Imagining Judith: an Examination of Judith’S Representation In

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lesser Feasts and Fasts 2018

Lesser Feasts and Fasts 2018 Conforming to General Convention 2018 1 Preface Christians have since ancient times honored men and women whose lives represent heroic commitment to Christ and who have borne witness to their faith even at the cost of their lives. Such witnesses, by the grace of God, live in every age. The criteria used in the selection of those to be commemorated in the Episcopal Church are set out below and represent a growing consensus among provinces of the Anglican Communion also engaged in enriching their calendars. What we celebrate in the lives of the saints is the presence of Christ expressing itself in and through particular lives lived in the midst of specific historical circumstances. In the saints we are not dealing primarily with absolutes of perfection but human lives, in all their diversity, open to the motions of the Holy Spirit. Many a holy life, when carefully examined, will reveal flaws or the bias of a particular moment in history or ecclesial perspective. It should encourage us to realize that the saints, like us, are first and foremost redeemed sinners in whom the risen Christ’s words to St. Paul come to fulfillment, “My grace is sufficient for you, for my power is made perfect in weakness.” The “lesser feasts” provide opportunities for optional observance. They are not intended to replace the fundamental celebration of Sunday and major Holy Days. As the Standing Liturgical Commission and the General Convention add or delete names from the calendar, successive editions of this volume will be published, each edition bearing in the title the date of the General Convention to which it is a response. -

E Renaissance Society of America Annual Meeting Program

e Renaissance Society of America Annual Meeting Program Philadelphia April 02 - 04, 2020 Table of Contents Links to Program Times and Sessions ursday at 6:00 pm RSA Awards Ceremony Friday at 6:00 pm CANCELLED: Josephine Waters Bennett Lecture Saturday at 6:30 pm RSA 2020 Philadelphia Closing Reception ursday at 11:00 am RSA Board of Directors Meeting ursday at 4:00 pm Cervantes Society of America Business Meeting and Society for Renaissance Studies (UK) Annual Lecture Annual Lecture Friday at 12:45 pm RSA Council Meeting Friday at 4:00 pm Margaret Mann Phillips Lecture Saturday at 2:00 pm e RSA High School Teaching Program Saturday at 4:00 pm American Cusanus Society Lecture Society for the Study of Early Modern Women and Gender Annual Lecture and Business Meeting Saturday at 5:30 pm Society for the Study of Early Modern Women and Gender Reception Saturday at 5:45 pm RSA Member Meeting ursday at 9:00 am (More an) irteen Ways of Looking at a Preacher: Netherlandish Printmaking Before Aux uatre Vents: Approaches to Early Modern Spanish Preaching Professionalism in the Graphic Arts, ca. 1500–50 CANCELLED: Barberiniana – Aspects of the Barberini New Perspectives on Italian Art I Reign (1623–44): A New Renaissance in Baroue Rome New Technologies and Renaissance Studies I: Trace I and Pattern CANCELLED: French Tragedy and the Wars of Pico, Machiavelli, and Ficino: Metaphysics, Ethics, and Religion eology CANCELLED: Impressed upon the Imagination: Reassessing Lucrezia Marinella's Oeuvre I Recreating Manuscript Cultures in the Age of Print Reconsidering -

St. Bernard of Clairvaux Catholic Church 1 St

St. Bernard of Clairvaux Catholic Church 1 St. Bernard Lane * Bella Vista, AR 72715 Office (479) 855-9069 Fax (479) 855-9067 www.bvstbernard.org [email protected] Mass Schedule Sunday 9:00a.m.. Mon-Tues-Thurs-Fri 8:30a.m. Wednesday 5:30p.m. Saturday (Sunday Vigil) 5:00p.m. Holy Day (Vigil) 7:00p.m. Holy Day 9:00a.m. Rosary: Sat & Sun.-8:20am, Mon.-Tue-Thur-Fri 8:00a.m. Wed-5pm Sat-4:20pm . Holy Day Vigil 6:20pm Holy Day-8:20am Parish Council Bob Hardy, Donna Hruska, Art Danz, Kim Barrett, Carl Long, Dale Thelen, Tim Auge, Ed Klaeser and Chuck Pribbernow Finance Council Charlie Teal - Chair, Reconciliation Schedule Bob Stewart, Bob Pierce, Tim Considine, Wednesday- 4:00p.m. - 5:00p.m. Please call the Parish Office if an Don Schmutz and John White appointment is needed. Parish Staff Baptisms Registered parishioners for at least six months. By appointment. Preparation Fr. Barnabas Maria-Susai, IMS - Pastor classes required. Al Genna Marie Nowak Deacon Director, Youth Education First Communion Russ Anzalone Deacon Al Genna Two years in a religious education class is required for the Sacrament Parish Manager R.C.I.A. of First Communion. Roxanne Birchfield Ann Kedrowski Finance Music Director Christina Laughlin Sam Roller Confirmation Administrative Assistant Praise Team Leader Two years enrolled and attending confirmation class is required for the Mary Powers Joe Moloney Sacrament of Confirmation. Office Assistant Maintenance Marriage Preparation must begin a minimum of six months before a proposed Twelfth Sunday of Ordinary Time wedding date whether in this church or any other. -

Our Grimston Rectors by Stephanie Hall © 2021

Our Grimston Rectors By Stephanie Hall © 2021 Contents Page Our Medieval Rectors ............................................................................................................................. 2 Rev Thomas Hare .................................................................................................................................... 5 Rev Nicholas Carr- died 1530 .................................................................................................................. 6 Rev Richard (or Edward) Rochester died in 1560 ................................................................................... 7 Rev Rochester , 1530 – 1560 ................................................................................................................... 8 Rev William Pordage (Porridge) - died 1585 .......................................................................................... 9 Reverend William Thorowgood , 1544 – 1625 ..................................................................................... 10 Reverend Thomas Thorowgood, 1588 -1669........................................................................................ 12 Rev John Brockett 1613-1664 ............................................................................................................... 14 Reverend Thomas Cremer 1635 - 1694 ................................................................................................ 16 Reverend John Cremer 1663 - 1743 .................................................................................................... -

Mysteries of Silence Anaphora Press Port Townsend, WA Anaphorapress.Com

Mysteries of Silence Anaphora Press Port Townsend, WA anaphorapress.com Address Correspondence to: Anaphora Press 3110 San Juan Ave. Port Townsend, WA 98368 [email protected] First Printing, 2007 All Rights Reserved Copyright 2007 by Christopher Lewis Graphic Design: Nina Noble ISBN: 978-0-9801241-1-1 Printed in the United States of America Mysteries of Silence CONTEnts Wisteria 1 Preparing the Manuscript of a Garden Journal 3 Songbird from the Seasons of Paradise 15 Three Drops of Silence 21 The Ancient Teachings of the Winter Silence 23 Pilgrim 31 Nobilissima Visione 33 The Midnight Sun 41 Dry Season in an Ancient Orchard 43 Daughter 49 Marathon 51 Les Larmes ne Rappelle Point a la Vie 53 Elegy in Autumn Mist 55 Mimesis 59 Harvest 61 Golden Gate Park 65 A New Sketch of the Hidden Season 67 The Palace of Fine Arts 69 Seven Days from Home 71 The Funeral of Father Thomas 73 Notes 75 Mysteries of Silence WistEria (At St. Michael’s Orthodox School, Santa Rosa, on grounds once owned by the horticulturist Luther Burbank) A tapestry of sky woven into your balconies. Graceful arms stretch the canopy in clustered blooms. Each is a bell announcing one of the hours. Under the veil of your perpetual incense, children learn to listen, sing and play... The mysterious gardener that planted and pruned you, trained your branches to embrace and overshadow these buildings… Flowering during the fast, how many years to grow this large and strong? Silent witness of the interior secret, whisper—what is in the seedpod? “The secret is this: when it falls safely cradled in its pod, the pea does not know it has separated from me. -

University of Paris Libraries: Sainte Genevieve Library E

Purdue University Purdue e-Pubs Libraries Research Publications 1-1-2001 University of Paris Libraries: Sainte Genevieve Library E. Stewart Saunders Purdue University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://docs.lib.purdue.edu/lib_research Saunders, E. Stewart, "University of Paris Libraries: Sainte Genevieve Library" (2001). Libraries Research Publications. Paper 24. http://docs.lib.purdue.edu/lib_research/24 This document has been made available through Purdue e-Pubs, a service of the Purdue University Libraries. Please contact [email protected] for additional information. Copyright 2001 From International Dictionary of Library Histories by David H. Stam. Reproduced by permission of Routledge/Taylor & Francis Group, LLC. BIBLIOTHEQUE SAINTE GENEVIEVE 10 Place du Panthéon 75005 Paris, France Web URL: http://Panoramix.univ-Paris1.Fr/bsg/indx.html Significant Dates ca 508: Church of Sainte Geneviève founded. 8th-11th cent.: Period in which library founded. 1619: Library defunct. 1624: Library refounded. 1790: Library nationalized by revolutionary government. 1839: The Sainte Geneviève, Mazarin, and Arsenal Libraries joined under common administration. 1930: Library attached to the University of Paris. 1972: Interuniversity library for all campuses of the University of Paris. Significant Collections The Sainte Geneviève holds around 3 million volumes. In the general collection there are 1,100,000 monographs, 12,800 serials, and 2,800 subscriptions. Special Collections houses 4,230 manuscripts, 1,450 incunabula, and 120,000 special editions. The Bibliothèque littéraire Jacques Doucet, housed in Special Collections, is a collection of avant garde French literature. A Nordic collection of 163,000 volumes is also housed separately. The manuscript collection is rich in illuminated manuscripts. -

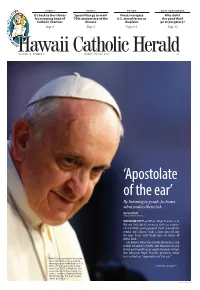

HAWAII HAWAII NATION QUESTION CORNER It’S Back to the Islands Special Liturgy to Mark Priests Navigate Why Didn’T for Incoming Head of 75Th Anniversary of the U.S

HAWAII HAWAII NATION QUESTION CORNER It’s back to the Islands Special liturgy to mark Priests navigate Why didn’t for incoming head of 75th anniversary of the U.S. armed forces as the good thief Catholic Charities diocese chaplains go to purgatory? Page 3 Page 5 Page 8-9 Page 12 HVOLUME 79,awaii NUMBER 14 CatholicFRIDAY, JULY 29, 2016 Herald$1 ‘Apostolate of the ear’ By listening to youth, he hears what makes them tick By Carol Glatz Catholic News Service VATICAN CITY — When Pope Francis is in Poland July 26-31 to meet with an expect- ed 2 million young people from around the world, he’s there with a firm idea of the dreams, fears and challenges so many of them face. He knows what lies inside the hearts and minds of today’s youth, not because of any third-party polling or sophisticated survey, but because Pope Francis practices what he’s called an “apostolate of the ear.” Pope Francis is pictured leaving an encounter with young people in the piazza outside the Basilica of St. Mary of the Angels in Assisi, Italy, Continued on page 10 in this Oct. 4, 2013, file photo. The pope plans to visit Assisi Aug. 4 to make a “simple and private” visit to the Portiuncola, the stone chapel rebuilt by St. Francis. CNS photo/Paul Haring 2 HAWAII HAWAII CATHOLIC HERALD • JULY 29, 2016 Official notices Hawaii Bishop’s calendar Bishop’s Schedule [Events indicated will be attended by Bishop’s Catholic delegate] Herald July 25-31, World Youth Day, Kraków, Poland. -

Winchester Cathedral Record 2020 Number 89

Winchester Cathedral Record 2020 Number 89 Friends of Winchester Cathedral 2 The Close, Winchester, Hampshire SO23 9LS 01962 857 245 [email protected] www.winchester-cathedral.org.uk Registered Charity No. 220218 Friends of Winchester Cathedral 2020 Royal Patron Her Majesty the Queen Patron The Right Reverend Tim Dakin, Bishop of Winchester President The Very Reverend Catherine Ogle, Dean of Winchester Ex Officio Vice-Presidents Nigel Atkinson Esq, HM Lord Lieutenant of Hampshire Cllr Patrick Cunningham, The Right Worshipful, the Mayor of Winchester Ms Jean Ritchie QC, Cathedral Council Chairman Honorary Vice-President Mo Hearn BOARD OF TRUSTEES Bruce Parker, Chairman Tom Watson, Vice-Chairman David Fellowes, Treasurer Jenny Hilton, Natalie Shaw Nigel Spicer, Cindy Wood Ex Officio Chapter Trustees The Very Reverend Catherine Ogle, Dean of Winchester The Reverend Canon Andy Trenier, Precentor and Sacrist STAFF Lucy Hutchin, Director Lesley Mead Leisl Porter Friends’ Prayer Most glorious Lord of life, Who gave to your disciples the precious name of friends: accept our thanks for this Cathedral Church, built and adorned to your glory and alive with prayer and grant that its company of Friends may so serve and honour you in this life that they come to enjoy the fullness of your promises within the eternal fellowship of your grace; and this we ask for your name’s sake. Amen. Welcome What we have all missed most during this dreadfully long pandemic is human contact with others. Our own organisation is what it says in the official title it was given in 1931, an Association of Friends. -

Violence, Christianity, and the Anglo-Saxon Charms Laurajan G

Eastern Illinois University The Keep Masters Theses Student Theses & Publications 1-1-2011 Violence, Christianity, And The Anglo-Saxon Charms Laurajan G. Gallardo Eastern Illinois University This research is a product of the graduate program in English at Eastern Illinois University. Find out more about the program. Recommended Citation Gallardo, Laurajan G., "Violence, Christianity, And The Anglo-Saxon Charms" (2011). Masters Theses. 293. http://thekeep.eiu.edu/theses/293 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Theses & Publications at The Keep. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses by an authorized administrator of The Keep. For more information, please contact [email protected]. *****US Copyright Notice***** No further reproduction or distribution of this copy is permitted by electronic transmission or any other means. The user should review the copyright notice on the following scanned image(s) contained in the original work from which this electronic copy was made. Section 108: United States Copyright Law The copyright law of the United States [Title 17, United States Code] governs the making of photocopies or other reproductions of copyrighted materials. Under certain conditions specified in the law, libraries and archives are authorized to furnish a photocopy or other reproduction. One of these specified conditions is that the reproduction is not to be used for any purpose other than private study, scholarship, or research. If a user makes a request for, or later uses, a photocopy or reproduction for purposes in excess of "fair use," that use may be liable for copyright infringement. This institution reserves the right to refuse to accept a copying order if, in its judgment, fulfillment of the order would involve violation of copyright law. -

Ecclesia & Synagoga

Ecclesia & Synagoga: then and now These images tell us something about the Today there is a move to redeem such images impact of art and image on our life of faith, to reflect the healing that has taken place in including our approach to Scripture. the relationship between Christians and Jews Depicted in these sculptures is the Church’s over the past fifty years since the Second journey out of its antisemitic past into a new Vatican Council’s declaration Nostra Aetate. era of respect and reconciliation with the The image above right shows a sculpture Jewish people. The two figures represent commissioned by St Joseph’s University, Ecclesia and Synagoga, church and Philadelphia.2 Here Synagoga and Ecclesia sit synagogue. Note the differences between the side by side, turned toward each other in artworks. friendship and as equal partners in a position The figures pictured above left are from the that suggests the chevruta method of Torah Cathedral in Strausbourg1 and are typical of study, one holding the Torah scroll, the other those which appeared repeatedly in church the Christian Bible. A miniature of this statue architecture and manuscripts of the Middle was presented to Pope Francis at the 2015 Ages. Lady Ecclesia is upright, regal, Annual Conference of the International victorious, holding a cross and the Christian Council of Christians and Jews held in Rome Scriptures. By contrast, Lady Synagoga is for the 50th Anniversary of Nostra Aetate. downcast, blindfolded, dishevelled, holding a Pope Francis himself blessed the original broken staff, the tablets of the Jewish Law artwork on his 2015 visit to the USA. -

The Movement for the Reformation of Manners, 1688-1715

THE MOVEMENT FOR THE REFORMATION OF MANNERS, 1688-1715 ANDREW GORDON CRAIG 1980 (reset and digitally formatted 2015) PREFACE TO THE 2015 VERSION This study was completed in the pre-digital era and since then has been relatively inaccessible to researchers. To help rectify that, the 1980 typescript submitted for the degree of PhD from Edinburgh University has been reset and formatted in Microsoft “Word” and Arial 12pt as an easily readable font and then converted to a read-only PDF file for circulation. It is now more compact than the original typescript version and fully searchable. Some minor typographical errors have been corrected but no material published post-1980 has been added except in the postscript (see below). Pagination in the present version does not correspond to the original because of computerised resetting of the text. Footnotes in this version are consecutive throughout, rather than chapter by chapter as required in the 1980 version. The original bound copy is lodged in Edinburgh University Library. A PDF scan of it is available at https://www.era.lib.ed.ac.uk /bitstream/handle/1842/6840/254333.pdf A further hand-corrected copy is available together with my research archive in the Special Collections Department at St Andrews University Library. http://www.st- andrews.ac.uk/library/specialcollections/ A note for researchers interested in the movement for the reformation of manners 1688-1715 and afterwards has been added as a postscript which lists other studies which have utilised this work and its sources in various ways. I am grateful to the Carnegie Trust for the Universities of Scotland for its generous scholarship support while a research student at Edinburgh University undertaking this study in the 1970s and to the following for their encouragement, guidance and support during the creation and completion of this research. -

22, 2017 Hawai'i Convention Center

2017 DAMIEN AND MARIANNE CATHOLIC CONFERENCE October 20 – 22, 2017 Hawai’i Convention Center CONFERENCE SCHEDULE Friday, October 20 Saturday, October 21 Sunday, October 22 Exhibit Hall Open Registration Check-in Registration Check-In 8:00am 7:00am 7:30am Registration Check-In Exhibit Hall Open Exhibit Hall Open Opening Ceremony 10:00am 8:30am Tongan Mass 8:30am Rosary Keynote Speaker 10:30am 10:00am Keynote Speaker 9:00am Keynote Speaker Lunch Break 12:15pm 11:15am Breakout Sessions 10:30am Performing Arts Play Exhibit Hall Open, Book Signing, 12:30pm 12:15pm Lunch Break 12:15pm Lunch Break Reconciliation Prayer Service – Divine Mercy Exhibit Hall Open, Book Signing, 3:00pm 12:30pm 1:00pm Closing Mass Chaplet Reconciliation Welcome from Bishop Larry Silva 1:45pm & 3:45pm Breakout Sessions Hawaiian Mass 3:00pm Dinner Break 5:00pm 4:00pm Dinner Break Exhibit Hall Open, Book Signing, Exhibit Hall Open, Book Signing, 5:00pm 4:00pm Reconciliation Reconciliation Keynote Speaker 7:00pm 7:15pm Breakout Sessions Youth Activities 8:00pm 8:30pm Concert Conference Sessions and Prayer Service Friday, October 20 10:00am 3:00pm – 5:00pm OPENING CEREMONY & SAINTS AWARD DIVINE MERCY CHAPLET Oli Prayer acknowledging Ke Akua, those who are present, and the In 1935, St. Faustina received a vision of an angel sent by God to reason for the gathering. chastise a certain city. She began to pray for mercy, but her prayers were powerless. Suddenly she saw the Holy Trinity and felt the 10:30am – 11:30am power of Jesus’ grace within her. At the same time she found P101 EXTRAORDINARY VISIONS! herself pleading with God for mercy with words she heard interiorly.