Thomas Lindblad

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bernard Thomas Volume 1 Introduction by Alfredo M

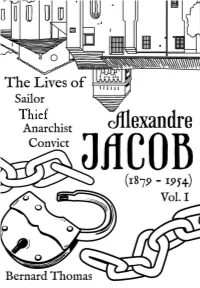

Thief Jacob Alexandre Marius alias Escande Attila George Bonnot Féran Hard to Kill the Robber Bernard Thomas volume 1 Introduction by Alfredo M. Bonanno First Published by Tchou Éditions 1970 This edition translated by Paul Sharkey footnotes translated by Laetitia Introduction by Alfredo M. Bonanno translated by Jean Weir Published in September 2010 by Elephant Editions and Bandit Press Elephant Editions Ardent Press 2013 introduction i the bandits 1 the agitator 37 introduction The impossibility of a perspective that is fully organized in all its details having been widely recognised, rigor and precision have disappeared from the field of human expectations and the need for order and security have moved into the sphere of desire. There, a last fortress built in fret and fury, it has established a foothold for the final battle. Desire is sacred and inviolable. It is what we hold in our hearts, child of our instincts and father of our dreams. We can count on it, it will never betray us. The newest graves, those that we fill in the edges of the cemeteries in the suburbs, are full of this irrational phenomenology. We listen to first principles that once would have made us laugh, assigning stability and pulsion to what we know, after all, is no more than a vague memory of a passing wellbeing, the fleeting wing of a gesture in the fog, the flapping morning wings that rapidly ceded to the needs of repetitiveness, the obsessive and disrespectful repetitiveness of the bureaucrat lurking within us in some dark corner where we select and codify dreams like any other hack in the dissecting rooms of repression. -

Anarcho-Syndicalism in the 20Th Century

Anarcho-syndicalism in the 20th Century Vadim Damier Monday, September 28th 2009 Contents Translator’s introduction 4 Preface 7 Part 1: Revolutionary Syndicalism 10 Chapter 1: From the First International to Revolutionary Syndicalism 11 Chapter 2: the Rise of the Revolutionary Syndicalist Movement 17 Chapter 3: Revolutionary Syndicalism and Anarchism 24 Chapter 4: Revolutionary Syndicalism during the First World War 37 Part 2: Anarcho-syndicalism 40 Chapter 5: The Revolutionary Years 41 Chapter 6: From Revolutionary Syndicalism to Anarcho-syndicalism 51 Chapter 7: The World Anarcho-Syndicalist Movement in the 1920’s and 1930’s 64 Chapter 8: Ideological-Theoretical Discussions in Anarcho-syndicalism in the 1920’s-1930’s 68 Part 3: The Spanish Revolution 83 Chapter 9: The Uprising of July 19th 1936 84 2 Chapter 10: Libertarian Communism or Anti-Fascist Unity? 87 Chapter 11: Under the Pressure of Circumstances 94 Chapter 12: The CNT Enters the Government 99 Chapter 13: The CNT in Government - Results and Lessons 108 Chapter 14: Notwithstanding “Circumstances” 111 Chapter 15: The Spanish Revolution and World Anarcho-syndicalism 122 Part 4: Decline and Possible Regeneration 125 Chapter 16: Anarcho-Syndicalism during the Second World War 126 Chapter 17: Anarcho-syndicalism After World War II 130 Chapter 18: Anarcho-syndicalism in contemporary Russia 138 Bibliographic Essay 140 Acronyms 150 3 Translator’s introduction 4 In the first decade of the 21st century many labour unions and labour feder- ations worldwide celebrated their 100th anniversaries. This was an occasion for reflecting on the past century of working class history. Mainstream labour orga- nizations typically understand their own histories as never-ending struggles for better working conditions and a higher standard of living for their members –as the wresting of piecemeal concessions from capitalists and the State. -

Charlotte Wilson, the ''Woman Question'', and the Meanings of Anarchist Socialism in Late Victorian Radicalism

IRSH, Page 1 of 34. doi:10.1017/S0020859011000757 r 2011 Internationaal Instituut voor Sociale Geschiedenis Charlotte Wilson, the ‘‘Woman Question’’, and the Meanings of Anarchist Socialism in Late Victorian Radicalism S USAN H INELY Department of History, State University of New York at Stony Brook E-mail: [email protected] SUMMARY: Recent literature on radical movements in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries has re-cast this period as a key stage of contemporary globali- zation, one in which ideological formulations and radical alliances were fluid and did not fall neatly into the categories traditionally assigned by political history. The following analysis of Charlotte Wilson’s anarchist political ideas and activism in late Victorian Britain is an intervention in this new historiography that both supports the thesis of global ideological heterogeneity and supplements it by revealing the challenge to sexual hierarchy that coursed through many of these radical cross- currents. The unexpected alliances Wilson formed in pursuit of her understanding of anarchist socialism underscore the protean nature of radical politics but also show an over-arching consensus that united these disparate groups, a common vision of the socialist future in which the fundamental but oppositional values of self and society would merge. This consensus arguably allowed Wilson’s gendered definition of anarchism to adapt to new terms as she and other socialist women pursued their radical vision as activists in the pre-war women’s movement. INTRODUCTION London in the last decades of the nineteenth century was a global crossroads and political haven for a large number of radical activists and theorists, many of whom were identified with the anarchist school of socialist thought. -

Louise Michel

also published in the rebel lives series: Helen Keller, edited by John Davis Haydee Santamaria, edited by Betsy Maclean Albert Einstein, edited by Jim Green Sacco & Vanzetti, edited by John Davis forthcoming in the rebel lives series: Ho Chi Minh, edited by Alexandra Keeble Chris Hani, edited by Thenjiwe Mtintso rebe I lives, a fresh new series of inexpensive, accessible and provoca tive books unearthing the rebel histories of some familiar figures and introducing some lesser-known rebels rebel lives, selections of writings by and about remarkable women and men whose radicalism has been concealed or forgotten. Edited and introduced by activists and researchers around the world, the series presents stirring accounts of race, class and gender rebellion rebel lives does not seek to canonize its subjects as perfect political models, visionaries or martyrs, but to make available the ideas and stories of imperfect revolutionary human beings to a new generation of readers and aspiring rebels louise michel edited by Nic Maclellan l\1Ocean Press reb� Melbourne. New York www.oceanbooks.com.au Cover design by Sean Walsh and Meaghan Barbuto Copyright © 2004 Ocean Press All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photo copying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. ISBN 1-876175-76-1 Library of Congress Control No: 2004100834 First Printed in 2004 Published by Ocean Press Australia: GPO Box 3279, -

2015-08-06 *** ISBD LIJST *** Pagina 1 ______Monografie Ni Dieu Ni Maître : Anthologie De L'anarchisme / Daniel Guérin

________________________________________________________________________________ 2015-08-06 *** ISBD LIJST *** Pagina 1 ________________________________________________________________________________ monografie Ni Dieu ni Maître : anthologie de l'anarchisme / Daniel Guérin. - Paris : Maspero, 1973-1976 monografie Vol. 4: Dl.4: Makhno ; Cronstadt ; Les anarchistes russes en prison ; L'anarchisme dans la guerre d'Espagne / Daniel Guérin. - Paris : Maspero, 1973. - 196 p. monografie Vol. 3: Dl.3: Malatesta ; Emile Henry ; Les anarchistes français dans les syndicats ; Les collectivités espagnoles ; Voline / Daniel Guérin. - Paris : Maspero, 1976. - 157 p. monografie De Mechelse anarchisten (1893-1914) in het kader van de opkomst van het socialisme / Dirk Wouters. - [S.l.] : Dirk Wouters, 1981. - 144 p. meerdelige publicatie Hem Day - Marcel Dieu : een leven in dienst van het anarchisme en het pacifisme; een politieke biografie van de periode 1902-1940 / Raoul Van der Borght. - Brussel : Raoul Van der Borght, 1973. - 2 dl. (ongenummerd) Licentiaatsverhandeling VUB. - Met algemene bibliografie van Hem Day Bestaat uit 2 delen monografie De vervloekte staat : anarchisme in Frankrijk, Nederland en België 1890-1914 / Jan Moulaert. - Berchem : EPO, 1981. - 208 p. : ill. Archief Wouter Dambre monografie The floodgates of anarchy / Stuart Christie, Albert Meltzer. - London : Sphere books, 1972. - 160 p. monografie L' anarchisme : de la doctrine à l'action / Daniel Guerin. - Paris : Gallimard, 1965. - 192 p. - (Idées) Bibliotheek Maurice Vande Steen monografie Het sociaal-anarchisme / Alexander Berkman. - Amsterdam : Vereniging Anarchistische uitgeverij, 1935. - 292 p. : ill. monografie Anarchism and other essays / Emma Goldman ; introduction Richard Drinnon. - New York : Dover Public., [1969?]. - 271 p. monografie Leven in de anarchie / Luc Vanheerentals. - Leuven : Luc Vanheerentals, 1981. - 187 p. monografie Kunst en anarchie / met bijdragen van Wim Van Dooren, Machteld Bakker, Herbert Marcuse. -

Federico Urales Y La Revista Blanca En El Circuito Anarquista Transnacional Jaime D

Federico Urales y La Revista Blanca en el circuito anarquista transnacional Jaime D. Rodríguez Madrazo Máster en Historia Contemporánea MÁSTERES DE LA UAM 2018 - 2019 Facultad de Filosofía y Letras Federico Urales y La Revista Blanca en el circuito anarquista transnacional Jaime D. Rodríguez Madrazo Tutora: Pilar Díaz Sánchez Máster Interuniversitarsio en Historia Contemporánea UAM CURSO 2018-2019 Retrato de Juan Montseny, alias Federico Urales, Instituto Internacional de Historia Social de Ámsterdam, c. 1927. Portada de La Revista Blanca 1 de enero de 1925 1 Índice 1. Introducción ......................................................................................................................... 3 2. Estado de la cuestión y metodología: Historiografía e historia transnacional ............... 5 2.1. Objetivos y metodología ............................................................................................ 13 3. Anarquismo y primorriverismo: una historia entrecruzada ......................................... 15 3.1. El camino hacia la dictadura .................................................................................... 19 4. “Un triunvirato compuesto de padre, madre e hija” ..................................................... 28 4.1. El camino hacia el exilio ............................................................................................ 30 4.2. El exilio como periodo formativo ............................................................................. 32 4.3. El nacimiento de “Federico Urales” y -

Anarchism in Hungary: Theory, History, Legacies

CHSP HUNGARIAN STUDIES SERIES NO. 7 EDITORS Peter Pastor Ivan Sanders A Joint Publication with the Institute of Habsburg History, Budapest Anarchism in Hungary: Theory, History, Legacies András Bozóki and Miklós Sükösd Translated from the Hungarian by Alan Renwick Social Science Monographs, Boulder, Colorado Center for Hungarian Studies and Publications, Inc. Wayne, New Jersey Distributed by Columbia University Press, New York 2005 EAST EUROPEAN MONOGRAPHS NO. DCLXX Originally published as Az anarchizmus elmélete és magyarországi története © 1994 by András Bozóki and Miklós Sükösd © 2005 by András Bozóki and Miklós Sükösd © 2005 by the Center for Hungarian Studies and Publications, Inc. 47 Cecilia Drive, Wayne, New Jersey 07470–4649 E-mail: [email protected] This book is a joint publication with the Institute of Habsburg History, Budapest www.Habsburg.org.hu Library of Congress Control Number 2005930299 ISBN 9780880335683 Printed in the United States of America CONTENTS INTRODUCTION 1 PART ONE: ANARCHIST SOCIAL PHILOSOPHY 7 1. Types of Anarchism: an Analytical Framework 7 1.1. Individualism versus Collectivism 9 1.2. Moral versus Political Ways to Social Revolution 11 1.3. Religion versus Antireligion 12 1.4. Violence versus Nonviolence 13 1.5. Rationalism versus Romanticism 16 2. The Essential Features of Anarchism 19 2.1. Power: Social versus Political Order 19 2.2. From Anthropological Optimism to Revolution 21 2.3. Anarchy 22 2.4. Anarchist Mentality 24 3. Critiques of Anarchism 27 3.1. How Could Institutions of Just Rule Exist? 27 3.2. The Problem of Coercion 28 3.3. An Anarchist Economy? 30 3.4. How to Deal with Antisocial Behavior? 34 3.5. -

L'amérique Hospitalière

Zo d’Axa Ellis Island L’Amérique hospitalière vue de derrière Reportage sur la sélection imposée aux candidats à l’immi- gration sur l’île d’Ellis Island à New-York, 1902. Suivi d’Une Route et morceaux choisis d’ Ellis Island de Georges Perec 2 3 L’Amérique hospitalière vue de derrière - Zo d’Axa Première partie : L’Amérique hospitalière vue de derrière [Extrait de La Vie illustrée, août 1902.] Sur son îlot, torche en main, éclairant le monde, face au large, la statue de la Liberté ne peut pas regarder l’Amérique. Ce pays jeune en profite pour lui jouer des tours pas drôles. Les enfants de Jonathan s’amusent. Tandis que la dame en bronze tournait le dos, ils ont bâti sur une île, la plus voisine, une belle maison de détention ! Ce n’est pas que ce soit de bon goût ; mais c’est massif, confortable : briques rouges et pierres de taille, des tourelles, et, sur la toiture centrale, deux énormes boules de bronze, posées comme des presses-paperasses, deux boulets plaisamment offerts pour les pieds de la Liberté. Les Yankees sont gens d’humour — au moins s’ils le font exprès. Ce sont surtout gens d’affaires. Ils ont besoin d’émigrants ; ils les appellent ; mais ils les pèsent, les examinent, les trient et jettent le déchet à la mer. J’entends qu’ils rembarquent de force, après les avoir détenus, ceux qui ne valent pas 25 dollars… À New-York un homme vaut tant — valeur marchande, argent liquide, chèques en banque. Un tel vaut mille livres sterling ! Master Jakson, qui ne valait plus rien à la suite de fâcheuses faillites, s’est relevé d’un bon coup : il vaut maintenant cent nulle dollars. -

London's Anarchist Clubs, 1884–1914

Shortlisted 2016 History and Theory The Texture of Politics: London’s Anarchist Clubs, 1884 – 1914 Jonathan Moses, Royal Holloway University London Research Awards Shortlist | History and Theory This project presents a very focused, meticulously researched and very well presented study that used a good range of robust research techniques to draw conclusions that merges historiography, the social sciences and architectural production. 2016 Judging Panel 2 The Texture of Politics: London’s Anarchist Clubs, 1884–1914 The Texture of Politics: London’s Anarchist Clubs, 1884 – 1914 Jonathan Moses Royal Holloway University London This research explores the history of London’s anarchist clubs in the late-Victorian and Edwardian periods. It focuses on three prominent examples: the Autonomie Club, at 6 Windmill Street in Fitzrovia, the Berner Street International Working Men’s Club, at 40 Berner Street, in Whitechapel, and the Jubilee Street Club, at 165 Jubilee Street, also in Whitechapel. In particular it aims to recover the ‘architectural principles’ of the clubs, reconstructing their aesthetic choices and exploring their representations, attempting, where possible, to link these to their practical use, organisation, and political ideology. In order to make this case it draws from newspaper etchings, illustrations, reports in the anarchist and mainstream press, court statements, memoirs of key anarchists, letters, oral interviews, building act case files and building plans. It concludes that the clubs – all appropriated buildings subsequently restructured for new use – were marked by the attempt to present an exterior appearance of respectability, which belied an interior tendency towards dereliction and ‘deconstruc- tion’. Although it acknowledges the material constraints informing such a style, the paper argues, by way of comparison with other political clubs of its kind and the tracing of anarchist aesthetic influences, that this was not incidental. -

Italian Anarchists in London (1870-1914)

1 ITALIAN ANARCHISTS IN LONDON (1870-1914) Submitted for the Degree of PhD Pietro Dipaola Department of Politics Goldsmiths College University of London April 2004 2 Abstract This thesis is a study of the colony of Italian anarchists who found refuge in London in the years between the Paris Commune and the outbreak of the First World War. The first chapter is an introduction to the sources and to the main problems analysed. The second chapter reconstructs the settlement of the Italian anarchists in London and their relationship with the colony of Italian emigrants. Chapter three deals with the activities that the Italian anarchists organised in London, such as demonstrations, conferences, and meetings. It likewise examines the ideological differences that characterised the two main groups in which the anarchists were divided: organisationalists and anti-organisationalists. Italian authorities were extremely concerned about the danger represented by the anarchists. The fourth chapter of the thesis provides a detailed investigation of the surveillance of the anarchists that the Italian embassy and the Italian Minster of Interior organised in London by using spies and informers. At the same time, it describes the contradictory attitude held by British police forces toward political refugees. The following two chapters are dedicated to the analysis of the main instruments of propaganda used by the Italian anarchists: chapter five reviews the newspapers they published in those years, and chapter six reconstructs social and political activities that were organised in their clubs. Chapter seven examines the impact that the outbreak of First World Word had on the anarchist movement, particularly in dividing it between interventionists and anti- interventionists; a split that destroyed the network of international solidarity that had been hitherto the core of the experience of political exile. -

DESCEND DANS Lr RU

l ca • NE. MONTE PAS AU CIEL DESCEND DANS lR RU qu'il est juste de le faire mais en faisant 1 • EDITO partager le jugement au mouvement en géné j MAUVAISE HUMEUR ••• ! ral ••• A commencer par ceux là mêmes qu'ils ne font jamais un geste, le plus petit soit • Depuh sa création, le CPCA n'a pas Béné il, en notre faveur. Il n'est pas de notre ficié de la part du mouvement libertaî:r~ en propos de rappeler des faits ni, encore général, de trop de publicité en sa faveur. moins, de rapporter des ragots, mais nous Bref, les anars n'ont pas compris suffî:sem• savons que notre existence ne plait pas à ment (ou peut-être ne 1 'ont-ils pas accepté?) tout le monde! mais après tout, le CPCA est le rôle comme la place que ce dernier pouvai un pari! si le désintérêt ou le faible in tenir au sein du mouvement. · térêt persitaient à notre encontre, nous • Certes, la plupart des militants le con serions en tirer les conséquences! naisse et compte sur lui, pour la diffusion lfEll attendant, nous demandons à quelques uns un peu de patience et aux autres, no.us de leurs communiqués, de leurs initiatives 1 et autres activités ••• Pourtant, on ne peut leur offrons notre 30 N° ! que le constater, si l'écho de l'activité COURAGE ET ANARCHIE anarchiste, et cela sans exclusive ni cen sure est prise en charge par le oulletin, il est à sens unique! car finalement, très CENTRE DE PROPAGANDE ET DE CULTURE ANARCHISTE peu de journaux ou de militants lioertaires procèdent de la même manière pour nous aider B.P. -

Contents 35 123 152 255

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS NOTE: In the spelling of Russian names, I have adhered, by and large, to the transliteration system of the Library of Congress, CONTENTS without the soft sign and diacritical marks. Exceptions have been made (a) when other spellings have become more or less conventional (Peter Kropotkin, Leo Tolstoy, Alexander Herzen, Angelica Balabanoff, Trotsky, and Gorky), (b) in two cases ACKNOWLEDGMENTS v where the persons involved spent most of their careers in the West and themselves used a different spelling in the Latin script INTRODUCTION 3 (Alexander Schapiro and Boris Yelensky), and (c) in a few diminutive names (Fanya, Senya,Sanya). PART I: 1905 1. THE STORMY PETREL 9 2. THE TERRORISTS 35 3. THE SYNDICALISTS 72 4. ANARCHISM AND ANTI INTELLECTUALISM 91 PART II: 1917 5. THE SECOND STORM 123 6. THE OCTOBER INSURRECTION 152 7. THE ANARCHISTS AND THE BOLSHEVIK REGIME 171 8. THE DOWNFALL OF RUSSIAN ANARCHISM 204 EPILOGUE 234 CHRONOLOGY 255 ANNOTATED BIBLIOGRAPHY 259 INDEX 291 Vl VU INTRODUCTION Although the idea of a stateless society can be traced back to ancient times, anarchism as an organized movement of social protest is a comparatively recent phenomenon. Emerging in Europe during the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, it was, like liberalism and socialism, primarily a response to the quickening pace of political and economic centralization brought on by the industrial revolution. The anarchists shared with the liberals a common hostility to centralized government, and with the socialists they shared a deep hatred of