Heroic and Holy Holiness As We Understand I

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Certified School List 4-13-2016.Xlsx

Updated SEVP Certified Schools April 13, 2016 SCHOOL NAME CAMPUS NAME F M CITY ST CAMPUS ID "I Am" School Inc. "I Am" School Inc. Y N Mount Shasta CA 41789 424 Aviation 424 Aviation N Y Miami FL 103705 ‐ A ‐ A F International School of Languages Inc. A F International of Westlake Y N Westlake Village CA 57589 Village A F International School of Languages Inc. A F International College Y N Los Angeles CA 9538 A. T. Still University of Health Sciences Kirksville Coll of Osteopathic Y N Kirksville MO 3606 Medicine Aaron School Aaron School ‐ 30th Street Y N New York NY 159091 Aaron School Aaron School Y N New York NY 114558 ABC Beauty Academy, INC. ABC Beauty Academy, INC. N Y Flushing NY 95879 ABC Beauty Academy, LLC ABC Beauty Academy N Y Garland TX 50677 Abcott Institute Abcott Institute N Y Southfield MI 197890 Aberdeen School District 6‐1 Aberdeen Central High School Y N Aberdeen SD 36568 Abiding Savior Lutheran School Abiding Savior Lutheran School Y N Lake Forest CA 9920 Abilene Christian Schools Abilene Christian Schools Y N Abilene TX 8973 Abilene Christian University Abilene Christian University Y N Abilene TX 7498 Abington Friends School Abington Friends School Y N Jenkintown PA 20191 Abraham Baldwin Agricultural College Tifton Campus Y N Tifton GA 6931 Abraham Joshua Heschel School Abraham Joshua Heschel School Y N New York NY 106824 ABT Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis School ABT Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis Y Y New York NY 52401 School Abundant Life Christian School Abundant Life Christian School Y N Madison WI 24403 ABX Air, Inc. -

Celebrating 500 Years of the Gift of Faith Filipinos Hold Sinulog Festival (Page 35)

PUBLICATION OF THE CATHOLIC DIOCESE OF CHRISTCHURCH Issue 126 - Lent 2021 CELEBRATING 500 YEARS OF THE GIFT OF FAITH FILIPINOS HOLD SINULOG FESTIVAL (page 35) The fluvial procession at the Avon with the statue of the Sto. Niño at the head of the boats. CELEBRATING OUR NEWLY EMERGING PARISHES (page 10) COLLEGE STUDENT LEADERSHIP (page 20) RECALLING COVERAGE OF CANTERBURY EARTHQUAKES (page 24) GATHERING AT FOURVIÈRE (page 32) From Our Archbishop Greetings to you as we enter this Holy Week. Our time of Lenten preparation is coming to a conclusion and we are about to celebrate the death and resurrection of Our Lord Jesus Christ. I do hope that this Lenten time has given you the opportunity to prepare your hearts and minds well for this most central of celebrations for us as Christian people. For when we truly create the time and space to reflect and pray the Holy Spirit and the grace of God can work most powerfully in us. Trusting in God familiar to us in our existing parishes. Yet amid all of this change, we have This was both a time of sadness and faith and trust that God is at work. 2020 was a challenging year for also hope for the future. We have We try to be attuned to what God is so many of us. We went through watched the Cathedral of the Blessed asking of us, try to read the signs of the Covid-19 lockdown with all Sacrament being deconstructed the time, try to see what is of God and its ramifications. -

Northeast Is a Bimonthly Publication for Sisters of Mercy, Companions in Mercy and Mercy Associates of the Northeast Northeast Community

MERCY VOLUME 5 I Number 6 Mercy Northeast is a bimonthly publication for Sisters of Mercy, Companions in Mercy and Mercy Associates of the Northeast Northeast Community. Send comments to: The Institute of the Sisters of Mercy of the Americas [email protected]. Albany I Connecticut I New Hampshire I Portland I Providence I Vermont Catherine’s Facebook friends number 3,100+ Facebook is a phenomenon. This internet tool is credited with more than 300 million active users. Today, social networking sites like Facebook and Twitter are invaluable forms of communication – it’s fast, it’s easy, it’s free and the audience is huge. About a year ago, Northeast Community Mercy Associate Erin Saiz Hanna created a Facebook page for Catherine McAuley. It was done on a whim to entice her friend, Sister Marianna Sylvester, to join Facebook. The Mercy Associate morning after Catherine’s page went live, however, Erin was shocked to Erin Saiz Hanna find Catherine had 200 Facebook friend requests from around the world. To date, Catherine’s Facebook friends number over 3,100, and this number Facebook Statistics continues to grow daily. (Marianna joined many months later.) • Average users have 130 Erin spends approximately 15-30 minutes each day maintaining the site – friends on the site accepting friend requests, answering messages, posting ways to get involved • The fastest growing with Mercy ministries, and sharing Mercy news coverage received through demographic is individuals Google RSS feeds. Catherine belongs to 66 group pages and is a fan of 22 who are 35 years old and older pages, all of which are directly connected to Mercy ministries or schools. -

Certified School List 03-26-2015.Xlsx

Updated SEVP Certified Schools March 26, 2015 SCHOOL NAME CAMPUS NAME F M CITY ST CAMPUS ID "I Am" School Inc. "I Am" School Inc. Y N Mount Shasta CA 41789 424 Aviation 424 Aviation N Y Miami FL 103705 ‐ A ‐ A F International School of Languages Inc. A F International College Y N Los Angeles CA 9538 A F International School of Languages Inc. A F International of Westlake Y N Westlake Village CA 57589 Village A. T. Still University of Health Sciences Kirksville Coll of Osteopathic Y N Kirksville MO 3606 Medicine Aaron School Aaron School ‐ 30th Street Y N New York NY 159091 Aaron School Aaron School Y N New York NY 114558 ABC Beauty Academy, INC. ABC Beauty Academy, INC. N Y Flushing NY 95879 ABC Beauty Academy, LLC ABC Beauty Academy N Y Garland TX 50677 Abcott Institute Abcott Institute N Y Southfield MI 197890 Aberdeen Catholic School System Roncalli Y N Aberdeen SD 21405 Aberdeen Catholic School System Roncalli Primary Y N Aberdeen SD 180510 Aberdeen Catholic School System Roncalli Elementary Y N Aberdeen SD 180511 Aberdeen School District 6‐1 Aberdeen Central High School Y N Aberdeen SD 36568 Abiding Savior Lutheran School Abiding Savior Lutheran School Y N Lake Forest CA 9920 Abilene Christian Schools Abilene Christian Schools Y N Abilene TX 8973 Abilene Christian University Abilene Christian University Y N Abilene TX 7498 Abington Friends School Abington Friends School Y N Jenkintown PA 20191 Above It All, Inc Benchmark Flight /Hawaii Flight N Y Kailua‐Kona HI 24353 Academy Abraham Baldwin Agricultural College Tifton Campus Y N Tifton GA 6931 Abraham Joshua Heschel School Abraham Joshua Heschel School Y N New York NY 106824 ABT Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis School ABT Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis Y Y New York NY 52401 School Abundant Life Academy Abundant Life Academy‐Virginia Y N Milford VA 81523 Abundant Life Christian School Abundant Life Christian School Y N Madison WI 24403 ABX Air, Inc. -

Early Nineteenth-Century Women Interpret Scripture in New Ways for New Times

Reading with our Foresisters: Aguilar, King, McAuley and Schimmelpenninck— Early Nineteenth-Century Women Interpret Scripture in New Ways for New Times by Elizabeth Mary Davis A Thesis submitted to the Faculty of Regis College and the Graduate Centre for Theological Studies of the Toronto School of Theology. In partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Theology awarded by Regis College and the University of Toronto. © Copyright by Elizabeth Mary Davis 2019 Reading with our Foresisters: Aguilar, King, McAuley and Schimmelpenninck— Early Nineteenth-Century Women Interpret Scripture in New Ways for New Times Elizabeth Mary Davis Doctor of Theology Regis College and The University of Toronto 2019 Abstract Biblical hermeneutics today is marked by increased attention to women’s experience and voices in interpretation, the illustration of alternatives to the historical-critical approach to create a plurality of interpretation as the interpretive norm, exploration of the social location of earlier interpreters, determination of authority for biblical interpretation, and expansion of hermeneutics to include praxis (a manifestation of embodied or lived theology). This thesis shows that these elements are not completely new, but they are actually embedded in scriptural interpretation from two hundred years ago. The exploration of the biblical interpretation of four women—Grace Aguilar, Frances Elizabeth King, Catherine McAuley and Mary Anne Schimmelpenninck—who lived at the same time in the early nineteenth century in the same geographic region and who represent the spectrum of readers of the Bible, concludes that the interpretive works of these four women were prototypical of and anticipated these elements. ii To guide this exploration, the thesis appropriates the construct of the hermeneutic triangle, examining the social location of the four women, their texts about the Bible and the hermeneutic by which they interpreted the biblical texts. -

Tablet Features Spread

175 YEARS – 50 GREAT CATHOLICS / Carmen Mangion on Sr Mary Clare Moore Born in Dublin To mark our anniversary, we have invited 50 Catholics to choose adored. In October 1854 she led on 20 March a person from the past 175 years whose life has been a personal a party of four Bermondsey sisters 1814, Georgiana inspiration to them and an example of their faith at its best to join Nightingale to nurse in the Moore converted Crimea. Jerry Barrett’s painting to Catholicism the first four women to join her, the leaders that founded nine Mission of Mercy: Florence with her mother taking the name Mary Clare. Convents of Mercy in England. Nightingale receiving the wounded in 1823. Aged Aged 23, Moore became supe- She worked well with the at Scutari (in the National Portrait 14, she was rior of the Cork convent. Then in English hierarchy, becoming a Gallery) gives us our only contem- employed by the founder of the 1839, she was lent to the first close and trusted confidante of porary image of her. Her face, like Sisters of Mercy, Catherine English foundation in the slums Thomas Grant, the Bishop of her life, is in the shadows. McAuley, as a governess but was of Bermondsey, south London. Southwark. Her letters to her sis- Mary Clare Moore died of soon drawn by her House of She managed the Convent of ters reflect her compassion and pleurisy in 1874, aged only 60, Mercy, a refuge and school for Mercy in Bermondsey until her encouragement. She wrote to con- but worn out by her exertions on impoverished female servants death in 1874. -

Sisters Say Farewell to Sister Angele

S P O N S O R E D INSTITUTIONS Catherine McAuley Center West Midwest Update Mount Mercy College Mercy Medical Center Sisters, associates, employees of Sacred Heart Convent and sponsored works, and committee members from the Cedar Rapids Regional Community had CO - SPONSOR a chance to meet the first employees of the Sisters of Mercy West Midwest Community. Mercy Housing, Inc. LEADERSHIP TEAM In their first weeks on the job, the West Midwest Community Operating 2003 - 2008 Officer (COO), Kim Kinsel and Community Financial Officer (CFO), Kathy Thornton, RSM, President Carol Kelley visited Sacred Heart Convent, December 5 – 6. During their visit, the women were able to learn about the Cedar Rapids Regional Shari Sutherland, RSM, Vice President Community’s ministries and operations. In addition to learning about the Margaret Weigel, RSM, Councilor Cedar Rapids Regional Community’s culture, the women were also able to visit the other five regional communities in Auburn and Burlingame, ADMINISTRATIVE California; Chicago; Detroit and Omaha that will comprise the West S TA F F Midwest Community. The women have been meeting with committees Theresa Baldus-Kokontis, and will make a presentation to the West Midwest Community Leadership Administrator Teams regarding budgets and administrative structure. Jessica Folkerts, Administrative Assistant Jenny Johnson, Business Manager The West Midwest Community will become official on July 1. The Melissa Looney, Director of Development COO and CFO will report to the leadership team for the West Midwest and Communications Community which will be elected during the West Midwest 2008 Inaugural Assembly, March 24 – 30 in Chicago. Direct address changes to: The formation of the West Midwest Community is part of the reorganization across the Institute of the Sisters of Mercy of the Americas Mercy Works to more effectively combine resources and create a streamlined, efficient Sisters of Mercy Cedar Rapids Regional Community governing structure. -

News from Mother Mcauley High School This Is a Publication of St

inscapeWINTER 2014 News from Mother McAuley High School This is a publication of St. Xavier Academy/ Mother McAuley Liberal Arts High School. our mission MOTHER McAULEY LIBERAL ARTS HIGH SCHOOL is a Catholic educational community committed to providing a quality secondary education for young women. In the tradition of the Sisters of Mercy and their foundress, Catherine McAuley, we prepare students to live in a complex, dynamic society by teaching them to think critically, communicate effectively, respond compassionately to the needs of their community and assume roles of Christian leadership. In partnership with parents, we empower young women to acknowledge their giftedness and to make decisions with a well-developed moral conscience. We foster an appreciation of the diversity of the global community and a quest for knowledge and excellence as lifelong goals. PRESIDENT Mary Acker Klingenberger ‘75 PRINCIPAL Claudia Woodruff For nearly 170 years, Mother McAuley High School, preceded by Saint Xavier Academy has provided to young women of Chicagoland, a quality Catholic education seeped in the Mercy tradition. This would not be possible without the generous support of the Sisters of OFFICE OF INSTITUTIONAL ADVANCEMENT Mercy, alumnae, donors, the community, and our many volunteers. This year we’ve coupled this table of contents VICE PRESIDENT OF INSTITUTIONAL annual report with Inscape, our alumnae magazine, as we believe it’s the best way to share with you examples of how your gifts have helped to prepare our students for college, careers and Letters 3-5 ADVANCEMENT Carey Temple Harrington ’86 leadership roles in our community. Funding our Future 6-9 ALUMNAE COORDINATOR Gift of Giving 10 This past year, the areas of focus for the Board of Trustees included stabilizing enrollment, Linda Balchunas Jandacek ‘84 ensuring financial stability, and welcoming our new president, Mary Acker Klingenberger ’75, Paying it Forward 11 our first alumna president. -

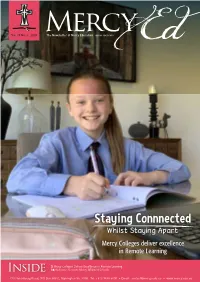

5792 Mercy Ed March Sept 2020 V3.Indd

Mercy Vol. 25 No. 2 2020 The Newsletter of Mercy Education ABN 69 154 531 870 Ed Staying Connnected Whilst Staying Apart Mercy Colleges deliver excellence in Remote Learning 2 Mercy Colleges Deliver Excellence in Remote Learning Inside 16 Welcome to more Mercy Affiliated Schools 720 Heidelberg Road, (PO Box 5067), Alphington Vic 3078 Tel: +613 9490 6600 • Email: [email protected] • www.mercy.edu.au Mercy Co deliver e in R Editorial 2020 has and continues to present challenges for our Mercy school In unprecedented and challenging times, communities and it is in this edition of the Mercy Ed that we wish to acknowledge the hardships and successes during these current Mercy schools have exceled in continuing to and unusual times. Across all our communities, these challenges have been met head-on with innovation, positiveness, resilience deliver excellence in education in a remote and concern for each and every member. Despite the different environment. While challenges were presented degrees of disruption and lockdown caused by COVID-19 across the States, every community has been impacted in some way or to different degrees in the different States, another with reduced travel, fewer excursions and changes in school and family life. each college was able to design, develop Our Year 12 students face their final year of schooling with different and customise learning platforms. Wellbeing levels of personal contact and socialising than they normally would. As always it will be a special year for them to remember and one programs were introduced to keep students in which they will have tried their very best to achieve their goals and fulfil their dreams. -

December 15, 2019

December 15, 2019 “As Disciples of Jesus Christ, we are a giving, growing Catholic family. Through the intercession of Mary, we worship, we pray, we study, we serve and we witness in Faith.” OUR LADY OF VICTORY PAGE 2 NORTHVILLE, MICHIGAN Around the Table Rev. Denis B. Theroux, Pastor Third Sunday of Advent Dear Friends, Today, the third Sunday of Advent is called ‘Gaudete Sunday’ which means ‘Joy’ or Rejoice’. The opening antiphon for today’s liturgy asks us to Rejoice is the Lord always; again, I say rejoice. Indeed, the Lord is near. Today, on our Advent Wreath we light our pink candle to mark this day of joy. St. Paul’s advice and encouragement from the first reading today gives this third Sunday of Advent its traditional name Gaudete Sunday. Joy is the central message of our readings and prayers this Sunday, and indeed the whole of Advent and the celebration of Jesus. One of the most well-known Christmas carols is ‘Joy to world.’ The words to this carol were written by Isaac Watts in 1719. At Christmas it will be sung all over the world. The music for it comes from Handel’s ‘Messiah.’ The first words that Mary hears when she is told that she is going to be the mother of Jesus are, ‘Rejoice, so highly favored.’ Mary is to be filled with joy because God has called her by her name and her son will be the long-awaited Messiah. When she goes to see Elizabeth her cousin, she breaks into song, singing out loudly, ‘My souls proclaims the greatness of the Lord, my spirit rejoices in God my savior’. -

Archdiocesan Archives, Sydney

297 BIBLIOGRAPHY A. Archives and Other Repositories Australia (i) Archives Office of New South Wales (ii) Archdiocesan Archives, Sydney (iii) Brigidine Sisters, Maroubra (iv) Sisters of the Good Samaritan, Sydney (v) Sisters of St Joseph, North Sydney (vi) Sisters of St Joseph, Lochinvar (vii) Sisters of Mercy, Singleton (viii) Sisters of St Dominic, Strathfield (ix) Maitland Diocesan Archive,, Newcastle (x) Parish Registers: (a) Taree (b) West Maitland (c) East Maitland (d) Newcastle (e) Singleton (xi) Newcastle Region Library Ireland (i) All Hallows, Dublin (ii) Maynooth College, Maynoo th (iii) Clare Heritage Centre, Corcfin, Co. Clare (iv) Archdiocesan Archives, Dublin (v) National Archives, Dublin (vi) National Library, Dublin (vi) Registry of Deeds, Dublin (vii) Valuation Office, Dublin (viii) Wicklow Heritage Centre, Co. Wicklow Italy (Rome) (i) Sacred Congregation for the Evangelization of Peoples ii) Irish College (iii) University of Propaganda ride B. Contemporary Works (i) Books (ii) Almanacs and Directories (iii) Proceedings, Constitutions and Rules. (iv) Jubilee Publications (v) Encyclopaedias and other compilations (vi) Newspapers C. Secondary Sources (i) Books (ii) Articles (iii) Theses (iv) Other 298 A. ARCHIVES AND OTHER REPOSITORIES AUSTRALIA Archives Office of New South Wales Assisted Immigrants Shipping A rriving Sydney and Newcastle. (Board's Lists); 1856-1859, Reel 2137 to Reel 24791860-1879 and 2480 to Reel 2490 Commissioner of Stamp Duties New South Wales Immigration Agent to Police Magistrate, Maitland, 13 April -

Celebrating Years

inscape News from Mother McAuley High School FALL 2016 Celebrating YEARS table of contents n Returning to Catherine’s Roots 4 n Fitzgerald Sisters 9 n Reunions 13 n Alumnae News & Events 14 n Advancement Updates 25 Carey Temple Harrington ‘86 Vice President of Institutional Advancement n School News 26 Jennifer Ligda Busk ‘93 Director of Marketing & Communications n Jubilarians 34 JoAnn Foertsch Altenbach ‘76 n Giving Opportunities 35 Annual Fund Coordinator Kathleen Kelly ‘09 Marketing & Communications Assistant Find Us Online Mother McAuley Liberal Arts High School (formerly Saint Xavier Academy) @McAuleyMacs Inscape Magazine is published twice a year by Mother McAuley Liberal Arts High School. @mothermcauley POSTMASTER: Send address changes to Alumnae Relations, Mother McAuley High School, 3737 W. 99th Street, Mother McAuley Liberal Arts Chicago, IL 60655. High School Alumnae Copyright 2016 Mother McAuley Liberal Arts High School. Reproduction in whole or part is prohibited without written permission. www.mothermcauleyalums.org www.mothermcauley.org Design and layout by Karen Culloden Hoey ‘84 Printing by Accurate Printing President’s Letter It was 60 years this fall that the doors to Mother McAuley Liberal Arts High School opened. This milestone was the result of the vision of the Sisters of Mercy who foresaw how the educational landscape for young women would continue to evolve from our early days as the first girls’ Catholic school -- Saint Xavier Academy – located on Prairie Ave. Although uncertain of the ways of the world, the Sisters of Mercy arrived in Chicago in 1846. Pioneers and leaders in the face of great adversity, they were determined in the work they set out to accomplish, and quickly established Mercy Hospital and Saint Xavier Academy and College.