A Preliminary Archaeological Reconnaissance of Orile-Owu, Nigeria (Rev

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The World Bank Implementation Status & Results

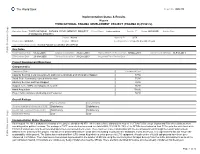

The World Bank Report No: ISR4370 Implementation Status & Results Nigeria THIRD NATIONAL FADAMA DEVELOPMENT PROJECT (FADAMA III) (P096572) Operation Name: THIRD NATIONAL FADAMA DEVELOPMENT PROJECT Project Stage: Implementation Seq.No: 7 Status: ARCHIVED Archive Date: (FADAMA III) (P096572) Country: Nigeria Approval FY: 2009 Product Line:IBRD/IDA Region: AFRICA Lending Instrument: Specific Investment Loan Implementing Agency(ies): National Fadama Coordination Office(NFCO) Key Dates Public Disclosure Copy Board Approval Date 01-Jul-2008 Original Closing Date 31-Dec-2013 Planned Mid Term Review Date 07-Nov-2011 Last Archived ISR Date 11-Feb-2011 Effectiveness Date 23-Mar-2009 Revised Closing Date 31-Dec-2013 Actual Mid Term Review Date Project Development Objectives Component(s) Component Name Component Cost Capacity Building, Local Government, and Communications and Information Support 87.50 Small-Scale Community-owned Infrastructure 75.00 Advisory Services and Input Support 39.50 Support to the ADPs and Adaptive Research 36.50 Asset Acquisition 150.00 Project Administration, Monitoring and Evaluation 58.80 Overall Ratings Previous Rating Current Rating Progress towards achievement of PDO Satisfactory Satisfactory Overall Implementation Progress (IP) Satisfactory Satisfactory Overall Risk Rating Low Low Implementation Status Overview As at August 19, 2011, disbursement status of the project stands at 46.87%. All the states have disbursed to most of the FCAs/FUGs except Jigawa and Edo where disbursement was delayed for political reasons. The savings in FUEF accounts has increased to a total ofN66,133,814.76. 75% of the SFCOs have federated their FCAs up to the state level while FCAs in 8 states have only been federated up to the Local Government levels. -

Violence in Nigeria's North West

Violence in Nigeria’s North West: Rolling Back the Mayhem Africa Report N°288 | 18 May 2020 Headquarters International Crisis Group Avenue Louise 235 • 1050 Brussels, Belgium Tel: +32 2 502 90 38 • Fax: +32 2 502 50 38 [email protected] Preventing War. Shaping Peace. Table of Contents Executive Summary ................................................................................................................... i I. Introduction ..................................................................................................................... 1 II. Community Conflicts, Criminal Gangs and Jihadists ...................................................... 5 A. Farmers and Vigilantes versus Herders and Bandits ................................................ 6 B. Criminal Violence ...................................................................................................... 9 C. Jihadist Violence ........................................................................................................ 11 III. Effects of Violence ............................................................................................................ 15 A. Humanitarian and Social Impact .............................................................................. 15 B. Economic Impact ....................................................................................................... 16 C. Impact on Overall National Security ......................................................................... 17 IV. ISWAP, the North West and -

Isbn: 978-978-57350-2-4

ASSESSMENT AND REPAIR OF SOLAR STREETLIGHTS IN TOWNSHIP AND RURAL COMMUNITIES (Kwara, Kogi, Osun, Oyo, Nassarawa and Ekiti States) A. S. OLADEJI B. F. SULE A. BALOGUN I. T. ADEDAYO B. N. LAWAL TECHNICAL REPORT NO. 11 ISBN: 978-978-57350-2-4 NATIONAL CENTRE FOR HYDROPOWER RESEARCH AND DEVELOPMENT ENERGY COMMISSION OF NIGERIA UNIVERSITY OF ILORIN, ILORIN, NIGERIA DECEMBER, 2013 i TABLE OF CONTENTS Table of Contents ii List of Figures iii List of Table iii 1.0 Introduction 2 1.1Background 2 1.2Objectives 4 2. 0Assessment of ECN 2008/2009 Rural Solar Streetlight Projects 5 2.1 Results of 2012 Re-assessment Exercise 5 2.1.1 Nasarawa State 5 2.1.1.1 Keffi 5 2.1.2 Kogi State 5 2.1.2.1 Banda 5 2.1.2.2 Kotonkarfi 5 2.1.2.3 Anyigba 5 2.1.2.4 Dekina 6 2.1.2.5 Egume 6 2.1.2.6 Acharu/Ogbogodo/Itama/Elubi 6 2.1.2.7 Abejukolo-Ife/Iyale/Oganenigu 6 2.1.2.8 Inye/Ofuigo/Enabo 6 2.1.2.9 Ankpa 6 2.1.2.10 Okenne 7 2.1.2.11 Ogaminana/Ihima 7 2.1.2.12 Kabba 7 2.1.2.13 Isanlu/Egbe 7 2.1.2.14 Okpatala-Ife / Dirisu / Obakume 7 2.1.2.15 Okpo / Imane 7 2.1.2.16 Gboloko / Odugbo / Mazum 8 2.1.2.17 Onyedega / Unale / Odeke 8 2.1.2.18 Ugwalawo /FGC / Umomi 8 2.1.2.19 Anpaya 8 2.1.2.20 Baugi 8 2.1.2.21 Mabenyi-Imane 9 ii 2.1.3 Oyo State 9 2.1.3.1 Gambari 9 2.1.3.2 Ajase 9 2.1.4 Kwara State 9 2.1.4.1Alaropo 9 2.1.5 Ekiti State 9 2.1.5.1 Iludun-Ekiti 9 2.1.5.2 Emure-Ekiti 9 2.1.5.3 Imesi-Ekiti 10 2.1.6 Osun State 10 2.1.6.1 Ile-Ife 10 2.1.6.3 Oke Obada 10 2.1.6.4 Ijebu-Jesa / Ere-Jesa 11 2.2 Summary Report of 2012 Re-Assessment Exercise, Recommendations and Cost for the Repair 11 2.3 Results of 2013 Re-assessment Exercise 27 2.2.1 Results of the Re-assessment Exercise 27 2.3.1.1 Results of Reassessment Exercise at Emir‟s Palace Ilorin, Kwara State 27 2.3.1.2 Results of Re-assessment Exercise at Gambari, Ogbomoso 28 2.3.1.3 Results of Re-assessment Exercise at Inisha 1&2, Osun State 30 3.0 Repairs Works 32 3.1 Introduction 32 3.2 Gambari, Surulere, Local Government, Ogbomoso 33 3.3 Inisha 2, Osun State 34 4. -

Women of Owu, and for Love of Biafra

i IHEK WEME, CHIKERENWA KINGSLEY PG/M.A/11/61263 WAR AND TERRORISM IN CONTEMPORARY NIGERIAN DRAMA: A PSYCHOANALYTIC STUDY OF MADMEN AND SPECIALISTS, WOMEN OF OWU, AND FOR LOVE OF BIAFRA DEPARTMENT OF THEATRE AND FILM STUDIES FACULTY OF ARTS Digitally Signed by: Content manager’s Name DN : CN = Webmaster’s name Ameh Joseph Jnr O= University of Nigeria, Nsukka OU = Innovation Centre ii TITLE PAGE WAR AND TERRORISM IN CONTEMPORARY NIGERIAN DRAMA: A PSYCHOANALYTIC STUDY OF MADMEN AND SPECIALISTS , WOMEN OF OWU , AND FOR LOVE OF BIAFRA BY IHEKWEME, CHIKERENWA KINGSLEY PG/M.A/11/61263 DEPARTMENT OF THEATRE AND FILM STUDIES UNIVERSITY OF NIGERIA, NSUKKA JUNE, 2013 CERTIFICATION iii This is to certify that IHEKWEME, Chikerenwa Kingsley, a postgraduate student of Theatre and Film Studies with registration number PG/M.A/11/61263, has satisfactorily completed the research/project requirements for the award of the degree of Master of Arts (M.A) in the Department of Theatre and Film Studies, University of Nigeria, Nsukka. This project is original and has not been submitted in part or whole for any other degree of this or any other University. SUPERVISOR: Dr Uche- Chinemere Nwaozuzu Signature ___________________ Date ______________________ APPROVAL PAGE iv This project report by Ihekweme, Chikerenwa Kingsley PG/M.A/11/61263 has been approved by the Department of Theatre and Film Studies, University of Nigeria, Nsukka. BY _________________________ _____________________ Dr Uche Chinemere Nwaozuzu Prof. Emeka Nwabueze Supervisor Head of Department ____________________ External Examiner v DEDICATION To All victims and casualties of war and terror in Nigeria Especially those who still suffer mentally from their losses vi ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I appreciate the kindness and meticulousness of my lecturer and supervisor, Dr Uche- Chinemere Nwaozuzu for accepting to guide me. -

About the Contributors

ABOUT THE CONTRIBUTORS EDITORS MARINGE, Felix is Head of Research at the School of Education and Assistant Dean for Internationalization and Partnerships in the Faculty of Humanities, University of the Witwatersrand, South Africa. With Dr Emmanuel Ojo, he was host organizer of the Higher Education Research and Policy Network (HERPNET) 10th Regional Higher Education Conference on Sustainable Transformation and Higher Education held in South Africa in September 2015. Felix has the unique experience of working in higher education in three different countries, Zimbabwe; the United Kingdom and in South Africa. Over a thirty year period, Felix has published 60 articles in scholarly journals, written and co-edited 4 books, has 15 chapters in edited books and contributed to national and international research reports. Felix is a full professor of higher education at the School of Education, University of the Witwatersrand (WSoE) specialising in research around leadership, internationalisation and globalisation in higher education. OJO, Emmanuel is lecturer at the School of Education, University of the Witwatersrand, South Africa. He is actively involved in higher education research. His recent publication is a co-authored book chapter focusing on young faculty in South African higher education, titled, Challenges and Opportunities for New Faculty in South African Higher Education Young Faculty in the Twenty-First Century: International Perspectives (pp. 253-283) published by the State University of New York Press (SUNY). He is on the editorial board of two international journals: Journal of Higher Education in Africa (JHEA), a CODESRIA publication and Journal of Human Behaviour in the Social Environment, a Taylor & Francis publication. -

An Evaluation of the Implementation of Early Childhood Education Curriculum in Osun State

Journal of Education and Practice www.iiste.org ISSN 2222-1735 (Paper) ISSN 2222-288X (Online) Vol.6, No.4, 2015 An Evaluation of the Implementation of Early Childhood Education Curriculum in Osun State Okewole, Johnson Oludele Institute of Education,Obafemi Awolowo University,Ile-Ife, Osun State, Nigeria E-mail: [email protected] Iluezi-Ogbedu Veronica Abuovbo Department of Arts and Social Sciences,University of Lagos, Nigeria E-mail: [email protected] Osinowo Olufunke Abosede Department of Arts and Social Sciences,University of Lagos, Nigeria E-mail: [email protected] Abstract Early Childhood Education as a subject in primary schools in Nigeria was first noticed among the private primary schools in the 80’s while the public primary schools did not incorporate it in their curriculum in Nigeria. Of recent, some state governments in Nigeria have just adopted and organized early childhood education unit into their primary schools. As a result of this new development, the Nigerian Educational Research and Development Council (NERDC) developed a National Curriculum for E. C. E. which both public and private schools use to achieve the stated objectives of E.C.E. as contained in the National Policy on Education (2004) in Nigeria. It is based on this that this study carried out an evaluation of the implementation of the National Curriculum as prepared by NERDC by the primary schools in Osun State, Nigeria, vis a vis the quality of personnel on ground, the adequacy or otherwise of the teaching and learning facilities, comparison of the expected curriculum and the observed curriculum, and the constraints to its implementation. -

Analysis of Heavy Metals in Vegetables Sold in Ijebu-Igbo, Ijebu North Local Government, Ogun State, Nigeria

International Journal of Scientific & Engineering Research, Volume 6, Issue 11, November-2015 130 ISSN 2229-5518 Analysis of Heavy Metals in Vegetables Sold in Ijebu-Igbo, Ijebu North Local Government, Ogun State, Nigeria *ABIMBOLA ‘WUNMI. A1, AKINDELE SHERIFAT. T2, JOKOTAGBA OLORUNTOBI. A2, AGBOLADE OLUFEMI .M1, AND SAM-WOBO SAMMY.O3 1Plant science and Applied Zoology Department, Olabisi Onabanjo University, Ago-Iwoye, Ogun State. 2Science Laboratory Technology Department, Abraham Adesanya Polytechnic, Ijebu-Igbo, Ogun State. 3 Department of Biological Sciences, Federal University of Agriculture, Abeokuta, Nigeria Abstract - A preliminary market study was conducted to assess the level of certain heavy metal in selected vegetable sold in Obada market and Atikori market, harvested from three farm-lands located in Ayesan, Dagbolu and Osunbodepo in Ijebu North Local Area Government. The vegetables were bitter-leaf (Vernonia amygdalina), fluted pumpkin (Talfaria occidentalis), water-leaf (Talinum triangulare), and jute mallow (Corchorus olitorius). The samples were analysed for heavy metals (Cr, Mn, Ni, Co, Cu, Cd, Zn, Pb, and Fe) using Atomic Absorption Spectrophotometer (AAS, Perkin Elmer model 2130), in accordance with AOAC. The result obtained showed, Jute Mallow had highest value of Zinc with 111.23 and lowest value of Co with 3.50; fluted Pumpkin had highest value of Mn with 45.50 and lowest value in CO with 1.75; Water Leaf had Zn with highest value 186.75 and Cd has the lowest; Bitter Leaf had Zn with 90.50 and Cd with 1.50. Keywords - Farm, Heavy Metals, Site, spectrophotometer, Vegetables —————————— —————————— INTRODUCTION vegetables contamination with heavy metals Heavy metal contamination of vegetables cannot derives from factors such as the application of be under-estimated as these foodstuffs are fertilizers, sewage sludge or irrigation with important componentsIJSER of human diet. -

Africa Report

PROJECT ON BUSINESS AND POLITICS IN THE MUSLIM WORLD AFRICA REPORT Second Quarterly Report on Africa April to June 2008 Volume: 1 Reports for the period April to May 2008 Principal Investigator: Prof. Dr. Ijaz Shafi Gilani Contributors Abbas S Lamptey Snr Research Associate Reports on Sub-Saharan AFrica Abdirisak Ismail Research Assistant Reports on East Africa INTERNATIONAL ISLAMIC UNIVERSITY ISLAMABAD BUSINESS AND POLITICS IN THE MUSLIM WORLD AFRICA REPORT Second Quarterly Report on Asia April to June 2008 Reports for the period April to May 2008 Volume: 1 Department of Politics and International Relations International Islamic University Islamabad 2 BUSINESS AND POLITICS IN THE MUSLIM WORLD AFRICA REPORT Second Quarterly Report on Africa 2008 Table of contents Reports for the month of April Week-1 April 01, 2008 05 Week-2 April 08, 2008 63 Week-3 April 15, 2008 120 Week-4 April 22, 2008 185 Week-5 April 29, 2008 247 Reports for the month of May Week-1 May 06, 2008 305 Week-2 May 12, 2008 374 Week-3 May 20, 2008 442 Country profiles Sources 3 4 BUSINESS AND POLITICS IN THE MUSLIM WORLD Weekly Presentation: April 1, 2008 Sub-Saharan Africa Abbas S Lamptey Period: From March 23 to March 29 2008 1. CHINA -AFRICA RELATIONS WEST AFRICA Sierra Leone: Chinese May Evade Govt Ban On Logging: Concord Times (Freetown):28 March 2008. Liberia: Chinese Women Donate U.S. $36,000 Materials: The NEWS (Monrovia):28 March 2008. Africa: China/Africa Trade May Hit $100bn in 2010:This Day (Lagos):28 March 2008. -

Title the Minority Question in Ife Politics, 1946‒2014 Author

Title The Minority Question in Ife Politics, 1946‒2014 ADESOJI, Abimbola O.; HASSAN, Taofeek O.; Author(s) AROGUNDADE, Nurudeen O. Citation African Study Monographs (2017), 38(3): 147-171 Issue Date 2017-09 URL https://doi.org/10.14989/227071 Right Type Departmental Bulletin Paper Textversion publisher Kyoto University African Study Monographs, 38 (3): 147–171, September 2017 147 THE MINORITY QUESTION IN IFE POLITICS, 1946–2014 Abimbola O. ADESOJI, Taofeek O. HASSAN, Nurudeen O. AROGUNDADE Department of History, Obafemi Awolowo University ABSTRACT The minority problem has been a major issue of interest at both the micro and national levels. Aside from the acclaimed Yoruba homogeneity and the notion of Ile-Ife as the cradle of Yoruba civilization, relationships between Ife indigenes and other communities in Ife Division (now in Osun State, Nigeria) have generated issues due to, and influenced by, politi- cal representation. Where allegations of marginalization have not been leveled, accommoda- tion has been based on extraneous considerations, similar to the ways in which outright exclu- sion and/or extermination have been put forward. Not only have suspicion, feelings of outright rejection, and subtle antagonism characterized majority–minority relations in Ife Division/ Administrative Zone, they have also produced political-cum-administrative and territorial ad- justments. As a microcosm of the Nigerian state, whose major challenge since attaining politi- cal independence has been the harmonization of interests among the various ethnic groups in the country, the Ife situation presents a peculiar example of the myths and realities of majority domination and minority resistance/response, or even a supposed minority attempt at domina- tion. -

Agulu Road, Adazi Ani, Anambra State. ANAMBRA 2 AB Microfinance Bank Limited National No

LICENSED MICROFINANCE BANKS (MFBs) IN NIGERIA AS AT SEPTEMBER 30, 2018 S/N Name Category Address State Description 1 AACB Microfinance Bank Limited State Nnewi/ Agulu Road, Adazi Ani, Anambra State. ANAMBRA 2 AB Microfinance Bank Limited National No. 9 Oba Akran Avenue, Ikeja Lagos State. LAGOS 3 ABC Microfinance Bank Limited Unit Mission Road, Okada, Edo State EDO 4 Abestone Microfinance Bank Ltd Unit Commerce House, Beside Government House, Oke Igbein, Abeokuta, Ogun State OGUN 5 Abia State University Microfinance Bank Limited Unit Uturu, Isuikwuato LGA, Abia State ABIA 6 Abigi Microfinance Bank Limited Unit 28, Moborode Odofin Street, Ijebu Waterside, Ogun State OGUN 7 Above Only Microfinance Bank Ltd Unit Benson Idahosa University Campus, Ugbor GRA, Benin EDO Abubakar Tafawa Balewa University Microfinance Bank 8 Limited Unit Abubakar Tafawa Balewa University (ATBU), Yelwa Road, Bauchi BAUCHI 9 Abucoop Microfinance Bank Limited State Plot 251, Millenium Builder's Plaza, Hebert Macaulay Way, Central Business District, Garki, Abuja ABUJA 10 Accion Microfinance Bank Limited National 4th Floor, Elizade Plaza, 322A, Ikorodu Road, Beside LASU Mini Campus, Anthony, Lagos LAGOS 11 ACE Microfinance Bank Limited Unit 3, Daniel Aliyu Street, Kwali, Abuja ABUJA 12 Achina Microfinance Bank Limited Unit Achina Aguata LGA, Anambra State ANAMBRA 13 Active Point Microfinance Bank Limited State 18A Nkemba Street, Uyo, Akwa Ibom State AKWA IBOM 14 Ada Microfinance Bank Limited Unit Agwada Town, Kokona Local Govt. Area, Nasarawa State NASSARAWA 15 Adazi-Enu -

Structure Plan for Ikirun and Environs (2014 – 2033)

STRUCTURE PLAN FOR IKIRUN AND ENVIRONS (2014 – 2033) State of Osun Structure Plans Project NIGERIA SOKOTO i KATSINA BORNO JIGAWA Y OBE ZAMFARA Kano Maiduguri KANO KEBBI KADUNA B A UCHI Kaduna GOMBE NIGER ADAMAWA PLATEAU KWARA Abuja ABUJA CAPITAL TERRITORYNASSARAWA O Y O T ARABA EKITI Oshogbo K OGI OSUN BENUE ONDO OGUN A ENUGU EDO N L LAGOS A a M g o B s R EBONY A ha nits CROSS O IMO DELTA ABIA RIVERS Aba RIVERS AKWA BAYELSA IBOM STRUCTURE PLAN FOR IKIRUN AND ENVIRONS (2014 – 2033) State of Osun Structure Plans Project MINISTRY OF LANDS, PHYSICAL PLANNING AND URBAN DEVELOPMENT Copyright © United Nations Human Settlements Programme (UN-HABITAT), 2014 All rights reserved United Nations Human Settlements Programme publications can be obtained from UN-HABITAT Regional and Information Offices or directly from: P.O. Box 30030, GPO 00100 Nairobi, Kenya. Fax: + (254 20) 762 4266/7 E-mail: [email protected] Website: http://www.unhabitat.org HS Number: HS/050/15E ISBN Number(Series): 978-92-1-133396-1 ISBN Number:(Volume) 978-92-1-132669-7 Disclaimer The designation employed and the presentation of the material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Secretariat of the United Nations concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area, or of its authorities, or concerning delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries, or regarding its economic system or degree of development. The analysis, conclusions and recommendations of the report do not necessarily reflect the views of the United Nations Human Settlements Programme (UN- HABITAT), the Governing Council of UN-HABITAT or its Member States. -

Download This Report

This Document is important and should be read carefully. If you are in any doubt about its contents or the action to take, please consult your stock broker, accountant, solicitor or any other professional adviser for guidance immediately. For information concerning certain risk factors which should be considered by prospective investor, see “Risk Factors” on page 21 - 22. OMOLUABI SAVINGS AND LOANS PLC RC 217889 Offer for Subscription Of 3,000,000,000 Ordinary Shares of50 Kobo Each At N0.55per share Payable in full on Application APPLICATION LIST OPENS: Wednesday, August XX, 2013 APPLICATION LIST CLOSES: Wednesday, September XX, 2013 ISSUING HOUSE/FINANCIAL ADVISER MorganCapital Securities Ltd.RC 306609 THIS PROSPECTUS AND THE SECURITIES WHICH IT OFFERS HAVE BEEN APPROVED AND REGISTERED BY THE SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSSION. THE INVESTMENTS AND SECURITIES ACT 2007 PROVIDES FOR CIVIL AND CRIMINAL LIABILITIES FOR THE ISSUE OF A PROSPECTUS WHICH CONTAINS A MISLEADING OR FALSE INFORMATION. REGISTRATION OF THIS PROSPECTUS AND THE SECURITIES WHICH IT OFFERS DOES NOT RELIEVE THE PARTIES OF ANY LIABILITY ARISING UNDER THE ACT FOR FALSE OR MISLEADING STATEMENTS CONTAINED OR FOR ANY OMISSION OF A MATERIAL FACT IN THE PROSPECTUS. THE REGISTRATION OF THIS PROSPECTUS DOES NOT IN ANY WAY WHATSOEVER SUGGEST THAT THE SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION ENDORSES OR RECOMMENDS THE SECURITIES OR ACCEPT RESPONSIBILITY FOR CORRECTNESS OF ANY STATEMENT MADE OR OPINION OR REPORT EXPRESSED THEREIN. EVERY PROSPECTIVE INVESTOR IS EXPECTED TO SCRUTINIZE THE INFORMATION CONTAINED IN THE PROSPECTUS INDEPENDENTLY AND EVALUATE THE SECURITIES WHICH IT OFFERS. THE DIRECTORS OF OMOLUABI SAVINGS AND LOANS PLC INDIVIDUALLY AND COLLECTIVELY ACCEPT RESPONSIBILITY FOR THE ACCURACY OF THE INFORMATION CONTAINED HEREIN.