VOLUME : 12 Year : 2016 the JOURNAL of RASE a Peer Reviewed Journal of Studies in English

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

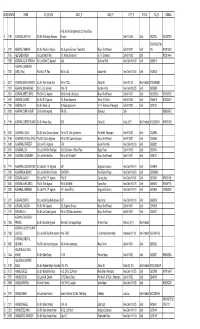

Complete List of Books in Library Acc No Author Title of Book Subject Publisher Year R.No

Complete List of Books in Library Acc No Author Title of book Subject Publisher Year R.No. 1 Satkari Mookerjee The Jaina Philosophy of PHIL Bharat Jaina Parisat 8/A1 Non-Absolutism 3 Swami Nikilananda Ramakrishna PER/BIO Rider & Co. 17/B2 4 Selwyn Gurney Champion Readings From World ECO `Watts & Co., London 14/B2 & Dorothy Short Religion 6 Bhupendra Datta Swami Vivekananda PER/BIO Nababharat Pub., 17/A3 Calcutta 7 H.D. Lewis The Principal Upanisads PHIL George Allen & Unwin 8/A1 14 Jawaherlal Nehru Buddhist Texts PHIL Bruno Cassirer 8/A1 15 Bhagwat Saran Women In Rgveda PHIL Nada Kishore & Bros., 8/A1 Benares. 15 Bhagwat Saran Upadhya Women in Rgveda LIT 9/B1 16 A.P. Karmarkar The Religions of India PHIL Mira Publishing Lonavla 8/A1 House 17 Shri Krishna Menon Atma-Darshan PHIL Sri Vidya Samiti 8/A1 Atmananda 20 Henri de Lubac S.J. Aspects of Budhism PHIL sheed & ward 8/A1 21 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad Bhagabatam PHIL Dhirendra Nath Bose 8/A2 22 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad PHIL Oriental Pub. 8/A2 Bhagabatam VolI 23 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad PHIL Oriental Pub. 8/A2 Bhagabatam Vo.l III 24 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad Bhagabatam PHIL Oriental Pub. 8/A2 25 J.M. Sanyal The Shrimad PHIL Oriental Pub. 8/A2 Bhagabatam Vol.V 26 Mahadev Desai The Gospel of Selfless G/REL Navijvan Press 14/B2 Action 28 Shankar Shankar's Children Art FIC/NOV Yamuna Shankar 2/A2 Number Volume 28 29 Nil The Adyar Library Bulletin LIT The Adyar Library and 9/B2 Research Centre 30 Fraser & Edwards Life And Teaching of PER/BIO Christian Literature 17/A3 Tukaram Society for India 40 Monier Williams Hinduism PHIL Susil Gupta (India) Ltd. -

Of Contemporary India

OF CONTEMPORARY INDIA Catalogue Of The Papers of Prabhakar Machwe Plot # 2, Rajiv Gandhi Education City, P.O. Rai, Sonepat – 131029, Haryana (India) Dr. Prabhakar Machwe (1917-1991) Prolific writer, linguist and an authority on Indian literature, Dr. Prabhakar Machwe was born on 26 December 1917 at Gwalior, Madhya Pradesh, India. He graduated from Vikram University, Ujjain and obtained Masters in Philosophy, 1937, and English Literature, 1945, Agra University; Sahitya Ratna and Ph.D, Agra University, 1957. Dr. Machwe started his career as a lecturer in Madhav College, Ujjain, 1938-48. He worked as Literary Producer, All India Radio, Nagpur, Allahabad and New Delhi, 1948-54. He was closely associated with Sahitya Akademi from its inception in 1954 and served as Assistant Secretary, 1954-70, and Secretary, 1970-75. Dr. Machwe was Visiting Professor in Indian Studies Departments at the University of Wisconsin and the University of California on a Fulbright and Rockefeller grant (1959-1961); and later Officer on Special Duty (Language) in Union Public Service Commission, 1964-66. After retiring from Sahitya Akademi in 1975, Dr. Machwe was a visiting fellow at the Institute of Advanced Studies, Simla, 1976-77, and Director of Bharatiya Bhasha Parishad, Calcutta, 1979-85. He spent the last years of his life in Indore as Chief Editor of a Hindi daily, Choutha Sansar, 1988-91. Dr. Prabhakar Machwe travelled widely for lecture tours to Germany, Russia, Sri Lanka, Mauritius, Japan and Thailand. He organised national and international seminars on the occasion of the birth centenaries of Mahatma Gandhi, Rabindranath Tagore, and Sri Aurobindo between 1961 and 1972. -

List of Documentaries Produced by Sahitya Akademi

LIST OF DOCUMENTARIES PRODUCED BY SAHITYA AKADEMI S.No.AuthorDirected byDuration 1. Amrita Pritam (Punjabi) Basu Bhattacharya 60 minutes 2. Akhtar-ul-Iman (Urdu) Saeed Mirza 60 minutes 3. V.K. Gokak (Kannada) Prasanna 60 minutes 4. ThakazhiSivasankara Pillai (Malayalam) M.T. Vasudevan Nair 60 minutes 5. Gopala krishnaAdiga (Kannada) Girish Karnad 60 minutes 6. Vishnu Prabhakar (Hindi) Padma Sachdev 60 minutes 7. Balamani Amma (Malayalam) Madhusudanan 27 minutes 8. VindaKarandikar (Marathi) Nandan Kudhyadi 60 minutes 9. Annada Sankar Ray (Bengali) Budhadev Dasgupta 60 minutes 10. P.T. Narasimhachar (Kannada) Chandrasekhar Kambar 27 minutes 11. Baba Nagarjun (Hindi) Deepak Roy 27 minutes 12. Dharamvir Bharti (Hindi) Uday Prakash 27 minutes 13. D. Jayakanthan (Tamil) Sa. Kandasamy 27 minutes 14. Narayan Surve (Marathi) DilipChitre 27 minutes 15. BhishamSahni (Hindi) Nandan Kudhyadi 27 minutes 16. Subhash Mukhopadhyay (Bengali) Raja Sen 27 minutes 17. TarashankarBandhopadhyay(Bengali)Amiya Chattopadhyay 27 minutes 18. VijaydanDetha (Rajasthani) Uday Prakash 27 minutes 19. NavakantaBarua (Assamese) Gautam Bora 27 minutes 20. Mulk Raj Anand (English) Suresh Kohli 27 minutes 21. Gopal Chhotray (Oriya) Jugal Debata 27 minutes 22. QurratulainHyder (Urdu) Mazhar Q. Kamran 27 minutes 23. U.R. Anantha Murthy (Kannada) Krishna Masadi 27 minutes 24. V.M. Basheer (Malayalam) M.A. Rahman 27 minutes 25. Rajendra Shah (Gujarati) Paresh Naik 27 minutes 26. Ale Ahmed Suroor (Urdu) Anwar Jamal 27 minutes 27. Trilochan Shastri (Hindi) Satya Prakash 27 minutes 28. Rehman Rahi (Kashmiri) M.K. Raina 27 minutes 29. Subramaniam Bharati (Tamil) Soudhamini 27 minutes 30. O.V. Vijayan (Malayalam) K.M. Madhusudhanan 27 minutes 31. Syed Abdul Malik (Assamese) Dara Ahmed 27 minutes 32. -

E-Newsletter

DELHI Bhasha Samman Presentation hasha Samman for 2012 were presidential address. Ampareen Lyngdoh, Bconferred upon Narayan Chandra Hon’ble Miniser, was the chief guest and Goswami and Hasu Yasnik for Classical Sylvanus Lamare, as the guest of honour. and Medieval Literature, Sondar Sing K Sreenivasarao in in his welcome Majaw for Khasi literature, Addanda C address stated that Sahitya Akademi is Cariappa and late Mandeera Jaya committed to literatures of officially Appanna for Kodava and Tabu Ram recognized languages has realized that Taid for Mising. the literary treasures outside these Akademi felt that while The Sahitya Akademi Bhasha languages are no less invaluable and no it was necessary to Samman Presentation Ceremony and less worthy of celebration. Hence Bhasha continue to encourage Awardees’ Meet were held on 13 May Samman award was instituted to honour writers and scholars in 2013 at the Soso Tham Auditorium, writers and scholars. Sahitya Akademi languages not formally Shillong wherein the Meghalaya Minister has already published quite a number recognised by the of Urban Affairs, Ampareen Lyngdoh of translations of classics from our Akademi, it therefore, was the chief guest. K Sreenivasarao, bhashas. instituted Bhasha Secretary, Sahitya Akademi delivered the He further said, besides the Samman in 1996 to welcome address. President of Sahitya conferment of sammans every year for be given to writers, Akademi, Vishwanath Prasad Tiwari scholars who have explored enduring scholars, editors, presented the Samman and delivered his significance of medieval literatures to lexicographers, collectors, performers or translators. This Samman include scholars who have done valuable contribution in the field of classical and medieval literature. -

Col Dir CW-2 DRAFT GAZETTE of INDIA

DRAFT GAZETTE OF INDIA (EXTRAORDINARY) PART I - SECTION 4 (ARMY BRANCH) B/43432/ID16/AG/CW-2 New Delhi, the 15 August 2016 No. 12(E) dated 15 August 2016. The President is pleased to award honorary rank of Naib Risaldar/Subedar to the under mentioned NCOs on the eve of Independence Day 2016 under Para 180 of the Regulation for the Army 1987, with effect from the dates shown against their names:- TO BE NAIB RISALDAR/SUBEDAR (ON RETIREMENT) 20 LANCERS 1 15461082K DFR DAVENDRA SINGH 01-07-2016 81 ARMOURED REGIMENT 2 15461025H DFR RAJENDRA PRASAD M 01-07-2016 90 ARMOURED REGIMENT 3 15461146K DFR HAR NARAYAN SHARMA 01-07-2016 47 ARMOURED REGIMENT 4 1099709Y DFR RAJENDRA KUMAR 01-05-2016 11 ARMOURED REGIMENT 5 1089687X DFR JAI PRAKASH PARIT 01-02-2016 13 ARMOURED REGIMENT 6 15461040X DFR PITAMBER 01-07-2016 50 ARMOURED REGIMENT 7 1099790W DFR HARMIT SINGH 01-05-2016 8 1099711W DFR RAJENDRA KUMAR 01-05-2016 9 1099602K DFR TEJBHAN PATEL 01-03-2016 ARMOURED CORPS 10 6483925L DFR AJIT RAM 01-07-2016 11 1099517F DFR BABU LAL 01-03-2016 12 1089680N DFR BHAWANI SINGH 01-02-2016 13 1089813Y DFR HARI PRAKASH 01-04-2016 14 1089968N DFR HARI PRASAD 01-07-2016 15 1581412X DFR JAFRUDDIN 01-08-2016 16 1089820P DFR JAGMANDER SINGH 01-04-2016 17 1099608L DFR KSHETRA MOHAN SING 01-03-2016 18 1099715M DFR LAKSHMAN RAM 01-05-2016 19 1581428H DFR LAL BAHADUR RAM 01-08-2016 Col Dir CW-2 1 20 15461178M DFR M BHAGWAN BHOSLE 01-08-2016 21 1089989K DFR MOHAMAD AMIN KHAN 01-08-2016 22 1089814F DFR MOHD SADEEQ 01-04-2016 23 6484234L DFR PHOOL SINGH 01-04-2016 24 6391683N -

Sahitya Akademi PUNJABI Publications

Sahitya Akademi PUNJABI Publications MONOGRAPHS (MAKERS OF INDIAN LITERATURE) Amrita Pritam (Punjabi writer) By Sutinder Singh Noor Pp. 96, Rs. 40 First Edition: 2010 ISBN 978-81-260-2757-6 Amritlal Nagar (Hindi writer) By Shrilal Shukla Translated by Narinder Bhullar Pp. 116, First Edition: 1996 ISBN 81-260-0088-0 Rs. 15 Baba Farid (Punjabi saint-poet) By Balwant Singh Anand Translated by Prem Kotia Pp. 88, Reprint: 1995 Rs. 15 Balwant Gargi (Punjabi Playright) By Rawail Singh Pp. 88, Rs. 50 First Edition: 2013 ISBN: 978-81-260-4170-1 Bankim Chandra Chatterji (Bengali novelist) By S.C. Sengupta Translated by S. Soze Pp. 80, First Edition: 1985 Rs. 15 Banabhatta (Sanskrit poet) By K. Krishnamoorthy Translated by Prem Kotia Pp. 96, First Edition: 1987 Rs. 15 Bhagwaticharan Verma (Hindi writer) By Shrilal Shukla Translated by Baldev Singh ‘Baddan’ Pp. 96, First Edition: 1992 ISBN 81-7201-379-5 Rs. 15 Bhai Kahn Singh Nabha (Punjabi scholar and lexicographer) By Paramjeet Verma Pp. 136, Rs. 50.00 First Edition: 2017 ISBN: 978-93-86771-56-8 Bhai Vir Singh (Punjabi poet) By Harbans Singh Translated by S.S. Narula Pp. 112, Rs. 15 Second Edition: 1995 Bharatendu Harishchandra (Hindi writer) By Madan Gopal Translated by Kuldeep Singh Pp. 56, Rs. 15 First Edition: 1984 Bharati (Tamil writer) By Prema Nand kumar Translated by Pravesh Sharma Pp. 103, Rs.50 First Edition: 2014 ISBN: 978-81-260-4291-3 Bhavabhuti (Sanskrit poet) By G.K. Bhat Translated by Prem Kotia Pp. 80, Rs. 15 First Edition: 1983 Chandidas (Bengali poet) By Sukumar Sen Translated by Nirupama Kaur Pp. -

Recent List of Additions January 2014

RECENT LIST OF ADDITIONS JANUARY 2014 COMPILED BY Sh. Kumar Sanjay, CLDO Smt. S. Wadhawan, ALIO Smt. Indira, SLIA PLANNING COMMISSION LIBRARY YOJANA BHAWAN NEW DELHI BIOGRAPHIES 1 Gandhi, Mohandas Karamchand Satya ke prayog: aatmkatha/ Mohandas Karmchand Gandhi.--Delhi: Arun Prakashan, 2012. 368p. ISBN: 8171460798. 923.254 G195S 151614 ** BIOGRAPHY-POLITICIANS 2 KPS Gill KPS Gill: the paramount cop / KPS Gill and Rahul Chandan. -- Noida: Maple Press, n.d. xii, 244p. ISBN: 9789350335604. 923.554 G475K 151819 ** BIOGRAPHY- POLICE OFFICERS 3 Yousafzai, Malala I am Malala: the girl who stood up for education and was shot by the Taliban / Malala Yousafzai.- London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 2013. 276p. ISBN: 9780297870920. 923.6581 Y82I 151820 ** BIOGRAPHY- SOCIAL REFORMERS 4 Biyani, Prakash The Boss / Prakash Biyani and Kamlesh Maheshwari. -- New Delhi: Prabhat Prakashan, 2013. 274p. ISBN: 9789350483060. 923.854 B625B 151528 ** BIOGRAPHY-BUSINESS LEADERS 5 Shirke, B G The crusade: autobiography of B G Shirke / B G Shirke.--3rd ed.-- Pune: Ameya Prakashan, 2009. 660p. ISBN: 8186172394. 926.2 S558C C16570 ** BIOGRAPGY-ENGINEERS 6 Singh, Khushwant Ek sau ek saal ka merathan runner: kahani toofani Fauja Singh ki / Khushwant Singh. -- New Delhi: Prabhat Prakashan, 2013. 135p. ISBN: 9789350482827. 927.964254 S617O 151529 ** BIOGRAPHY-RUNNERS 7 Singh, Milkha Bhag Milkha bhag / Milkha Singh and Sonia Swanlka. -- New Delhi: Prabhat Prakashan, 2013. 151p. ISBN: 9789350485118. 927.96420954 S617B 151562 ** BIOGRAPHY- RUNNERS ECONOMICS 8 Mishra, Mahendra Kumar Bharat ka aarthik itihaas / Mahendra Kumar Mishra. -- Delhi: Kalpana Prakashan, 2014. 320p. ISBN: 9788188790968. 330.954 M678B 151563 ** ECONOMICS-INDIA 9 Tyagi, Ruchi Shram arthshaastra / Ruchi Tyagi.-- Delhi: Aarya Publications, 2013. -

List of Shareholders- Uncl Fin Div 2012.Xlsx

SRNO FOLIO NAM1 SHARES NETDVD 1 G0006723 GANGA DEVI 476 1666.00 2 IN30023910741012 RAGHU NANDAN SAVARKUDELU 200 700.00 3 K0006892 KUNAL K MEHTA 400 1400.00 4 M0004121 MANISH BHAGAWANDAS 2048 7168.00 5 1201320000272633 VIJAY PRABHAKAR SHIRODKAR 20 70.00 6 1201070000038720 ANURAAG KUMAR SANGHI 4 14.00 7 IN30023911997807 SRIVATHSA K SIRA 400 1400.00 8 A0002227 ASHOK KUMAR GOEL 1120 3920.00 9 A0003073 ARVIND RASTOGI 44 154.00 10 D0002483 D K ROY 1280 4480.00 11 D0007394 DINESH VEDAVYAS KAMATH 196 686.00 12 A0007780 AJIT MAJHI 400 1400.00 13 B0001174 BODHAN RAO MARATHA 224 784.00 14 B0003624 BHAGWATIBEN PATEL 640 2240.00 15 B0102342 BHUPENDRAKUMAR N PANDYA 200 700.00 16 H0000715 HARISH CHANDAR 20 70.00 17 K0005252 KIRAN GIRDONIA 64 224.00 18 D0100131 DENESH CHANDRA MISHRA 576 2016.00 19 H0006718 H HARISHITA 400 1400.00 20 J0002639 JAGDISH ARORA 768 2688.00 21 H0001989 HANUMAN PRASAD GUPTA 44 154.00 22 J0100164 J J SARIN 1216 4256.00 23 J0002723 JAIKISHAN JAITHALIA 40 140.00 24 L0000247 LILADEVI NAINMAL 5 17.50 25 B0006389 BHARTI LAXMAN KHOTKAR 200 700.00 26 M0006209 MEENA HEMANT GANDHI 24 84.00 27 G0100086 GAYATRI SHUKLA 480 1680.00 28 R0005269 ROHAN PATEL 640 2240.00 29 P0004219 PADAM KUMAR CHAURASIA 1280 4480.00 30 N0003284 NARINDER GULATI 172 602.00 31 N0006121 NIRMAL KANTI RASTOGI 120 420.00 32 J0002457 JAI KISHAN JAITHALIA 192 672.00 33 R0006762 RAVI ARORA 16 56.00 34 S0009987 SANDEEP GUPTA 8 28.00 35 S0013008 SUDHAKAR SHETTY KADEKAR 400 1400.00 36 S0016630 SANJAY MANOHAR DIKSHIT 392 1372.00 37 M0006113 MANJULA JOSHI 320 1120.00 38 M0008775 -

Main Voter List 08.01.2018.Pdf

Sl.NO ADM.NO NAME SO_DO_WO ADD1_R ADD2_R CITY_R STATE TEL_R MOBILE 61-B, Abul Fazal Apartments 22, Vasundhara 1 1150 ACHARJEE,AMITAVA S/o Shri Sudhamay Acharjee Enclave Delhi-110 096 Delhi 22620723 9312282751 22752142,22794 2 0181 ADHYARU,YASHANK S/o Shri Pravin K. Adhyaru 295, Supreme Enclave, Tower No.3, Mayur Vihar Phase-I Delhi-110 091 Delhi 745 9810813583 3 0155 AELTEMESH REIN S/o Late Shri M. Rein 107, Natraj Apartments 67, I.P. Extension Delhi-110 092 Delhi 9810214464 4 1298 AGARWAL,ALOK KRISHNA S/o Late Shri K.C. Agarwal A-56, Gulmohar Park New Delhi-110 049 Delhi 26851313 AGARWAL,DARSHANA 5 1337 (MRS.) (Faizi) W/o Shri O.P. Faizi Flat No. 258, Kailash Hills New Delhi-110 065 Delhi 51621300 6 0317 AGARWAL,MAM CHANDRA S/o Shri Ram Sharan Das Flat No.1133, Sector-29, Noida-201 301 Uttar Pradesh 0120-2453952 7 1427 AGARWAL,MOHAN BABU S/o Dr. C.B. Agarwal H.No. 78, Sukhdev Vihar New Delhi-110 025 Delhi 26919586 8 1021 AGARWAL,NEETA (MRS.) W/o Shri K.C. Agarwal B-608, Anand Lok Society Mayur Vihar Phase-I Delhi-110 091 Delhi 9312059240 9810139122 9 0687 AGARWAL,RAJEEV S/o Shri R.C. Agarwal 244, Bharat Apartment Sector-13, Rohini Delhi-110 085 Delhi 27554674 9810028877 11 1400 AGARWAL,S.K. S/o Shri Kishan Lal 78, Kirpal Apartments 44, I.P. Extension, Patparganj Delhi-110 092 Delhi 22721132 12 0933 AGARWAL,SUNIL KUMAR S/o Murlidhar Agarwal WB-106, Shakarpur, Delhi 9868036752 13 1199 AGARWAL,SURESH KUMAR S/o Shri Narain Dass B-28, Sector-53 Noida, (UP) Uttar Pradesh0120-2583477 9818791243 15 0242 AGGARWAL,ARUN S/o Shri Uma Shankar Agarwal Flat No.26, Trilok Apartments Plot No.85, Patparganj Delhi-110 092 Delhi 22433988 16 0194 AGGARWAL,MRIDUL (MRS.) W/o Shri Rajesh Aggarwal Flat No.214, Supreme Enclave Mayur Vihar Phase-I, Delhi-110 091 Delhi 22795565 17 0484 AGGARWAL,PRADEEP S/o Late R.P. -

THE INDIAN JOURNAL of ENGLISH STUDIES an Annual Journal

ISSN-L 0537-1988 53 THE INDIAN JOURNAL OF ENGLISH STUDIES An Annual Journal VOL.LIII 2016 Editor-in-Chief Dr. Binod Mishra Associate Professor of English, IIT Roorkee The responsibility for facts stated, opinion expressed or conclusions reached and plagiarism, if any, in this Journal is entirely that of the author. The editor/publisher bears no responsibility for them whatsoever. THE OFFICIAL PUBLICATION OF ASSOCIATION FOR ENGLISH STUDIES OF INDIA 53 2016 INDIAN JOURNAL OF ENGLISH STUDIES Editor-in-Chief: Dr. Binod Mishra, CONTENTS Department of HSS, IIT Roorkee, Uttarakhand. The Indian Journal of English Studies (IJES), published since 1940, accepts Editorial Binod Mishra VII scholarly papers presented by members at the annual conferences World Literature in English of the Association for English Hari Mohan Prasad 1 Studies of India (AESI). Orders for the Indian and Western Canon copy of the journal for home, college, Charu Sheel Singh 12 departmental/university library may be sent to the Editor-in-Chief, Mahesh Dattani’s Ek Alag Mausam: Dr. Binod Mishra, by sending an Art for Life’s Sake Mukesh Ranjan Verma 23 e-mail on [email protected]. Teachers and research scholars are Encounters in the Human requested to place orders on behalf of Zoo through Albee their institutions for one or more J. S. Jha 33 copies. Orders can be sent to Dr. Binod John Dryden and the Restoration Milieu Mishra, Editor-in-Chief, IJES, 215/3 Vinod Kumar Singh 45 Saraswati Kunj, IIT Roorkee, District- Folklore and Film: Commemorating Haridwar, Uttarakhand-247667, Vijaydan Detha, the Shakespeare India. -

Summer Course Summer Course

SRI SATHYA SAI INSTITUTE OF HIGHER LEARNING (Deemed to be University) SUMMER COURSE in Indian Culture and Spirituality 2012 Summer Course in Indian Culture and Spirituality - 2012 Dedicated to our Beloved Master, Bhagawan Sri Sathya Sai Baba SRI SATHYA SAI INSTITUTE OF HIGHER LEARNING (Deemed to be University) SRI SATHYA SAI INSTITUTE OF HIGHER LEARNING (Deemed to be University) SUMMER COURSE in Indian Culture and Spirituality 8-10 June 2012 | Prasanthi Nilayam Copyright © 2012 by Sri Sathya Sai Institute of Higher Learning Vidyagiri, Prasanthi Nilayam – 515134, Anantapur District, Andhra Pradesh, India All Rights Reserved. The copyright and the rights of translation in any language are reserved by Sri Sathya Sai Institute of Higher Learning (Deemed to be University). No part, paragraph, passage, text, photograph or artwork of this book should be reproduced, transmitted or utilised - in original language or by translation - in any form or by means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or by any information, storage and retrieval system, except with prior permission, in writing from the Sri Sathya Sai Institute of Higher Learning, Vidyagiri, Prasanthi Nilayam - 515134, Anantapur District, Andhra Pradesh, India. First Edition: February 2013 Published by: Sri Sathya Sai Institute of Higher Learning www.sssihl.edu.in Printed at: Vagartha, # 149, 8th Cross, N R Colony, Bangalore – 560 019 +91 80 2242 7677 | [email protected] Preface The Sri Sathya Sai Institute of Higher Learning (SSSIHL) organized a Summer Course in Indian Culture and Spirituality from the 8th to 10th June 2012 at Prasanthi Nilayam, to mark the commencement of the new Academic Year. All the students and teachers of the Institute participated in this programme. -

S Public and Hantipur a Private Co and Its Neig Ollections Ghbourhoo Od

EAP643: Shantipur and its neighbourhood: Text and images of early modern Bengal in public and private collections Mr Abhijit Bhattacharya, Centre for Studies in Social Sciences, Calcutta 2013 award - Pilot project £9,300 for 8 months EAP643 has supplied an inventory of the collections surveyed which can be seen in the document below. Summary Page 2 Santipur Brahmo Samaj Collection Page 10 Krittibas Memorial Library Collection Page 75 Santipur Sahitya Parishad Collection Page 95 L M Sen Collection Page 327 Municipality Collection Page 355 Santipur Bangiya Purana Parisha Page 355 Further Information You can contact the EAP team at [email protected] 1 Summary Count "0" (not available in other holdings) OCLC BL SBS 288 351 KMLM 89 108 SSP 1398 1570 L. M. Sen Municipality Listing will be done only after digitisation. SBPP Listing will be done only after digitisation. Count "1" (available in other holdings) OCLC BL SBS 112 49 KMLM 29 10 SSP 237 65 L. M. Sen Municipality Listing will be done only after digitisation. SBPP Listing will be done only after digitisation. Sl. Subject in SSP No. Of No. Books 1 About Acharya Prafulla Chandra Roy and his institute. 1 2 About ancient bengali poets 1 3 About ancient bengali writers 1 4 About Buddha 1 2 5 About Indian Legend Women 1 6 About Library 1 7 About Textile 1 8 About Weavers 1 9 Aesthetics 1 10 Archeological 1 11 Arithmatic 1 12 Articles of Vidyasagar 1 13 Baby Care 1 14 Bengali Literature 1 15 Bengali text Book 1 16 Biography & Poems Collection 1 17 Biography of poets 1 18 Cattle Farming