Population Genetic Structure of Two Rare Tree Species (Colubrina

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pu'u Wa'awa'a Biological Assessment

PU‘U WA‘AWA‘A BIOLOGICAL ASSESSMENT PU‘U WA‘AWA‘A, NORTH KONA, HAWAII Prepared by: Jon G. Giffin Forestry & Wildlife Manager August 2003 STATE OF HAWAII DEPARTMENT OF LAND AND NATURAL RESOURCES DIVISION OF FORESTRY AND WILDLIFE TABLE OF CONTENTS TITLE PAGE ................................................................................................................................. i TABLE OF CONTENTS ............................................................................................................. ii GENERAL SETTING...................................................................................................................1 Introduction..........................................................................................................................1 Land Use Practices...............................................................................................................1 Geology..................................................................................................................................3 Lava Flows............................................................................................................................5 Lava Tubes ...........................................................................................................................5 Cinder Cones ........................................................................................................................7 Soils .......................................................................................................................................9 -

List 01 Hawaiian Names 01 Plants

V\.{). 3 v BOTANICAL BULLETIN NO.2 JUNE. 1913 TERRITORY OF HAWAII BOARD OF AGRICULTURE AND FORESTRY List 01 Hawaiian Names 01 Plants BY JOSEPH F. ROCK Consulting Botanist, Board of Agriculture and Forestry HONOLULU: HAWAIIAN GAZETTE CO., LTD. 1913 ALPHABETICAL LIST OF HAWAIIAN NAMES OF PLANTS. The following list of Hawaiian plant-names has been compiled from various sources. Hillebrand in his valuable Flora of the Hawaiian Islands has given many Hawaiian names, especially of the more common species; these are incorporated in this list with a few corrections. Nearly all Hawaiian plant-names found in this list and not in Hillebrand's Flora were secured from Mr. Francis Gay of the Island of Kauai, an old resident in this Terri tory and well acquainted with its plants from a layman's stand point. It was the writer's privilege to camp with Mr. Gay in the mountains of Kauai collecting botanical material; for almost every species he could give the native name, which he had se cured in the early days from old and reliable natives. Mr. Gay had made spatter prints of many of the native plants in a large record book with their names and uses, as well as their symbolic meaning when occurring in mele (songs) or olioli (chants), at tached to them. For all this information the writer is indebted mainly to Mr. Francis Gay and also to Mr. Augustus F. Knudsen of the same Island. The writer also secured Hawaiian names from old na tives and Kahunas (priests) in the various islands of the group. -

Kingdom Class Family Scientific Name Common Name I Q a Records

Kingdom Class Family Scientific Name Common Name I Q A Records plants monocots Poaceae Paspalidium rarum C 2/2 plants monocots Poaceae Aristida latifolia feathertop wiregrass C 3/3 plants monocots Poaceae Aristida lazaridis C 1/1 plants monocots Poaceae Astrebla pectinata barley mitchell grass C 1/1 plants monocots Poaceae Cenchrus setigerus Y 1/1 plants monocots Poaceae Echinochloa colona awnless barnyard grass Y 2/2 plants monocots Poaceae Aristida polyclados C 1/1 plants monocots Poaceae Cymbopogon ambiguus lemon grass C 1/1 plants monocots Poaceae Digitaria ctenantha C 1/1 plants monocots Poaceae Enteropogon ramosus C 1/1 plants monocots Poaceae Enneapogon avenaceus C 1/1 plants monocots Poaceae Eragrostis tenellula delicate lovegrass C 2/2 plants monocots Poaceae Urochloa praetervisa C 1/1 plants monocots Poaceae Heteropogon contortus black speargrass C 1/1 plants monocots Poaceae Iseilema membranaceum small flinders grass C 1/1 plants monocots Poaceae Bothriochloa ewartiana desert bluegrass C 2/2 plants monocots Poaceae Brachyachne convergens common native couch C 2/2 plants monocots Poaceae Enneapogon lindleyanus C 3/3 plants monocots Poaceae Enneapogon polyphyllus leafy nineawn C 1/1 plants monocots Poaceae Sporobolus actinocladus katoora grass C 1/1 plants monocots Poaceae Cenchrus pennisetiformis Y 1/1 plants monocots Poaceae Sporobolus australasicus C 1/1 plants monocots Poaceae Eriachne pulchella subsp. dominii C 1/1 plants monocots Poaceae Dichanthium sericeum subsp. humilius C 1/1 plants monocots Poaceae Digitaria divaricatissima var. divaricatissima C 1/1 plants monocots Poaceae Eriachne mucronata forma (Alpha C.E.Hubbard 7882) C 1/1 plants monocots Poaceae Sehima nervosum C 1/1 plants monocots Poaceae Eulalia aurea silky browntop C 2/2 plants monocots Poaceae Chloris virgata feathertop rhodes grass Y 1/1 CODES I - Y indicates that the taxon is introduced to Queensland and has naturalised. -

Honey and Pollen Flora of SE Australia Species

List of families - genus/species Page Acanthaceae ........................................................................................................................................................................34 Avicennia marina grey mangrove 34 Aizoaceae ............................................................................................................................................................................... 35 Mesembryanthemum crystallinum ice plant 35 Alliaceae ................................................................................................................................................................................... 36 Allium cepa onions 36 Amaranthaceae ..................................................................................................................................................................37 Ptilotus species foxtails 37 Anacardiaceae ................................................................................................................................................................... 38 Schinus molle var areira pepper tree 38 Schinus terebinthifolius Brazilian pepper tree 39 Apiaceae .................................................................................................................................................................................. 40 Daucus carota carrot 40 Foeniculum vulgare fennel 41 Araliaceae ................................................................................................................................................................................42 -

Sato Hawii 0085O 10652.Pdf

RESTORATION OF HAWAIIAN TROPICAL DRY FORESTS: A BIOCULTURAL APPROACH A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE DIVISION OF THE UNIVERSITY OF HAWAI‘I AT MĀNOA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF SCIENCE IN BOTANY (CONSERVATION BIOLOGY) MAY 2020 By Aimee Y. Sato Thesis Committee: Tamara Ticktin, Chairperson Christian P. Giardina Rakan A. Zahawi Kewords: Tropical Dry Forest, Biocultural, Conservation, Restoration, Natural Regeneration, Social-Ecological 1 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I thank my graduate committee for steering and guiding me through my thesis work. Dr. Tamara Ticktin, my thesis advisor who has been the greatest kumu (teacher) that I could have asked for in my research. I also thank my two committee members, Dr. Rakan A. Zahawi and Dr. Christian P. Giardina, who both brought their expansive levels of expertise to help develop this thesis. Thank you so much to the hoaʻāina (caretakers/restoration managers) of my two project sites. I thank the hoaʻāina of Kaʻūpūlehu, ‘Aunty’ Yvonne Carter, ‘Uncle’ Keoki Carter, Wilds Brawner, Kekaulike Tomich, Lehua Alapai, Kuʻulei Keakealani, and ‘Aunty’ Hannah Kihalani Springer. Thank you to the hoaʻāina of Auwahi, Art Medeiros, Erica von-Allmen, Ainoa and Kalaʻau Kaiaokamalie, Amy Campbell, Andy Bieber, Robert Pitts, and Kailie Aina. I would also like to acknowledge Kamehameha Schools and the Ulupalakua Ranch for allowing me to conduct this research on their lands. Thank you to the dry forest restoration managers and researchers that participated in the overview survey of Hawaiian dry forests. On Oʻahu Island: Lorena ‘Tap’ Wada, James Harmon and Kapua Kawelo. On Hawaiʻi Island: Elliott Parsons, Rebecca Most, Lena Schnell, Kalā Asing, Jen Lawson, and Susan Cordell. -

Brisbane Native Plants by Suburb

INDEX - BRISBANE SUBURBS SPECIES LIST Acacia Ridge. ...........15 Chelmer ...................14 Hamilton. .................10 Mayne. .................25 Pullenvale............... 22 Toowong ....................46 Albion .......................25 Chermside West .11 Hawthorne................. 7 McDowall. ..............6 Torwood .....................47 Alderley ....................45 Clayfield ..................14 Heathwood.... 34. Meeandah.............. 2 Queensport ............32 Trinder Park ...............32 Algester.................... 15 Coopers Plains........32 Hemmant. .................32 Merthyr .................7 Annerley ...................32 Coorparoo ................3 Hendra. .................10 Middle Park .........19 Rainworth. ..............47 Underwood. ................41 Anstead ....................17 Corinda. ..................14 Herston ....................5 Milton ...................46 Ransome. ................32 Upper Brookfield .......23 Archerfield ...............32 Highgate Hill. ........43 Mitchelton ...........45 Red Hill.................... 43 Upper Mt gravatt. .......15 Ascot. .......................36 Darra .......................33 Hill End ..................45 Moggill. .................20 Richlands ................34 Ashgrove. ................26 Deagon ....................2 Holland Park........... 3 Moorooka. ............32 River Hills................ 19 Virginia ........................31 Aspley ......................31 Doboy ......................2 Morningside. .........3 Robertson ................42 Auchenflower -

Alphitonia Excelsa Common Name: Red Ash Family - Rhamnaceae

Alphitonia Excelsa Common Name: Red Ash Family - Rhamnaceae Description • Alphitonia Excelsa is a small to medium size tree with a branching canopy formation • Reaches a height of 15m and width of 6m • The tree is commonly found in dry sclerophyll forest and rainforests • Favours well drained soils and is highly suitable for erosion control areas • Fast growing ability, highly suitable for areas prone to coastal salty winds and drought condition • Prefers full sun conditions • Spectacular cream ‘petal-like’ flowers appear from summer to autumn • Ecological role provides a habitat for native birds (cockatoos) and the small green-banded blue butterfly • Round black fruit ripens from June to September • Distribution occurs from the coastal areas of WA across the top end of the NT, and along the coastline from Northern Qld to the southern coastal areas of NSW How to look after this plant • Prefers full sun • When planting tree into ground, dig a slow release native fertiliser (low phosphorous formulation) into soil to provide plant with essential nutrients, encourage healthy plant growth and increase flowering. Slow release fertiliser will generally last up to 6 months, reapply between 5-6 months to continue plant growth • Water every 2-3 days a week for the first month when planted. Cut back watering to once or twice a week after the first month (avoid over watering) • Lightly prune after the flowering season to increase the foliage growth • If soil is low in organic matter, dig compost into existing soil to develop valuable humus around your plant. • For clay soils, dig gypsum and garden soil into the existing ground to encourage drainage. -

Reproductive Ecology and Population Genetics of Hawaiian Wiliwili, Erythrina Sandwicensis (Fabaceae)

REPRODUCTIVE ECOLOGY AND POPULATION GENETICS OF HAWAIIAN WILIWILI, ERYTHRINA SANDWICENSIS (FABACEAE) A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE DIVISION OF THE UNIVERSITY OF HAWAI‘I AT MĀNOA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF SCIENCE IN BOTANY (ECOLOGY, EVOLUTION, AND CONSERVATION BIOLOGY) AUGUST 2018 By Emily F. Grave Thesis Committee: Tamara Ticktin (Chairperson) Curt Daehler Cliff Morden Daniela Elliot Keywords: dry forest, pollination biology, population genetics, conservation biology, Erythrina DEDICATION I would like to dedicate this work, and resulting thesis, to my late mother Barbara Jean Grave. My true love of nature was fostered through my first teacher, my mom, who never stopped learning and teaching me about the beauty, wonder, and significance of the world around us. And to my son, Sebastian, for whom I hope to bestow upon my fascination with our enigmatic ecosystems. ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to take this opportunity to thank the many people who have sacrificed their time to advance this project and its several components. My committee members, Tamara Ticktin, Curt Daehler, Daniela Elliot, and Cliff Morden have been incredibly insightful and supportive, and have helped propel this study into fruition. My field assistant and partner, Tim Kroessig, was instrumental in formulating the basis behind this research. From realizing the importance of the research, to the proposal and permitting, to hours of field work, and onward through the data collection phase, Tim helped make this study a successful reality. His ideas and innovations greatly strengthened the results of the research. I am very grateful to my lab mates: Reko Libby, Zoe Hastings, Georgia Fredeluces-Hart, Ashley McGuigan, Gioconda López, and Leo Beltran (and Solomon Champion and Miles Thomas as well), who spent several hours in (and out of) the field with me. -

*Wagner Et Al. --Intro

NUMBER 60, 58 pages 15 September 1999 BISHOP MUSEUM OCCASIONAL PAPERS HAWAIIAN VASCULAR PLANTS AT RISK: 1999 WARREN L. WAGNER, MARIE M. BRUEGMANN, DERRAL M. HERBST, AND JOEL Q.C. LAU BISHOP MUSEUM PRESS HONOLULU Printed on recycled paper Cover illustration: Lobelia gloria-montis Rock, an endemic lobeliad from Maui. [From Wagner et al., 1990, Manual of flowering plants of Hawai‘i, pl. 57.] A SPECIAL PUBLICATION OF THE RECORDS OF THE HAWAII BIOLOGICAL SURVEY FOR 1998 Research publications of Bishop Museum are issued irregularly in the RESEARCH following active series: • Bishop Museum Occasional Papers. A series of short papers PUBLICATIONS OF describing original research in the natural and cultural sciences. Publications containing larger, monographic works are issued in BISHOP MUSEUM four areas: • Bishop Museum Bulletins in Anthropology • Bishop Museum Bulletins in Botany • Bishop Museum Bulletins in Entomology • Bishop Museum Bulletins in Zoology Numbering by volume of Occasional Papers ceased with volume 31. Each Occasional Paper now has its own individual number starting with Number 32. Each paper is separately paginated. The Museum also publishes Bishop Museum Technical Reports, a series containing information relative to scholarly research and collections activities. Issue is authorized by the Museum’s Scientific Publications Committee, but manuscripts do not necessarily receive peer review and are not intended as formal publications. Institutions and individuals may subscribe to any of the above or pur- chase separate publications from Bishop Museum Press, 1525 Bernice Street, Honolulu, Hawai‘i 96817-0916, USA. Phone: (808) 848-4135; fax: (808) 841-8968; email: [email protected]. Institutional libraries interested in exchanging publications should write to: Library Exchange Program, Bishop Museum Library, 1525 Bernice Street, Honolulu, Hawai‘i 96817-0916, USA; fax: (808) 848-4133; email: [email protected]. -

Auwahi: Ethnobotany of a Hawaiian Dryland Forest

AUWAHI: ETHNOBOTANY OF A HAWAIIAN DRYLAND FOREST. A. C. Medeiros1, C.F. Davenport2, and C.G. Chimera1 1. U.S. Geological Survey, Biological Resources Division, Haleakala Field Station, P.O. Box 369, Makawao, HI 96768 2. Social Sciences Department, Maui Community College, 310 Ka’ahumanu Ave., Kahului, HI 96732 ABSTRACT Auwahi district on East Maui extends from sea level to about 6800 feet (1790 meters) elevation at the southwest rift of leeward Haleakal¯a volcano. In botanical references, Auwahi currently refers to a centrally located, fairly large (5400 acres) stand of diverse dry forest at 3000-5000 feet (915- 1525 meters) elevation surrounded by less diverse forest and more open-statured shrubland on lava. Auwahi contains high native tree diversity with 50 dryland species, many with extremely hard, durable, and heavy wood. To early Hawaiians, forests like Auwahi must have seemed an invaluable source of unique natural materials, especially the wide variety of woods for tool making for agriculture and fishing, canoe building, kapa making, and weapons. Of the 50 species of native trees at Auwahi, 19 species (38%) are known to have been used for medicine, 13 species (26%) for tool-making, 13 species (26%) for canoe building 13 species (26%) for house building, 8 species (16%) for tools for making kapa, 8 species (16%) for weapons 8 species (16%) for fishing, 8 species (16%) for dyes, and 7 species (14 %) for religious purposes. Other miscellaneous uses include edible fruits or seeds, bird lime, cordage, a fish narcotizing agent, firewood, a source of "fireworks", recreation, scenting agents, poi boards, and h¯olua sled construction. -

Alphitonia Excelsa

Plant of the Month - February by Allan Carr Alphitonia excelsa soap tree Pronunciation: al-fit-OWN-ee-a ek-SELL-sa RHAMNACEAE Derivation: Alphitonia, from the Greek, alphiton – baked barley meal (referring to the red mealy matter around the seeds); excelsa, from the Latin, excelsus – elevated, lofty (referring to its tall habit). Chewed leaves (undersides) Buds, flowers, sugar ant Fruits, both green and mature There are about 20 Alphitonia species, mostly in tropical areas around the world with 7 or 8 extending to Australia. Description: A. excelsa is a tree to 18 m, sometimes smaller, that occurs in deep sands on forest edges in coastal and near coastal areas from northern Qld down into southern NSW. It is also found in northern WA and NT The bark is usually distinctively mottled with a variety of lichens. Young parts of the plant are covered in rusty hairs and smell of sarsaparilla when crushed. The common name comes from the ability to form a soapy froth when leaves are rubbed with wet hands. This is due to a high *saponin content. Bark Leaves to 150 mm x 55 mm are alternate, green above with an under surface of silvery- white with fine hairs. Their edges are slightly curled under and frequently show much damage after being eaten by various leaf chewing insects including caterpillars of the Small Green-banded Blue butterfly (Psychonotis caelius). Flowers are creamy-green, tiny, 5-petalled and borne in *axillary clusters from November to April. Fruits are dry, black, globular to 12 mm across with reddish -brown seeds inside. -

Alphitonia Excelsa (A

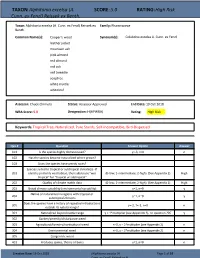

TAXON: Alphitonia excelsa (A. SCORE: 5.0 RATING: High Risk Cunn. ex Fenzl) Reissek ex Benth. Taxon: Alphitonia excelsa (A. Cunn. ex Fenzl) Reissek ex Family: Rhamnaceae Benth. Common Name(s): Cooper's wood Synonym(s): Colubrina excelsa A. Cunn. ex Fenzl leather jacket mountain ash pink almond red almond red ash red tweedie soaptree white myrtle whiteleaf Assessor: Chuck Chimera Status: Assessor Approved End Date: 19 Oct 2018 WRA Score: 5.0 Designation: H(HPWRA) Rating: High Risk Keywords: Tropical Tree, Naturalized, Pure Stands, Self-Incompatible, Bird-Dispersed Qsn # Question Answer Option Answer 101 Is the species highly domesticated? y=-3, n=0 n 102 Has the species become naturalized where grown? 103 Does the species have weedy races? Species suited to tropical or subtropical climate(s) - If 201 island is primarily wet habitat, then substitute "wet (0-low; 1-intermediate; 2-high) (See Appendix 2) High tropical" for "tropical or subtropical" 202 Quality of climate match data (0-low; 1-intermediate; 2-high) (See Appendix 2) High 203 Broad climate suitability (environmental versatility) y=1, n=0 y Native or naturalized in regions with tropical or 204 y=1, n=0 y subtropical climates Does the species have a history of repeated introductions 205 y=-2, ?=-1, n=0 n outside its natural range? 301 Naturalized beyond native range y = 1*multiplier (see Appendix 2), n= question 205 y 302 Garden/amenity/disturbance weed 303 Agricultural/forestry/horticultural weed n=0, y = 2*multiplier (see Appendix 2) n 304 Environmental weed n=0, y = 2*multiplier (see Appendix 2) n 305 Congeneric weed 401 Produces spines, thorns or burrs y=1, n=0 n Creation Date: 19 Oct 2018 (Alphitonia excelsa (A.