A Linguistic Study of the Magic in Disney Lyrics

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

“A Whole New World” by Zayn Malik and Zhavia Ward

PROJECT (Professional Journal of English Education) p–ISSN 2614-6320 Volume 3, No. 4, July 2020 e–ISSN 2614-6258 AN ANALYSIS OF FIGURATIVE LANGUAGE USED IN THE LYRIC OF “A WHOLE NEW WORLD” BY ZAYN MALIK AND ZHAVIA WARD Siti Nursolihat 1, Evie Kareviati2 1 IKIP Siliwangi 2 IKIP Siliwangi 1 [email protected], 2 [email protected] Abstract Language is a tool of communication used by people anywhere and every time. Now days people commonly find a figurative language in daily life, for example in a lyric of song. Figurative language is a way to express an idea in implicit way. This research is trying to analyze the figurative languages which exist in the lyric of song “A Whole New World” and trying to find out its meaning by analyzing its contextual meaning. This is a descriptive qualitative research. The data instrument is the song lyric which taken from Genius website. The result showed that this song consist of some figurative languages, such as alliteration, simile, personification, metaphor, and hyperbole. Furthermore, the most figurative language used in the lyric is metaphor. It is highly relatable with the imaginative theme of the song itself. The contextual meaning of each figurative language is also explained based on the situation of the lyric. Keywords: Figurative Language, Song Lyric, Contextual Meaning INTRODUCTION Language is a tool of communication used by the people, orally or writing. Basic aim of language learning nowdays is communication and vocabulary plays an important role in conversation (Komorowska, 2005) as cited in Nurdiansyah, Asyid, & Parmawati (2019). -

Bono, the Culture Wars, and a Profane Decision: the FCC's Reversal of Course on Indecency Determinations and Its New Path on Profanity

Bono, the Culture Wars, and a Profane Decision: The FCC's Reversal of Course on Indecency Determinations and Its New Path on Profanity Clay Calvert* INTRODUCTION The United States Supreme Court has rendered numerous high- profile opinions in the past thirty-five years regarding variations of the word "fuck." Paul Robert Cohen's anti-draft jacket,' Gregory Hess's threatening promise, 23George Carlin's satirical monologue,3 and Barbara Susan Papish's newspaper headline 4 quickly come to mind. 5 These now-aging opinions address important First Amendment issues of free speech, such as protection of political dissent,6 that continue to carry importance today. It is, however, a March 2004 ruling * Associate Professor of Communications & Law and Co-director of the Pennsylvania Center for the First Amendment at The Pennsylvania State University. B.A., 1987, Communication, Stanford University; J.D. with Great Distinction and Order of the Coif, 1991, McGeorge School of Law, University of the Pacific; Ph.D., 1996, Communication, Stanford University. Member, State Bar of California. 1. Cohen v. California, 403 U.S. 15 (1971) (protecting, as freedom of expression, the right to wear ajacket emblazoned with the words "Fuck the Draft" in a Los Angeles courthouse corridor). 2. Hess v. Indiana, 414 U.S. 105, 105 (1973) (protecting, as freedom of expression, defendant's statement, "We'll take the fucking street later (or again)," made during an anti-war demonstration on a university campus). 3. FCC v. Pacifica Found., 438 U.S. 726 (1978) (upholding the Federal Communications Commission's power to regulate indecent radio broadcasts and involving the radio play of several offensive words, including, but not limited to, "fuck" and "motherfucker"). -

World Latin American Agenda 2016

World Latin American Agenda 2016 In its category, the Latin American book most widely distributed inside and outside the Americas each year. A sign of continental and global communion among individuals and communities excited by and committed to the Great Causes of the Patria Grande. An Agenda that expresses the hope of the world’s poor from a Latin American perspective. A manual for creating a different kind of globalization. A collection of the historical memories of militancy. An anthology of solidarity and creativity. A pedagogical tool for popular education, communication and social action. From the Great Homeland to the Greater Homeland. Our cover image by Maximino CEREZO BARREDO. See all our history, 25 years long, through our covers, at: latinoamericana.org/digital /desde1992.jpg and through the PDF files, at: latinoamericana.org/digital This year we remind you... We put the accent on vision, on attitude, on awareness, on education... Obviously, we aim at practice. However our “charisma” is to provoke the transformations of awareness necessary so that radically new practices might arise from another systemic vision and not just reforms or patches. We want to ally ourselves with all those who search for that transformation of conscience. We are at its service. This Agenda wants to be, as always and even more than at other times, a box of materials and tools for popular education. latinoamericana.org/2016/info is the web site we have set up on the network in order to offer and circulate more material, ideas and pedagogical resources than can economically be accommo- dated in this paper version. -

Summer Classic Film Series, Now in Its 43Rd Year

Austin has changed a lot over the past decade, but one tradition you can always count on is the Paramount Summer Classic Film Series, now in its 43rd year. We are presenting more than 110 films this summer, so look forward to more well-preserved film prints and dazzling digital restorations, romance and laughs and thrills and more. Escape the unbearable heat (another Austin tradition that isn’t going anywhere) and join us for a three-month-long celebration of the movies! Films screening at SUMMER CLASSIC FILM SERIES the Paramount will be marked with a , while films screening at Stateside will be marked with an . Presented by: A Weekend to Remember – Thurs, May 24 – Sun, May 27 We’re DEFINITELY Not in Kansas Anymore – Sun, June 3 We get the summer started with a weekend of characters and performers you’ll never forget These characters are stepping very far outside their comfort zones OPENING NIGHT FILM! Peter Sellers turns in not one but three incomparably Back to the Future 50TH ANNIVERSARY! hilarious performances, and director Stanley Kubrick Casablanca delivers pitch-dark comedy in this riotous satire of (1985, 116min/color, 35mm) Michael J. Fox, Planet of the Apes (1942, 102min/b&w, 35mm) Humphrey Bogart, Cold War paranoia that suggests we shouldn’t be as Christopher Lloyd, Lea Thompson, and Crispin (1968, 112min/color, 35mm) Charlton Heston, Ingrid Bergman, Paul Henreid, Claude Rains, Conrad worried about the bomb as we are about the inept Glover . Directed by Robert Zemeckis . Time travel- Roddy McDowell, and Kim Hunter. Directed by Veidt, Sydney Greenstreet, and Peter Lorre. -

Various Disney Classics Mp3, Flac, Wma

Various Disney Classics mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Pop / Children's / Stage & Screen Album: Disney Classics Country: US Released: 2013 Style: Soundtrack, Theme, Musical MP3 version RAR size: 1692 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1570 mb WMA version RAR size: 1324 mb Rating: 4.8 Votes: 145 Other Formats: WAV AU MMF VQF APE AIFF VOC Tracklist Timeless Classics –Mary Moder, Dorothy Who's Afraid Of The Big, Bad Wolf (From "Three 1-1 Compton, Pinto Colvig & Billy 3:06 Little Pigs") Bletcher Whistle While You Work (From "Snow White 1-2 –Adriana Caselotti 3:24 And The Seven Dwarfs") 1-3 –Cliff Edwards When You Wish Upon A Star (From "Pinocchio") 3:13 –Cliff Edwards, Jim 1-4 Carmichael & The Hall When I See An Elephant Fly (From "Dumbo") 1:48 Johnson Choir* 1-5 –Disney Studio Chorus* Little April Shower (From "Bambi") 3:53 –Joaquin Garay, José Olivier & 1-6 Three Caballeros (From "The Three Caballeros") 2:09 Clarence Nash 1-7 –James Baskett Zip-A-Dee-Doo-Dah (From "Song Of The South") 2:18 Lavender Blue (Dilly Dilly) (From "So Dear To 1-8 –Burl Ives 1:02 My Heart") A Dream Is A Wish Your Heart Makes (From 1-9 –Ilene Woods 4:35 "Cinderella") –Disney Studio Chorus* & All In The Golden Afternoon (From "Alice In 1-10 2:41 Kathryn Beaumont Wonderland") –Kathryn Beaumont, Bobby You Can Fly! You Can Fly! You Can Fly! (From 1-11 Driscoll, Paul Collins , Tommy 4:23 "Peter Pan") Luske & Jud Conlon Chorus* What A Dog / He's A Tramp (From "Lady And 1-12 –Peggy Lee 2:25 The Tramp") 1-13 –Mary Costa & Bill Shirley Once Upon A Dream (From "Sleeping -

Fitment Chart (Pdf)

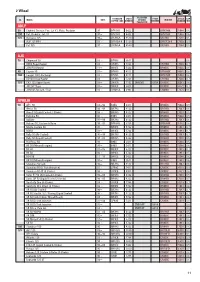

2 Wheel PLATINUM CC MODEL DATE STANDARD STOCK OR GOLD STOCK IRIDIUM STOCK GAP COPPER CORE NUMBER PALLADIUM NUMBER NUMBER MM ADLY 50 Citybird, Crosser, Fox, Jet X1, Pista, Predator 97 BPR7HS 6422 BPR7HIX 5944 0.6 100 Cat, Predator, Jet, X1 97 BPR7HS 6422 BPR7HIX 5944 0.6 125 Activator 125 99 CR7HSA 4549 CR7HIX 7544 0.5 AJP 125 PR4 03 DPR7EA-9 5129 DPR7EIX-9 7803 0.9 Cat 125 97 CR7HSA 4549 CR7HIX 7544 0.5 AJS 50 Chipmunk 50 03 BP4HS 3611 0.6 DD50 Regal Raptor 03 CR7HS 7223 CR7HIX 7544 0.7 JSM 50 Motard 11 BR8ES 5422 BR8EIX 5044 0.6 80 Coyote 80 03 BP6HS 4511 BPR6HIX 4085 0.6 100 Cougar 100 (Jincheng) 03 BP7HS 5111 BPR7HIX 5944 0.6 DD100 Regal Raptor 03 CR7HS 7223 CR7HIX 7544 0.7 125 CR3-125 Super Sports 08 DR8EA 7162 DR8EVX 6354 DR8EIX 6681 0.6 JS125Y Tiger 03 DR8ES 5423 DR9EIX 4772 0.7 JSM125 Motard / Trail 10 CR6HSA 2983 CR6HIX 7274 0.6 APRILIA 50 AF1 50 8892 B8ES 2411 BR8EIX 5044 0.5 Amico 50 9294 BR7HS 4122 BR7HIX 7067 0.6 Area 51 (Liquid Cooled 2-Stroke) 98 BR8HS 4322 BR8HIX 7001 0.5 Extrema 50 93 B8ES 2411 BR8EIX 5044 0.5 Gulliver 9799 BR7HS 4122 BR7HIX 7067 0.6 Habana 50, Custom & Retro 9905 BPR8HS 3725 BPR8HIX 6742 0.6 Mojito Custom 50 05 BR9ES 5722 BR9EIX 3981 0.7 MX50 03 BR9ES 5722 BR9EIX 3981 0.7 Rally 50 (Air Cooled) 9599 BR7HS 4122 BR7HIX 7067 0.7 Rally 50 (Liquid Cooled) 9703 BR8HS 4322 BR8HIX 7001 0.5 Red Rose 50 93 B8ES 2411 BR8EIX 5044 0.5 RS 50 (Minarelli engine) 93 B8ES 2411 BR8EIX 5044 0.6 RS 50 0105 BR9ES 5722 BR9EIX 3981 0.7 RS 50 06 BR9ES 5722 BR9EIX 3981 0.5 RS4 50 1113 BR8ES 5422 BR8EIX 5044 0.6 ‡ Early Ducati Testastretta bikes (749, 998, 999 models) can have very little clearance between the plug hex and the RX 50 (Minarelli engine) 97 B9ES 2611 BR9EIX 3981 0.6 cylinder head that may require a thin walled socket, no larger than 20.5mm OD to allow the plug to be fitted. -

Film Is GREAT, Edition 2, November 2016

©Blenheim Palace ©Blenheim Brought to you by A guide for international media The filming of James Bond’s Spectre, Blenheim Palace, Oxfordshire visitbritain.com/media Contents Film is GREAT …………………………………………………………........................................................................ 2 FILMED IN BRITAIN - British film through the decades ……………………………………………………………………………………….. 9 - Around the world in British film locations ……………………………………………….…………………........ 15 - Triple-take: Britain's busiest film locations …………………………………………………………………….... 18 - Places so beautiful you'd think they were CGI ……………………………………………………………….... 21 - Eight of the best: costume dramas shot in Britain ……………………………………………………….... 24 - Stay in a film set ……………………………………………………………………………………………………………...... 27 - Bollywood Britain …………………………………………………………………………………………………………….... 30 - King Arthur's Britain: locations of legend ……………………………………………………………………...... 33 - A galaxy far, far away: Star Wars in Britain .…………………………………………………………………..... 37 ICONIC BRITISH CHARACTERS - Be James Bond for the day …………………………………………………………………………………………….... 39 - Live the Bridget Jones lifestyle ……………………………………………………………………………………..... 42 - Reign like King Arthur (or be one of his knights) ………………………………………………………….... 44 - A muggles' guide to Harry Potter's Britain ……………………………………………………………………... 46 FAMILY-FRIENDLY - Eight of the best: family films shot in Britain ………………………………………………………………….. 48 - Family film and TV experiences …………………….………………………………………………………………….. 51 WATCHING FILM IN BRITAIN - Ten of the best: quirky -

March 11-20, 2016

The First Act “High Ho” & “Small World” (Snow White “I Can Go the Distance” (Hercules) Lori Zimmermann of State Farm, Chuck Eckberg of RE/MAX Results, and and the Seven Dwarfs) Hercules, Captain Li Shang “When You Wish Upon a Star” (Pinocchio) Seven Dwarfs, Small Youth Chorus “Trashin’ the Camp” & “Two Worlds Jiminy Cricket, Tinker Bell, All Cast Ending” (Tarzan) “Belle (Bon Jour)” (Beauty & the Beast) DISNEY LEADING LADIES Stomp Guys Belle, Aristocratic Lady, Fishman/Eggman, “Bibidy Bobbidy Boo” (Cinderella) “I’ve Been Dreaming of a True Love’s Kiss” PRESENT Sausage Curi Girl, Baker, Hat Seller, Fairy Godmother, Cinderella, Girls (Enchanted) Shepherd Boy, Lady with Cane, Gaston, Chorus II, “Parents”, Little Brothers, Disney Prince Edward LeFou, Silly Girl1, Silly Girl2, Silly Girl3, Photographers Children, Villagers “Some Day My Prince Will Come” (Snow VILLAINS “Topsy Turvy Day” (Hunchback of Notre White and the Seven Dwarfs) “I’ve Got a Dream” (Tangled) Dame) Snow White Hook Hand Thug, Big Nose Thug, Flynn, Clopin (Jester), Esmerelda, Quasimodo, “So This Is Love” (Cinderella) Rapunzel, Thug Chorus Guards, Villagers Cinderella, Prince Charming “Gaston” (Beauty & the Beast) “One Jump Ahead” (Aladdin) “Once Upon a Dream” (Sleeping Beauty) Gaston, Lefou, Silly Girls, Villagers Aladdin, Soloist, Jasmine, Abu, Villagers, Princess Aurora “Step Sisters Lament” (Cinderella) Group of Ladies “Part of Your World” (Little Mermaid) Portia & Joy “For the First Time in Forever” (Frozen) Ariel “Poor Unfortunate Soul” (Little Mermaid) Anna, Castle Folks -

The Green Sheet and Opposition to American Motion Picture Classification in the 1960S

The Green Sheet and Opposition to American Motion Picture Classification in the 1960s By Zachary Saltz University of Kansas, Copyright 2011 Submitted to the graduate degree program in Film and Media Studies and the Graduate Faculty of the University of Kansas in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts. ________________________________ Chairperson Dr. John Tibbetts ________________________________ Dr. Michael Baskett ________________________________ Dr. Chuck Berg Date Defended: 19 April 2011 ii The Thesis Committee for Zachary Saltz certifies that this is the approved version of the following thesis: The Green Sheet and Opposition to American Motion Picture Classification in the 1960s ________________________________ Chairperson Dr. John Tibbetts Date approved: 19 April 2011 iii ABSTRACT The Green Sheet was a bulletin created by the Film Estimate Board of National Organizations, and featured the composite movie ratings of its ten member organizations, largely Protestant and represented by women. Between 1933 and 1969, the Green Sheet was offered as a service to civic, educational, and religious centers informing patrons which motion pictures contained potentially offensive and prurient content for younger viewers and families. When the Motion Picture Association of America began underwriting its costs of publication, the Green Sheet was used as a bartering device by the film industry to root out municipal censorship boards and legislative bills mandating state classification measures. The Green Sheet underscored tensions between film industry executives such as Eric Johnston and Jack Valenti, movie theater owners, politicians, and patrons demanding more integrity in monitoring changing film content in the rapidly progressive era of the 1960s. Using a system of symbolic advisory ratings, the Green Sheet set an early precedent for the age-based types of ratings the motion picture industry would adopt in its own rating system of 1968. -

Enjoy the Magic of Walt Disney World All Year Long with Celebrations Magazine! Receive 6 Issues for $29.99* (Save More Than 15% Off the Cover Price!) *U.S

Enjoy the magic of Walt Disney World all year long with Celebrations magazine! Receive 6 issues for $29.99* (save more than 15% off the cover price!) *U.S. residents only. To order outside the United States, please visit www.celebrationspress.com. To subscribe to Celebrations magazine, clip or copy the coupon below. Send check or money order for $29.99 to: YES! Celebrations Press Please send me 6 issues of PO Box 584 Celebrations magazine Uwchland, PA 19480 Name Confirmation email address Address City State Zip You can also subscribe online at www.celebrationspress.com. Cover Photography © Mike Billick Issue 44 The Rustic Majesty of the Wilderness Lodge 42 Contents Calendar of Events ............................................................ 8 Disney News ...........................................................................10 MOUSE VIEWS ......................................................... 15 Guide to the Magic by Tim Foster............................................................................16 Darling Daughters: Hidden Mickeys by Steve Barrett ......................................................................18 Diane & Sharon Disney 52 Shutters & Lenses by Tim Devine .........................................................................20 Disney Legends by Jamie Hecker ....................................................................24 Disney Cuisine by Allison Jones ......................................................................26 Disney Touring Tips by Carrie Hurst .......................................................................28 -

A Critical Reading of Age and Aging in Snow White and the Huntsman and Mirror Mirror

Of Young/Old Queens and Giant Dwarfs: A Critical Reading of Age and Aging in Snow White and the Huntsman and Mirror Mirror Anita Wohlmann This article1 draws on the curious coincidence of several film releases of the “Snow White” tale in 2012. The Internet Movie Database lists five films with direct references to the fairy tale, among them Snow White and the Huntsman (directed by Rupert Sanders, starring Charlize Theron and Kristen Stewart) and Mirror Mirror (directed by Tarsem Singh, starring Julia Roberts and Lily Collins).2 According to Jack Zipes, who collected thirty-five cinematographic representations of “Snow White” in The Enchanted Screen (2011), there is a “profound widespread public inter- est in a tale [i.e., “Snow White”] that provokes retelling and reflection because it touches upon deeply rooted problems in every culture of the world ranging from what constitutes our notions of beauty to what causes conflicts between women, especially mothers and daughters and stepmothers and daughters” (119). Which “deeply rooted problem” has inspired this recent revival of “Snow White”? Why do we keep retelling this particular fairy tale?3 Maria Tatar suggests that it is the topic of aging that preoccupies contemporary directors, screenwriters, and audiences: “It may be that there is something about the boomer anxiety about aging that is renewing our interest in Snow White” (Ulaby). In The New Yorker, she adds that Snow White and the Huntsman “captures a deepening anxiety about aging and generational sexual rivalry” (Tatar). The rivalry between mothers and daughters has been a central issue in Second Wave feminist criticism (see, e.g., Barzilai; Gilbert and Gubar). -

The Moon in the Mango Tree Pamela Binnings Ewen

The Moon in the Mango Tree Pamela Binnings Ewen 1 To Barbara Jeanne Perkins Binnings and June Perkins Anderson Z Z Z And in memory of Muriel Carol Austgen 3 Perhaps her faults and follies, the unhappiness she had suffered, were not entirely vain if she could follow the path that she now dimly discerned before her . the path that led to peace. W. Somerset Maugham The Painted Veil 4 Prologue At the mouth of the Menam—the Chao Phraya River—fireflies covering mangrove bushes at the edge of the water sparkled in strange unison through the dusk, creating beacons of light that were seen for miles. The river flows to the Gulf of Siam from Bangkok. It is the key that unlocks the mysteries of Siam to weary travelers arriving by sea. As Harvey and I peered from the deck of the Empress of Asia, we saw each bush glimmer with light from the fireflies then quickly disappear into the gloaming—on and off together as if they were one, light, then dark. Siam, as I knew it then, has disappeared as the light of those fireflies. Today it is known as Thailand, the land of the free people. It smolders beneath the white-hot glare of the sun, just a few degrees south of the Tropic of Cancer. When we arrived at the end of the year 1919, Siam was laughter, music, color. Many years later I fled the country and the rage of darkness that howled within me. This is our story, my child—Harvey’s and mine.