Vulnerability, Resilience, and Reform: the Gcc and the Oil Price Crisis 2014–2016

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Oil and Gas Technologies Supplemental Information

Quadrennial Technology Review 2015 Chapter 7: Advancing Systems and Technologies to Produce Cleaner Fuels Supplemental Information Oil and Gas Technologies Subsurface Science, Technology, and Engineering U.S. DEPARTMENT OF ENERGY Quadrennial Technology Review 2015 Oil and Gas Technologies Chapter 7: Advancing Systems and Technologies to Produce Cleaner Fuels Oil and Gas in the Energy Economy of the United States Fossil fuel resources account for 82% of total U.S. primary energy use because they are abundant, have a relatively low cost of production, and have a high energy density—enabling easy transport and storage. The infrastructure built over decades to supply fossil fuels is the world’s largest enterprise with the largest market capitalization. Of fossil fuels, oil and natural gas make up 63% of energy usage.1 Across the energy economy, the source and mix of fuels used across these sectors is changing, particularly the rapid increase in natural gas production from unconventional resources for electricity generation and the rapid increase in domestic production of shale oil. While oil and gas fuels are essential for the United States’ and the global economy, they also pose challenges: Economic: They must be delivered to users and the markets at competitive prices that encourage economic growth. High fuel prices and/or price volatility can impede this progress. Security: They must be available to the nation in a reliable, continuous way that supports national security and economic needs. Disruption of international fuel supply lines presents a serious geopolitical risk. Environment: They must be supplied and used in ways that have minimal environmental impacts on local, national, and global ecosystems and enables their sustainability. -

The US Response to Attacks on Persian Gulf Oil Infrastructure and Strategic Implications for Petro-States

ISSUE BRIEF 10.29.19 The US Response to Attacks on Persian Gulf Oil Infrastructure and Strategic Implications for Petro-States Jim Krane, Ph.D., Wallace S. Wilson Fellow for Energy Studies Mark Finley, Fellow in Energy and Global Oil On Sept. 14, 2019, Saudi Aramco’s enormous oil tanker and its crew for two months. In oil processing plant at Abqaiq was hit in a October, Iran’s national tanker company surprise cruise missile and drone attack. reported an attack on an Iranian oil tanker Further strikes damaged facilities at the in the Red Sea.3 Khurais oil field 150 miles away. The attacks None of these disruptions had more on some of the world’s most vital pieces of than a short-lived effect on global oil prices. energy infrastructure initially knocked out Iran appears to have played a direct or 5.7 million barrels per day (Mb/d) of Saudi indirect role in the May/June tanker and oil production and 0.7 Mb/d of natural gas Saudi attacks. But the Trump administration liquids production, the largest ever outage has not, as yet, followed the guidelines in in volume terms in the modern history of oil. the 1980 Carter Doctrine, which states that Oil prices immediately jumped from $60 to Washington would use military force—if $69 per barrel. necessary—to protect its interests in the Gulf. Just over two weeks later, the sense of The US president suggested at one point urgency was gone. Saudi Aramco had fully that ultimate responsibility in dealing with restored the lost production, even as repairs the attacks rested with Saudi Arabia. -

A Case Study of Chevron Nigeria

Investing in Fragile Contexts: A Case Study of Chevron Nigeria Background to Chevron in Nigeria: Chevron is one of the world's leading integrated energy companies. Its roots go back to the formation of Pacific Coast Oil Company in 1876. That company later became Standard Oil Company of California and, subsequently, Chevron Corporation. Chevron acquired Gulf Oil Corporation in 1984, merged with Texaco (formerly The Texas Fuel Company, formed in Beaumont, Texas, in 1901) in 2001 and acquired Unocal in 2005. These mergers and acquisitions have strengthened Chevron's position as an energy industry leader, increasing its crude oil and natural gas assets around the world. Chevron is involved in virtually every facet of the energy industry. It has a diverse and highly skilled global workforce of approximately 64,700 employees. Its business operations traverse 100 countries. In 2014, Chevron's average net production was 2.571 million oil-equivalent barrels per day. About 74 percent of that production occurred outside the United States. At the end of 2014, Chevron had a global refining capacity of 1.9 million barrels of oil per day. Challenges: Nigeria is the most populous country in Africa and has the largest economy on the continent. It has an estimated population of 170million people who are from different ethnic backgrounds and speak more than 200 languages. The country has a high rate of unemployment and poverty, and outbreaks of violent, inter-ethnic conflicts are rife. Governance and transparency is sometimes a challenge. Nigeria gained its independence from Great Britain in October, 1960 and Chevron arrived in the country a year after. -

The New American Oil Boom Implications for Energy Security

The New American Oil Boom implications for energy security a project of The New American Oil Boom implications for energy security a project of copyright © 2012 securing america’s future energy. all rights reserved. Disclaimer: Although the authors and endorsers of this report have used their best efforts in its preparation, they assume no responsibility for any errors or omissions, nor any liability for damages resulting from the use of or reliance on information contained herein. The authors have sought to obtain permission from all image, data, and chart owners and apologize to any who could not be properly traced for permission and acknowledgement. Energy Security Leadership Council council co-chairs General P.X. Kelley, U.S. Marine Corps (Ret.) Frederick W. Smith 28th Commandant, U.S. Marine Corp Chairman, President and CEO, FedEx Corporation members Admiral Dennis C. Blair, U.S. Navy (Ret.) General John M. Keane, U.S. Army (Ret.) Former Director of National Intelligence and Former Vice Chief of Staff of the U.S. Army Commander in Chief, U.S. Pacific Command Admiral Timothy J. Keating, U.S. Navy (Ret.) General Bryan “Doug” Brown, U.S. Army (Ret.) Former Commander, U.S. Pacific Command Former Commander, U.S. Special Operations Command Herbert D. Kelleher Founder & Chairman Emeritus, Southwest Steve Cahillane Airlines Co. President & CEO, Coca-Cola Refreshments (CCR), The Coca-Cola Company John F. Lehman Former Secretary to the U.S. Navy Admiral Vern Clark, U.S. Navy (Ret.) Former Chief of Naval Operations General Michael E. Ryan, U.S. Air Force (Ret.) 16th Chief of Staff, U.S. -

Investment Rationale LTM EV/EBITDA 4.5X LTM Price/Earnings 8.7X at the Start of FY19-20 the E&U Team Decided to Disband Its Long- Held Synthetic U.S

RESEARCH REPORT November 9, 2019 Insert Picture in Master View Stock Rating BUY Price Target $72.00 – $89.00 Bear Price Bull Case Target Case $72.00 $80.50 $89.00 Ticker COP ConocoPhillips Market Cap (MM) $63,642 Investment Rationale LTM EV/EBITDA 4.5x LTM Price/Earnings 8.7x At the start of FY19-20 the E&U team decided to disband its long- held synthetic U.S. ETF. To do so, the team liquidated all of its 52 Week Performance holdings and identified two U.S.-based names to take active positions in: ConocoPhillips (NYSE: COP) and Kinder Morgan, Inc. 100 (NYSE: KMI). This report focuses on ConocoPhillips, and seeks to 78.3 analyze the company’s business model and explain the E&U team’s investment rationale. 75 The QUIC E&U team believes that COP has a best in-class 69.6 management team which exhibits strong capital prudence, a shareholder-friendly business model underpinned by quality assets, 50 and an all-weather balance sheet capable of generating free-cash- flow throughout the entire cycle. 25 Despite ConocoPhillips’ strengths, investors continue to discount the Nov-18 Mar-19 Jul-19 Nov-19 company’s value, largely because of COP’s infamous leverage profile during the mid 2000s energy boom and uncommon listing position TSX:COP TSX Capped Energy Index as a mega-cap pureplay E&P name. Given COP’s stark deleveraging, refined capital allocation strategy, and attractive operational characteristics, the E&U team concludes Energy & Utilities that these concerns are trivial and estimate the company’s equity value is approximately $72 - $89, a 21% - 50% premium to current Mircea Barcan market prices. -

The Deepwater Horizon Oil Spill's Impact on People's Health

THE SEA GRANT and GOMRI THE DEEPWATER HORIZON OIL SPILL’S PARTNERSHIP IMPACT ON PEOPLE’S HEALTH: The mission of Sea Grant is to enhance the practical use and INCREASES IN STRESS AND ANXIETY conservation of coastal, marine Larissa Graham, Christine Hale, Emily Maung-Douglass, Stephen Sempier, Tara Skelton, and Great Lakes resources in LaDon Swann, and Monica Wilson order to create a sustainable economy and environment. There are 33 university– The impacts of the Deepwater Horizon oil spill stretched beyond the based Sea Grant programs Gulf of Mexico’s waters, plants, animals, and habitats. It affected the throughout the coastal U.S. These programs are primarily mental health of some residents along the Gulf Coast. The impacts supported by the National varied based on what kind of job a person had, how attached they were Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration and the states to the place they lived, and how many disasters they had lived through in which the programs are prior to the spill. located. In the immediate aftermath of the Deepwater Horizon spill, BP committed $500 million over a 10–year period to create the Gulf of Mexico Research Initiative, or GoMRI. It is an independent research program that studies the effect of hydrocarbon releases on the environment and public health, as well as develops improved spill mitigation, oil detection, characterization, and remediation technologies. GoMRI is led by an independent and academic 20–member research board. The Sea Grant oil spill science outreach team identifies the best available science from projects funded by GoMRI and others, and only shares peer- reviewed research results. -

Effective Tax Rates for Oil and Gas Companies

Effective Tax Rates of Oil and Gas Companies: Cashing in on Special Treatment July 2014 Table of Contents Page Results in Brief …………………………………………………………………….. 3 Discussion ……………………………………………………………………………. 4 Conclusion …………………………………………………………………………… 6 Notes …………………………………………………………………………………… 6 U.S. Federal Effective Tax Rates, 2009-2013 …………………………… 7 Foreign Effective Tax Rates, 2009-2013 ………………………………..... 8 Deferred Tax Liabilities from Property, Plant, and Equipment in 2012 and 2013……………………………………………………………………….. 9 Appendix: Company Profiles ExxonMobil Corporation ……………………………………………......... 10 ConocoPhillips …………………………………………………………………. 12 Occidental Petroleum Corporation …………………………………….. 14 Chevron Corporation ………………………………………………………… 15 Anadarko Petroleum Corporation ………………………………………. 17 Chesapeake Energy Corporation …………………………………......... 19 EOG Resources, Inc. …………………………………………………........ 20 Devon Energy Corporation …………………………………………......... 22 Apache Corporation ………………………………………………………….. 23 Pioneer Natural Resources Company ………………………………….. 25 Continental Resources, Inc. ……………………………………………… 27 Marathon Oil Corporation …………………………………………………. 28 Hess Corporation ……………………………………………………………… 29 Range Resources Corporation ……………………………………………. 30 Plains Exploration & Production Company …………………………. 31 SandRidge Energy, Inc. ……………………………………………………. 33 Whiting Petroleum Corporation …………………………………………. 34 Denbury Resources, Inc. ………………………………………………….. 35 Noble Energy, Inc. …………………………………………………………… 36 Concho Resources Inc. …………………………………………………….. 37 Company Notes ………………………………………………………………… -

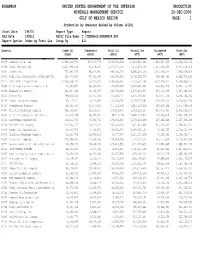

Ranking Operator by Gas 1947

PDRANKOP UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR PRODUCTION MINERALS MANAGEMENT SERVICE 22-DEC-2000 GULF OF MEXICO REGION PAGE: 1 Production by Operator Ranked by Volume (4120) Start Date : 194701 Report Type : Report End Date : 199512 ASCII File Name: C:\TIMSWork\PDRANKOP.DAT Report Option: Order by Total Gas Group By : All Operator Crude Oil Condensate Total Oil Natural Gas Casinghead Total Gas (BBLS) (BBLS) (BBLS) (MCF) (MCF) (MCF) 00078 Chevron U.S.A. Inc. 1,926,333,769 137,016,779 2,063,350,548 11,063,925,241 2,504,607,294 13,568,532,535 00689 Shell Offshore Inc. 1,417,893,524 85,274,236 1,503,167,760 7,372,318,798 2,025,230,206 9,397,549,004 00001 Conoco Inc. 797,691,267 90,614,940 888,306,207 6,665,540,300 1,270,468,340 7,936,008,640 00540 MOBIL OIL EXPLORATION & PRODUCING SOUT 323,970,684 67,931,345 391,902,029 6,452,624,776 498,954,383 6,951,579,159 00276 Exxon Mobil Corporation 1,093,558,792 56,026,660 1,149,585,452 5,223,562,198 1,323,290,927 6,546,853,125 00985 Union Exploration Partners, Ltd. 172,994,887 68,962,600 241,957,487 5,693,340,954 248,803,779 5,942,144,733 00081 Tenneco Oil Company 213,224,062 48,335,567 261,559,629 5,587,612,854 279,449,349 5,867,062,203 00040 Texaco Inc. 189,506,674 33,936,036 223,442,710 4,576,194,031 442,571,025 5,018,765,056 00114 Amoco Production Company 97,147,101 34,421,651 131,568,752 3,175,779,982 235,024,436 3,410,804,418 00167 PennzEnergy Company 191,565,059 26,157,422 217,722,481 2,812,024,858 262,674,308 3,074,699,166 00967 Atlantic Richfield Company 242,193,417 18,221,055 260,414,472 -

Historic NAME: Gulf Oil Distribution Facility STREET & NUMBER

(Oct. 1990) United States Department of the Interior National Park Service NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES REGISTRATION FoRM ~NAME 01? PRopEwry hISTORIC NAME: Gulf Oil Distribution Facility OTHER NAME/SITE NUMBER: Hickory Street Annex L~LoCATIoN STREET & NUMBER: 501 Second Avenue CITY OR TOWN: Dallas VICINny: N/A NOT FOR PUBLIcATION: N/A STATE: Texas CODE: TX COUNTy: Dallas CODE: 113 zu CODE: 75226 [3. STATE/FEDERAL AGENCY CERTIFICATION As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act, as amended, I hereby certif~’ that this (~nomination) L request for determination of eligibility) meets the documentation standards for registering propertie~s in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. In my opinion, the property ( ~ meets) (_ does not meet) the National Register criteria. I recommend that this property be considered significant (_ nationally) (_ statewide) (x locally). C_See continuation sheet for additional comments.) Signature of certil~ying official Date State Historic Preservation Officer, Texas Historical Commission - State or Federal agency and bureau In my opinion, the property _meets does not meet the National Register criteria. (_ See continuation sheet for additional comments.) — Signature of commenting or other official Date State or Federal agency and bureau [~. NATIONAL PARK SERVICE CERTIFICATION I hereby certif~’ that this property is: Signature of the Keeper Date of Action entered in the National Register — -

Energy Sustainability in the Gulf States: the Why and the How

Energy Sustainability in the Gulf States: The Why and the How Laura El-Katiri* March 2013 MEP 4 * Laura El-Katiri, Research Fellow at Oxford Institute for Energy Studies, Oxford, UK. Correspondence address: Oxford Institute for Energy Studies; 57 Woodstock Road, Oxford OX2 6FA, United Kingdom; Tel: +44 (0)1865 889134; Fax: +44 (0)1865 310527; Email: [email protected]. The author thanks Bassam Fattouh, Jonathan Stern, David Robinson, Lavan Mahadeva, and William Yong for their helpful comments on earlier drafts of this paper; Christian Bruhn for his help and comments on the logarithms drawn up for this paper; as well as a number of unnamed friends, the discussion with whom has proven invaluable for this research. All remaining errors are the author’s. The contents of this paper are the authors’ sole responsibility. They do not necessarily represent the views of the Oxford Institute for Energy Studies or any of its members. Copyright © 2013 Oxford Institute for Energy Studies (Registered Charity, No. 286084) This publication may be reproduced in part for educational or non-profit purposes without special permission from the copyright holder, provided acknowledgment of the source is made. No use of this publication may be made for resale or for any other commercial purpose whatsoever without prior permission in writing from the Oxford Institute for Energy Studies. ISBN 978-1-907555-70-1 2 Abstract For many decades, the Gulf states’ significant oil reserves have rendered the region among the most important energy suppliers in the world, and there is similar potential for the region’s natural gas reserves. -

The Petroleum Industry: Mergers, Structural Change, and Antitrust

Federal Trade Commission TIMOTHY J. MURIS Chairman MOZELLE W. THOMPSON Commissioner ORSON SWINDLE Commissioner THOMAS B. LEARY Commissioner PAMELA JONES HARBOUR Commissioner Bureau of Economics Luke M. Froeb Director Mark W. Frankena Deputy Director for Antitrust Paul A. Pautler Deputy Director for Consumer Protection Timothy A. Deyak Associate Director for Competition Analysis Pauline M. Ippolito Associate Director for Special Projects Robert D. Brogan Assistant Director for Antitrust Louis Silvia Assistant Director for Antitrust Michael G. Vita Assistant Director for Antitrust Denis A. Breen Assistant Director for Economic Policy Analysis Gerard R. Butters Assistant Director for Consumer Protection This is a report of the Bureau of Economics of the Federal Trade Commission. The views expressed in this report are those of the staff and do not necessarily represent the views of the Federal Trade Commission or any individual Commissioner. The Commission has voted to authorize staff to publish this report. Acknowledgments This report was prepared by the Bureau of Economics under the supervision of David T. Scheffman, former Director; Mary T. Coleman, former Deputy Director and Mark Frankena, Deputy Director; and Louis Silvia, Assistant Director. Bureau economists who researched and drafted this report were Jay Creswell, Jeffrey Fischer, Daniel Gaynor, Geary Gessler, Christopher Taylor, and Charlotte Wojcik. Bureau Research Analysts who worked on this project were Madeleine McChesney, Joseph Remy, Michael Madigan, Paul Golaszewski, Matthew Tschetter, Ryan Toone, Karl Kindler, Steve Touhy, and Louise Sayers. Bureau of Economics staff also acknowledge the review of drafts and many helpful comments and suggestions from members of the staff of the Bureau of Competition, in particular Phillip L. -

The Birth of the Oil Industry Main Ideas Key Terms and People 1

DO NOT EDIT--Changes must be made through “File info” CorrectionKey=TX-A Section 1 The Birth of the Oil Industry Main Ideas Key Terms and People 1. The Texas oil industry began with the discovery of a • petroleum major oil field in Corsicana. • fossil fuel 2. The Spindletop strike marked the beginning of the oil • derricks boom in Texas. • refinery Why It Matters Today • Pattillo Higgins During the 1800s Americans searched for new energy • Anthony F. Lucas sources. Use current events sources to learn about • Spindletop strike different sources of energy available today. • boom-and-bust cycle TEKS: 1A, 1C, 6A, 7A, 7B, 8A, 8B, 9A, 13C, 20C, 20D, 21A, 21B, 21C, 22A, 22D The Story Continues myNotebook Spindletop was a small hill just outside Beaumont. Although it was only 12 feet high, people often called it Big Hill. One Use the annotation tools in your eBook day Pattillo Higgins took a Sunday school class on an outing to take notes on the to Big Hill. He happened to notice gas bubbles in the spring discovery of oil at Bleed Art Guide: at the top of the hill. When Higgins poked his cane into the All bleeding art should be extended fullySpindletop to the and the bleed guide. beginning of the oil ground, gas escaped. This visit convinced Higgins that there industry in Texas. was oil under Big Hill. The Search for Oil The demand for oil had risen dramatically after scientists developed kerosene in the mid-1800s. Kerosene was a new form of fuel for light- Art and Non-Teaching Text Guide: Folios, annos, standards, non-bleeding art, etc.