Sir Winston Churchill

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

First Lady: the Life and Wars of Clementine Churchill Free Ebook

FREEFIRST LADY: THE LIFE AND WARS OF CLEMENTINE CHURCHILL EBOOK Sonia Purnell | 400 pages | 14 May 2015 | Aurum Press Ltd | 9781781313060 | English | London, United Kingdom Biography of Clementine Churchill, Britain's First Lady First Lady is a bold biography of a bold woman; at last Purnell has put Clementine Churchill at the centre of her own extraordinary story, rather than in the shadow of her husband's.' 'From the influence she wielded to the secrets she kept, a new book looks at the extraordinary role of Winston Churchill's wife Clementine who proved that behind. First Lady: the Life and Wars of Clementine Churchill, review: 'fascinating account of an under appreciated woman' Geoffrey Lyons reviews Sonia Purnell’s enthralling new biography of one of Britain’s most misunderstood figures. Keeping silent was, Purnell argues, Clementines most decisive and courageous action of the war. Anne Sebba is the author of American Jennie, The Remarkable Life of Lady Randolph Churchill (WW Norton ) and is currently writing Les Parisiennes: how Women lived, loved and died in Paris from for publication in First Lady: The Life and Wars of Clementine Churchill First Lady: the Life and Wars of Clementine Churchill, review: 'fascinating account of an under appreciated woman' Geoffrey Lyons reviews Sonia Purnell’s enthralling new biography of one of Britain’s most misunderstood figures. Royal Oak lecturer Sonia Purnell’s new book, “First Lady: the Life and Wars of Clementine Churchill,” is out to rave reviews. Examining Clementine’s role in some of the critical events of the 20th century, Purnell retells a history that has largely marginalized Sir Winston’s wife. -

Obituary LIONEL ERNEST HOWARD WHITBY, Kt., C.V,Q., M.C., M.A., M.D., F.R.C.P., Hon.D.Sc.(Toronto), Hon.LL.D.(Glasg.), -Hon.M.D.(Louvain), D.P.H

J R Army Med Corps: first published as 10.1136/jramc-103-02-09 on 1 April 1957. Downloaded from 102 Obituary LIONEL ERNEST HOWARD WHITBY, Kt., C.V,Q., M.C., M.A., M.D., F.R.C.P., Hon.D.Sc.(Toronto), Hon.LL.D.(Glasg.), -Hon.M.D.(Louvain), D.P.H. THE facilities provided today by the National Blood Transfusion Service make it difficult to appreciate the trouble a transfusion entailed less than twenty-five years ago. Probably the greatest single factor responsible for the change was the Army Transfusion Service, developed during the last war. The inspiration and organizing genius behind this pioneer service, which has teen taken as a pattern by so many others since, was Brigadier Sir Lionel Whitby, whose death occurred on November 24th, 1956, after an operation, at the age of 61. By his death the Army has lost one of its most eminent Honorary Consultants and a staunch friend. Lionel Ernest Howard Whitby was born on May 8th, 1895, and was educated at Bromsgrove School and Downing College, Cambridge. He had won an open scholarship but before taking it up, joined the Royal Fusiliers on the outbreak . of the First World War. The following year he was commissioned in the Royal guest. Protected by copyright. West Kent Regiment and in 1917 was awarded the M.C. for gallantry at Pas schendaele. In 1918, when a machine-gun officer with the rank of Major, he was severely wounded and had a leg amputated near the hip. After his recovery he studied medicine at Cambridge and at the Middlesex Hospital where he was a scholar and a prizeman, qualifying in 1923. -

Catalogue 244: the Churchills 1 15

The Churchills Catalogue 244 July 2021 ABOUT THIS CATALOGUE Most of the books in this catalogue are from the private library of the late The Hon. David Levine AO RFD QC. Most carry his bookplate or book label, usually affixed to the upper pastedown or upper free endpaper. TERMS AND CONDITIONS OF SALE Unless otherwise described, all books are in the original cloth or board binding, and are in very good, or better, condition with defects, if any, fully described. Our prices are nett, and quoted in Australian dollars. Traditional trade terms apply. Items are offered subject to prior sale. All orders will be confirmed by email. PAYMENT OPTIONS We accept the major credit cards, PayPal, and direct deposit to the following account: Account name: Kay Craddock Antiquarian Bookseller Pty Ltd BSB: 083 004 Account number: 87497 8296 Should you wish to pay by cheque we may require the funds to be cleared before items are sent. GUARANTEE As a member or affiliate of the associations listed below, we embrace the time-honoured traditions and courtesies of the book trade. We also uphold the highest standards of business principles and ethics, including your right to privacy. Under no circumstances will we disclose any of your personal information to a third party, unless your specific permission is given. TRADE ASSOCIATIONS Australian and New Zealand Association of Antiquarian Booksellers [ANZAAB] Antiquarian Booksellers’ Association [ABA(Int)] International League of Antiquarian Booksellers [ILAB] Australian Booksellers Association REFERENCES CITED Cohen: Bibliography of the Writings of Sir Winston Churchill. By Ronald Cohen. In three volumes. Thoemmes Continuum, London, 2006. -

THE CHURCHILLIAN Churchill Society of Tennessee 1St Summer Edition 2020

THE CHURCHILLIAN Churchill Society of Tennessee 1st Summer Edition 2020 Churchill Rising! "Come then, let us go forward together with our united strength." On Friday May 10, 1940 Winston S Churchill becomes Prime Minister of Great Britain. The Churchillian Page 1 THE CHURCHILL SOCIETY OF TENNESSEE Patron: Randolph Churchill Board of Directors: Executive Committee: President: Jim Drury Vice President Secretary: Robin Sinclair PhD Vice President Treasurer: Richard Knight Esq Comptroller: The Earl of Eglinton & Winton, Hugh Montgomery - Robert Beck Don Cusic Beth Fisher Michael Shane Neal - Administrative officer: Lynne Siesser Webmaster: Martin Fisher - Past President: Dr John Mather - Sister Chapter: Chartwell Branch, Westerham, Kent, England - Contact information: Churchillian Editor: Jim Drury www.churchillsocietytn.org Churchill Society of Tennessee PO BOX 150993 Nashville, TN 37215 USA 615-218-8340 The Churchillian Page 2 Inside this issue of the Churchillian Page 4. Letter from the President Page 6. Churchill Speech Series: ‘blood, toil, tears and sweat’ May 1940 Page 9. Sir Winston Churchill Fractures His Hip In The South Of France by Allister Vale MD and John Scadding OBE Page 11. Recollections of nursing Sir Winston Churchill by Gill Morton Page 18. The Friendship Between The Hamiltons And The Churchills by Celia Lee Page 26. Book Announcments: Winston Churchill’s Illnesses 1886-1965 By Allister Vale MD and John Scadding OBE Jean Lady Hamilton Diaries Of A Soldier’s Wife By Celia Lee Page 30. Resources Page The Churchillian Page 3 From the President Dear Members, I hope you are all doing well as we move through these challenging times. It is always good to have interests that divert from the day to day and uplift our minds and spirits. -

By Stan/Ey French the History of DOWNING COLLEGE CAMBRIDGE

The History of DOWNING COLLEGE CAMBRIDGE by Stan/ey French The History of DOWNING COLLEGE CAMBRIDGE by Stan/ey Fre11ch DOWNING COLLEGE ASSOCIATION 1978 CONTENTS CHAPTER I THE MARRIAGE 7 CHAPTER 2 UNBREAKABLE BOND 15 CHAPTER 3 THE OLD MAID 23 CHAPTER4 THE GRASS WIDOWER 31 CHAPTER 5 THE LAST OF THE LINE 43 CHAPTER 6 INTO CHANCERY 51 CHAPTER 7 WICKED LADY 59 CHAPTER 8 INDEFATIGABLE CHAMPION 67 CHAPTER 9 UPHILL ALL THE WAY 77 CHAPTER 10 THE IDEAL AND THE REAL 82 CHAPTER 11 FRANCIS ANNESLEY AND HIS COLLEAGUES 89 CHAPTER 12 OPENED FOR EDUCATION 95 CHAPTER 13 TROUBLE IN ARCADY Ill CHAPTER 14 STAGNATION AND PROGRESS 124 CHAPTER 15 ACHIEVEMENT 132 THE FOUNDER'S FAMILY TREE 142 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS 143 PRINCIPAL SOURCES 144 ILLUSTRATIONS 1. Cover: Sir George Downing, third baronet, founder of Downing College, Cambridge. (From a miniature owned by Capt. G. D. Bowles.) 2. Frontspiece: Francis Annesley, Master 1800-1812 without whose persistence Downing College would not have been founded. (From the copy in the Senior Combination Room, Downing College of the portrait by A. Hickel at Reading Town Hall.) 3. Sir George Downing, first baronet, founder of the Downing fortune. (From a copy of the portrait at Harvard.) 13 .,. 4. Lady {Mary) Downing, n~e Forester, wife of the third baronet. (From the portrait at Willey Hall; photograph given by the late Lord Forester.) 25 5. Lady (Margaret) Downing, nle Price, wife of the fourth baronet. {From the portait in Downing College Hall.) 63 6. Downing College as it might have been. (From an engraving at Downing College, of an illustration in Le Keux, Cambridge, 1862.) 85 7. -

The Private Letters of Sir Winston and Lady Churchill Free Download

SPEAKING FOR THEMSELVES: THE PRIVATE LETTERS OF SIR WINSTON AND LADY CHURCHILL FREE DOWNLOAD Sir Winston S. Churchill,Baroness Clementine Spencer- Churchill,Mary Soames | 768 pages | 05 Aug 1999 | Transworld Publishers Ltd | 9780552997508 | English | London, United Kingdom Clementine Churchill Subscription failed, please try again. Sensible man you say Share at. Community Reviews. Preference and Feature cookies allow our website to remember choices you make, such as your language preferences and any customisations you make to pages on our website during your visit. Speaking for Themselves is not only an important historical document, it is a love story and an intimate, charming and often surprising insight into one of the century's most successful marriages. These cookies may be set by us or by third-party providers whose services we have added to our pages. Puffin Ladybird. Kerensa Jennings rated it it was amazing Feb 12, Episode 3 of 10 Tragedy strikes and more loneliness follows. Here are harrowing first-hand accounts from the battlefields ofreflections on political triumphs and upsets, as well as domestic minutiae, foreign travel, revelations of social scandals and, above all, words of mutual support and encouragement that span the career of one of Britain's most revered statesmen. Commercial advertising. Mary Soames is perfectly placed to select and comment upon this vast collection of letters. Rebecca Jaramillo rated it it was amazing Feb 11, Bookseller Inventory ST Seller Inventory GRD What a wonderful collection of letters from such a different era. Narrated by Helen Bourne. One presumes it must have taken a certain type of woman to be married to Winston, and this "certain type of woman" sure shines through these pages as much as hi Meticulously edited, compiled and Speaking for Themselves: The Private Letters of Sir Winston and Lady Churchill, this deeply personal record must have been a very emotional journey for a daughter to do of her parents. -

Clementine Churchill: the Biography of a Marriage Free

FREE CLEMENTINE CHURCHILL: THE BIOGRAPHY OF A MARRIAGE PDF Mary Churchill Soames | 621 pages | 07 Aug 2003 | Mariner Books | 9780618267323 | English | Boston, MA, United States Clementine Churchill: The Biography of a Marriage - Mary Soames - Google книги And, according to newly discovered testimony from a key witness who has just come forward as well as surviving members of her familytheir affair lasted for a period of around four years. And why does it matter? She was born Doris Delevingne in and married Viscount Castlerosse inthough the Clementine Churchill: The Biography of a Marriage was in effect over the following year. Clementine Churchill: The Biography of a Marriage also, when one considers how her life panned out see belowrather sad. Colville was assistant private secretary to three prime ministers: Neville Chamberlain, Churchill and Clement Attlee. He was also private secretary to Princess Elizabeth, now the Queen, from to Colville made a recording in for the Churchill archives at Churchill College, Cambridge, but it appears no historian or biographer listened to the entire tape — until now. He had a brief Clementine Churchill: The Biography of a Marriage with Doris Castlerosse. I wonder shall we meet again next summer. The timeline means it was before Churchill became Prime Minister but they did meet at least once when he was wartime leader — in the US, where Lady Castlerosse was an unhappy exile living in New York in So in he secured her passage home — quite an ask considering the war was on — and was deeply concerned about a painting of his of her that she had in her possession and that was rather suggestive. -

First Lady: the Life and Wars of Clementine Churchill

Published on Reviews in History (http://www.history.ac.uk/reviews) First Lady: The Life and Wars of Clementine Churchill Review Number: 1932 Publish date: Thursday, 12 May, 2016 Author: Sonia Purnell ISBN: 9781781313060 Date of Publication: 2015 Price: £25.00 Pages: 400pp. Publisher: Quarto Publishing Group UK Publisher url: http://www.quartouk.com/products/9781781313060/9781781313060/First-Lady.html Place of Publication: London Reviewer: Bradley Hart In late 1909, a suffragette attacked the Asquith government’s youthful President of the Board of Trade, slashing his face with a whip as he prepared to give a speech in Bristol station. Briefly stunned, he fell toward the station’s tracks at the same moment a train pulled out of the station. Leaping into action as others looked on in horror at the unfolding scene, it was the young politician’s wife who pulled him back – literally by his coat tails – from almost certain death. Had she failed to react so quickly that morning, the name Winston Churchill would likely be known to only a few historians of the early 20th century. Clementine Churchill’s intervention not only saved her husband’s life but, it is tempting to say, likely carried far-reaching consequences for the course of the country’s future. Remove Churchill from the political scene in 1909 and it is at least conceivable – if not substantially more likely – that Britain in 1940 would reach an accommodation with Hitler’s Germany and the world map would look very different today. Anecdotes of this type, and the resulting counterfactuals that are difficult to resist considering, are effectively the raison d'être for Sonia Purnell’s new biography of Clementine Churchill (First Lady: The Life and Wars of Clementine Churchill). -

Jean, Lady Hamilton (1861-1941) Diaries of a Soldier’S Wife

THE FRIENDSHIP BETWEEN THE HAMILTONS AND THE CHURCHILLS by Celia Lee author of: JEAN, LADY HAMILTON (1861-1941) DIARIES OF A SOLDIER’S WIFE General Sir Ian Hamilton wrote: “… nobody, not even Lord Bobs in all his glory, has touched my life at so many points as Winston Churchill.” Lord Bobs was the Hamiltons’ nick-name for Frederick, Lord Roberts, Commander-in-Chief of the British Army in India. Miss Jean Muir, later Lady Hamilton, on her wedding day, Calcutta, India, 1887. Portrait by her great-niece, Mrs Barbara Kaczmarowska Hamilton. 1 Miss Jean Muir on her wedding morning 1887. By kind permission of Mr Ian Hamilton. Photo enhancement, Mr John David Olsen. 2 The little-known relationship between General Sir Ian Hamilton and his wife Jean, Lady Hamilton, with Winston and Clementine Churchill, comes to the fore in JEAN, LADY HAMILTON (1861-1941) DIARIES OF A SOLDIER’S WIFE, pub. Pen & Sword, that is written from the actual diaries by Celia Lee. The drawing room of the Hamiltons’ bungalow, Simla, India. Ian Hamilton is relaxing on a sofa reading a book. Photo by kind permission of his great nephew, Mr Ian Hamilton. Miss Jean Muir, daughter of the Scottish millionaire, Sir John Muir, and Margaret nee Kay, whose father was a partner in the tea manufacturing business of James Finlay & Co., married the penniless but brilliant soldier, Major Ian Hamilton. The wedding was a high society affair in St. Paul’s Cathedral, Calcutta 1887, followed by a lavish wedding reception. Afterwards the young couple were whisked away on the viceregal motor-launch to Lord William Beresford's villa in the lovely, romantic surroundings of Barrackpore, where they began their honeymoon. -

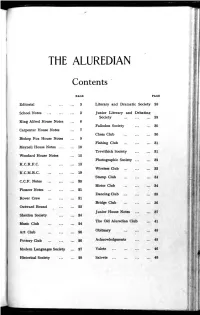

The Aluredian

THE ALUREDIAN Contents · PAGE PAGE Editorial 3 Literary and Dramatic Society 28 School Notes 3 junior Literary and Debatin~ Society 29 King Alfred House Notes 6 Fallodon Society 30 Carpenter House Notes 7 Chess Club 30 Bishop Fox House Notes 9 Fishing Club 31 Meynell House Notes ... 10 Trevithick Society 31 Woodard House Notes 12 Photographic Society 32 K.C.R.F.C. 13 Wireless Club 83 K.C.M.R.C. 19 Stamp Club 34 C.C.F . Notes 20 Motor Club 34 Pioneer Notes 21 Dancing Club 35 Rover Crew 21 Bridge Club 36 Outward Bound 22 Junior House Notes 37 Sheldon Society 24 The Old Aluredian Club u Music Club 24 Obituary Art Club 26 45 Pottery Club 26 Acknowledgments 45 Modem Languages Society 27 Valete 46 Historical Society 28 Salvete 48 THE ALUREDIAN EDITOR : J. H. CATLIN. SuB-EDITORs: A. J. HOLLAND, R. J. A. ABRAHAM. VoL. XXVIII. No . 6. FEBRUARY, 1957. Editorial HE Editorial of a magazine has in past centuries often been the place T where the Editor took the chance of explaining to readers what an excellent Magazine they were about to read. Here we do not wish to do only this, but to thank all our contributors for their work, without which the Magazine would obviously not appear. We would also like to re mind any would-be writers of original compositions, either verse or prose, that although it is not usual to publish original works in the Michaelmas Term, it is never too soon to start thinking of a contribution to the Lent and Summer issue. -

WINSTON CHURCHILL BECOMES PRIME MINISTER Winston Emerged Strongly from the Debate in the House of Commons on 7Th and 8Th May 1940

THE CHURCHILLIAN Churchill Society of Tennessee February 2019 -Special Edition - WHY CLEMENTINE, BARONESS SPENCER CHURCHILL IS DESERVING OF A TARTAN IN HER NAME By Celia Lee The "Clementine Churchill" tartan was first conceived in early 2018 as the result of a conversation between Mr. Randolph Churchill, great-grandson of Clementine, Baroness Spencer Churchilli and Pipe Major Jim Drury, President of the Churchill Society of Tennessee. The conversation began with a question. Did the International Churchill Society have its own tartan? Randolph responded it did not. He then suggested that whatever design was chosen it should have the colour of “marmalade” (gold) as a token of respect to his great-grandmother, The Churchillian Page 1 Clementine. From that point forward the new tartan pattern would be called “Clementine Churchill”. Various elements of Winston and Clementine’s life are represented in the tartan’s colours. The light and dark blues represent the RAF and Royal Navy. The grey background with black and white pinstripe alludes to the style business suit often worn by members of Parliament. However, the marmalade strip is perhaps the strongest element in the pattern and pulls the whole design together. That would be Clementine, Baroness Spencer Churchill. Pipe Major Jim Drury wearing the “Clementine Tartan” for the first time at the 35th Annual Conference of the International Churchill Society, Williamsburg VA, November 2018. The tune being played is “LTC Winston S. Churchill 6th Royal Scots Fusiliers 1916”. - Photo by Professor Allister Vale MD The Churchillian Page 2 Clementine Churchill’s efforts, both in her support of her husband Sir Winston Churchill, and her service to the nation is well worthy of such a tribute. -

Our Blood Your Money

Our Blood Your Money The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Hedley-Whyte, John, and Debra R. Milamed. 2013. “Our Blood Your Money.” The Ulster Medical Journal 82 (2): 114-120. Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:11877112 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA Ulster Med J 2013;82(2):114-120 Medical History Our Blood Your Money John Hedley-Whyte, Debra R. Milamed Accepted 26 July 2012 SUMMARY Dublin-born and Yale-trained Joseph Eastman Sheehan, Lord Nuffield’s choice for Professor of Plastic and Reconstructive On June 3, 1939, Donegal-born James C. Magee was Surgery5. Elósegui’s Nationalist Blood Transfusion Service appointed U.S. Army Surgeon General by President Franklin transfused an estimated 25,000 times before Franco’s victory6. Delano Roosevelt. On May 31, 1940, Magee appointed Professor Walter B. Cannon of Harvard University as Chairman of the U.S. National Research Council Committee on Shock and Transfusion. In 1938 Brigadier Lionel Whitby was appointed Director of an autonomous U.K. Army Blood Transfusion Service (ABTS). Whitby thereupon appointed Professor John Henry Biggart, Professor of Pathology, Queen’s University, his Northern Ireland Head of Blood Transfusion and Blood Banking. Winston S. Churchill was aware that Biggart’s service would be responsible for the needs of the Allied Forces and later for the United States Forces in Northern Ireland.