FREEDOM in the 50 STATES an Index of Personal and Economic Freedom

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

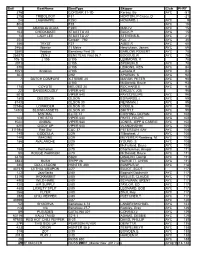

PHRF MASTER PHRF Master Nov 2017.Xlsx 2/15/18

Sail BoatName BoatType Skipper Club PHRF 276 CORSAIR 31-1D Kersey, Bo AYC -51 215 TRIBOLOGY F31 HORTON, P Casey, D -21 24 LAGNIAPPE F25C HOWARD,J AYC 9 80x F28 AYC 15 60 ARANA de AGUA F28R MAKI,V. AYC 15 163 CHECKMATE STILETTO 23 BUCK,P. AYC 15 1x LADY LEE STILETTO 27 STEVENS,R. AYC 21 22x Corsair 750 Kuc, J AYC 36 356 TRYST F27 AGEE,R AYC 60 246x Warrior 11 Metre Henrickson, James AYC 69 3580 Voodoo Beneteau First 35 BARLOW, ROBERT AYC 78 25527 ZEN 2 BENETEAU First 36.7 BOGGUS,W AYC 78 105-1 J 105 J/105 LEMMONS, K 78 307J J/105 SPURLIN,S AYC 78 675 J/105 LEMONS, KEN AYC 84 1051 Xcitation J/105 Lemons,K AYC 84 30J J/92 SPURLIN, S AYC 90 7 DUTCH COMFORT X-TREME 25 MARSH, PETER AYC 90 J/100 McDonald, Bruce AYC 93 178 COYOTE MELGES 24 ROCHARD,E. AYC 93 22 DANGEROUSLY VIPER 640 SIRCELY, JOE 96 601 VIPER 640 PAYET,FELIPE AYC 96 180 OBESSION OLSON EDWARDS,J. AYC 99 8143 OLSON 30 NEWMAN,J AYC 99 22586 LOWRIDER OLSON 30 COBB,G. AYC 99 149O BLOWN ASSETS OLSON 30 SMITH,T. AYC 99 MISTRAL ELITE 37 CUSHING, DORAN AYC 102 103 THE STIG VIPER 640 PAYET, FELIPE AYC 102 102x ANIMAL VIPER 640 JONES, JEFF & CARRIE AYC 102 42V GIDDY UP VIPER 640 VLANDINGHM AYC 105 31198x Red Sky C&C 37 PETERSON, BAY AYC 108 145 GODZILLA J/29 Tillinghast, J AYC 108 149 IMAGINE J/29 MEYERS,R Romberg, M. -

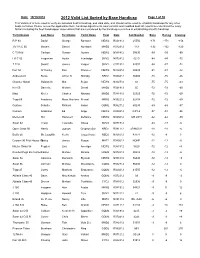

2012 Valid List Sorted by Base Handicap

Date: 10/19/2012 2012 Valid List Sorted by Base Handicap Page 1 of 30 This Valid List is to be used to verify an individual boat's handicap, and valid date, and should not be used to establish handicaps for any other boats not listed. Please review the appilication form, handicap adjustments, boat variants and modified boat list reports to understand the many factors including the fleet handicapper observations that are considered by the handicap committee in establishing a boat's handicap Yacht Design Last Name First Name Yacht Name Fleet Date Sail Number Base Racing Cruising R P 90 David George Rambler NEW2 R021912 25556 -171 -171 -156 J/V I R C 66 Meyers Daniel Numbers MHD2 R012912 119 -132 -132 -120 C T M 66 Carlson Gustav Aurora NEW2 N081412 50095 -99 -99 -90 I R C 52 Fragomen Austin Interlodge SMV2 N072412 5210 -84 -84 -72 T P 52 Swartz James Vesper SMV2 C071912 52007 -84 -87 -72 Farr 50 O' Hanley Ron Privateer NEW2 N072412 50009 -81 -81 -72 Andrews 68 Burke Arthur D Shindig NBD2 R060412 55655 -75 -75 -66 Chantier Naval Goldsmith Mat Sejaa NEW2 N042712 03 -75 -75 -63 Ker 55 Damelio Michael Denali MHD2 R031912 55 -72 -72 -60 Maxi Kiefer Charles Nirvana MHD2 R041812 32323 -72 -72 -60 Tripp 65 Academy Mass Maritime Prevail MRN2 N032212 62408 -72 -72 -60 Custom Schotte Richard Isobel GOM2 R062712 60295 -69 -69 -57 Custom Anderson Ed Angel NEW2 R020312 CAY-2 -57 -51 -36 Merlen 49 Hill Hammett Defiance NEW2 N020812 IVB 4915 -42 -42 -30 Swan 62 Tharp Twanette Glisse SMV2 N071912 -24 -18 -6 Open Class 50 Harris Joseph Gryphon Soloz NBD2 -

1989 Yearbook.Searchable.Pdf

~ ~_¢`-.=Y- ¢W@;~ ~ V/f, >sf>:¢~h~.%».,>;<,¢»£1¢q§,@-:¢»*&w"'f'/@f, ,~,,/_ ¢.-./~»-g-¢a'<-¢¢~f/»~1>.~# 2"*¢_- T§'2? "`_,_<`,_ < \._.\_ \ \ » ~ f;f,>;:~>z_<~ \ 75:1 ~#~ \ _ §___,>»»_\~f&,_< QQ* '\'»;K ' <=:~§ 1_- ~ :;:,~>_f ¢/ =»§~_~ _~_ .\_\ ~@y,_,@ _;~_ ,_ ,,,, _ , ,_ ._ ,_ ~ +;,~»w _"".---svnA . ~_;;_->»~S;;¢=_<___% _'2;; - -~Y _ ~» wf Q»»_¢~ ~»~~ *» -V;-f -w nf?-~f ~.w_,f__- -~,.__. , ._-_,m um _,W~~»f;_ f ~ 'V ~ T31 _ ::?'v ,J Q-mwa.-<»»» ¢~ þÿ3-°'> ¬'1 ' _,MM ~...,, ~, , M _ _WM%_,_ _ ~ ,, _#wap Z= _ f ~ 5`V" Fi? ,,__ _ ""' ff ~ 2 %?5Q<§ _ ' / _ W- = .,¢;.m~ __ 1 ._ ,__.M. §;fQ_5_A ;~W_&%_@____- ~ ~ §§ ;§1 ,, ~=_¢=_`»,_=,__AA2Q_ M- ,» -» ' ` ':' "1 T21 % Qra ii $5 El. A'i:"<"5 ~, '§ f <§' ROCHESTER @ /`¢>§§ ff " \/¢@=" __._, ____ __ Q _ef/> MQW Q {v»f>-;z 1° MMM1 T ~ W 1 ` ,_ 2 *v§_~Q»% ' __A xr 3 4 : ""/ ~ -5`\v;» _,qw ' ~>f~ * »"=* »i'?§'5"; _ ¢,- /` $2 M`\_ _QQ ~C"\`@ '" Q 1 Q § ~ 1 a$s§ ~°f'"1£@@»,. CLUB "\ -\\a~=;<»¢.~ _ $2 ' _ ~ _ / ~\_» ,_- ._ _ E§ ,\ '<:&i` Q ,-fm- 5 _ _r_ /i; '3'" _ """ ` ~ _ _ < _ 5_F ~, LW __ ____,;;§, _,_ _ , \ _§2 1989 ~ _;= % ~` :: ;; @zf'!, ,,-,M » _ L`v ; _@;v~>_~~ `ii?-@» __ __ _ ._ \-§. ~@. ,, _W -f mm T f ` z_ » ;'-H<»;§=» þÿ§ ¬¢ ""?"'»1'f3' ~ @ _ ._ ; ¢@;; _ ,_ , " *1*=*1?* _ ~~ . ;l _ ,W__,,_. -

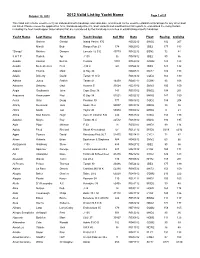

Valid List by Yacht Name Page 1 of 25

October 19, 2012 2012 Valid List by Yacht Name Page 1 of 25 This Valid List is to be used to verify an individual boat's handicap, and valid date, and should not be used to establish a handicaps for any other boat not listed. Please review the appilication form, handicap adjustments, boat variants and modified boat list reports to understand the many factors including the fleet handicapper observations that are considered by the handicap committee in establishing a boat's handicap Yacht Name Last Name First Name Yacht Design Sail Nbr Date Fleet Racing Cruising Gartner Gerald Island Packet 370 R052212 BWS2 192 207 Minelli Bob Ranger Fun 23 174 N062012 JBE2 177 183 "Sloopy" Melcher Dwayne Lacoste 42 S E 40779 R042212 BSN2 72 84 5 H T P Rudich Api J 105 96 R081812 JBE2 90 96 Acadia Keenan Burt H. Custom 1001 R062912 GOM2 123 123 Acadia Biebesheimer Fred J 34 C 69 R052412 JBE2 123 132 Adagio Thuma Mark O Day 30 N040512 MAT2 186 198 Adajio Doherty David Tartan 31 S D R061612 COD2 165 180 Adhara Jones Patrick Tartan 41 14459 R040212 GOM2 93 108 Advance Delaney Ged Avance 33 33524 R021312 SMV2 150 159 Aegis Gaythwaite John Cape Dory 36 141 R051012 BWS2 198 201 Aequoreal Rasmussen Paul O Day 34 51521 R032212 MRN2 147 159 Aerial Gray Doug Pearson 30 777 N061612 COD2 189 204 Affinity Desmond Jack Swan 48-2 50007 R042312 MRN2 33 36 Africa Smith Jud Taylor 45 50974 R030812 MHD2 9 21 Aftica Mac Kenzie Hugh Irwin 31 Citation S D 234 R061512 COD2 183 198 Agadou Mayne Roy Tartan 34 C 22512 R061812 MAN2 180 195 Agila Piper Michael E 33 18 R050912 MHD2 -

Who Have Shared Their Boats (267) and Their Sailing Expertise with Us Over the Years

THANKS SO MUCH TO THE SKIPPERS (222) WHO HAVE SHARED THEIR BOATS (267) AND THEIR SAILING EXPERTISE WITH US OVER THE YEARS. MANY HAVE SHARED MORE THAN ONE BOAT WITH SUS MEMBERS. WE SALUTE YOU!!!! WE THANK YOU!!!! First Name Last Name Boat Name Make Type Length Bob Akin Pegasus Hunter 30 sloop 30 Nick Allen [email protected] O'Day sloop 30 Steve Altman Shadowfax Pearson sloop 30 John Alton blueBlue thundreBThunder Tartan sloop 37 Cesar Ances Guanabara Catalina sloop 22 Len Ances Best Revenge sloop 27 Len Ances Esperance S2 sloop 27 Len Ances [email protected] O'Day sloop 20 Ken Anderson Starling sloop 27 Robert Anderson Enchantress Hatteras power 50 Elizabeth Anrig 21 Club O'Day sloop 22 Marc Appelbaum [email protected] Catalina Sloop 22 Barbara Bacci Mirque Sea Loch Ericson sloop 30 Jim Baltovich Freedom Mariner sloop 28 Sheryl Barnes Euphoria Catalina sloop 30 Chris Bayer [email protected] Navis Hunter 426 42 William J. Benton Sloopy sloop 22 Olga Berde Free Spirit Hunter cutter 37 Dennis Berry Arturus Nauticat Ketch 33 Luise Bianco Ms Liberty sloop 18 Ogden Bigelow, Jr. Topknits Island Gypsy Trawler 36 Andrew Blackman [email protected] Dufour Custom sloop 40 Roger Blaho New Moon Beneteau sloop 23 Roger Blaho [email protected] Magnolia C&C the 30 Richard Blanchard Cape Dory sloop 22 Steve Bleier Fo;Folly sloop 18 Steve Bleier Verboten sloop 27 Steve Bleier [email protected] Catalina sloop 34 Paul Blish [email protected] Cal sloop -

Centerboard Classes NAPY D-PN Wind HC

Centerboard Classes NAPY D-PN Wind HC For Handicap Range Code 0-1 2-3 4 5-9 14 (Int.) 14 85.3 86.9 85.4 84.2 84.1 29er 29 84.5 (85.8) 84.7 83.9 (78.9) 405 (Int.) 405 89.9 (89.2) 420 (Int. or Club) 420 97.6 103.4 100.0 95.0 90.8 470 (Int.) 470 86.3 91.4 88.4 85.0 82.1 49er (Int.) 49 68.2 69.6 505 (Int.) 505 79.8 82.1 80.9 79.6 78.0 A Scow A-SC 61.3 [63.2] 62.0 [56.0] Akroyd AKR 99.3 (97.7) 99.4 [102.8] Albacore (15') ALBA 90.3 94.5 92.5 88.7 85.8 Alpha ALPH 110.4 (105.5) 110.3 110.3 Alpha One ALPHO 89.5 90.3 90.0 [90.5] Alpha Pro ALPRO (97.3) (98.3) American 14.6 AM-146 96.1 96.5 American 16 AM-16 103.6 (110.2) 105.0 American 18 AM-18 [102.0] Apollo C/B (15'9") APOL 92.4 96.6 94.4 (90.0) (89.1) Aqua Finn AQFN 106.3 106.4 Arrow 15 ARO15 (96.7) (96.4) B14 B14 (81.0) (83.9) Bandit (Canadian) BNDT 98.2 (100.2) Bandit 15 BND15 97.9 100.7 98.8 96.7 [96.7] Bandit 17 BND17 (97.0) [101.6] (99.5) Banshee BNSH 93.7 95.9 94.5 92.5 [90.6] Barnegat 17 BG-17 100.3 100.9 Barnegat Bay Sneakbox B16F 110.6 110.5 [107.4] Barracuda BAR (102.0) (100.0) Beetle Cat (12'4", Cat Rig) BEE-C 120.6 (121.7) 119.5 118.8 Blue Jay BJ 108.6 110.1 109.5 107.2 (106.7) Bombardier 4.8 BOM4.8 94.9 [97.1] 96.1 Bonito BNTO 122.3 (128.5) (122.5) Boss w/spi BOS 74.5 75.1 Buccaneer 18' spi (SWN18) BCN 86.9 89.2 87.0 86.3 85.4 Butterfly BUT 108.3 110.1 109.4 106.9 106.7 Buzz BUZ 80.5 81.4 Byte BYTE 97.4 97.7 97.4 96.3 [95.3] Byte CII BYTE2 (91.4) [91.7] [91.6] [90.4] [89.6] C Scow C-SC 79.1 81.4 80.1 78.1 77.6 Canoe (Int.) I-CAN 79.1 [81.6] 79.4 (79.0) Canoe 4 Mtr 4-CAN 121.0 121.6 -

Ergebnisliste Zur 27. Steinhuder-Meer-Rund 2011

Ergebnisliste zur 27. Steinhuder-Meer-Rund 2011 Die Ergebnisliste ist auch im Internet unter www.steinhuder-meer-rund.de zu finden. Platz S-Nr. Bootstyp Steuermann Club Mannschaft Crew YZ ges.Zeit ber.Zeit sortiert nach berechneter Zeit 1 164 Start 6 Andersen,Jürgen SCMa Kempe,Julius H 116 02:48:16 02:25:03 2 181 Varianta Rosteck,Wolfgang SKM Hohmeyer-Rosteck,K. G 115 02:47:19 02:25:30 Rosteck,Jantje-Marie 3 118 Micro-Sail Marx,Francis SKM Brenscheidt,Björn H 114 02:45:58 02:25:35 Roszak,Jan 4 863 Neptun 22 Pesalla,Jörg BSV Schulz,Stefan H 118 02:51:57 02:25:43 5 96 Varianta 18 Antrecht,Alexander SCMa Langner,Monika G 114 02:46:15 02:25:50 Gensch,Alexander 6 57 Varianta Köhler,Lutz SKM Kropiwoda,Jörg H 115 02:47:50 02:25:57 Kropiwoda,Kai 7 1231 Neptun 22 Hodde,Christian SCL Bender,Christoph H 118 02:53:27 02:26:59 8 54 Micro-Proto Beselt,Dieter RSCZ Reiss,Wolfgang H 113 02:47:27 02:28:11 Maier,Jürgen 9 712 Varianta Busche, Dr.Jörg SKM Fichtel, Bernd G 115 02:50:33 02:28:18 Busche, Ann-Christin 10 783 Neptun 22 Pesalla,Marco YCvH Jackisch,Thomas H 118 02:55:32 02:28:45 11 1520 Neptun 22 Siekmann, Manfred SCL Bossen,Axel H 118 02:56:34 02:29:38 Langhorst,Alexander 12 433 Neptun 22 Altvater, Marianne SCL Blömker, Mona D 118 02:57:18 02:30:15 Früsmer, Doris 13 119 Varianta 18 Antrecht, Klaus SCMa Göing, Friederich H 114 02:52:47 02:31:34 14 234 Neptun 20 Götz,Helmut SCL Götz,Juliane G 121 03:03:56 02:32:01 Götz,Jutta 15 252 Varianta Roth,Michael SCMa Warnecke,Jörg H 117 02:58:24 02:32:29 16 127 Sportina 680 Meyer, Andreas SCLD Meyer, Bastian H 113 02:52:58 02:33:04 Meyer, Christian 17 1 Jantar 21 Schuster, Martin SCMa Schuster, Pauline G 111 02:51:10 02:34:12 Schuster, Josie 18 1117 Neptun 22 Skyrde,Wolfgang SKM Skyrde, Heike G 120 03:07:34 02:36:18 19 2004 Miglitsch 22 Petermann,Bernd SMW Petermann,Heiko H 120 03:08:43 02:37:16 Hundertmark,Werner Platz S-Nr. -

Yardstick Bodensee Februar 2018 Klasse Oder Namen Des

Yardstick Bodensee Februar 2018 Klasse oder Namen des Einzelbootes Eib TR Hk Segelmasse Typ YSZ Datum 1 Tonner Brava x 49/44/103 Kb 8621.09.2011 1 Tonner Bremen Eib x 44/42/93 Kb 9207.01.2015 1 Tonner High Noon x 36/49/115 Kb 9219.01.2012 1/2 Tonner Brigantia Eib x 26/25/61 Kb 97 07.01.2015 1/2 Tonner Gilardoni 915 15/31/65 Kb 107 28.04.2014 1/2 Tonner Ringelnatz Eib x 30/43/120 Kb 86 07.01.2015 1/4 Tonner Caipirina x 15/30/95 Kb 96 26.06.2011 1/4 Tonner Quadriga x 23/19/48 Kb 9612.08.2010 1/4 Tonner Saftiger Apfel 20 Eib x 22/16/37 Kb 101 07.01.2015 1/4-Tonner Tequilla x 11/20/45 Kb 110 11m OD 28/13/84 Kb 91 11m OD Top 28/41/86 Kb 86 11m Yacht Margaritta 7/8 x 33/34/90 Kb 91 11.04.2011 12 Fuss Dinghy 9,5/-/- Jol 12702.06.2015 12m OD 51/31/110 Kb 8128.06.2009 14 Footer 13/ 6/27 Jol 88 14 Fuss Dinghy 12/6/-- Jol 13403.01.2016 15 m2 SNS Classic 11/14/50 Kb 108 15 m2 SNS Modern 11/14/50 Kb 10414.01.2013 15er Jollenkreuzer Jkr 10019.01.2009 15er Jollenkreuzer Gaffel Tümmler x 11/09/28 Jkr 108 24.04.2012 15er Jollenkreuzer Judith Eib x 12/12/26 Jkr 105 10.01.2014 15er Jollenkreuzer Kniickspant Jkr 110 15er Jollenkreuzer Meteor x Jkr 10319.01.2009 15er Jollenkreuzer Zalou x 10/12/50 Jkr 109 19.01.2012 15er R Schärenkreuzer 11/13/32 Kb 101 09.01.2006 16er Jollenkreuzer Carpe Diem 09/08/32 Jol 112 27.11.2015 16er Jollenkreuzer Kneissel Jkr 10819.01.2012 18 Footer 24/-9/74 Jol 7611.01.2011 2 Tonner Carina x 35/75/160 Kb 93 2 Tonner Raring II x 26/53/120 Kb 98 2 Tonner Shamrock x 36/72/172 Kb 94 2.4m R 5/2,5/-- Kb 13029.04.2016 20 er Jollenkreuzer -

Good Old Boat Articles by Category

Good Old Boat articles by category Feature boats Cape Dory 30, Number 1, June 1998 Ericson 35, Number 2, Sept. 1998 Niagara 35, Number 3, Nov. 1998 Blackwatch 19, Number 4, Jan. 1999 Baba 30, Number 5, Mar. 1999 Pearson Commander/Ariel, Number 6, May 1999 Block Island 40, Number 7, July 1999 Nicholson 35, Number 8, Sept. 1999 Bayfield 40, Number 9, Nov. 1999 C&C Redwing 30, Number 10, Jan. 2000 Tanzer 22, Number 11, Mar. 2000 Morgan 38, Number 12, May 2000 Classic sailboats (Bermuda 40, Valiant 40, Cherubini 44), Number 12, May 2000 West Wight Potter, Number 13, July 2000 Allied Seabreeze, Number 14, Sept. 2000 Ericson 36C, Number 15, Nov. 2000 Seven Bells (part 1), Number 15, Nov. 2000 Seven Bells (part 2), Number 16, Jan. 2001 Catalina 22, Number 17, Mar. 2001 Cheoy Lee Offshore 40, Number 18, May 2001 Lord Nelson 35, Number 19, July 2001 Tartan 33, Number 20, Sept. 2001 Stone Horse, Number 22, Jan. 2002 Sea Sprite 34, Number 23, Mar. 2002 Sabre 30, Number 24, May 2002 Columbia 28, Number 25, July 2002 Cheoy Lee 35, Number 26, Sept. 2002 Nor'Sea 27, Number 27, Nov. 2002 Allied Seawind 30, Number 28, Jan. 2003 Bristol 24, Number 29, Mar. 2003 Montgomery 23, Number 30, May 2003 Victoria 18, Number 31, July 2003 Bristol 35.5 Number 32, September, 2003 Eastward Ho 31, Number 33, November, 2003 Ericson 29, Number 34, January 2004 Watkins 29, Number 36, May 2004 Spencer 35, Number 38, September 2004 Pacific Seacraft/Crealock 37, Number 39, November 2004 Cheoy Lee 32, Number 40, January 2005 Tayana 37, Number 41, March 2005 Bristol 29.9, Number 43, July 2005 Cape Dory 25, Number 45, November 2005 Lazy Jack 32, Number 46, January 2006 Alberg 30, Number 47, March 2006 Ranger 28, Number 50, September 2006 Allegra 24, Number 51, November 2006 Finisterre's sister, Number 52, January 2007 Islander 30, Number 53, March 2007 Review boats Albin Vega, Number 5, March 1999 Bristol Channel Cutter, Number 6, May 1999 Cal 20, Number 7, July 1999 Contessa 26, Number 8, Sept. -

Religious Freedom Institute

Religious Freedom: Why Now? Defending an Embattled Human Right The Witherspoon Institute Task Force on International Religious Freedom • Timothy Samuel Shah, principal author Matthew J. Franck, editor-in-chief Thomas F. Farr, chairman of the Task Force Princeton, New Jersey Copyright © 2012 by the Witherspoon Institute, Inc. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system now known or to be invented, without permission in writing from the publisher, except by a reviewer who wishes to quote brief passages in connection with a review written for inclusion in print, broadcast, or online media. Cover design by Barbara E. Williams Book design and layout by Margaret Trejo Printing by Thomson-Shore, Inc. Published in the United States by the Witherspoon Institute 16 Stockton Street, Princeton, New Jersey 08540 Library of Congress Control Number: 2012931788 ISBN 978-0-9814911-9-6 (softback) ISBN 978-0-9851087-0-0 (ebook) Printed in the United States of America Contents executive summary v introduction 1 Part One: The Ground of Religious Freedom chapter one What Is Religion? The Anthropological Basis of Religious Freedom 11 chapter two A Political Case for Religious Freedom 19 chapter three A Moral Case for Religious Freedom 26 chapter four A Religious Case for Religious Freedom 32 A Jewish Case for Religious Freedom by David Novak 37 A Christian Case for Religious Freedom by Nicholas -

YARDSTICK ZAHLEN 2017 19.12.2016 Seite 1

YARDSTICK ZAHLEN 2017 19.12.2016 Seite 1 Jollen 72 Moth Hydrofoil Mehrrumpfboote 74 18-Footer 94 Musto Performance Skiff 82 A-Cat 92 29er 118 Niedersachsenjolle 73 Brindl F35 66/85 114 420 114 O-Jolle 85 Dart 112 445 125 OD 11 88 Corsaire 750MkII 24.3/15.4/57.6 103 470 114 OK-Jolle 89 Dragonfly 800 sw 24/26/55 103 485-S-Rennjolle 173 Optimist 103 F24 Tri 21/11/50 83 49er 21.2 Gr.u.Ge./ 38 2Trapeze 110 Peter Gleiter 98 F27 Tri 26/23/76 98 505 118 Pfeil S 86 Hobbie 17 15.6/3.7 97 505 neu Segel und Spi 120 Pfeil-Jolle 113 Mauer Cat 114 Achatjolle 114 Phantom-Jolle 113 Milma Cat 117 Albatros 435 122 Phönix-Gaffeljolle 74 Nacra 60 B 118 Alezan 118 Pirat 76 Nacra F16 103 Aquila 110 Pirat Renn. 80 Prindle Cat 18 110 Byte CII 120 RA-Jolle 83 Sigma 9 Trimaran 9,6/50/115 117 Catalina Capri 14.2 118 Robby-Jolle 94 Topcat FI 116 Ciclone 108 RS-100 93 Topcat FII 116 Conger 103 RS-600 85 Topcat K 2 15.2/4 2 Trapeze 106 Contender 109 RS-Aero 80 Topcat K I 118 Delphin 11 m2 113 Schakel-Jolle 84 Topcat Spitfire III 120 Delphin 9,5 m2 94 Segelkanu 76 Tornado 125 Dinghy 12 ft 10.6 112 Siggerling 70 Tornad New 134 Dinghy 14 ft 110 Snipe 79 Ventilo 20 103 E-Jolle 110 Spanker 118 Europe 115 Spray-Jolle 112 Finn 120 Sprtotte 6 Yachten 103 Fireball 113 Tempo-Jolle 91 11 m One Design 102 Firebird 123 Vaurien 86 11 m One Design Top 112 Flibustier 120 VB-Jolle 108 15 qm SNS 10,4/13,4/50 bis1979 113 Flipper Scow 114 Wanderjolle 15 m2 104 15 qm SNS 10,4/13,4/50 ab 1980 125 Flying Bee 108 Wanderjolle 20 m2 108 35 qm Nat. -

UNITED STATES PERFORMANCE HANDICAP RACING FLEET LOW, HIGH, AVERAGE and MEDIAN PERFORMANCE HANDICAPS for the Years 2005 Through 2011 IMPORTANT NOTE

UNITED STATES PERFORMANCE HANDICAP RACING FLEET LOW, HIGH, AVERAGE AND MEDIAN PERFORMANCE HANDICAPS for the years 2005 through 2011 IMPORTANT NOTE The following pages lists base performance handicaps (BHCPs) and low, high, average, and median performance handicaps reported by US PHRF Fleets for well over 4100 boat classes or types displayed in Adobe Acrobat portable document file format. Use Adobe Acrobat’s ‘FIND” feature, <CTRL-F>, to display specific information in this list for each class. Class names conform to US PHRF designations. The information for this list was culled from data sources used to prepare the “History of US PHRF Affiliated Fleet Handicaps for 2011”. This reference book, published annually by the UNITED STATES SAILING ASSOCIATION, is often referred to as the “Red, White, & Blue book of PHRF Handicaps”. The publication lists base handicaps in seconds per mile by Class, number of actively handicapped boats by Fleet, date of last reported entry and other useful information collected over the years from more than 60 reporting PHRF Fleets throughout North America. The reference is divided into three sections, Introduction, Monohull Base Handicaps, and Multihull Base Handicaps. Assumptions underlying determination of PHRF Base Handicaps are explicitly listed in the Introduction section. The reference is available on-line to US SAILING member PHRF fleets and the US SAILING general membership. A current membership ID and password are required to login and obtain access at: http://offshore.ussailing.org/PHRF/2011_PHRF_Handicaps_Book.htm . Precautions: Reported handicaps base handicaps are for production boats only. One-off custom designs are not included. A base handicap does not include fleet adjustments for variances in the sail plan and other modifications to designed hull form and rig that determine the actual handicap used to score a race.