Security and Displacement in Iraq Security and Sarah Kenyon Lischer Displacement in Iraq Responding to the Forced Migration Crisis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Echo Annual Review 2002

COMMISSIONER’S MESSAGE entire generations of uprooted people have only experienced war and exile. We have a duty to help Humanitarian them survive but the international community also needs to give more attention to finding durable long-term solutions. On the other hand, there were principles some positive developments during 2002 which suggest that even apparently intractable crises can be solved. I have already mentioned Angola. In Sri must be Lanka, the peace process also revealed major post- crisis needs but encouragingly, in a context where it was possible to identify the light at the end of the respected tunnel. In Afghanistan, where ECHO was still heavily engaged, the fact that so many people returned home was a good sign although a sustained international effort, especially on longer term re- construction, will be needed for some time before 1 we can say that this crisis is finally over. In the Balkans, the post-crisis consolidation continued, allowing ECHO to make further progress in phasing out its operations, in favour of longer term development instruments put in place by the European Union, as well as by other donors. In 2002, ECHO again paid close attention to “forgotten crises” with significant funding for people whose plight rarely hits the headlines, including Western Saharan, Burmese and Bhutanese refugees, and conflict victims in Nepal, Somalia and Northern François Goemans, ECHO Uganda. As the year drew to a close, and the first Poul Nielson visits a The Humanitarian Aid Office of the European disquieting signals started to appear, ECHO prepared hospital in the Commission (ECHO), which is one of the world’s for the possibility of a major new crisis in Iraq. -

Refugee Annual Report

Annual Report 2016–2017 Refugees buying charcoal from local host community members at Kakuma refugee camp, Kenya © RSC/N Omata Contents Director’s foreword 3 Our research 4 Policy and impact 12 Refugee economies in Kenya FEATURE ARTICLE 16 Studying and learning 18 Architectures of displacement FEATURE ARTICLE 24 Events 26 The politics of the Syrian refugee crisis FEATURE ARTICLE 30 The duties of refugees FEATURE ARTICLE 32 Outreach 34 Reflecting on 3 years as RSC Director FEATURE ARTICLE 39 Fundraising and development 40 Academic record 41 Income and expenditure 47 Staff and associates 48 Front cover photo: South Sudanese refugees till the earth for planting at Nyumanzi refugee settlement, Uganda Compiled by Tamsin Kelk Design and production by Oxford University Design Studio Cover photo credits © UNHCR/Jiro Ose 1 An engaging session at the 2017 Summer School with Matthew Gibney and Michelle Foster © RSC Refugee children play at a mask workshop, Schisto camp, Piraeus, Greece © UNHCR/Yorgos Kyvernitis © UNHCR/Yorgos 2 Director’s foreword The public focus on the European ‘refugee crisis’ has died down but rising populist nationalism has shaped the political landscape, threatening many governments’ commitments to support displaced populations. All this has occurred at a time when new crises have emerged around the world, from South Sudan to Yemen, and the United Nations is embarking on a process of reflection on whether and how to update the global governance of forced migration. Research has an important role to play: in challenging myths, reframing questions, providing critical distance, offering practical solutions, and upholding the value of evidence. -

Ockenden Part

OCKENDEN AND CAMBODIANS WHEN THE ORDINARY IS EXTRA-ORDINARY! These scenes were captured in Kong Kleng, a new community of former refugees and displaced people, including former fi ghting adversaries. It was a just an ordinary day – such a one that not long ago all of them could only dream about. Now everyday activities of growing rice, catching fi sh, and simple leisure are proof of the peace, social integration, and improved livelihoods of Cambodians in 2007. The scenes took place alongside a new road funded by Ockenden’s donor and partners, Sir Michael and Lady Kadoorie and the Kadoorie Charitable Foundation. 2 Design by nova: [email protected] VISION & DEDICATION The life of a refugee is far from ordinary. It does not matter International to depart from Cambodia but it did not mark where in the world they have been forced to abandon home, the end of its work. Instead they resolved to create an or for whatever reason, whether conflict or natural disaster, independent local successor organization. The handover their situation becomes extra-ordinary. Their very survival is and transition to “Ockenden-Cambodia” was completed by often at great risk. Invariably they all share just one simple 30 September 2007. Ockenden International Trustees, ambition - to return to a normal secure and healthy ordinary Management and Staff of many years can take pride and life as soon as possible. Many have extra-ordinary stories satisfaction in a job well done, in leaving behind a fi ne legacy, to tell, about their predicament, how they managed to live and a new civil society organisation with the facilities, through various crises, and how they overcame adversity. -

Teaming up for Success

. Real business . Real people . Real experience Teaming Up for Success Reward Advisory Services AFGHANISTAN: Remuneration Benchmarking Survey 2007 February 2007 A. F. Ferguson & Co. , A member firm of Chartered Accountants 2 AFGHANISTAN Remuneration Benchmarking Survey 2007 PwC would like to invite your organization to participate in the Remuneration Benchmarking Survey 2007 which will be conducted once every year. This survey will cover all multinational organizations and local companies in AFGHANISTAN, regardless of any particular industry/ sector. This effort is being formulated so as to bring organizations at par with other players in market-resulting by bringing sanity to management and HRM practice in Afghanistan especially during reconstruction era. The survey will comprise of two parts: • Part A – remuneration to personnel in managerial and executive cadres (excluding CEOs/ Country Heads) • Part B – remuneration to CEOs/ Country Heads (international and local nationals separately) • Part C – remuneration to non-management cadre Each report is prepared separately, and participants may choose to take part in either one or all three sections of the survey. Job benchmarking and data collection from the participating organizations will be done through personal visits by our consultants. A structured questionnaire will be used to record detailed information on salaries, allowances, all cash and non-cash benefits and other compensation policies. The collected information will be treated in strict confidence and the findings of the survey will be documented in the form of a report, which will be coded. Each participating organization will be provided a code number with which they can identify their own data and the report will only be available to the participant pool. -

Mission Statement

Mission statement UNHCR - The United Nations Refugee Agency UNHCR is mandated by the United Nations to lead and coordinate international action for the worldwide protection of refugees and the resolution of refugee problems. UNHCR’s primary purpose is to safeguard the rights and well-being of refugees. In its efforts to achieve this objective, UNHCR strives to ensure that everyone can exercise the right to seek asylum and find safe refuge in another state, and to return home voluntarily. By assisting refugees to return to their own country or to settle permanently in another country, UNHCR also seeks lasting solutions to their plight. UNHCR’s efforts are mandated by the organization’s Statute, and guided by the 1951 United Nations Convention relating to the Status of Refugees and its 1967 Protocol. International refugee law provides an essential framework of principles for UNHCR’s humanitarian activities. In support of its core activities on behalf of refugees, UNHCR’s Executive Committee and the UN General Assembly have authorized the organization’s involvement with other groups. These include former refugees who have returned to their homeland; internally displaced people; and people who are stateless or whose nationality is disputed. UNHCR seeks to reduce situations of forced displacement by encouraging states and other institutions to create conditions which are conducive to the protection of human rights and the peaceful resolution of disputes. In pursuit of the same objective, UNHCR actively seeks to consolidate the reintegration of returning refugees in their country of origin, thereby averting the recurrence of refugee-producing situations. UNHCR is an impartial organization, offering protection and assistance to refugees and others on the basis of their needs and irrespective of their race, religion, political opinion or gender. -

7155 Ockenden International, Formerly the Ockenden Venture, Refugee Charity of Woking: Records, Including Papers of Joyce Pearce Obe (1915-1985), Founder, 1929-2006

SURREY HISTORY SERVICE SURREY COUNTY COUNCIL 130 GOLDSWORTH ROAD, WOKING 7155 OCKENDEN INTERNATIONAL, FORMERLY THE OCKENDEN VENTURE, REFUGEE CHARITY OF WOKING: RECORDS, INCLUDING PAPERS OF JOYCE PEARCE OBE (1915-1985), FOUNDER, 1929-2006 Provenance Deposited by the Trustees of Ockenden International in January 2002, August 2002 and December 2006. The preparation of this catalogue was funded by the Heritage Lottery Fund in 2009-10. Introduction The Ockenden Venture was founded in 1951 by three local schoolteachers, and took its name from founder Joyce Pearce’s family home ‘Ockenden’ in White Rose Lane, Woking. The Ockenden Venture became a registered charity on 24 February 1955, under the War Charities Act 1940, its stated object being to receive young East European people from post World War II displaced persons camps in Germany and 'to provide for their maintenance, clothing, education, recreation, health and general welfare'. Within a few years, world events and the increasing numbers of refugees world wide would lead it to widen both its remit and its scope. The project had begun in 1951, when Joyce Pearce (1915- 1985) persuaded Woking District Council to help support a holiday for 17 displaced East European teenagers at her sixth form centre at Ockenden House, as part of the Festival of Britain. An ad hoc arrangement was subsequently made for two of the girls to stay in Woking when they had obtained visas to attend school in England. The plight of older non-German speaking children in the refugee camps, for whom the educational provision was inadequate, provided the stimulus for Joyce Pearce, her friend and teaching colleague Margaret Dixon (1907-2001) and her cousin Ruth Hicks (1900-1986), headmistress of Greenfield School, Woking, to found the Ockenden Venture. -

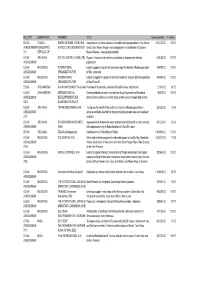

Contracts 2006

NO_CTRT BENEFICIARY PARTNER TITLE Amount granted % funding ECHO/- CONGO, UNITED NATIONS - FOOD AND Assistance to nutritional status of vulnerable returnee populations in the African 1.000.000,00 100,00 AF/BUD/2006/01 DEMOCRATIC AGRICULTURE ORGANIZATION Great Lakes Region through mass propagation and distribution of Cassava 001 REPUBLIC OF Mosaic Disease - free planting materials ECHO/- SRI LANKA ACTION CONTRE LA FAIM, (FR) Support in food security and living conditions to displacement affected 608.059,00 100,00 AS/BUD/2005/0 populations ECHO/- INDONESIA INTERNATIONAL Logistic support and public infrastructure repair for disaster affected population 449.997,00 100,00 AS/BUD/2005/0 ORGANIZATION FOR in Nias, Indonesia ECHO/- INDONESIA INTERNATIONAL Logistics support and public infrastructure repair for disaster affected population 495.945,00 100,00 AS/BUD/2005/0 ORGANIZATION FOR in Nias Phase IV ECHO/- AFGHANISTAN AGA KHAN FOUNDATION (United Provision of Shelters for Landslide Affected Families, Afghanistan 21.315,00 84,00 ECHO/- AFGHANISTAN MISSION D'AIDE AU Seeds distribution to most vulnerable families of Taywarah and Pasaband 96.627,00 100,00 AS/BUD/2005/0 DEVELOPPEMENT DES districts (Ghor province) currently facing another year of drought.Afghanistan 5024 ECONOMIES RURALES ECHO/- SRI LANKA TERRE DES HOMMES-CHE To improve the health of the conflict and tsunami affected populations in 320.333,00 20,06 AS/BUD/2005/0 Ampara and Batticaloa districts through providing durable water and sanitation 7001 solutions ECHO/- SRI LANKA FOLKEKIRKENS -

Skills Training for Youth Y

FMR 20 33 Skills training for youth by Barry Sesnan, Graham Wood, Marina L Anselme and Ann Avery RET/Hilde Lemey RET/Hilde Providing skills training for youth should be a key Ockenden International has Apprenticeship developed a system to help young training in component in promoting secure livelihoods for would-be entrepreneurs evaluate the refugee camps financial landscape, observe money in Bajaur agency, refugees. Young people must be given the chance to circulation and assess existing and Peshawar, potential markets. develop the practical, intellectual and social skills Pakistan that will serve them throughout their lives. Training must not reinforce traditional gender roles that impose oung people in conflict-torn No market demand, no restraints on livelihood opportunities. states – including genocide training It may be possible to develop more survivors in Rwanda, AIDS-rav- Y neutral training opportunities. The aged families in Uganda and ex-child There is often a conflict between the trades of carpenter, electrician and combatants in West Africa – have livelihood skills young people want to blacksmith are among those usually heavy responsibilities thrust upon learn, what they need to learn for sus- considered only appropriate for men them. Whilst they hope for a bright tainable future employment and what while mat making and weaving are future – a good job, a family, fulfill- is currently in demand in labour mar- more often regarded as women’s ment and respect – they often have to kets. Youth must tailor their activities. Agencies must consider put their own future on hold to sup- ambitions to market realities. One of the degree to which certain vocations port their families. -

From Refugee to Citizen: ‘Standing on My Own Two Feet’ a Research Report on Integration, ‘Britishness’ and Citizenship

From Refugee to Citizen: ‘Standing On My Own Two Feet’ A research report on integration, ‘Britishness’ and citizenship. Jill Rutter with Laurence Cooley, October 2007 From Refugee to Citzen:Sile Standing Reynolds on my own two and feet. Ruth Sheldon © Metropolitan Support Trust and the Institute of Public Policy Research 2007 From Refugee to Citzen: Standing on my own two feet. From Refugee to Citizen: ‘Standing On My Own Two Feet’ A research report on integration, ‘Britishness’ and citizenship. Contents Foreword i ippr iii Refugee Support iv About the authors v Acknowledgements vi Glossary and acronyms vii 1. Introduction 1 2. The last 50 years of refugee migration to the UK 11 3. Research methodology 29 4. Pre-arrival factors 41 5. Arrival 57 6. Institutional integration 81 7. Social interactions 99 8. Active citizens: political and community participation 119 9. Acculturation, identity and belonging 131 10. The Britishness debate 163 11. Conclusions and recommendations 179 Bibliography 188 Appendices From Refugee to Citzen: Standing on my own two feet. From Refugee to Citzen: Standing on my own two feet. Foreword Barbara Roche, Chair of Metropolitan Support Trust It is a great pleasure to introduce the first piece of research commissioned by our new Research and Consultancy Unit. It explores the experiences of refugees who have arrived over the last 50 years and their sense of Britishness. Fifty years ago, Refugee Support (at that time known as BCAR Homes) was established, and we wanted to tell the story of our service users and other refugees over that time. From Refugee to Citizen: Standing on my own two feet allows refugees to speak for themselves. -

Overseas Aid Committee Annual Report 2005-06

Overseas Aid Committee of the Council of Ministers Annual Report 2005 - 2006 External Relations Division Government Office, Bucks Road Douglas, Isle of Man IM1 3PN December 2006 Price: £5.30 GD 037/06 Price Band F Overseas Aid Committee of the Council of Ministers Woman farmer with her new goat. © Africa Now Annual Report 2005 - 2006 Contents Introduction 1 Development aid project reports by charity or individual Action Village India 2 Africa Now 3 AGROFOREP 4 Ashram International 5 BasicNeeds UK Trust 6 BookPower 7 British Red Cross 8 CAFOD 10 Care International UK 12 Children in Crisis 13 Christian Aid 14 CINI UK 16 Concern Universal 17 Concern Worldwide 18 Dhaka Ahsania Mission 20 Dr Naranchimeg Jamiyanjamts 21 Excellent Development 22 Farm Africa 23 Grace Third World Fund 24 Gwalior Children’s Hospital Charity 25 Habitat for Humanity 26 Hand of Hope 27 Harvest Help 28 HelpAge International 30 ICT (International Children’s Trust) 31 Ingwavuma Orphan Care 32 International Care and Relief (ICR) 33 International Childcare Trust 34 International Service 35 Jeevika (formerly India Development Group) 36 Karen Hilltribes Trust 37 1 Karuna Trust 38 Koru Hospital Fund 38 LEPRA 39 The Leprosy Mission 40 LINK Community Development 41 Manx Landmine Action Appeal 42 Manx – Romanian Projects Trust 43 Marie Stopes International 44 Medecins du Monde 45 Medical Aid for Palestinians 46 Merlin 47 Mission Aviation Fellowship (MAF) 48 Mullavitu Hospital 49 Namaste Children’s House 50 Ockenden International 51 Out of Afrika 53 Plan UK 56 Powerful Information -

Refugees' Right to Work and Access to Labor Markets

KNOMAD STUDY Refugees’ Right to Work and Access to Labor Markets – An Assessment Part II: Count ry Cases (Preliminary) Roger Zetter Héloïse Ruaudel September 2016 i The KNOMAD Working Paper and Study Series disseminates work in progress under the Global Knowledge Partnership on Migration and Development (KNOMAD). A global hub of knowledge and policy expertise on migration and development, KNOMAD aims to create and synthesize multidisciplinary knowledge and evidence; generate a menu of policy options for migration policy makers; and provide technical assistance and capacity building for pilot projects, evaluation of policies, and data collection. KNOMAD is supported by a multi-donor trust fund established by the World Bank. Germany’s Federal Ministry of Economic Cooperation and Development (BMZ), Sweden’s Ministry of Justice, Migration and Asylum Policy, and the Swiss Agency for Development and Cooperation (SDC) are the contributors to the trust fund. The views expressed in this study do not represent the views of the World Bank or the sponsoring organizations. All queries should be addressed to [email protected]. KNOMAD studies, working papers and a host of other resources on migration are available at www.KNOMAD.org. ii Refugees’ Right to Work and Access to Labor Markets – An Assessment* Roger Zetter and Héloïse Ruaudel† Abstract For refugees, the right to work is vital for reducing vulnerability, enhancing resilience, and securing dignity. Harnessing refugees’ skills can also benefit local economic activity and national development. But there are many obstacles. Based on a sample of 20 countries hosting 70 percent of the world’s refugees, this study investigates the role and impact of legal and normative provisions providing and protecting refugees’ right to work within the 1951 Refugee Convention as well as from the perspective of non- signatory states. -

RSC Annual Report 2019-2020

Annual Report 2019–2020 Burundian refugee and trainee brass artisan, Elijah, holds freshly cast brass jewellery at a workshop with Bawa Hope in Nairobi, Kenya © UNHCR / Will Swanson Syrian refugee Mouhamad plays with his daughter on the rooftop of their house in Barja, Lebanon. Their resettlement to Norway is currently suspended due to COVID-19 © UNHCR / Diego Ibarra Sànchez © UNHCR / Diego Ibarra © UNHCR/Santiago Escobar-Jaramillo Contents Director’s foreword 3 Our research 4 Refugee-led initiatives at the time of COVID-19 FEATURE ARTICLE 13 Policy and impact 14 Borders and colonial legacies: the refugee regime in the Global South FEATURE ARTICLE 17 A tribute to Gil Loescher FEATURE ARTICLE 18 Studying and learning 20 Practising what you preach: sustainable energy access research in refugee settings FEATURE ARTICLE 25 Alumni retrospectives 26 Food and forced migration FEATURE ARTICLE 28 The private sector and refugee economies FEATURE ARTICLE 30 ‘Stateless’ alternatives to humanitarianism FEATURE ARTICLE 32 Events 34 Outreach 36 Fundraising and development 40 Academic record 41 Income and expenditure 47 Staff and associates 48 Front cover photo: Syrian refugees at Za’atari camp in Jordan attend the first resumption of Friday prayers since the coronavirus pandemic closed the mosques Cover photo credits: © UNHCR Compiled by Tamsin Kelk Production by Oxford University Design Studio 1 Dame Marina Warner gives the Annual Harrell-Bond Lecture 2019 at St Anne’s College in October © RSC © Mark E Breeze / University of Oxford / University E Breeze © Mark Decorated home in Za’atari camp in Jordan, an extract from the documentary Shelter Without Shelter by Mark E Breeze and Tom Scott-Smith 2 Director’s foreword It will come as little surprise if I say that this year project, ‘Undoing Discriminatory Borders’, looking at the RSC has been profoundly shaped by the at the unequal distribution of migration opportunities.