Using Locative Social Media and Urban Cartographies to Identify and Locate Successful Urban Plazas

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Providence Outline Detailed

Latest Tips & Tactics for Connecting with Social Shoppers Get Your Message to Your Market and Sell More Stuff presented by Irene Williams - [email protected] ! I. Introduction A. Once Upon a Time on Instagram: A Case Study 1. Actual Food Nashville - The story of how I happened upon a pop-up brunch, Haymakers (J Michaels new brand), and master barber TJ Klausing, and ultimately became a devoted customer of all of the above B. The Current State and Latest Stats of the Digital-Social-Mobile Marketplace 1. According to a recent L2 study (L2 is a business intelligence service that tracks the digital competence of brands), department stores are expected to grow 22 percent globally over the next five years, and one key to success is enhancing traditional retail campaigns with effective digital marketing strategies. 2. The numbers for social are huge. We all need to fish where the fish are, and clearly the fish are very social. Numbers below are reflect data from 1st and 2nd quarters 2014. a) Twitter: 271 million active users / 500 million Tweets sent daily / 78% mobile b) Facebook: 1.23 billion active users / 874 million mobile / 728 million daily / Avg 20 minutes per session c) Instagram: 182 million active users / 58 million pix per day d) Pinterest: 70+ million active users / 75% mobile / Avg. 14 minutes per session e) Google+: 400 million active users / Avg 3:46 minutes per session f) YouTube: 1 billion active users per month / 6 billion hours of video watched monthly g) LinkedIn: 300 million users h) Tumblr: 199.1 visitors globally per month / 69.1 million monthly in U.S. -

Downloaded on to a Spreadsheet

Online Journal of Communication and Media Technologies Special Issue – December 2016 Location Sharing Motivations of University Students Kemal Elciyar, Anadolu University, Turkey Abstract Location sharing-check in- contains both geographical and semantic information about the visited venues, in the form tags. Many social networks like Facebook, Twitter, İnstagram, allow people to share location but main feature of Swarm and Foursquare is that. There are many motivations have investigated for identifying location based services uses: inform each other, keep track of places, appear cool, get a reward etc. The aim of this study is examining user motivations of locations based services; Swarm and Foursquare. For this purpose, a survey has been applied to university students. Results suggest that location sharing applications supply user’s need of location based socialization. 98 Online Journal of Communication and Media Technologies Special Issue – December 2016 Introduction Location sharing applications have not a long history in research. Location sharing-check in- contains both geographical and semantic information about the visited venues, in the form tags. Foursquare, Swarm etc. are location-based social network (LBSN) and allow people to share their physical location with members of their social network. İn addition, Swarm and Foursquare also have gaming features and enables people to leave geotagged messages attached to locations. Many social networks like Facebook, Twitter, İnstagram, allow people to share location but main feature of Swarm and Foursquare is that. Foursquare and Swarm which has released by same corp. is a mobile social networking application with gaming elements that is built around people’s check-ins. Unlike Foursquare Dodgeball used SMS to share location. -

Social Media & Your Business

Social Media & Your Business Who, What, When, How Sept. 17, 2014 #SmallBizMedfordNJ @Medford_NJ facebook.com/medfordbusiness Social Media & Your Business Presented by Medford Township’s Economic Development Commission (EDC) ▫ Speaker Allison Eckel, Commission member, Medford resident, owner Promotion Savvy Hosted and Sponsored by the Medford Business Association The New Way to Reach Customers Source: HubSpot.com/inbound-marketing All About the Content 4 basic steps to social media content development Mission Message Visuals Workflow Content Creation Sample business: Only the Best Builder, LLC Medford, NJ Source: Allison Eckel via Instagram Content: Mission Why are you How you Company in the interact with mission business you customers statement are in? online & off Content: Mission Why this business: He wants to deliver the best quality for all home remodeling. Mission: To be the best builder for his customers. Content: Message Call to Action Business Update Shared Experience Content Message: Call-to-Action • Leaves are dropping! Call today for your free gutter evaluation: 1-609-555-1212. • The sun is shining today, but maybe not tomorrow. The first 5 people to comment “Sun Shine On” will get 20% off gutter cleaning! Note: I made up these offers so please don’t ask Dean to honor them. Content Message: Business Update • Look for our new red and yellow trucks on the roads around #MedfordNJ. Only the Best Builder has such great trucks! • Congratulations to [Employee Name] from our framing crew: he’s a new father! We wish all the best to [Name] and his new family! Note: I made these up too. Content Message: Shared Experience • The sun is shining, the temps are cool, my truck is clean… Let’s do this! • Happiness is a clean pair of jeans, a good truck, and a true level. -

An Exploration of People's Use of Locative Media and The

Claiming Places: An Exploration of People’s Use of Locative Media and the Relationship to Sense of Place by Glen E. Farrelly A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Faculty of Information University of Toronto © Copyright by Glen E. Farrelly 2017 Claiming Places: An Exploration of People’s Use of Locative Media and the Relationship to Sense of Place Glen E. Farrelly Doctor of Philosophy Faculty of Information University of Toronto 2017 Abstract This dissertation explores the role of locative media in people’s place-making activities and sense of place. Sense of place is a human need that entails people’s meanings, memories, and feelings for a location. Recent technological and market developments have introduced powerful geographic information tools and place-related media. By identifying a user’s location, locative media deliver geographically relevant content that enable people to capture and preserve place information, virtually append it to space, and broadcast it to others. Despite locative media’s growing prominence, the influence on sense of place is not well understood. A major finding of this research is that use of locative media can contribute meaningfully to a person’s positive sense of place, including fostering existential connection. This study refutes scholarly and popular dismissals of the medium as only detracting from sense of place. Locative media was found to enable people to make spaces their own by offering geographic relevant information and experiences, recording and sharing place-related impressions, and presenting places in new and enjoyable ways, such as through defamiliarization and decommodification. -

How Location-Based Social Network Applications Are Being Used

Sean David Brennan HOW LOCATION-BASED SOCIAL NETWORK APPLICATIONS ARE BEING USED JYVÄSKYLÄN YLIOPISTO TIETOJENKÄSITTELYTIETEIDEN LAITOS 2015 ABSTRACT Brennan, Sean David How Location-Based Social Network Applications Are Being Used Jyväskylä: University of Jyväskylä, 2015, 60 p. Information Systems Science, Master’s Thesis Supervisor: Veijalainen, Jari Location-based social network applications have globally become very popular with the expansion of smartphone usage. Location-based social networks (LBSN) can be defined as a site that uses Web 2.0 technology, GPS, WiFi positioning or mobile devices to allow people to share their locations, which is referred to commonly as a check-in, and to connect with their friends, find places of interest, and leave reviews or tips on specific venues. The aim of this study was to examine how location-based social applications are being used. The methods of this study comprised of a literature review and a discussion on prior research based on a selection of user studies on location-based social networks. This study also aimed at answering a number of sub-questions on user behavior such as activity patterns, motivations for sharing location, privacy concerns, and current and future trends in the field. Twelve LBSN user behavior studies were reviewed in this study. Eight of the user studies reviewed involved the application Foursquare. Research methods on eight of the reviewed studies were studies utilizing databases of the check-ins from the application itself or utilizing Twitter in their analysis. Four of the reviewed studies were user studies involving interviews and surveys. Three main themes emerged from the articles, which were activity patterns, motivations for sharing, and privacy concerns. -

IN the UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT for the DISTRICT of DELAWARE BLACKBIRD TECH LLC D/B/A BLACKBIRD TECHNOLOGIES, Plaintiff, V

Case 1:16-cv-00585-UNA Document 1 Filed 07/08/16 Page 1 of 13 PageID #: 1 IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE DISTRICT OF DELAWARE BLACKBIRD TECH LLC d/b/a BLACKBIRD TECHNOLOGIES, Plaintiff, C.A. No. _______________ v. JURY TRIAL DEMANDED FOURSQUARE LABS, INC., Defendant. COMPLAINT FOR PATENT INFRINGEMENT Plaintiff Blackbird Tech LLC d/b/a Blackbird Technologies (“Blackbird Technologies” or “Plaintiff”) hereby alleges for its Complaint for Patent Infringement against Defendant Foursquare Labs, Inc. (“Foursquare” or “Defendant”), on personal knowledge as to its own activities and on information and belief as to all other matters, as follows: THE PARTIES 1. Plaintiff Blackbird Technologies is a limited liability company organized under the laws of Delaware, with its principal place of business located at One Boston Place, Suite 2600, Boston, MA 02108. 2. On information and belief, Defendant Foursquare is a corporation organized and existing under the laws of Delaware with its principal place of business located at 568 Broadway, 10th Floor, New York, NY 10012. JURISDICTION AND VENUE 3. This is an action for patent infringement arising under the provisions of the Patent Laws of the United States of America, Title 35, United States Code §§ 100, et seq. Case 1:16-cv-00585-UNA Document 1 Filed 07/08/16 Page 2 of 13 PageID #: 2 4. Subject-matter jurisdiction over Blackbird Technologies’ claims is conferred upon this Court by 28 U.S.C. § 1331 (federal question jurisdiction) and 28 U.S.C. § 1338(a) (patent jurisdiction). 5. This Court has personal jurisdiction over Defendant because Defendant is subject to general and specific jurisdiction in Delaware. -

Investigating User Contribution Patterns to Novel Volunteered Geographic Information Platforms

INVESTIGATING USER CONTRIBUTION PATTERNS TO NOVEL VOLUNTEERED GEOGRAPHIC INFORMATION PLATFORMS By LEVENTE JUHÁSZ A DISSERTATION PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 2018 © 2018 Levente Juhász To all who believed in me ACKNOWLEDGMENTS First and foremost, my biggest gratitude goes to my advisor, Hartwig Hochmair, for guiding me through this challenging endeavor. His uttermost patience, understanding, professionalism and the opportunities he provided were all essential for the successful completion of my program. I am truly grateful for this. I also thank wholehearteadly all labmates, colleagues, fellow scientists, anonymous peer-reviewers, committee members, students and everyone I interacted with in any form during the past few years. Their figures stand in front of me, as either inspiration or negative example. Both types were equally needed for my academic development and for becoming the person who I am today. Lastly, on the most personal level humanly possible, I thank my family and the few special friends I have. They provided me with their unconditional love, which one cannot take for granted. Without their love, this work would have not been possible. Words cannot possibly express how much this means to me. 4 TABLE OF CONTENTS page ACKNOWLEDGMENTS .................................................................................................. 4 LIST OF TABLES ........................................................................................................... -

Betekenis Van Swarm Binnen De Mobile Youth Culture Populariteit En Privacy Op Swarm Wetenschappelijke Verhandeling Aantal Woorden: 23 732

Betekenis van Swarm binnen de Mobile Youth Culture Populariteit en privacy op Swarm Wetenschappelijke verhandeling Aantal woorden: 23 732 Ineke Boelens Stamnummer: 01204750 Promotor: Prof. dr. Ralf de Wolf Masterproef voorgelegd voor het behalen van de graad master in de richting Communicatiewetenschappen afstudeerrichting Media, Maatschappij en Beleid Academiejaar: 2016 – 2017 2 3 4 Abstract Toegenomen informatietechnologieën leidden de laatste jaren tot de komst van Location Based Social Networks (LBSN’s) die het gebruikers mogelijk maken om de locaties te delen waar ze zich op dat moment bevinden. Jongeren maken hier gretig gebruik van, aangezien zij de dag van vandaag nauwelijks nog zonder hun smartphone kunnen. Men spreekt in de literatuur zelfs over een Mobile Youth Culture (Castells, Fernandez- Ardevol, Qiu & Sey, 2007), waarbij men ervan uitgaat dat jongeren een eigen cultuur ontwikkeld hebben rond hun mobiele toestel en mobiele communicatie. Een van de meest gebruikte LBSN-applicaties bij jongeren in België is Swarm, een spin-off van het beter bekende Foursquare. Aangezien deze applicatie nog niet zo lang bestaat, zijn hier weinig studies over te vinden. Het doel van deze paper is om de betekenis die aan Swarm gegeven wordt binnen de MYC te achterhalen, waarbij de aspecten privacy en status/populariteit onderzocht worden. Dit gebeurt aan de hand van een grondige literatuurstudie, waarin we de MYC schetsen en Swarm hierbinnen plaatsen en stilstaan bij eerder onderzoek over privacy en status/populariteit bij jongeren in de context van Social Network Sites. Via focusgroepen en diepte-interviews trachtten we een antwoord te vinden op onze onderzoeksvragen. We vonden dat jongeren zowel aan individueel als collaboratief privacy- management doen en dat ze te maken krijgen met heel wat uitdagingen rond hun privacy. -

On Foursquare Day

FIRST SOCIAL MEDIA HOLIDAY GOES GLOBAL San Francisco “checks-in” on Foursquare Day SAN FRANCISCO, CA – April 6, 2010, Pacific Catch announced that on April 16th, its 9th Avenue restaurant will host what will be the largest “Foursquare Day Swarm Badge” event in the Bay Area. The Pacific Catch 9th Avenue location in the Inner Sunset, known for its fresh, cravable seafood, full bar and happy hour, will be the place for social media mavens and tipsters to “check-in” on April 16th to obtain the much coveted Foursquare “Swarm Badge.” Food and drink specials will take place from 4:00 pm till 7:00 pm with a live check in via Skype at 6:00 pm, with Foursquare Day creator, Nate Bonilla-Warford in Tampa. What is Foursquare? Foursquare is a mobile, location sharing, social media tool, in which users earn points as they check in at venues they visit during the day, with an option to broadcast their location to friends via Twitter, to let others join them there. Foursquare is half scavenger hunt, half flash mob, as users compete by earning points and badges depending on the frequency, the locations and the types of venues at which they check in. For example, the most frequent visitor to check in at any given venue is awarded the “mayor” badge of that location. The “Swarm Badge”, is awarded to a group when 50 people “check-in” at the same location within a three-hour time-frame. How can you be a part of Foursquare Day? Check out the Foursquare Day Website and join the “San Francisco Foursquare Day Swarm” City Challenges: San Francisco challenges Portland for the most swarm check-ins. -

Casual Dining Restaurant Loyalty Index

Casual Dining Restaurant Loyalty Index 2018 State of the Casual Dining Industry Casual dining is in a transitional period. The challenges that have tested retailers like Kmart and Macy’s, such as over-retailing and change in customer spending habits—are now affecting the dining industry, contributing to sales and closures throughout the past two years. Consumers also have more alternatives to dining out than ever before. Innovative technology has inspired a proliferation of food delivery services like Blue Apron, and on-demand delivery like GrubHub or UberEATS. Synchronously, up-and-coming fast casual chains like Shake Shack are on the rise, many of which are known for their cult following and dedication to more sustainable food sources. One of the above nuances alone can change the market entirely—together, they present an multifaceted challenge. By analyzing foot traffic patterns from a nationally representative group of U.S. consumers who make up our always-on foot traffic panel, Foursquare is uniquely equipped to help casual dining chains succeed by understanding dining trends and shifts in consumption. Furthermore, because Foursquare has a deep understanding of where people go in the real world, we can measure loyalty based on customer behavior rather than perceptions, providing an accurate measure for business health and true loyalty. In 2017, we debuted our first-ever Quick Service Restaurant (QSR) Loyalty Index, ranking the top QSRs in the U.S. and their customers’ loyalty. Now, we’re excited to introduce our first annual Casual Dining Restaurants (CDR) Loyalty Index using the same methodology. In this report, you’ll find.. -

In Latam Study

IMS MOBILE IN LATAM STUDY 2ND EDITION SEPTEMBER 2016 IMS MOBILE IN LATAM STUDY TABLE OF CONTENTS 2016 Methodology 03 Respondent Profile 04 Connectivity 05 Smartphone Usage 12 Tablet Usage 22 App Usage 31 IMS Reach 41 Highlights 44 IMS App Profile 48 IMS MOBILE IN LATAM STUDY RESEARCH METHODOLOGY 2016 SAMPLE MARGIN OF ERROR SIZES COUNTRY SAMPLE SIZE (95% CONFIDENCE LEVEL) Total 4.851 +/- 1.4 percentage points 832 +/- 3.2 percentage points 805 +/- 3.5 percentage points 807 +/- 3.4 percentage points 804 +/- 3.5 percentage points 803 +/- 3.5 percentage points 800 +/- 3.5 percentage points METHODOLOGY SAMPLE Participants were smartphone and tablet Online survey panelists in six countries were owners who use mobile apps. contacted via email to complete a 10 minute REQUIRMENTS survey about device ownership, app usage, and behaviors. The survey fieldwork was conducted TIMING September 2nd - 9th, 2016 03 IMS MOBILE IN LATAM STUDY RESPONDENT PROFILE 2016 GENDER FEMALE MALE EMPLOYMENT Full-time 44% 49% 51% STATUS Part-time 11% Self-employed 16% AGE 15-24 29% Not currently employed 9% 25-34 29% Homemaker 3% 35-44 21% Retired 3% 45-54 12% Student 12% 55+ 9% Other 2% 58% OF THE RESPONDENTS HAVE LESS THAN 35 YEARS AND +70% ARE EMPLOYED 04 CONNECTIVITY IMS MOBILE IN LATAM STUDY 2ND EDITION CONNECTIVITY IMS MOBILE IN LATAM STUDY 2016 71.7% 68.0% 58.2% 59.6% 56.1% 57.8% 56.1% 51.1% OF LATAM POPULATION IS ALREADY CONNECTED Digital is already a large reach builder in Latin America. At least half of the TOTAL BRAZIL MEXICO ARGENTINA COLOMBIA PERU CHILE population in each of the countries surveyed is already connected –in some cases already above 70%. -

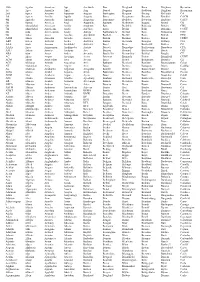

10Th 1St 2Nd 3Rd 4Th 5Th 6Th 7Th 8Th 9Th A&M A&P AAA

10th Agatha Amadeus Apr Auerbach Barr Berglund Boca Brigham Byzantine 1st Agee Amarillo April Aug Barrett Bergman Bodleian Brighton Byzantium 2nd Agnes Amazon Aquarius Augean Barrington Bergson Boeing Brillouin CA 3rd Agnew Amelia Aquila Augusta Barry Bergstrom Boeotia Brindisi CACM 4th Agricola Amerada Aquinas Augustan Barrymore Berkeley Boeotian Brisbane CATV 5th Agway America Arab Augustine Barstow Berkowitz Bogota Bristol CB 6th Ahmadabad American Arabia Augustus Bart Berkshire Bohemia Britain CBS 7th Ahmedabad Americana Arabic Aurelius Barth Berlin Bohr Britannic CCNY 8th Aida Americanism Araby Auriga Bartholomew Berlioz Bois Britannica CDC 9th Aides Ames Arachne Auschwitz Bartlett Berlitz Boise British CEQ A&M Aiken Ameslan Arcadia Austin Bartok Berman Bolivia Briton CERN A&P Aileen Amherst Archer Australia Barton Bermuda Bologna Brittany CIA AAA Ainu Amman Archibald Australis Basel Bern Bolshevik Britten CO AAAS Aires Ammerman Archimedes Austria Bassett Bernadine Bolshevism Broadway CPA AAU Aitken Amoco Arcturus Ave Batavia Bernard Bolshevist Brock CRT ABA Ajax Amos Arden Aventine Batchelder Bernardino Bolshoi Broglie CT AC Akers Ampex Arequipa Avery Bateman Bernardo Bolton Bromfield CUNY ACM Akron Amsterdam Ares Avesta Bates Bernet Boltzmann Bromley CZ ACS Alabama Amtrak Argentina Avis Bathurst Bernhard Bombay Brontosaurus Cabot AK Alabamian Amy Argive Aviv Bator Bernice Bonaparte Bronx Cadillac AL Alameda Anabaptist Argonaut Avogadro Battelle Bernie Bonaventure Brooke Cady AMA Alamo Anabel Argonne Avon Baudelaire Berniece Boniface