Diversity: a Philosophical Perspective

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Amos Yong Complete Curriculum Vitae

Y o n g C V | 1 AMOS YONG COMPLETE CURRICULUM VITAE Table of Contents PERSONAL & PROFESSIONAL DATA ..................................................................................... 2 Education ................................................................................................................................................... 2 Academic & Administrative Positions & Other Employment .................................................................... 3 Visiting Professorships & Fellowships ....................................................................................................... 3 Memberships & Certifications ................................................................................................................... 3 PUBLICATIONS ............................................................................................................................ 4 Monographs/Books – and Reviews Thereof.............................................................................................. 4 Edited Volumes – and Reviews Thereof .................................................................................................. 11 Co-edited Book Series .............................................................................................................................. 16 Missiological Engagements: Church, Theology and Culture in Global Contexts (IVP Academic) – with Scott W. Sunquist and John R. Franke ................................................................................................ -

<[email protected]> 15 January 2021 Department of Philosophy

Sahotra Sarkar University of Texas at Austin E-mail: <[email protected]> 15 January 2021 Department of Philosophy, Department of Integrative Biology, 2210 Speedway, C3500, 205 West 24th St., C0930, Austin, TX 78712 -1180. Austin, TX 78712 -0253. Office: (512) 232 -7122. Office: (512) 232 -3800. FAX: (512) 471 -4806. FAX: (512) 471 -3878. Research Areas: Philosophy and History of Science; Biomedical Humanities; Environmental Philosophy; Formal Epistemology; History of Philosophy of Science; Conservation Biology; Disease Ecology and Epidemiology. Education 1981 -89: University of Chicago: M.A. 1984 (Conceptual Foundations of Science); Ph.D. 1989 (Philosophy). 1977 -81: Columbia University: B.A. 1981 (Mathematics, Philosophy, Physics). Professional Experience Fall 2003 –present: Professor, Department of Philosophy, Department of Integrative Biology, and Center for Computational Biology and Bioinformatics, University of Texas at Austin. Spring 2017 –Spring 2019: Distinguished University Fellow, Presidency University, Kolkata. Fall 2006 –Spring 2007: Graduate Faculty, Institute of Biology, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, Mexico City. Fall 2002 –Spring 2003: Visiting Scholar, Max-Planck-Institut für Wissenschaftsgeschichte in Berlin. 1 Fall 2001 –Spring 2010: Co-Director, Environmental Sciences Center, Hornsby Bend, Austin. Fall 1998 –Spring 2002: Associate Professor, Department of Philosophy, and Director, Program in the History and Philosophy of Science, University of Texas at Austin. Fall 1997 –Spring 2000: Research Associate, Redpath Museum, McGill University. Fall 1997 –Spring 1998: Visiting Professor, Departments of Biology and Philosophy, McGill University. Fall 1997 –Spring 1998: Visiting Scholar, Max-Planck-Institut für Wissenschaftsgeschichte in Berlin. Fall 1996 –Spring 1997: Fellow, Wissenschaftskolleg zu Berlin. Fall 1994 –Spring 1996: Visiting Associate Professor, Department of Philosophy, McGill University. -

Doctoraat FINAAL .Pdf

Here be dragons Here Exploring the hinterland of science Maarten Boudry Here be dragons Exploring the hinterland of science Maarten Boudry ISBN978-90-7083-018-2 Proefschrift voorgedragen tot het bekomen van de graad van Doctor in de Wijsbegeerte Promotor: Prof. dr. Johan Braeckman Supervisor Prof. dr. Johan Braeckman Wijsbegeerte en moraalwetenschap Dean Prof. dr. Freddy Mortier Rector Prof. dr. Paul Van Cauwenberghe Nederlandse vertaling: Hic sunt dracones. Een filosofische verkenning van pseudowetenschap en randwetenschap Cover: The image on the front cover is an excerpt of a map by the Flemish cartographer Abraham Ortelius, originally published in Theatrum Orbis Terrarum (1570). ISBN: 978-90-7083-018-2 The author and the promoter give the authorisation to consult and to copy parts of this work for personal use only. Every other use is subject to the copyright laws. Permission to reproduce any material contained in this work should be obtained from the author. Faculty of Arts & Humanities Maarten Boudry Here be Dragons Exploring the Hinterland of Science Proefschrift voorgedragen tot het bekomen van de graad van Doctor in de Wijsbegeerte 2011 Acknowledgements This dissertation could not have been written without the invaluable help of a number of people (a philosopher cannot help but thinking of them as a set of individually necessary and jointly sufficient conditions). Different parts of this work have greatly benefited from stimulating discussions with many colleagues and friends, among whom Barbara Forrest, John Teehan, Herman Philipse, Helen De Cruz, Taner Edis, Nicholas Humphrey, Geerdt Magiels, Bart Klink, Glenn Branch, Larry Moran, Jerry Coyne, Michael Ruse, Steve Zara, Amber Griffioen, Johan De Smedt, Lien Van Speybroeck, and Evan Fales. -

Sahotra Sarkar University of Texas at Austin E-Mail

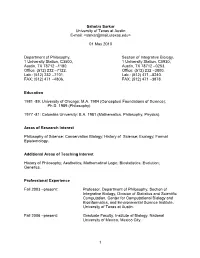

Sahotra Sarkar University of Texas at Austin E-mail: <[email protected]> 01 August 2012 Department of Philosophy, Section of Integrative Biology, 1 University Station, C3500, 1 University Station, C0930, Austin, TX 78712 –1180. Austin, TX 78712 –0253. Office: (512) 232 –7122. Office: (512) 232 –3800. Lab.: (512) 232 –7101. Lab.: (512) 471 –8240. FAX: (512) 471 –4806. FAX: (512) 471 –3878. Education 1981 -89: University of Chicago: M.A. 1984 (Conceptual Foundations of Science); Ph.D. 1989 (Philosophy). 1977 -81: Columbia University: B.A. 1981 (Mathematics, Philosophy, Physics). Areas of Research Interest Philosophy of Science; Conservation Biology; History of Science; Formal Epistemology; History of Philosophy of Science; Disease Ecology and Epidemiology. Additional Areas of Teaching Interest History of Philosophy; Aesthetics; Mathematical Logic; Evolution; Genetics. Professional Experience Fall 2003 –present: Professor, Department of Philosophy, Section of Integrative Biology, Division of Statistics and Scientific Computation, Center for Computational Biology and Bioinformatics, and Environmental Science Institute, University of Texas at Austin. Fall 2006 –present: Graduate Faculty, Institute of Biology, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, Mexico City. Fall 2001 –Spring 2010: Co-Director, Environmental Sciences Center, Hornsby Bend, Austin. 1 Fall 1998 –Spring 2002: Associate Professor, Department of Philosophy; and Director, Program in the History and Philosophy of Science, University of Texas at Austin. Fall 1997 – Spring 2000: Research Associate, Redpath Museum, McGill University. Fall 1997 –Spring 1998: Visiting Scholar, Max-Planck-Institut für Wissenschaftsgeschichte in Berlin. Visiting Professor, Departments of Biology and Philosophy, McGill University. Fall 1996 –Spring 1997: Fellow, Wissenschaftskolleg zu Berlin. Fall 1994 –Spring 1996: Visiting Associate Professor, Department of Philosophy, McGill University. -

<[email protected]> 01 January 2011 Department of Philosophy, 1

Sahotra Sarkar University of Texas at Austin E-mail: <[email protected]> 01 January 2011 Department of Philosophy, Section of Integrative Biology, 1 University Station, C3500, 1 University Station, C0930, Austin, TX 78712 –1180. Austin, TX 78712 –0253. Office: (512) 232 –7122. Office: (512) 232 –3800. Lab.: (512) 232 –7101. Lab.: (512) 471 –8240. FAX: (512) 471 –4806. FAX: (512) 471 –3878. Education 1981 -89: University of Chicago: M.A. 1984 (Conceptual Foundations of Science); Ph.D. 1989 (Philosophy). 1977 -81: Columbia University: B.A. 1981 (Mathematics, Philosophy, Physics). Areas of Research Interest Philosophy of Science; History of Science; Formal Epistemology; Conservation Biology. Additional Areas of Teaching Interest History of Philosophy; Aesthetics; Mathematical Logic; Biostatistics; Evolution; Genetics. Professional Experience Fall 2003 –present: Professor, Department of Philosophy, Section of Integrative Biology, Division of Statistics and Scientific Computation, Center for Computational Biology and Bioinformatics, and Environmental Science Institute, University of Texas at Austin. Fall 2006 –present: Graduate Faculty, Institute of Biology, National University of Mexico, Mexico City. 1 Fall 2001 –present: Co-Director, Environmental Sciences Center, Hornsby Bend, Austin. Fall 1998 –Spring 2002: Associate Professor, Department of Philosophy; and Director, Program in the History and Philosophy of Science, University of Texas at Austin. Fall 1997 – Spring 2000: Research Associate, Redpath Museum, McGill University. Fall 1997 –Spring 1998: Visiting Scholar, Max-Planck-Institut für Wissenschaftsgeschichte in Berlin. Visiting Professor, Departments of Biology and Philosophy, McGill University. Fall 1996 –Spring 1997: Fellow, Wissenschaftskolleg zu Berlin. Fall 1994 –Spring 1996: Visiting Associate Professor, Department of Philosophy, McGill University. Fall 1993 –Spring 1994: Fellow, Dibner Institute for the History of Science and Technology, MIT. -

Signature in the Cell

Signature in the Cell DNA and the Evidence for Intelligent Design Stephen C. Meyer FOR ELAINE, ONCE AND FUTURE COMPANION Contents Prologue Chapter 1 DNA, Darwin, and the Appearance of Design Chapter 2 The Evolution of a Mystery and Why It Matters Chapter 3 The Double Helix Chapter 4 Signature in the Cell Chapter 5 The Molecular Labyrinth Chapter 6 The Origin of Science and the Possibility of Design Chapter 7 Of Clues to Causes Chapter 8 Chance Elimination and Pattern Recognition Chapter 9 Ends and Odds Chapter 10 Beyond the Reach of Chance Chapter 11 Self-Organization and Biochemical Predestination Chapter 12 Thinking Outside the Bonds Chapter 13 Chance and Necessity, or the Cat in the Hat Comes Back Chapter 14 The RNA World Chapter 15 The Best Explanation Chapter 16 Another Road to Rome Chapter 17 But Does It Explain? Chapter 18 But Is It Science? Chapter 19 Sauce for the Goose Chapter 20 Why It Matters Epilogue: A Living Science Appendix A: Some Predictions of Intelligent Design Appendix B: Multiverse Cosmology and the Origin of Life Notes Bibliography Searchable Terms Acknowledgments About the Author Praise Credits Copyright About the Publisher Prologue “Dad, that’s you!” my fourteen-year-old son exclaimed as he looked at the newspaper while we stood waiting to check out at the tiny general store. His shock at seeing my face in the front section of the Seattle Post-Intelligencer, when he just went to look for baseball scores, was no doubt compounded by his awareness of our location.1 The general store on Shaw Island, one of the most remote in the San Juan chain north of Puget Sound, was the only commercial establishment on the island. -

Sahotra Sarkar · Ben A. Minteer Editors a Sustainable Philosophy— the Work of Bryan Norton the International Library of Environmental, Agricultural and Food Ethics

The International Library of Environmental, Agricultural and Food Ethics 26 Sahotra Sarkar · Ben A. Minteer Editors A Sustainable Philosophy— The Work of Bryan Norton The International Library of Environmental, Agricultural and Food Ethics Volume 26 Series editors Michiel Korthals, Wageningen, The Netherlands Paul B. Thompson, Michigan, USA The ethics of food and agriculture is confronted with enormous challenges. Scientific developments in the food sciences promise to be dramatic; the concept of life sciences, that comprises the integral connection between the biological sciences, the medical sciences and the agricultural sciences, got a broad start with the genetic revolution. In the mean time, society, i.e., consumers, producers, farmers, policymakers, etc, raised lots of intriguing questions about the implications and presuppositions of this revolution, taking into account not only scientific developments, but societal as well. If so many things with respect to food and our food diet will change, will our food still be safe? Will it be produced under animal friendly conditions of husbandry and what will our definition of animal welfare be under these conditions? Will food production be sustainable and environmentally healthy? Will production consider the interest of the worst off and the small farmers? How will globalisation and liberalization of markets influence local and regional food production and consumption patterns? How will all these develop- ments influence the rural areas and what values and policies are ethically sound? All these questions raise fundamental and broad ethical issues and require enormous ethical theorizing to be approached fruitfully. Ethical reflection on criteria of animal welfare, sustainability, liveability of the rural areas, biotechnol- ogy, policies and all the interconnections is inevitable. -

Sahotra Sarkar University of Texas at Austin E-Mail: <[email protected]> 01 May 2010 Department of Philosophy, 1 Univ

Sahotra Sarkar University of Texas at Austin E-mail: <[email protected]> 01 May 2010 Department of Philosophy, Section of Integrative Biology, 1 University Station, C3500, 1 University Station, C0930, Austin, TX 78712 –1180. Austin, TX 78712 –0253. Office: (512) 232 –7122. Office: (512) 232 –3800. Lab.: (512) 232 –7101. Lab.: (512) 471 –8240. FAX: (512) 471 –4806. FAX: (512) 471 –3878. Education 1981 -89: University of Chicago: M.A. 1984 (Conceptual Foundations of Science); Ph.D. 1989 (Philosophy). 1977 -81: Columbia University: B.A. 1981 (Mathematics, Philosophy, Physics). Areas of Research Interest Philosophy of Science; Conservation Biology; History of Science; Ecology; Formal Epistemology. Additional Areas of Teaching Interest History of Philosophy; Aesthetics; Mathematical Logic; Biostatistics; Evolution; Genetics. Professional Experience Fall 2003 –present: Professor, Department of Philosophy, Section of Integrative Biology, Division of Statistics and Scientific Computation, Center for Computational Biology and Bioinformatics, and Environmental Science Institute, University of Texas at Austin. Fall 2006 –present: Graduate Faculty, Institute of Biology, National University of Mexico, Mexico City. 1 Fall 2001 –present: Co-Director, Environmental Sciences Center, Hornsby Bend, Austin. Fall 1998 –Spring 2002: Associate Professor, Department of Philosophy; and Director, Program in the History and Philosophy of Science, University of Texas at Austin. Fall 1997 – Spring 2000: Research Associate, Redpath Museum, McGill University. Fall 1997 –Spring 1998: Visiting Scholar, Max-Planck-Institut für Wissenschaftsgeschichte in Berlin. Visiting Professor, Departments of Biology and Philosophy, McGill University. Fall 1996 –Spring 1997: Fellow, Wissenschaftskolleg zu Berlin. Fall 1994 –Spring 1996: Visiting Associate Professor, Department of Philosophy, McGill University. Fall 1993 –Spring 1994: Fellow, Dibner Institute for the History of Science and Technology, MIT. -

An Optimization Model for Disease Intervention

An Optimization Model for Disease Intervention Speaker: Professor Sahotra Sarkar Venue: Room 305, Samuels building, UNSW upper campus, Randwick Date: Thursday 3 April 2014 Time: 12-1pm Enquiries: [email protected] Parking: Level 5 of the parking station; enter via Gate 11 Botany St, Randwick Map: http://www.facilities.unsw.edu.au/sites/all/files/page_file_attachment/KENC%20Campus.pdf SPEAKER BIOGRAPHY Dr. Sahotra Sarkar is a Professor at the University of Texas at Austin. He earned a BA from Columbia University, and a MA and PhD from the University of Chicago. He was a Fellow of the Wissenschaftskolleg zu Berlin (1996 -1997), the Dibner Institute for the History of Science (1993 -1994), and the Edelstein Centre for the Philosophy of Science (1992). He was a Visiting Scholar at the Max Planck Institute for the History of Science in Berlin (1997 - 1998, 2002 -2003) and taught at McGill University before moving to Texas. He is a specialist in the history and philosophy of science with particular interests in both philosophy of biology and physics. He is the author of Genetics and Reductionism: A Primer ; (Cambridge, 1998) and J.B.S. Haldane--A Scientific Biography (Oxford, forthcoming); editor of several books, including The Philosophy and History of Molecular Biology (1996), the six- volume Science and the Philosophy in the Twentieth Century: Basic Works of Logical Empiricism (1996) and the two-volume The Philosophy of Science: An Encyclopedia (forthcoming); and author of several dozen articles in both philosophical and scientific journals. His teaching and research also encompass mathematical logic, environmental ethics, aesthetics, and Marx. -

Sahotra Sarkar University of Texas at Austin E-Mail: <[email protected]> 15 February 2019 Department of Philosophy

Sahotra Sarkar University of Texas at Austin E-mail: <[email protected]> 15 February 2019 Department of Philosophy, Department of Integrative Biology, 2210 Speedway, C3500, 205 West 24th St., C0930, Austin, TX 78712 -1180. Austin, TX 78712 -0253. Office: (512) 232 -7122. Office: (512) 232 -3800. FAX: (512) 471 -4806. FAX: (512) 471 -3878. Research Areas: Philosophy and History of Science; Biomedical Humanities; Environmental Philosophy; Formal Epistemology; History of Philosophy of Science; Conservation Biology; Disease Ecology and Epidemiology. Education 1981 -89: University of Chicago: M.A. 1984 (Conceptual Foundations of Science); Ph.D. 1989 (Philosophy). 1977 -81: Columbia University: B.A. 1981 (Mathematics, Philosophy, Physics). Professional Experience Fall 2003 –present: Professor, Department of Philosophy, Department of Integrative Biology, and Center for Computational Biology and Bioinformatics, University of Texas at Austin. Spring 2017 –present Distinguished University Fellow, Presidency University, Kolkata. Fall 2006 –Spring 2007: Graduate Faculty, Institute of Biology, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, Mexico City. Fall 2002 –Spring 2003: Visiting Scholar, Max-Planck-Institut für Wissenschaftsgeschichte in Berlin. 1 Fall 2001 –Spring 2010: Co-Director, Environmental Sciences Center, Hornsby Bend, Austin. Fall 1998 –Spring 2002: Associate Professor, Department of Philosophy, and Director, Program in the History and Philosophy of Science, University of Texas at Austin. Fall 1997 –Spring 2000: Research Associate, Redpath Museum, McGill University. Fall 1997 –Spring 1998: Visiting Professor, Departments of Biology and Philosophy, McGill University. Fall 1997 –Spring 1998: Visiting Scholar, Max-Planck-Institut für Wissenschaftsgeschichte in Berlin. Fall 1996 –Spring 1997: Fellow, Wissenschaftskolleg zu Berlin. Fall 1994 –Spring 1996: Visiting Associate Professor, Department of Philosophy, McGill University.