China's Efforts to Legitimize the Implementation of the Belt And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Grazie a Tutti!

GRAZIE A TUTTI! ANCHE QUEST’ANNO ABBIAMO REALIZZATO IL PIU’ GRANDE EVENTO DELL’ANNO! GRAZIE AGLI ARTISTI… A LUCA & PAOLO, A BRUNO SANTORI E LA SUA ORCHESTRA, ALLE CASE DISCOGRAFICHE… A TUTTO LO STAFF DI RADIO ITALIA… A TUTTI VOI… MA NON SOLO… RADIOITALIALIVE - IL CONCERTO HA SUONATO ANCHE GRAZIE A… CHEBANCA AMICA CHIPS - TOYOTA - CONNETTIVINA - UNIPEGASO - LEVI’S - RIMMEL - FASTWEB - COOP - SORRISI E CANZONI TV - ATM - CHI CLASS TV - FIUGGI - TERRAFERMA VENERANDA FABBRICA DEL DUOMO - HOTEL ME MILAN - IL DUCA SPUMANTI ANGELO BORTOLIN - METEO.IT LA TUA INFORMAZIONE QUOTIDIANA DAL 1989 Anno XXVI Giovedì 04/06/2015 N°102 IERI SERA LA 28ª EDIZIONE DEL PREMIO DI TVN MEDIA GROUP A Samsung ‘Hearing Hands’ l’International GrandPrix Advertising Strategies 2015 Il progetto firmato da Leo Burnett Istanbul e prodotto da Casta Diva Group è stato il più votato dal pubblico del Barclays Teatro Nazionale [ pagine 11 e 12 ] • • • • • ALL’INTERNO • • • • • IN TOUR, SU STAMPA E AFFISSIONI GENNAIO-APRILE 2015 LA NUOVA BMW SERIE 2 GRAN TOURER ON AIR CON M&C SAATCHI Gingerino Mix FCP, nei primi pag. 13 in comunicazione quattro mesi adv GIRO DI POLTRONE IN IPG MEDIABRANDS con Armando Testa su stampa a -6,4% pag. 18 Recoaro riporta il brand in adv con Per i quotidiani -6,9% a fatturato e DENTRO EXPO il lancio di un nuovo cocktail al -3,1% a spazio. Periodici in calo a CON LEGO SI COSTRUISCE A MILANO gusto Arancia e Ginseng fatturato del 5,5% e a spazio del 4,5% LA TORRE PIÙ ALTA DEL MONDO [ pag. -

N°137 July 2015

N°137 July 2015 348 of you – directors, producers, documentary-makers, journalists – have sent us your films. For one week the selection jury worked together in Casablanca, guests of our partner, 2M. On the pages of your favourite newsletter you can read about the films which have moved forward to the final phase of the 19th PriMed. The choice for the Mediterranean Short Film category will be announced in next month's Letter. Also in this issue, the latest Mediterranean broadcasting news gleaned especially for you. Happy reading. Méditerranée Audiovisuelle-La Lettre. Dépôt Légal 12 février 2015. ISSN : 1634-4081. Tous droits réservés Directrice de publication : Valérie Gerbault Rédaction : Valérie Gerbault, Séverine Miot et Leïla Porcher CMCA - 96 La Canebière 13001 Marseille Tel : + 33 491 42 03 02 Fax : +33 491 42 01 83 http://www.cmca-med.org - [email protected] Le CMCA est soutenu par les cotisations de ses membres, la Ville de Marseille, le Département des Bouches du Rhône et la Région Provence Alpes Côte d'Azur. 1 CONTENTS HEADLINES 3 PriMed 2015 – the official selection The official selection 6 “Mediterranean Issues” 7 “Mediterranean Memories” 10 “Mediterranean Art, Heritage and Culture” 13 “First Film” 16 “Mediterranean Multimedia Award” 18 LIFE IN THE CHANNELS 21 PROGRAMMES 23 ECONOMY 24 CINEMA 25 FESTIVAL 28 Festival of the month THE EURO-MEDITERRANEAN PERSPECTIVE 29 STOP PRESS 30 2 HEADLINES The PriMed 2015 selection For a week in June, the Moroccan channel 2M, a CMCA member, welcomed the PriMed selection jury to Casablanca. The screenings took place in the channel's main auditorium. -

Kasia Kieli President and Managing Director Discovery Networks Central & Eastern Europe, Middle East and Africa

Kasia Kieli President and Managing Director Discovery Networks Central & Eastern Europe, Middle East and Africa Kasia Kieli is President and Managing Director for Discovery Networks Central & Eastern Europe, Middle East & Africa (CEEMEA), a division of Discovery Communications, the leader in global entertainment. Based in Discovery Networks CEEMA’s headquarters in Warsaw, Kasia Kieli has strategic management responsibility for Discovery's operations in the region, which today encompasses 112 countries and territories across three continents, with 12 offices, including: Munich, Dubai, London, Amsterdam, Sofia, Budapest, Prague, Istanbul, Moscow and Bucharest. In each of these markets, Discovery broadcasts up to 21 channels, reaching 590 million viewers. Kieli joined Discovery and founded the Polish office in 2000. During her 16 years at Discovery, she has launched more than 14 channel brands across 100+ markets and has transformed Discovery CEEMEA from being a predominantly pay-TV business, to a more complex organization that includes a growing portfolio of free-to-air channels, such as Dmax in Germany, Fatafeat and Quest Arabiya in the Middle East and TLC in Turkey. Under her leadership, the company has also entered into strategic partnerships that have expanded the business and increased Discovery’s presence in key markets such as Russia, Poland, Turkey and the Middle East. Kieli also successfully led a number of mergers and acquisitions in the region, including the acquisition of Dubai-based media company Takhayal Entertainment. She also successfully oversaw the Discovery-Eurosport integration process across the region, after Discovery Communications’ acquisition of Eurosport in 2015. Kieli is considered one of the most renowned media experts in the region. -

Stream Name Category Name Coronavirus (COVID-19) |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT ---TNT-SAT ---|EU| FRANCE TNTSAT TF1 SD |EU|

stream_name category_name Coronavirus (COVID-19) |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT ---------- TNT-SAT ---------- |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT TF1 SD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT TF1 HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT TF1 FULL HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT TF1 FULL HD 1 |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT FRANCE 2 SD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT FRANCE 2 HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT FRANCE 2 FULL HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT FRANCE 3 SD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT FRANCE 3 HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT FRANCE 3 FULL HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT FRANCE 4 SD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT FRANCE 4 HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT FRANCE 4 FULL HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT FRANCE 5 SD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT FRANCE 5 HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT FRANCE 5 FULL HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT FRANCE O SD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT FRANCE O HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT FRANCE O FULL HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT M6 SD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT M6 HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT M6 FHD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT PARIS PREMIERE |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT PARIS PREMIERE FULL HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT TMC SD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT TMC HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT TMC FULL HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT TMC 1 FULL HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT 6TER SD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT 6TER HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT 6TER FULL HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT CHERIE 25 SD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT CHERIE 25 |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT CHERIE 25 FULL HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT ARTE SD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT ARTE FR |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT RMC STORY |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT RMC STORY SD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT ---------- Information ---------- |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT TV5 |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT TV5 MONDE FBS HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT CNEWS SD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT CNEWS |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT CNEWS HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT France 24 |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT FRANCE INFO SD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT FRANCE INFO HD -

TV News Channels in Europe: Offer, Establishment and Ownership European Audiovisual Observatory (Council of Europe), Strasbourg, 2018

TV news channels in Europe: Offer, establishment and ownership TV news channels in Europe: Offer, establishment and ownership European Audiovisual Observatory (Council of Europe), Strasbourg, 2018 Director of publication Susanne Nikoltchev, Executive Director Editorial supervision Gilles Fontaine, Head of Department for Market Information Author Laura Ene, Analyst European Television and On-demand Audiovisual Market European Audiovisual Observatory Proofreading Anthony A. Mills Translations Sonja Schmidt, Marco Polo Sarl Press and Public Relations – Alison Hindhaugh, [email protected] European Audiovisual Observatory Publisher European Audiovisual Observatory 76 Allée de la Robertsau, 67000 Strasbourg, France Tel.: +33 (0)3 90 21 60 00 Fax. : +33 (0)3 90 21 60 19 [email protected] http://www.obs.coe.int Cover layout – ALTRAN, Neuilly-sur-Seine, France Please quote this publication as Ene L., TV news channels in Europe: Offer, establishment and ownership, European Audiovisual Observatory, Strasbourg, 2018 © European Audiovisual Observatory (Council of Europe), Strasbourg, July 2018 If you wish to reproduce tables or graphs contained in this publication please contact the European Audiovisual Observatory for prior approval. Opinions expressed in this publication are personal and do not necessarily represent the view of the European Audiovisual Observatory, its members or the Council of Europe. TV news channels in Europe: Offer, establishment and ownership Laura Ene Table of contents 1. Key findings ...................................................................................................................... -

Australia ########## 7Flix AU 7Mate AU 7Two

########## Australia ########## 7Flix AU 7Mate AU 7Two AU 9Gem AU 9Go! AU 9Life AU ABC AU ABC Comedy/ABC Kids NSW AU ABC Me AU ABC News AU ACCTV AU Al Jazeera AU Channel 9 AU Food Network AU Fox Sports 506 HD AU Fox Sports News AU M?ori Television NZ AU NITV AU Nine Adelaide AU Nine Brisbane AU Nine GO Sydney AU Nine Gem Adelaide AU Nine Gem Brisbane AU Nine Gem Melbourne AU Nine Gem Perth AU Nine Gem Sydney AU Nine Go Adelaide AU Nine Go Brisbane AU Nine Go Melbourne AU Nine Go Perth AU Nine Life Adelaide AU Nine Life Brisbane AU Nine Life Melbourne AU Nine Life Perth AU Nine Life Sydney AU Nine Melbourne AU Nine Perth AU Nine Sydney AU One HD AU Pac 12 AU Parliament TV AU Racing.Com AU Redbull TV AU SBS AU SBS Food AU SBS HD AU SBS Viceland AU Seven AU Sky Extreme AU Sky News Extra 1 AU Sky News Extra 2 AU Sky News Extra 3 AU Sky Racing 1 AU Sky Racing 2 AU Sonlife International AU Te Reo AU Ten AU Ten Sports AU Your Money HD AU ########## Crna Gora MNE ########## RTCG 1 MNE RTCG 2 MNE RTCG Sat MNE TV Vijesti MNE Prva TV CG MNE Nova M MNE Pink M MNE Atlas TV MNE Televizija 777 MNE RTS 1 RS RTS 1 (Backup) RS RTS 2 RS RTS 2 (Backup) RS RTS 3 RS RTS 3 (Backup) RS RTS Svet RS RTS Drama RS RTS Muzika RS RTS Trezor RS RTS Zivot RS N1 TV HD Srb RS N1 TV SD Srb RS Nova TV SD RS PRVA Max RS PRVA Plus RS Prva Kick RS Prva RS PRVA World RS FilmBox HD RS Filmbox Extra RS Filmbox Plus RS Film Klub RS Film Klub Extra RS Zadruga Live RS Happy TV RS Happy TV (Backup) RS Pikaboo RS O2.TV RS O2.TV (Backup) RS Studio B RS Nasha TV RS Mag TV RS RTV Vojvodina -

TV Channel Monitoring

TV Channel Monitoring The channels below are monitored in real- time, 24/7. United States 247 channels NATIONAL A&E Comedy Central Fuse ABC CW FX ABC Family Destination America GAC AHC Discovery Galavision (GALA) AMC Discovery Fit & Health Golf Channel Animal Planet Discovery ID GSN BBC America Disney Channel Hallmark Channel BET DIY HGTV Big Ten Network E! History Channel Biography Channel ESPN HLN Bloomberg News ESPN 2 HSN BRAVO ESPN Classic IFC Cartoon Network ESPN News ION CBS ESPN U Lifetime CBS Sports Food Network LOGO Cinemax East Fox 5 MLB CMT Fox Business MSG Network CNBC Fox News MSNBC CNBC World Fox Sports 1 MTV CNN Fox Sports 2 MTV2 My9 Science Channel Travel Channel National Geographic ShowTime East truTV NBA Spike TV TV1 NBC SyFy TV Guide NBC Sports (Versus) TBN TV Land NFL TBS Univision NHL TCM USA Nickelodeon Telemundo VH1 Nicktoons Tennis Channel VH1 Classic OLN The Cooking VICELAND Oprah Winfrey Net. Channel WE Ovation The Hub WGN America Oxygen Time Warner Cable WLIW QVC TLC YES REELZ TNT New York ABC (WABC) Fox (WNYW) Univision (WXTV) CBS (WCBS) MyNetworkTV (WWOR) CW (WPIX) NBC (WNBC) Los Angeles ABC (KABC) CW (KTLA) NBC (KNBC) CBS (KCBS) FOX (KTTV) Univision (KMEX) Baltimore ABC (WMAR-DT) Fox (WBFF-DT) NBC (WBAL-DT CBS (WJZ-DT) MyNetworkTV CW (WNUV-DT) (WUTB-DT) Chicago ABC (WLS-DT) Fox (WFLD-DT) Univision (WGBO- CBS (WBBM-DT) NBC (WMAQ-DT) DT) CW (WGN-DT) San Diego ABC (KGTV) FOX (KSWB) The CW (KFMB) CBS (KFMB) NBC (KNSD) Univision (KBNT) The United Kingdom 74 Channels 4Music Home Nick Toons 5 star Horror Channel -

Broadcast and on Demand Bulletin Issue Number

Issue 347 of Ofcom’s Broadcast and On Demand Bulletin 5 February 2018 Issue number 347 5 February 2018 Issue 347 of Ofcom’s Broadcast and On Demand Bulletin 5 February 2018 Contents Introduction 3 Notice of Sanction February Box Al Arabiya News, 27 February 2016 5 Note to Broadcasters Monitoring of diversity and equal opportunities in broadcasting 7 Broadcast Standards cases In Breach Cops UK: Bodycam Squad Dave, 17 November 2017, 20:00 and 19 November 2017, 11:00 9 Rickie, Melvin & Charlie in the Morning Kiss, 20 November 2017, 08:10 12 Tameside Today Tameside Radio, 19 October 2017, 12:50 14 To the Point JUS Punjabi, 2 November 2017, 19:00 16 Broadcast Fairness and Privacy cases Not Upheld Complaint by Mrs Allison Edwards, made on her own behalf and on behalf of her son Dispatches: Trump, the Doctor and the Vaccine Scandal, Channel 4, 8 May 2017 18 Complaint by Lidl UK GmbH Supershoppers, Channel 4, 6 June 2017 29 Tables of cases Investigations Not in Breach 41 Complaints assessed, not investigated 42 Complaints outside of remit 51 BBC First 52 Investigations List 54 Issue 347 of Ofcom’s Broadcast and On Demand Bulletin 5 February 2018 Introduction Under the Communications Act 2003 (“the Act”), Ofcom has a duty to set standards for broadcast content to secure the standards objectives1. Ofcom also has a duty to ensure that On Demand Programme Services (“ODPS”) comply with certain standards requirements set out in the Act2. Ofcom reflects these requirements in its codes and rules. The Broadcast and On Demand Bulletin reports on the outcome of Ofcom’s investigations into alleged breaches of its codes and rules, as well as conditions with which broadcasters licensed by Ofcom are required to comply. -

October 2015 in Partnership with in Partnership With

October 2015 In partnership with In partnership with pOFC DTVE CIA Oct15.indd 1 25/09/2015 17:00 SNI2175_SNI-MIPCOMpXX DTVE CIA Oct15.indd 2015-Trade 1 Ads_DigitalTVEurope_216mmx303mm_1.indd 1 11/09/20159/9/15 4:59 17:56 PM Digital TV Europe October 2015 October 2015 Contents In partnership with In partnership with pOFC DTVE CIA Oct15.indd 1 25/09/2015 17:00 4K Initiative of the Year 4 Cloud TV Innovation of the Year 8 Social TV Innovation of the Year 12 Industry Innovation of the Year 14 Best New Channel Launch 16 MCN of the Year 18 Best International TV Networks Group 20 Channel of the Year 22 TV Technology Award (content discovery) 24 TV Technology Award (second-screen experience) 28 TV Technology Award (service-enabling technology) 32 Multiscreen TV Award 36 Pay TV Service of the Year 38 Best Content Distributor 42 International Production Company of the Year 44 Best Series Launch of the Year 46 Champagne Multiscreen TV Award Social TV Innovation of the Associate Sponsors Reception Sponsor Sponsor Year Category Sponsor EUROPE EUROPE p01 Contents DTVE CIA Oct15v2st.indd 1 25/09/2015 21:13 This month > Editor’s note Digital TV Europe October 2015 Issue no 321 Rewarding initiative Published By: Informa Telecoms & Media Maple House 149 Tottenham Court Road Content Innovation Awards is a new initiative from Digital TV London W1T 7AD The Europe in partnership with our sister publication Television Busi- Tel: +44 (0) 20 7017 5000 ness International (TBI), that is designed to celebrate some of the great innova- Fax: +44 (0) 20 7017 4953 tions from content providers, distributors and technology companies that are Website: www.digitaltveurope.net helping transform the way we produce, distribute and consume TV. -

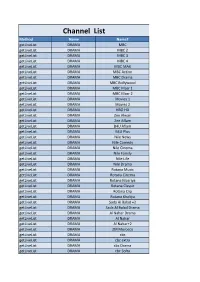

Channel List

Channel List Method Name Name2 getLiveList DRAMA MBC getLiveList DRAMA MBC 2 getLiveList DRAMA MBC 3 getLiveList DRAMA MBC 4 getLiveList DRAMA MBC MAX getLiveList DRAMA MBC Action getLiveList DRAMA MBC Drama getLiveList DRAMA MBC Bollywood getLiveList DRAMA MBC Masr 1 getLiveList DRAMA MBC Masr 2 getLiveList DRAMA Movies 1 getLiveList DRAMA Movies 2 getLiveList DRAMA HBO HD getLiveList DRAMA Zee Alwan getLiveList DRAMA Zee Aflam getLiveList DRAMA B4U Aflam getLiveList DRAMA B4U Plus getLiveList DRAMA Nile News getLiveList DRAMA Nile Comedy getLiveList DRAMA Nile Cinema getLiveList DRAMA Nile Family getLiveList DRAMA Nile Life getLiveList DRAMA Nile Drama getLiveList DRAMA Rotana Music getLiveList DRAMA Rotana Cinema getLiveList DRAMA Rotana Masriya getLiveList DRAMA Rotana Classic getLiveList DRAMA Rotana Clip getLiveList DRAMA Rotana Khalijia getLiveList DRAMA Sada Al Balad +2 getLiveList DRAMA Sada Al Balad Drama getLiveList DRAMA Al Nahar Drama getLiveList DRAMA Al Nahar getLiveList DRAMA Al Nahar+2 getLiveList DRAMA 2M Morocco getLiveList DRAMA cbc getLiveList DRAMA cbc extra getLiveList DRAMA cbc Drama getLiveList DRAMA cbc Sofra getLiveList DRAMA Abu Dhabi getLiveList DRAMA Abu Dhabi Drama getLiveList DRAMA Abu Dhabi Emarat getLiveList DRAMA Melody classic getLiveList DRAMA Al kahera Walnas 2 getLiveList DRAMA Dubai One getLiveList DRAMA Dubai getLiveList DRAMA Sama Dubai getLiveList DRAMA Noor Dubai getLiveList DRAMA iFilm getLiveList DRAMA Albait Baitak Cinema getLiveList DRAMA Nat Geo AD getLiveList DRAMA Quest arabiya getLiveList -

Elife 150 High Definition Channels

eLife 150 High Definition Channels New STB Channel Name Language Genre Channel Number 1 Information Channel HD English Info 2 Etisalat Promotions English Info 4 eLife How-To English Info 11 Abu Dhabi TV HD Arabic General 12 Al Emarat TV HD Arabic General 13 Abu Dhabi Drama HD Arabic General 15 Baynounah TV HD Arabic Entertainment 22 Dubai Al Oula HD Arabic General 23 SAMA Dubai HD Arabic General 24 Noor Dubai HD Arabic General 33 Sharjah TV HD Arabic General 34 Sharqiya from Kalba HD Arabic General 63 Qatar TV HD Arabic General 64 Al Rayyan HD Arabic General 79 LBC Sat HD Arabic General 151 MBC 1 HD Arabic Entertainment 152 MBC Drama HD Arabic Entertainment 156 Alaraby TV HD Arabic General 159 Rotana Masriya HD Arabic General 161 Rotana Classic HD Arabic General 171 OSN Yahala HD Arabic Entertainment 172 OSN Yahala HD +2 Arabic Entertainment 173 OSN Yahala Drama HD Arabic Entertainment 174 OSN Yahala Shabab HD Arabic Entertainment 180 Dubai 'One HD English General 181 MBC 4 HD English Entertainment 182 MBC Action HD English Entertainment 188 Star World HD English General 206 NHK World HD Japanese General 207 High TV 3D English General ©2016 Etisalat.ae Page 1 of 5 eLife 150 High Definition Channels New STB Channel Name Language Genre Channel Number 223 France 2 HD French Entertainment 226 TV5 Monde Orient HD French General 259 Zee TV HD Hindi Entertainment 304 Majid Kids TV HD Arabic Kids 319 Disney channel HD English Kids 322 Cinemachi Kids English Movies 323 OSN Movies Kids HD English Movies 329 Nickelodeon HD English Kids 333 e-junior -

Vmaxtv GO Channel List

VmaxTV GO Channel List Order service from https://japannettv.com/wpshop/index.php/vmaxtv-go/ Android app available from https://play.google.com/store/apps/details?id=com.vmaxtvgo.vmaxtvgoiptvbox LIVE TV Sports TV (490) Sports VIP TV (263) Arabic TV (386) Arabic VIP TV (78) Arabic Kids TV(25) Arabic Religious TV (41) Arabic News TV (35) Bulgarian TV (105) UK TV (188) USA TV (120) Canadian TV (90) Afghan TV (39) Asian TV (26) Indian TV (158) Pakistani TV (59) Bengali TV (42) Africa TV (215) Albanian TV (55) Belgium TV (15) French TV (74) Farsi TV (86) German TV (82) Greek TV (90) Italian TV (112) Portuguese TV (67) Spanish TV (70) Brazilian TV (207) Latino TV (99) Latino VIP TV (216) Mexican TV (57) Caribbean TV (99) Turkish TV (125) Kurdish TV (44) Dutch TV (42) Czech TV (74) EX-YU TV (207) Polish TV (57) Scandinavian TV (52) Romanian TV (51) Russian TV (131) Ukrainian TV (51) MOVIES Arabic Movies (177) English Movies (1180) English Classic AR Sub (211) English Movies AR Sub (753) International Movies AR Sub (58) Asian Movies AR Sub (134) Bollywood Movies AR Sub (171) Bollywood Movies (279) Turkish Movies (50) French Movies (87) German Movies (40) Italian Movies (83) Cartoon Movies (190) Cartoon Movies AR Sub (99) SERIES Arabic Series (87) English Series (104) CATCH UP Sports VIP TV (12) Bulgarian TV (16) UK TV (24) USA TV (15) Greek TV (3) 57 Groups 17430 Streams 2019 12 10 LIVE TV Sports TV AR: Al Kass Sports 1 HD AR: Sharjah Sport HD AR: Jordan Sport HD IN: STAR SPORTS 2 AR: Al Kass Sports 2 HD AR: Sharjah Sports AR: Jordan Sport IN: