Working with CS Sherrington, 1918

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Summits of Modern Man: Mountaineering After the Enlightenment (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2013)

Bibliography Peter H. Hansen, The Summits of Modern Man: Mountaineering after the Enlightenment (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2013) This bibliography consists of works cited in The Summits of Modern Man along with a few references to citations that were cut during editing. It does not include archival sources, which are cited in the notes. A bibliography of works consulted (printed or archival) would be even longer and more cumbersome. The print and ebook editions of The Summits of Modern Man do not include a bibliography in accordance with Harvard University Press conventions. Instead, this online bibliography provides links to online resources. For books, Worldcat opens the collections of thousands of libraries and Harvard HOLLIS records often provide richer bibliographical detail. For articles, entries include Digital Object Identifiers (doi) or stable links to online editions when available. Some older journals or newspapers have excellent, freely-available online archives (for examples, see Journal de Genève, Gazette de Lausanne, or La Stampa, and Gallica for French newspapers or ANNO for Austrian newspapers). Many publications still require personal or institutional subscriptions to databases such as LexisNexis or Factiva for access to back issues, and those were essential resources. Similarly, many newspapers or books otherwise in the public domain can be found in subscription databases. This bibliography avoids links to such databases except when unavoidable (such as JSTOR or the publishers of many scholarly journals). Where possible, entries include links to full-text in freely-accessible resources such as Europeana, Gallica, Google Books, Hathi Trust, Internet Archive, World Digital Library, or similar digital libraries and archives. -

Book Reviews 1982

225 Book Reviews 1982 Compiled by Geoffrey Templeman DAL CAUCASO AL HIMALAYA. VITTORIO SELLA (Club Alpino Italiano/Touring Club Italiano, 1982, pp 239, profusely illustrated, 300 x 220mm, npq.) This magnificent volume has been graciously presented to the Club by Dr Ludovico Sella and inscribed'A souvenir of Vittorio Sella's long association with British mountaineering'. The definitive biography in English of Sella was written by our member, Ronald Clark, and published in 1948 under the title The Splendid Hills. It was reviewed at length in AJ L VII. In 1981, nearly 40 years after Sella's death, a much more detailed work has been produced under the aegis of the Italian Alpine Club and the Touring Club. This is stated to be the first comprehensive account'at least in Italy' of the great man and his work. This is certainly true of the text with its detailed history of the Sella family, and records of Sella's extensive Alpine travels in his earlier years, particularly his great winter ascents of the Matterhorn, Mont Blanc and Monte Rosa. The large illustrations, for the most part, as the title of the book suggests, are related to his travels beyond Europe, and thus his Alpine and Dolomite photographs are not as fully represented as in Clark's book. In 1879, after the premature death of his father, Vittorio was 'bought out' of the cavalry regiment in which he was serving, in order to train for his future responsibilities in the prosperous textile mills owned by the family. His father had been a keen photographer, and Vittorio acquired his large camera, and other equipment. -

The Modernisation of Elite British Mountaineering

The Modernisation of Elite British Mountaineering: Entrepreneurship, Commercialisation and the Career Climber, 1953-2000 Thomas P. Barcham Thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of De Montfort University for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Submission date: March 2018 Contents Abstract ................................................................................................................................................... 4 Acknowledgments ................................................................................................................................... 5 Table of Abbreviations and Acronyms .................................................................................................... 6 Table of Figures ....................................................................................................................................... 7 Chapter 1. Introduction .......................................................................................................................... 8 Literature Review ............................................................................................................................ 14 Definitions, Methodology and Structure ........................................................................................ 29 Chapter 2. 1953 to 1969 - Breaking a New Trail: The Early Search for Earnings in a Fast Changing Pursuit .................................................................................................................................................. -

Physiological Society Template

Annual report and accounts for year ended 31 December 2015 Company number: 323575 Registered charity: 211585 Annual report and accounts Company No. 323575 Contents 1 Report of the Trustees 1 1.1 Charitable objects of The Society 1 1.2 Message from our President and Interim CEO 2 1.3 Treasurer's statement 4 1.4 Public benefit statement 6 1.5 Structure, governance and management 7 1.6 Publications 10 1.7 Events 16 1.8 Membership 20 1.9 Education and Outreach 23 1.10 Policy 26 1.11 Signing of report 29 2 Independent auditor’s report 30 3 Statement of financial activities 32 4 Balance sheet 33 5 Statement of cash flows 34 6 Accounting policies 35 7 Notes to the financial statement 38 7.1 Income from charitable activities 38 7.2 Income from investments 38 7.3 Analysis of expenditure 38 7.4 Analysis of support and governance costs 39 7.5 Analysis of grants 39 7.6 Staff costs 40 7.7 Related party transactions 41 7.8 Tangible fixed assets 42 Annual report and accounts Company No. 323575 7.9 Investments 42 7.10 Debtors 43 7.11 Creditors 43 7.12 Analysis of net funds 44 7.13 Reconciliation of net movement in funds to net cash flow from operating activities 44 7.14 Analysis of cash and cash equivalents 45 7.15 Comparative SOFA per FRS 102 (SORP 2015) 45 8 Standing information 46 This is the Trustees’ Annual Report and Accounts for the year ended 31 December 2015 for The Physiological Society. -

J Gareth Jones Summary Jan 2013

BEHIND THE SCENES AT CARDlFF'S INSTITUTE OF PHYSIOLOGY 1920-61 Professor J Gareth Jones. Woodlands, Rufforth. York YO23 3QF. Thomas Graham Brown (1882-1965), a pioneer in spinal control of locomotion, came to Cardiff as Professor of Physiology in 1920, was Dean of the Medical School 1924-1926 and elected FRS in 1927 (1). Throughout the 1920s he was involved in a bitter conlict to implement Haldane’s 1918 Royal Commission recommendation that the medical school should become an independent institution within the University of Wales, but strongly opposed by University College, Cardiff (UCC). Into this Oire was thrown the fat of the InOirmary consultants who launched a campaign that closed the Clinical School from 1928-1929. Exhausted by years of acrimony, the clinical departments formed an independent Welsh National School of Medicine but the pre-clinical departments remained within UCC. TGB fought on to prevent this, petitioning the Privy Council, but this was in vain and his published research stopped. Instead, during the interwar years, TGB became famous as a mountaineer, pioneering three of the formidable routes to the summit of Mont Blanc from the Brenva glacier described in his fascinating book (2). But this precipitated a bitter and life long feud with his fellow climber FS Smythe (3). He co-led the 1936 UK-USA Nanda-Devi (25,643 ft) expedition, the highest peak climbed by man until 1950 and described by Shipton as “The Finest mountaineering achievement ever performed in the Himalayas”. Among TGB’s Institute associates were Nam Surman, trained in Oxford by TGB’s old boss and Nobel Laureate, Sir Charles Sherrington, Ivan de Burgh Daly, Sir Tudor Thomas, John Shaxby, Alben Hemingway, Frank Beswick and Stuart Stone. -

Old Ipswichian Journal

The journal of the Old Ipswichian Club Old Ipswichian Journal The Journal of the Old Ipswichian Club | Issue 7 Summer 2016 In this issue Club news Features Members’ news Births, marriages, deaths and obituaries OI Club events School news From the archives Programme of events Page Content 01 Member Leavers 2015 Member Leavers 2015 The journal of the Old Ipswichian Club Garnham Lauren Lo Thomas Patten Louis Life Members Gemmel Molly MacDonald Hamish Phillips Olivia Hewitt Edie Mahoney Elizabeth Raven Max Year 13 Hacker Abby Rule Cameron Hopkins Connie Marfoh-Gillings Laurence Watkins Rupert Hare Beth Rumsey Megan James Henry Morgan Tom Wilson James Sonia Abbie Angel Fergus Head Christopher Seifert Henry Jamieson Parsons Aulsebrook Gigi Hopkins Sam Sexton Sophie Badman Harry Hoskyns Chandos Shaikly Jonathan Bailey Thomas Hoskyns Wilf Sinha Kanishk Barker Dominic Howlett Olivia Taylor Shannon Associate Members Beavan Harry Huang Jeremy Temple McCune Nicholas Betterton Moné Hughes Thomas Wagland Isaac Sam Year 11 Bolton William Keeble Tim Wainer Robert Anderson Hollie Bowditch Lily Lawson Oliver Ward Ollie Beeson Charlie Oliver Buckley Liam Lee Jackie White Tom Culley Bolton Will Polly Burn James Livingstone Angus Wilding Josh Dudley Chiddicks Thomas Juliette Cattermole Ben Lo Rebecca Woods Ballard Alexandra France Clarke Charlie Blake Chang Ho Louch Harry Wyer Emily Kenworthy Dean Oliver James Conway Alice Macdonald Lily Yap Krystal King Gray Christopher Vanessa Cowie Sam Marshall Jess Yeap Joo Yee Lee Leung Claude Bethan Cubitt Penny -

The Potential of Our Uplands Irish Uplands Forum Report

Winter 2019 €3.95 UK£3.40 ISSN 0790 8008 Issue 132 The potential of our uplands Irish Uplands Forum report The Nativity Trail Walking in Mary and Joseph’s footsteps www.mountaineering.ie BA Hons in Geography and Outdoor Education Learning Through Adventure www.gmit.ie/outdoor-education 2 Irish Mountain Log Winter 2019 A Word from the edItor ISSUE 132 The Irish Mountain Log is the membership magazine of Mountaineering Ireland. The organisation promotes the interests of hillwalkers and climbers in Ireland. Mountaineering Ireland Welcome Mountaineering Ireland Ltd is a company limited by guarantee and éad míle fáilte! Christmas is here registered in Dublin, No 199053. again! Well, in fact it seems to have Registered office: Irish Sport HQ, been with us for some time now, National Sports Campus, with the seasonal decorations on Blanchardstown, Dublin 15, Ireland. C Tel: (+353 1) 625 1115 display in the streets, etc. Weather We are always looking for Fax: (+353 1) 625 1116 permitting, when we get to the Christmas articles❝ from our members [email protected] break, it is always a good time to get out www.mountaineering.ie into the hills to try to clear our heads and to to include in the magazine. counter the excesses that seem to go with Hot Rock Climbing Wall the Christmas celebrations. Tollymore Mountain Centre the AGM for my work on the Irish Mountain Bryansford, Newcastle It has been another good year for County Down, BT33 0PT Mountaineering Ireland. The CEO Murrough Log. It was a great surprise to me but also a great honour. -

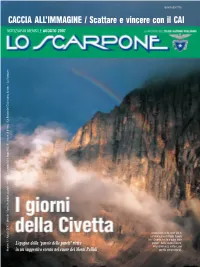

LO SCARPONE 08 6-07-2007 18:27 Pagina 1

LO SCARPONE 08 6-07-2007 18:27 Pagina 1 ISSN 1590-7716 CACCIA ALL’IMMAGINE / Scattare e vincere con il CAI NOTIZIARIO MENSILE AGOSTO 2007 a del Club Alpino Italiano - Lo Scarpone Arcobaleno sulla nord est in un’immagine di Paola Favero (da “Civetta, tra le pieghe della L’epopea della “parete delle pareti” rivive parete” della stessa Favero, Priuli&Verlucca editori, per gentile concessione). Numero 8 - Agosto 2007 Mensile Sped. in abbon. postale 45% art. 2 comma 20/b legge 662/96 Filiale di Milano La Rivist in un suggestivo evento nel cuore dei Monti Pallidi LO SCARPONE 08 6-07-2007 18:27 Pagina 2 Le nuove T-shirt del CAI CARATTERISTICHE: le nostre T-shirt girocollo, modello unisex, a mezze maniche, con disegno esclusivo del CAI, logo e scritta “Club Alpino Italiano”, confezionate singolarmente, sono tutte realizzate in 100% cotone di alta qualità (160 gr/m2) e fanno parte della linea E-cotton. E-cotton è la maglietta in cotone di commercio EquoSolidale, realizzata da organizzazioni umanitarie impegnate nello sviluppo economico di aree svantaggiate. COLORI: Blu cobalto, Ecru, Nero, Verde bottiglia, Grigio TAGLIE DISPONIBILI: S, M, L, XL, XXL PREZZO UNITARIO: € 10,00 riservato ai soci CAI, € 15,00 non soci (prezzi IVA inclusa) COME ORDINARLE: le T-shirts possono essere richieste direttamente in Sezione (le Sezioni possono scaricare il modulo d'ordine dal sito www.cai.it) Iniziativa a cura della Sede Centrale del CAI LO SCARPONE 08 6-07-2007 18:27 Pagina 3 SOMMARIO In questo numero Fondato nel 1931 - Numero 8 - Agosto 2007 4 DOLOMITI 21 ALPINISTI Direttore responsabile: Pier Giorgio Oliveti Sotto lo sguardo della Civetta I Rondi tornano a volare Direttore editoriale: Gian Mario Giolito Coordinamento redazionale: Roberto Serafin di Paola Favero Segreteria di redazione: Giovanna Massini e-mail: [email protected] oppure [email protected] 22 INCONTRI CAI Sede Sociale 10131 Torino, Monte dei Capuccini. -

Mountaineer Henkil㶠Lista

Mountaineer Henkilö Lista UkyÅ Katayama https://fi.listvote.com/lists/person/uky%C5%8D-katayama-171543 Richard Bass https://fi.listvote.com/lists/person/richard-bass-1209611 Fritz Wintersteller https://fi.listvote.com/lists/person/fritz-wintersteller-186303 Radek JaroÅ¡ https://fi.listvote.com/lists/person/radek-jaro%C5%A1-1717323 Jim Whittaker https://fi.listvote.com/lists/person/jim-whittaker-1383689 Angelo Dibona https://fi.listvote.com/lists/person/angelo-dibona-535859 Hansjörg Auer https://fi.listvote.com/lists/person/hansj%C3%B6rg-auer-1583841 Karl Prusik https://fi.listvote.com/lists/person/karl-prusik-113958 Mikael Reuterswärd https://fi.listvote.com/lists/person/mikael-reutersw%C3%A4rd-6164382 Harald Berger https://fi.listvote.com/lists/person/harald-berger-1511385 Steve House https://fi.listvote.com/lists/person/steve-house-949892 Martin MinaÅ™Ãk https://fi.listvote.com/lists/person/martin-mina%C5%99%C3%ADk-12035791 Ilmar Priimets https://fi.listvote.com/lists/person/ilmar-priimets-29419772 Charlie Porter https://fi.listvote.com/lists/person/charlie-porter-5085405 Armando Aste https://fi.listvote.com/lists/person/armando-aste-328448 Hamish MacInnes https://fi.listvote.com/lists/person/hamish-macinnes-3126469 Alfred Amstad https://fi.listvote.com/lists/person/alfred-amstad-2644637 Jean Arlaud https://fi.listvote.com/lists/person/jean-arlaud-3170414 Gian Carlo Grassi https://fi.listvote.com/lists/person/gian-carlo-grassi-2059820 Abele Blanc https://fi.listvote.com/lists/person/abele-blanc-318555 Fredrik Sträng https://fi.listvote.com/lists/person/fredrik-str%C3%A4ng-5499537 -

Josef Knubel

JOSEF KNUBEL BY ALFRED ZURCHER (Translated by Hugh Merrick) OSEF Knubel died in hospital at Visp on May 31, rg6r, following an abdominal operation. His fellow guides bore the slight burden of his body to his grave at St. Niklaus. For' Little J. ',as Young called him, was never a heavy man; and the cares of his last years of en forced idleness had eroded rather than filled out his small frame. Yet, with what an immeasurable weight did J osef 's passing fall upon his friends; how suddenly was his towering stature as a man made mani fest; how gigantic were seen to be the achievements of his long life .... As Josef Knubel's 'Herr' through many years and his friend to the last day, I hope I may be permitted in these pages to cast a last short glance over the life and triumphs of this unique character among guides. J osef Knubel, the son of a guide and wood-cutter, Peter Knubel, was born at St. Niklaus on March 2, r88r. His childhood days were no different from those of his contemporaries. He was soon involved in all the work in the fields and in the barn, on the alp and in the forest; when minding the goats and wielding a scythe on the slopes he very soon showed the toughness, endurance, self-reliance and perfect security of movement, on no matter what terrain, which were to be lifelong characteristics. His mountaineering activities, too, began early in life. When he was only fifteen, his father allowed him to accompany him and a client on a climb of the Matterhorn. -

In Memoriam 229

• IN MEMORIAM 229 • IN MEMORIAM LESLIE VICKERY BRYANT 1905-1957 IN December I957, by the tragic death of L. V. (Dan) Bryant in a motoring accident, the Club lost one of its stout band of New Zealand members, and the N.Z. Alpine Club one of its best-known mountaineers. As a result of his two periods of study in England, with vacation climb ing here and on the Continent, and particularly through his inclusion in the 1935 Everest Reconnaissance Expedition, he was known to many members of the Club ; these, as well as many others with mountain interests who knew him, will feel that by his passing, at the age of 52, mountaineering has suffered a great loss. Bryant chose secondary school teaching as a career and, after graduating Master of Arts at the Auckland University College, he took his first appointment at the New Plymouth Boys' High School in I 927. Here his proximity to l\tlount Egmont enlivened an interest in climbing. He introduced many boys from his school to the sport through his organised trips on the mountain and took more than ISO of them to the summit of this fine peak. Then from I 930 his teaching appointments were mainly in the South Island first at Waitaki Boys' High, then at Southland Boys' High, back to Waitaki as senior house master and then as first assistant at the Timaru Technical College. In I 946 he became principal of the Pukekohe High School, near Auckland, and filled that position, with credit to himself and great benefit to the school, until his passing on the eve of the annual prize-giving ceremony, for which he had prepared one of his typically thoughtful addresses. -

Meno Fragili, Più Forti

La rivista del Club alpino italiano dal 1882 OTTOBRE 2020 € 3,90 egge 662/96 Filiale di Milano. Prima immissione il 27 settembre 2020 settembre il 27 immissione Prima 662/96 Filiale di Milano. egge MENO FRAGILI, PIÙ FORTI 3,90. Rivista mensile del Club alpino italiano n. 97/2020. Poste Italiane Spa, sped. in abb. Post. - 45% art. 2 comma 20/b - l 20/b 2 comma - 45% art. Post. in abb. sped. Spa, Italiane Poste 97/2020. mensile n. Rivista del Club alpino italiano 3,90. € Montagnaterapia, la risorsa per il corpo e per la mente Montagne360. Ottobre 2020, 2020, Ottobre Montagne360. GRISPORT PRONTE PER OGNI SFIDA. Mod. 12833 www.grisport.com A WORLD TO DISCOVER EDITORIALE orizzonti e orientamenti Ritrovarsi in assemblea con rispetto e prudenza di Vincenzo Torti* Socie e Soci carissimi, la miglior garanzia di corretto svolgimento di ogni fase. ho già avuto modo di esprimere la più viva gratitudine Purtroppo mancheranno i momenti conviviali che rap- per la vostra confermata appartenenza in un momento presentavano un’occasione di conoscenza reciproca e di così delicato per ciascuno e per la collettività tutta: è scambio di opinioni tra delegati e tra questi e coloro che stato un po’ come stringerci intorno ad un riferimento ricoprono cariche centrali, ma il maggiore spazio che comune da tenere ben fermo, proprio quando incertezza verrà dato proprio agli interventi dei delegati consentirà, e precarietà vorrebbero sopraffarci. comunque, di valorizzare al meglio la sede assembleare Anche per questo, dopo la ripresa sia dell’attività in per fornire indicazioni, proposte, valutazioni che possa- montagna, che delle Sezioni, sia pure con tutte le atten- no indirizzare al meglio le scelte e, quindi, l’andamento zioni del caso e nel costante rispetto di quelle che si sono del nostro Sodalizio in questa particolare situazione.