Toward a Kripkean Concept of Number

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Justin Clarke-Doane Department of Philosophy Columbia University 708 Philosophy Hall, MC: 4971 1150 Amsterdam Avenue New York, New York 10027 [email protected]

Justin Clarke-Doane Department of Philosophy Columbia University 708 Philosophy Hall, MC: 4971 1150 Amsterdam Avenue New York, New York 10027 [email protected] Primary Appointment 2021 – Present Associate Professor with tenure, Columbia University, USA Other Appointments 2014 – Present Honorary Research Fellow, University of Birmingham, UK 2013 – Present Adjunct Research Associate, Monash University, Australia Visiting Appointments June 2015 Visiting Professor, Renmin University of China (RUC) October 2012 Visiting Scholar, Institute for the History and Philosophy of Science and Technology (IHPST), Université Paris 1 Panthéon-Sorbonne Previous Appointments 2019 – 2021 Associate Professor, Columbia University, USA 2014 – 2019 Assistant Professor, Columbia University, USA 2013 – 2014 Birmingham Research Fellow (permanent), University of Birmingham 2011 – 2013 Lecturer (fixed-term), Monash University Education 2005 – 2011 Ph.D. Philosophy, New York University (NYU) Dissertation: Morality and Mathematics Committee: Hartry Field (Advisor), Thomas Nagel, Derek Parfit, Stephen Schiffer 1 2001 – 2005 B.A., Philosophy/Mathematics, New College of Florida (the honors college of the state university system of Florida) Thesis: Attribute-Identification in Mathematics Committee: Aron Edidin (Advisor), Karsten Henckell, Douglas Langston Areas of Research Metaethics, Metaphysics, Epistemology, Philosophy of Logic & Mathematics Areas of Competence Normative & Applied Ethics, Philosophy of Mind, Philosophy of Physics, Logic & Set Theory Honors and Awards 2020 Morality and Mathematics chosen for symposia at Philosophy and Phenomenological Research and Analysis. 2019 Lavine Scholar 2017 Chamberlain Fellowship 2015 “Moral Epistemology: The Mathematics Analogy” selected by Philosopher’s Annual as one of the “tenbest articles published in philosophy in 2014”. 2015 “Moral Epistemology: The Mathematics Analogy” selected as a “Notable Writing” in The Best Writing on Mathematics 2015. -

Pointers to Truth Author(S): Haim Gaifman Reviewed Work(S): Source: the Journal of Philosophy, Vol

Journal of Philosophy, Inc. Pointers to Truth Author(s): Haim Gaifman Reviewed work(s): Source: The Journal of Philosophy, Vol. 89, No. 5 (May, 1992), pp. 223-261 Published by: Journal of Philosophy, Inc. Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/2027167 . Accessed: 09/01/2012 10:03 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Journal of Philosophy, Inc. is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to The Journal of Philosophy. http://www.jstor.org +- * -+ THE JOURNAL OF PHILOSOPHY VOLUME LXXXIX, NO. 5, MAY 1992 POINTERS TO TRUTH* C onsider the following: Jack: What I am saying at this very moment is nonsense. Jill: Yes, what you have just said is nonsense. Apparently, Jack spoke nonsense and Jill spoke to the point. But Jack and Jill seem to have asserted the same thing: that Jack spoke nonsense. Wherefore the difference? To avoid the vagueness and the conflicting intuitions that go with 'nonsense', let us replace it by 'not true' and recast the puzzle as follows: line 1: The sentence on line 1 is not true. line 2: The sentence on line 1 is not true. -

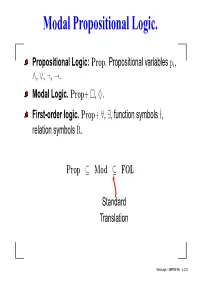

Modal Propositional Logic

Modal Propositional Logic. Propositional Logic: Prop . Propositional variables pi, ∧, ∨, ¬, →. Modal Logic. Prop + , ♦. First-order logic. Prop + ∀, ∃, function symbols f˙, relation symbols R˙ . Prop ⊆ Mod ⊆ FOL Standard Translation Core Logic – 2007/08-1ab – p. 2/30 The standard translation (1). Let P˙i be a unary relation symbol and R˙ a binary relation symbol. We translate Mod into L = {P˙i, R˙ ; i ∈ N}. For a variable x, we define ST x recursively: ST x(p i) := P˙i(x) ST x(¬ϕ) := ¬ST x(ϕ) ST x(ϕ ∨ ψ) := ST x(ϕ) ∨ ST x(ψ) ˙ ST x(♦ϕ) := ∃y R( x, y ) ∧ ST y(ϕ) Core Logic – 2007/08-1ab – p. 3/30 The standard translation (2). If hM, R, V i is a Kripke model, let Pi := V (p i). If Pi is a unary relation on M, let V (p i) := Pi. Theorem. hM, R, V i |= ϕ ↔ h M, P i, R ; i ∈ Ni |= ∀x ST x(ϕ) Corollary. Modal logic satisfies the compactness theorem. Proof. Let Φ be a set of modal sentences such that every finite set has a model. Look at ∗ ∗ Φ := {∀ x ST x(ϕ) ; ϕ ∈ Φ}. By the theorem, every finite subset of Φ has a model. By compactness for first-order logic, Φ∗ has a model. But then Φ has a model. q.e.d. Core Logic – 2007/08-1ab – p. 4/30 Bisimulations. If hM, R, V i and hM ∗, R ∗, V ∗i are Kripke models, then a relation Z ⊆ M × N is a bisimulation if ∗ ∗ If xZx , then x ∈ V (p i) if and only if x ∈ V (p i). -

An Overview of Saharon Shelah's Contributions to Mathematical Logic, in Particular to Model Theory

An overview of Saharon Shelah's contributions to mathematical logic, in particular to model theory∗ Jouko V¨a¨an¨aneny Department of Mathematics and Statistics University of Helsinki Finland March 7, 2020 I will give a brief overview of Saharon Shelah's work in mathematical logic, especially in model theory. It is a formidable task given the sheer volume and broad spectrum of his work, but I will do my best, focusing on just a few main themes. In the statement that Shelah presented for the Schock Prize Committee he wrote: I would like to thank my students, collaborators, contemporary logicians, my teachers Haim Gaifman and Azriel Levy and my advisor Michael Rabin. I have been particularly influenced by Alfred Tarski, Michael Morley and Jerome Keisler. As it happens, in 1971 there was a birthday meeting in Berkeley in honor of Alfred Tarski. All of these people were there and gave talks. Shelah's contribution to the Proceedings Volume of this meeting [5] is number 31 in the numbering of his papers, which now extends already to 1150. The papers are on the internet, often referred to by their \Shelah-number". We ∗This overview is based on a lecture the author gave in the Rolf Schock Prize Sym- posium in Logic and Philosophy in Stockholm, 2018. The author is grateful to Andrew Arana, John Baldwin, Mirna Dzamonja and Juliette Kennedy for comments concerning preliminary versions of this paper. yWhile writing this overview the author was supported by the Fondation Sciences Math´ematiquesde Paris Distinguished Professor Fellowship, the Faculty of Science of the University of Helsinki, and grant 322795 of the Academy of Finland. -

Studia Humana Volume 9:3/4 (2020) Contents Judgments and Truth

Studia Humana Volume 9:3/4 (2020) Contents Judgments and Truth: Essays in Honour of Jan Woleński (Andrew Schumann)……………………… ………………………………………………………....1 Proof vs Truth in Mathematics (Roman Murawski).………………………………………………………..…………………..……10 The Mystery of the Fifth Logical Notion (Alice in the Wonderful Land of Logical Notions) (Jean-Yves Beziau)……………………………………..………………… ………………………..19 Idea of Artificial Intelligence (Kazimierz Trzęsicki)………………………………………………………………………………..37 Conjunctive and Disjunctive Limits: Abstract Logics and Modal Operators (Alexandre Costa-Leite, Edelcio G. de Souza)…………………………..….....................................66 A Judgmental Reconstruction of Some of Professor Woleński’s Logical and Philosophical Writings (Fabien Schang)…………………………………………………………………….…...……….....72 Reism, Concretism and Schopenhauer Diagrams (Jens Lemanski, Michał Dobrzański)……………………………………………………………...104 Deontic Relationship in the Context of Jan Woleński’s Metaethical Naturalism (Tomasz Jarmużek, Mateusz Klonowski, Rafał Palczewski)……………………………...……….120 A Note on Intended and Standard Models (Jerzy Pogonowski)………………………………………………………………………………..131 About Some New Methods of Analytical Philosophy. Formalization, De-formalization and Topological Hermeneutics (Janusz Kaczmarek)………………………………………………………………………………..140 Anti-foundationalist Philosophy of Mathematics and Mathematical Proofs (Stanisław Krajewski)………….…………………………………………………………………. 154 Necessity and Determinism in Robert Grosseteste’s De libero arbitrio (Marcin Trepczyński)……………………….……………………………………………………...165 -

Interstructure Lattices and Types of Peano Arithmetic

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works All Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects 9-2017 Interstructure Lattices and Types of Peano Arithmetic Athar Abdul-Quader The Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/2196 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] Interstructure Lattices and Types of Peano Arithmetic by Athar Abdul-Quader A dissertation submitted to the Graduate Faculty in Mathematics in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, The City University of New York 2017 ii c 2017 Athar Abdul-Quader All Rights Reserved iii This manuscript has been read and accepted by the Graduate Faculty in Mathematics in satisfaction of the dissertation requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Roman Kossak Date Chair of Examining Committee Ara Basmajian Date Executive Officer Roman Kossak Alfred Dolich Russell Miller Philipp Rothmaler Supervisory Committee The City University of New York iv Abstract Interstructure Lattices and Types of Peano Arithmetic by Athar Abdul-Quader Advisor: Professor Roman Kossak The collection of elementary substructures of a model of PA forms a lattice, and is referred to as the substructure lattice of the model. In this thesis, we study substructure and interstructure lattices of models of PA. We apply techniques used in studying these lattices to other problems in the model theory of PA. -

Iterated Ultrapowers for the Masses

Arch. Math. Logic DOI 10.1007/s00153-017-0592-1 Mathematical Logic Iterated ultrapowers for the masses Ali Enayat1 · Matt Kaufmann2 · Zachiri McKenzie1 Received: 19 February 2017 / Accepted: 22 September 2017 © The Author(s) 2017. This article is an open access publication Abstract We present a novel, perspicuous framework for building iterated ultrapow- ers. Furthermore, our framework naturally lends itself to the construction of a certain type of order indiscernibles, here dubbed tight indiscernibles, which are shown to provide smooth proofs of several results in general model theory. Keywords Iterated ultrapower · Tight indiscernible sequence · Automorphism Mathematics Subject Classification Primary 03C20; Secondary 03C50 1 Introduction and preliminaries One of the central results of model theory is the celebrated Ehrenfeucht–Mostowski theorem on the existence of models with indiscernible sequences. All textbooks in model theory, including those of Chang and Keisler [4], Hodges [16], Marker [27], and Poizat [28] demonstrate this theorem using essentially the same compactness argument B Ali Enayat [email protected] Matt Kaufmann [email protected] Zachiri McKenzie [email protected] 1 Department of Philosophy, Linguistics, and Theory of Science, University of Gothenburg, Box 200, 405 30 Gothenburg, Sweden 2 Department of Computer Science, The University of Texas at Austin, 2317 Speedway, Stop D9500, Austin, TX 78712-1757, USA 123 A. Enayat et al. that was originally presented by Ehrenfeucht and Mostowski in their seminal 1956 paper [6], using Ramsey’s partition theorem. The source of inspiration for this paper is a fundamentally different proof of the Ehrenfeucht–Mostowski theorem that was discovered by Gaifman [14] in the mid- 1960s, a proof that relies on the technology of iterated ultrapowers, and in contrast with the usual proof, does not invoke Ramsey’s theorem. -

Proceedings of the Tarski Symposium *

http://dx.doi.org/10.1090/pspum/025 PROCEEDINGS OF THE TARSKI SYMPOSIUM *# <-r ALFRED TARSKI To ALFRED TARSKI with admiration, gratitude, and friendship PROCEEDINGS OF SYMPOSIA IN PURE MATHEMATICS VOLUME XXV PROCEEDINGS of the TARSKI SYMPOSIUM An international symposium held to honor Alfred Tarski on the occasion of his seventieth birthday Edited by LEON HENKIN and JOHN ADDISON C. C. CHANG WILLIAM CRAIG DANA SCOTT ROBERT VAUGHT published for the ASSOCIATION FOR SYMBOLIC LOGIC by the AMERICAN MATHEMATICAL SOCIETY PROVIDENCE, RHODE ISLAND 1974 PROCEEDINGS OF THE TARSKI SYMPOSIUM HELD AT THE UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, BERKELEY JUNE 23-30, 1971 Co-sponsored by The University of California, Berkeley The Association for Symbolic Logic The International Union for History and Philosophy of Science- Division of Logic, Methodology and Philosophy of Science with support from The National Science Foundation (Grant No. GP-28180) Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data nv Tarski Symposium, University of California, Berkeley, 1971. Proceedings. (Proceedings of symposia in pure mathematics, v. 25) An international symposium held to honor Alfred Tarski; co-sponsored by the University of California, Berkeley, the Association for Symbolic Logic [and] the International Union for History and Philosophy of Science-Division of Logic, Methodology, and Philosophy of Science. Bibliography: p. 1. Mathematics-Addresses, essays, lectures. 2. Tarski, Alfred-Bibliography. 3. Logic, Symbolic and mathematical-Addresses, essays, lectures. I. Tarski, Alfred. II. Henkin, Leon, ed. III. California. University. IV. Association for Symbolic Logic. V. International Union of the History and Philosophy of Sci• ence. Division of Logic, Methodology and Philosophy of Science. VI. Series. QA7.T34 1971 51l'.3 74-8666 ISBN 0-8218-1425-7 Copyright © 1974 by the American Mathematical Society Second printing, with additions, 1979 Printed in the United States of America All rights reserved except those granted to the United States Government. -

Perpetual Motion

PERPETUAL MOTION The Making of a Mathematical Logician by John L. Bell Llumina Press © 2010 John L. Bell All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from both the copyright owner and the publisher. Requests for permission to make copi es of any part of this work should be mailed to Permissions Department, Llumina Press, 7915 W. McNab Rd., Tamarac, FL 33321 ISBN: 978-1-60594-589-7 (PB) Printed in the United States of America by Llumina Press PCN 2 Contents New York and Rome, 1951-53 14 The Hague, 1953-54 18 Bangkok, 1955-56 28 San Francisco, 1956-58 34 Millfield, 1958-61 54 Cambridge, 1962 93 Exeter College, Oxford, 1962-65 101 Christ Church, Oxford, 1965-68 146 London, 1968-73 178 Obituary of E. H. Linfoot 225 3 My mother in the 1940s My parents in the 1950s 4 Granddad England and I, Rendcomb, 1945 5 Myself, age 3 My mother and myself, age 3 6 Myself, age 6, with you-know who 7 Granddad Oakland and his three sons, 1938 8 The Four Marx Brothers, 1969 9 Mimi and I (The Three “Me’s”), 1969 10 Myself, 2011 11 When you’re both alive and dead, Thoroughly dead to yourself, How sweet The smallest pleasure! —Bunan Some men a forward motion love, But I by backward steps would move; And when this dust falls to the urn, In that state I came, return. -

Bottom-Up" Approach from the Theory of Meaning to Metaphysics Possible? Author(S): Haim Gaifman Reviewed Work(S): Source: the Journal of Philosophy, Vol

Journal of Philosophy, Inc. Is the "Bottom-Up" Approach from the Theory of Meaning to Metaphysics Possible? Author(s): Haim Gaifman Reviewed work(s): Source: The Journal of Philosophy, Vol. 93, No. 8 (Aug., 1996), pp. 373-407 Published by: Journal of Philosophy, Inc. Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/2941035 . Accessed: 09/01/2012 10:03 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. Journal of Philosophy, Inc. is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to The Journal of Philosophy. http://www.jstor.org _________________________ +- S -+ THE JOURNAL OF PHILOSOPHY VOLUME XCIII, NO. 8, AUGUST 1996 +- * -+ IS THE "BOTTOM-UP"APPROACH FROM THE THEORY OF MEANING TO METAPHYSICSPOSSIBLE?* t M /richael Dummett's The Logical Basis of Metaphysicsoutlines an ambitious project that has been at the core of his work dur- ing the last forty years. The project is built around a partic- ular conception of the theory of meaning (or philosophy of language), according to which such a theory should constitute the cornerstone of philosophy and, in particular, provide answers to vari- ous metaphysical questions. My aim here is a critical evaluation of some of the main features of that approach. -

Foundations of the Formal Sciences VIII

Noname manuscript No. (will be inserted by the editor) Foundations of the Formal Sciences VIII: History and Philosophy of Infinity Selected papers from a conference held at Corpus Christi College, Cambridge, England, 20 to 23 September 2013 Brendan P. Larvor · Benedikt L¨owe · Dirk Schlimm Received: date / Accepted: date The concept of infinity has fascinated philosophers and mathematicians for many centuries: e.g., the distinction between the potential and actual infinite appears in Aristotle's Physics (in his treatment of the paradoxes of Zeno) and the notion was implied in the attempts to sharpen the method of approximation (starting as early as Archimedes and running through the middle ages and into the nineteenth century). Modern mathematics opened the doors to the wealth of the realm of the infinities by means of the set-theoretic foundations of mathematics. Any philosophical interaction with concepts of infinite must have at least two aspects: first, an inclusive examination of the various branches and applications, across the various periods; but second, it must proceed in the critical light of mathematical results, including results from meta-mathematics. The conference Foundations of the Formal Sciences VIII: History & Philosophy of Infinity emphasized philosophical, empirical and historical approaches: 1. In the philosophical approach, we shall link questions about the concept of infinity to other parts of the philosophical discourse, such as ontology and epis- temology and other important aspects of philosophy of mathematics. Which types of infinity exist? What does it mean to make such a statement? How do we reason about infinite entities? How do the mathematical developments shed light on the philosophical issues and how do the philosophical issues influence the mathematical developments? B. -

ON ONTOLOGY and REALISM in MATHEMATICS HAIM GAIFMAN Philosophy Department, Columbia University

THE REVIEW OF SYMBOLIC LOGIC Volume 5, Number 3, September 2012 ON ONTOLOGY AND REALISM IN MATHEMATICS HAIM GAIFMAN Philosophy Department, Columbia University Outline The paper is concerned with the way in which “ontology” and “realism” are to be inter- preted and applied so as to give us a deeper philosophical understanding of mathematical theories and practice. Rather than argue for or against some particular realistic position, I shall be concerned with possible coherent positions, their strengths and weaknesses. I shall also discuss related but different aspects of these problems. The terms in the title are the common thread that connects the various sections. The discussed topics range widely. Certain themes repeat in different sections, yet, for most part the sections (and sometimes the subsections) can be read separately. Section 1 however states the basic position that informs the whole paper and, as such, should be read (it is not too long). The required technical knowledge varies, depending on the matter discussed. Aiming at a broader audience I have tried to keep the technical requirements at a minimum, or to supply a short overview. Material, which is elementary for some readers, may be far from elementary for others (my apologies to both). I also tried to supply information that may be of interest to everyone interested in these subjects. Section 2 illustrates the application of the proposed methodology by considering various positions, some of which represent main schools in the philosophy of mathematics. There are some technical items, but I hope that the gist of the discussion should be obvious from the more elementary examples.