designation of PO/DPO Amount of Contracts N° Page contracts 1 Limbe City Council 7 475 000 000 4 2 Kumba City Council 1 10 000 000 5 3 External Services 14 440 032 000 6 Fako Division 4 External Services 9 179 015 000 8 5 Buea Council 5 125 500 000 9 6 Idenau Council 4 124 000 000 10 7 Limbe I Council 4 152 000 000 10 8 Limbe II Council 4 219 000 000 11 9 Limbe III Council 6 102 500 000 12 10 Muyuka Council 6 127 000 000 13 11 Tiko Council 5 159 000 000 14 TOTAL 43 1 188 015 000 Kupe Muanenguba Division 12 External Services 5 100 036 000 15 13 Bangem Council 9 605 000 000 15 14 Nguti Council 6 104 000 000 17 15 Tombel Council 7 131 000 000 18 TOTAL 27 940 036 000 MINMAP / PUBLIC CONTRACTS PROGRAMMING AND MONITORING DIVISION Page 1 of 34 MINMAP South-West region SUMMARY OF DATA BASED ON INFORMATION GATHERED Lebialem Division 16 External Services 5 134 567 000 19 17 Alou Council 9 144 000 000 19 18 Menji Council 3 181 000 000 20 19 Wabane Council 9 168 611 000 21 TOTAL 26 628 178 000 Manyu Division 18 External Services 5 98 141 000 22 19 Akwaya Council 6 119 500 000 22 20 Eyomojock Council 6 119 000 000 23 21 Mamfe Council 5 232 000 000 24 22 Tinto Council 6 108 000 000 25 TOTAL 28 676 641 000 Meme Division 22 External Services 5 85 600 000 26 23 Mbonge Council 7 149 000 000 26 24 Konye Council 1 27 000 000 27 25 Kumba I Council 3 65 000 000 27 26 Kumba II Council 5 83 000 000 28 27 Kumba III Council 3 84 000 000 28 TOTAL 24 493 600 000 MINMAP / PUBLIC CONTRACTS -

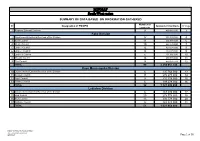

MINMAP South-West Region

MINMAP South-West region SUMMARY OF DATA BASED ON INFORMATION GATHERED Number of N° Designation of PO/DPO Amount of Contracts N° Page contracts 1 Regional External Services 9 490 982 000 3 Fako Division 2 Départemental External Services of the Division 17 352 391 000 4 3 Buea Council 11 204 778 000 6 4 Idenau Council 10 224 778 000 7 5 Limbe I Council 12 303 778 000 8 6 Limbe II Council 13 299 279 000 9 7 Limbe III Council 6 151 900 000 10 8 Muyuka Council 16 250 778 000 11 9 Tiko Council 14 450 375 748 12 TOTAL 99 2 238 057 748 Kupe Muanenguba Division 10 Départemental External Services of the Division 6 135 764 000 13 11 Bangem Council 11 572 278 000 14 12 Nguti Council 9 215 278 000 15 13 Tombel Council 6 198 278 000 16 TOTAL 32 1 121 598 000 Lebialem Division 14 Départemental External Services of the Division 6 167 474 000 17 15 Alou Council 20 278 778 000 18 16 Menji Council 13 306 778 000 20 17 Wabane Council 12 268 928 000 21 TOTAL 51 1 021 958 000 PUBLIC CONTRACTS PROGRAMMING AND MONITORING DIVISION /MINMAP Page 1 of 36 MINMAP South-West region SUMMARY OF DATA BASED ON INFORMATION GATHERED Number of N° Designation of PO/DPO Amount of Contracts N° Page contracts Manyu Division 18 Départemental External Services of the Division 9 240 324 000 22 19 Akwaya Council 10 260 278 000 23 20 Eyumojock Council 6 195 778 000 24 21 Mamfe Council 7 271 103 000 24 22 Tinto Council 7 219 778 000 25 TOTAL 39 1 187 261 000 Meme Division 23 Départemental External Services of the Division 4 82 000 000 26 24 Konye Council 5 171 533 000 26 25 Kumba -

South West Assessment

Cameroon Emergency Response – South West Assessment SOUTH WEST CAMEROON November 2018 – January 2019 - i - CONTENTS 1 CONTEXT ..................................................................................................................... 4 1.1 The crisis in numbers:.................................................................................................... 5 1.2 Overall Objectives of SW Assessment ........................................................................... 5 1.3 Area of Intervention ...................................................................................................... 6 2 METHODOLOGY .......................................................................................................... 6 2.1 Assessment site selection: ............................................................................................ 8 2.2 Configuration of the assessment team: ........................................................................ 8 2.3 Indicators of vulnerability verified during the rapid assessment: ................................ 9 2.3.1 Nutrition and Health ............................................................................................. 9 2.3.2 WASH ..................................................................................................................... 9 3.1.1 Food Security ......................................................................................................... 9 2.4 Sources of Information ............................................................................................... -

Assessing Cost Efficiency Among Small Scale Rice Producers in the West Region of Cameroon: a Stochastic Frontier Model Approach

International Journal of Humanities Social Sciences and Education (IJHSSE) Volume 3, Issue 6, June 2016, PP 1-7 ISSN 2349-0373 (Print) & ISSN 2349-0381 (Online) http://dx.doi.org/10.20431/2349-0381.0306001 www.arcjournals.org Assessing Cost Efficiency among Small Scale Rice Producers in the West Region of Cameroon: A Stochastic Frontier Model Approach Djomo, Raoul Fani*1, Ewung, Bethel1, Egbeadumah, Maryanne Odufa2 1Department of Agricultural Economics. University of Agriculture, Makurdi. Benue-State, Nigeria PMB 2373, Makurdi 2Department of Agricultural Economics and Extension, Federal University Wukari, PMB 1020 Wukari. Taraba State, Nigeria *[email protected] Abstract: Local farmers’ techniques and knowledge in rice cultivation being deficient and the aid system and research to support such farmers’ activities likewise insufficient, technological progress and increase in rice production are not yet assured. Therefore, this Study was undertaken to assess cost efficiency among small scale rice farmers in the West Region of Cameroon using stochastic frontier model approach. A purposive, multistage and stratified random sampling technique was used in selecting the respondents. A total of 192 small scale rice farmers were purposively selected from four (4) out of eight divisions. Data were collected using structured questionnaires and interview schedule, administered on the respondents were analyzed using descriptive statistics and stochastic frontier cost functions. The result indicates that the coefficient of cost of labour was found positive and significantly influence cost of production in small scale rice production at 1 percent level of probability, implying that increases in cost of labour by one unit will also increase cost of production in small scale rice farming by the value of it coefficient. -

2017/2018 Annual Report

Service to humanity TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF CONTENTS ..................................................................................................................................................... 1 ACRONYMS .................................................................................................................................................................... 2 ACKNOWLEDGMENT ..................................................................................................................................................... 4 FOREWORD .................................................................................................................................................................... 5 1. OVERVIEW OF AJESH ................................................................................................................................................. 6 1.1 Organisation Background .................................................................................................................................... 6 1.1.1 Vision ............................................................................................................................................................ 6 1.1.2 Mission ......................................................................................................................................................... 6 1.1.3 Global objective .......................................................................................................................................... -

A Collection of 100 Proverbs and Wise Sayings of the Medumba (Cameroon)

A COLLECTION OF 100 PROVERBS AND WISE SAYINGS OF THE MEDUMBA (CAMEROON) BY CIKURU BISHANGI DEVOTHA AFRICAN PROVERBS WORKING GROUP NAIROBI KENYA MAY 2019 i ACKNOWLEDGEMENT I wish to thank sincerely all those who contributed towards the completion of this document. My greatest thanks go to Fr. Joseph G. Healey for the financial and moral support. My special thanks go to Cephas Agbemenu, Margret Wambere Ireri and Father Joseph Healey. I also thank all the publishers of African Proverbs whose publications gave me good resource and inspiration to do this work. I appreciate the support of the African Proverbs Working Group for reviewing the progress of my work during their meetings. Find in this work all my gratitude. DEDICATION I dedicate this work to God for protecting and strengthening me while working on the Medumba. To HONDI M. Placide, my husband and my mentor who encouraged me to complete this research, To my collaborator Emmanuel Fandja who helped me to collect the 100 Medumba Proverbs. To all the members of my community in Nairobi and to all those who will appreciate in finding out the wisdom that it contains. i A COLLECTION OF 100 MEDUMBA PROVERBS AND WISE SAYINGS (CAMEROOON) INTRODUCTION Location The Bamileke is the native group which is now dominant in Cameroon's West and Northwest Regions. It is part of the Semi-Bantu (or Grassfields Bantu) ethnic group. The Bamileke are regrouped under several groups, each under the guidance of a chief or fon. Nonetheless, all of these groups have the same ancestors and thus share the same history, culture, and languages. -

Joshua Osih President

Joshua Osih President THE STRENGTH OF OUR DIVERSITY PRESIDENTIAL ELECTION 2018 JOSHUA OSIH | THE STRENGTH OF OUR DIVERSITY | P . 1 MY CONTRACT WITH THE NATION Build a new Cameroon through determination, duty to act and innovation! I decided to run in the presidential election of October 7th to give the youth, who constitute the vast majority of our population, the opportunity to escape the despair that has gripped them for more than three decades now, to finally assume responsibility for the future direction of our highly endowed nation. The time has come for our youth to rise in their numbers in unison and take control of their destiny and stop the I have decided to run in the presidential nation’s descent into the abyss. They election on October 7th. This decision, must and can put Cameroon back on taken after a great deal of thought, the tracks of progress. Thirty-six years arose from several challenges we of selfish rule by an irresponsible have all faced. These crystalized into and corrupt regime have brought an a single resolution: We must redeem otherwise prosperous Cameroonian Cameroon from the abyss of thirty-six nation to its knees. The very basic years of low performance, curb the elements of statecraft have all but negative instinct of conserving power disappeared and the citizenry is at all cost and save the collapsing caught in a maelstrom. As a nation, system from further degradation. I we can no longer afford adequate have therefore been moved to run medical treatment, nor can we provide for in the presidential election of quality education for our children.