Saira Wasim Interview

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Annual Report 2000

Mohtasib (Ombudsman)’s ANNUAL REPORT 2000 WAFAQI MOHTASIB (OMBUDSMAN)’S SECRETARIAT ISLAMABAD – PAKISTAN Tele: (92)-(51)-9201665–8, Fax: 9210487, Telex: 5593 WMS PK E-mail: [email protected] A Profile of the Ombudsman Mr. Justice Muhammad Bashir Jehangiri, the Senior Puisne Judge of the Supreme Court of Pakistan was administered oath of the Office of Acting Ombudsman of Pakistan by the President of the Islamic Republic of Paki- stan at Aiwan-e-Sadr (President’s House), Islamabad on 10th February, 2000. Mr. Justice Muhammad Bashir Jehangiri has rich experience in the legal profession and the judiciary, acquired over a period of about 38 years. His Lordship was born on 1st February, 1937 at Mansehra, NWFP. He received his school education in Lahore, obtaining distinctions and did B.A. (First-Class-First) from Abbottabad in 1960. He obtained his LL.B degree from the University Law College, Peshawar in 1962 and joined the Bar in February, 1963. After qualifying the West Pakistan P.C.S. (Judicial Branch) Exami- nation, he was appointed as Civil Judge on 7th March, 1966. After serving at various stations as Civil Judge and Senior Civil Judge, he was promoted as Additional District and Sessions Judge on 6th July, 1974 and as District and Sessions Judge on 24th October, 1974. His Lordship served as Judicial Commissioner, Northern Areas, from June, 1979 to December, 1982. He remained Special Judge, Customs, Taxation and Anti-smuggling (Central), Peshawar from March, 1983 to September, 1984. He took-over the charge as Joint Secretary, Ministry of Justice and Parliamentary Affairs (Justice Division), Islamabad on iii 12.9.1984. -

A New Paradigm for Pakistani Schools JUL 0 2 2003

Beyond the Traditional: A New Paradigm for Pakistani Schools By Mahjabeen Quadri B.S. Architecture Studies University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, 2001 Submitted to the Department of Architecture in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Architecture Studies at the MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY June 2003 JUL 0 2 2003 Copyright@ 2003 Mahjabeen Quadri. Al rights reserved LIBRARIES The author hereby grants to MIT permission to reproduce and to distribute publicly paper and electronic copies of this thesis document in whole or in part. Signature of Author: Mahjabeen Quadri Departm 4t of Architecture, May 19, 2003 Certified by:- Reinhard K. Goethert Principal Research Associate in Architecture Department of Architecture Thesis Supervisor Accepted by: Julian Beinart Departme of Architecture Chairman, Department Committee on Graduate Students ROTCH Thesis Committee Reinhard Goethert Principal Research Associate in Architecture Department of Architecture Massachusetts Institute of Technology Edith Ackermann Visiting Professor Department of Architecture Massachusetts Institute of Technology Anna Hardman Visiting Lecturer in International Development Planning Department of Urban Studies and Planning Massachusetts Institute of Technology Hashim Sarkis Professor of Architecture Aga Khan Professor of Landscape Architecture and Urbanism Harvard University Beyond the Traditional: A New Paradigm for Pakistani Schools Beyond the Traditional: A New Paradigm for Pakistani Schools By Mahjabeen Quadri Submitted to the Department of Architecture On May 23, 2003 in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Master of Science in Architecture Studies Abstract Pakistan's greatest resource is its children, but only a small percentage of them make it through primary school. -

Malala Yousafzai: Youngest Winner of the Nobel Peace Prize by Colette Weil Parrinello

Nobel laureate Malala Yousafzai meets with some of the students of Yerwa Girls School in Maiduguri, Nigeria in 2017. Malala Yousafzai: Youngest Winner of the Nobel Peace Prize by Colette Weil Parrinello Blogger at 11 A friend of his at the British Broadcasting Malala didn’t plan on being an anonymous Corporation (BBC) asked if there was a teacher blogger. But when the Taliban threatened her or older student who would write a diary about right to learn, the safety of her friends and life under the Taliban for its Urdu website. family, and her school, everything changed. Nobody would do it. Malala overheard her Her family encouraged her, a girl, to learn father and said, “Why not me?” and speak freely about the importance of Malala’s blog was born under the fake name education. When she was 10, the Pakistani “Gul Makai,” which is the name of a heroine Taliban took over the Swat Valley, and her city, in a Pashtun folk story. Her first entry was on Mingora, in northwest Pakistan. The Taliban January.3, 2009, and was titled “I am Afraid.” bombed girls’ schools, threatened people, Her blog became a success. She wrote forbad women from going outside, banned TV, about girls getting an education, her fear of the cinema, and DVDs, and murdered those who Taliban and the loss of her school, how much didn’t follow their edicts. In December 2008, the she loved learning, and her worry about her Taliban issued a demand—no girls shall go to family and friends. school. Many students and teachers in Malala’s school stayed home out of fear. -

DR. RAFAQAT ALI AKBAR Professor of Education Institute of Education and Research University of the Punjab, Lahore

CURRICULUM VITA DR. RAFAQAT ALI AKBAR Professor Of Education Institute of Education and Research University of the Punjab, Lahore Address : ER-1 Staff Colony University of the Punjab, Quaid–e-Azam Campus (New Campus) Lahore E-mail : [email protected] [email protected] Office No. : 092-42-99231592 Cell: : 092-333-4430282 Academic Examination Year Institution Post Doctoral 2007-08 School of Education University of Birmingham, UK Fellowship Ph.D (Edu) 2001 University of Arid Agriculture, Rawalpindi M.Ed. (Sc) 1988 University of the Punjab, Lahore M.A. (Isl.Std.) 1987 University of the Punjab, Lahore B.S.Ed 1986 Govt. College of Education for Science, Town Ship, Lahore) F.Sc. 1981 Govt. Degree College Pattoki (Kasure) S.S.C 1978 Govt. High School Pattoki (Kasure) Professional Experience Professor, Department of Elementary Education, Institute of Education and Research, University of the Punjab, Lahore since 04-06-2008 to date. Associate Professor, Department of Elementary Education, Institute of Education and Research, University of the Punjab, Lahore since 10-09-2003 to 03-06-2008. Lecturer, Department of Elementary Education, Institute of Education and Research, University of the Punjab, Lahore since 22-03-1992 to 09-09-2003. Secondary School Teacher (science) University Laboratory School, Institute of Education and Research, University of the Punjab, Lahore since18-10-1988 to 22-03- 1992 1 Research Work A study of Mentor’s Roles a Gap between Theory and Practice (Post Doc Research fellowship 2008). A study of practice Teaching of Prospective Secondary School Teachers and development of practice Teaching Model (Ph.D. -

Quality Indicators in Teacher Education Programmes

Pakistan Journal of Social Sciences (PJSS) Vol. 30, No. 2 (December 2010), pp. 401-411 Quality Indicators in Teacher Education Programmes Muhammad Dilshad Assistant Professor, Department of Education, The Islamia University of Bahawalpur, Pakistan. [email protected] Hafiz Muhammad Iqbal Dean, Faculty of Education, University of the Punjab, Lahore, Pakistan. [email protected] Abstract At present a number of initiatives are being taken from various bodies for bringing qualitative reform in teacher education in Pakistan. To make these measures more focused and cost effective, there is a dire need to identify the significant areas/aspects of quality improvement. This paper presents the findings of the study which was focused on identifying the quality indicators in teacher education programmes and ranking them in the light of perceptions of teacher educators working at public university of Pakistan. It was found that faculty of teacher education institutions (TEIs) considered 17 indicators most important, 12 indicators moderately important and one indicator little important. ‘Teachers’ professional development’ received top most rating whereas ‘publication of self assessment reports’ was the bottom ranked indicator. This study is significant in the sense that it generated primary data about quality assurance in teacher education in Pakistan. The findings of this study have implications for HEC, Accreditation Council for Teacher Education and TEIs’ management for highlighting the important aspects which may be focused for quality improvement in teacher education programmes. For assessing quality of academic programmes using the suggested quality indicators, it is recommended that standards in the form of statements may be formulated for each indicator. Keywords: Quality assurance; Quality indicators; Teacher education; Education quality; Quality control; Self assessment I. -

Curriculum Vitae

CURRICULUM VITAE NAME : PROF. DR. BASHIR AHMAD FATHER’S NAME : CHAUDHRY WALI MUHAMMAD DESIGNATION : PROFESSOR OF PHARMACOLOGY POSTAL ADDRESS (Off.) : UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF PHARMACY, UNIVERSITY OF THE PUNJAB, ALLAMA IQBAL CAMPUS, LAHORE, PAKISTAN. (Res.) : HOUSE NO. 507-A, STREET NO. 24 GULISTAN COLONY DHARAMPURA LAHORE –15, PAKISTAN. PHONE NOS. : 042-37356508 (Office) : 042-35912011 (Residence) MOBILE NO. : 0300-4250948 FAX NO. : 042-9211624 E-MAIL ADDRESS : [email protected] DATE OF BIRTH : 28.05.1952 RELIGION : ISLAM QUALIFICATIONS (ACADEMIC & PROFESSIONAL): Name of Subjects Year Name of Marks Division & Exam. Board/ University University Merit S.S.C. Exam. Urdu, Eng. Maths. Phys. 1967 B.I.S.E. Lahore 682/900 Ist Chem. Pers. Soc. Studies Intermediate Eng. Urdu. Phys. Chem. Biol. 1969 -do- 633/1000 Ist B. Pharm. Physiology, Pharm. Maths. 1970 Punjab 215/300 Ist Ist Prof. University, 4th in the Lahore order of merit B. Pharm. Pharmacology, 1971 -do- 342/500 Ist IInd prof. Pharmacognosy Ist in the Order of Merit B. Pharm. Pharmaceutics, Pharm-Chem. 1972 -do- 803/1500 IInd IIIrd prof. M. Pharm. Pharmaceutics Pharm-Chem. 1974 -do- 660/1000 Ist Biol. Sci. Thesis & Viva IInd in the Voce Order of Merit Ph.D. Pharmacology 1989 University of Wales, U.K. Post- Pharmacology 1995 KCOM* Doctoral - Missouri Fellowship 1996 U.S.A *Kirksville College Of Osteopathic Medicine Kirksville Missouri, U.S.A. 1 FIELD OF SPECIALIZATION PHARMACY (PHARMACOLOGY) 1) M. PHARMACY THESIS: Research work on the project entitled “Preparation and Assay of Pancreatin” was carried out under the supervision of Professor Dr. M. Ashraf and thesis was submitted to University of the Punjab Lahore – Pakistan for degree of M. -

Role of Universities in the Transformation of Students: a Study of University in Punjab Pakistan

International Journal of Academic Research in Business and Social Sciences Sep 2015, Vol. 5, No. 9 ISSN: 2222-6990 Role of Universities in the Transformation of Students: A Study of University in Punjab Pakistan Farah Naz Assistant Professor, School of Social Science and Humanities, University of Management & Technology, Lahore, Pakistan Email: [email protected] Dr. Hasan Sohaib Murad Professor, The Rector, University of Management and Technology, Lahore, Pakistan) DOI: 10.6007/IJARBSS/v5-i9/1813 URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.6007/IJARBSS/v5-i9/1813 Abstract The role of universities in directing, administrating and facilitating students to achieve their objectives and produce inner momentum to enable them to respond to challenges as professionals and learned beings, is of the utmost importance and a required ingredient to meet the cherished ends of an education system. The main objective of this study is to find out the role of universities in transforming the students as true professionals. The research is conducted on one university of Lahore, Pakistan. It includes the analysis of data of students collected at their entry and exit level. The gap analysis between the two clearly defines the role of university in transforming the students. Keywords: Universities, Transform, Students Introduction The typical role of education is to shift the knowledge of one generation, usually the formal, to the other, usually the next (A W Astin, 1977; Schultz, 1971). The educational institutes facilitate and formalize this role (Lambooy, 2004). The institutes of higher education have an additional role, as discussed by De Weert (1999), of equipping the students with knowledge of their being (Gibbons, 1998), of their self (Alexander W Astin, 1977), of their environment (Gumport, 2002), of the society they are living in (Jarvis, 2001), of the expectations of their parents (Weinstein & Weinstein, 2002), or in more comprehensive vocabulary, the meaning of life, in addition to the shifting of the knowledge of their yester generation. -

Department of Tourism & Northern Studies MAKING LAHORE A

Department of Tourism & Northern Studies MAKING LAHORE A BETTER HERITAGE TOURIST DESTINATION Muhammad Arshad Master thesis in Tourism- November 2015 Abstract In recent past, tourism has become one of the leading industries of the world. Whereas, heritage tourism is one of the fastest growing sectors in tourism industry. The tourist attractions especially heritage attractions play an important role in heritage destination development. Lahore is the cultural hub of Pakistan and home of great Mughal heritage. It is an important heritage tourist destination in Pakistan, because of the quantity and quality of heritage attractions. Despite having a great heritage tourism potential in Lahore the tourism industry has never flourished as it should be, because of various challenges. This Master thesis is aimed to identify the potential heritage attractions of Lahore for marketing of destination. Furthermore, the challenges being faced by heritage tourism in Lahore and on the basis of empirical data and theoretical discussion to suggest some measures to cope with these challenges to make Lahore a better heritage tourist destination. To accomplish the objectives of this thesis, various theoretical perspectives regarding tourist destination development are discussed in this thesis including, destination marketing and distribution, pricing of destination, terrorism effects on destination, image and authenticity of destination. The empirical data is collected and analyze on the basis of these theories. Finally the suggestions are made to make Lahore a better heritage tourist destination. Key words: Heritage tourism, tourist attractions, tourist destination, destination marketing, destination image, terrorism, authenticity, Lahore. 2 | Page Acknowledgement Working with this Master thesis has been very interesting and challenging at a time. -

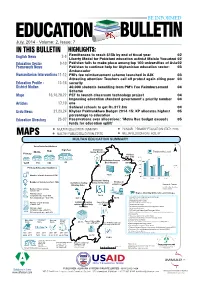

Education Bulletin 1 Updated

July, 2014 - Volume: 2, Issue: 7 IN THIS BULLETIN HIGHLIGHTS: English News 2-8 Remittances to reach $15b by end of fiscal year 02 Liberty Medal for Pakistani education activist Malala Yousafzai 02 Education Sector 9-10 Pakistan fails to make place among top 100 universities of Asia02 Framework News Pakistan to continue help for Afghanistan education sector: 03 Ambassador Humanitarian Interventions11-12 PM's fee reimbursement scheme launched in AJK 03 Attracting attention: Teachers call off protest again citing poor 03 Education Profile - 13-15 security District Multan 40,000 students benefiting from PM's Fee Reimbursement 04 Scheme Maps 16,18,20,22 PEF to launch classroom technology project 04 Improving education standard government’s priority number 04 Articles 17,19 one Sahiwal schools to get Rs.317.8m 04 Urdu News 21,23,24 Khyber Pakhtunkhwa Budget 2014-15: KP allocates highest 05 percentage to education Education Directory 25-37 Reservations over allocations: ‘Metro Bus budget exceeds 05 funds for education uplift’ MULTAN EDUCATION SUMMARY PUNJAB - PRIMARY EDUCATION STATS-2013 MAPS MULTAN PUBLIC EDUCATION STATS MULTAN EDUCATION FACILITY MULTAN EDUCATION SUMMARY Level wise Institutions High Sec Institutions ¯ Middle High having Electricity Teachers by Level Primary Children (Age 6-16) Institutions having Out-ofschool 1,285 199 140 20 Boundarywall (Girls) 65.6% Primary Education Statistics Number of male teachers 1936 76.5% 3.4% Institutions having Children in Number of female teachers 1896 Institutions having Toilets for Students private -

Identification of Problems Faced by Heads of Teacher Education Institutions in Achieving New Millennium Goals

International Journal of Social Sciences and Education ISSN: 2223-4934 Volume: 2 Issue: 1 January 2012 Identification of Problems Faced by Heads of Teacher Education Institutions in Achieving New Millennium Goals By M. Shoaib Anjum, M. Zafar Iqbal, Uzma Rao Ph.D. Scholars, University of Education Township, Lahore Abstract Teacher education institutions play an important role in the personal and professional development of teachers and in the improvement of institutions. The role of head is very important in teacher education institution. The purpose of this study was to identify the problems of heads of teacher education institutes to achieve the goals of new millennium. The study was qualitative in nature. Semi- structured interviews were conducted in order to identify the problems of heads of teacher education institutions. All the heads of teachers’ education institutes of Punjab was targeted population of the study. A sample of twenty (20) heads of teacher education institutes was selected trough convenient sampling technique. The questions of interview were validated through five experienced professors of the corresponding field. The collected data was analyzed by descriptive coding technique. The results of the study revealed that, in ordered to achieve the goals of new millennium, heads of teacher education institutes were facing problems like shortage of funds, political pressure, teaching aid material and parents’ attitude. Keywords: Teacher Education Institutes, Goals, New Millennium Introduction Education is essential for the overall personality developments of human beings. It plays an important role to change the attitude and behavior of the individual. In the process of education, people learn how they can better survive in the fast progressing world. -

Fall 2016 Newsletter Varuni Bhatia

CE N T E R F O R S O U T H A S I A N S T U D I E S Michigan Newsletter Fall 2016 University of Varuni Bhatia Letter from the Director A Conversation with out brilliantly in the two films) are the changes within the Jat agrarian economy. Your films Nakul Sawhney tease this aspect out, such that gender and reli- gion do not become simply cultural components I’d like to welcome students, religious polemic, contemporary mothers, river port bureaucrats, rural but are also very strongly linked to the political community members, staff, and governance, and two film screenings development, justice and tolerance in economy of the region. I am curious to have you faculty to the 2016-17 academic year about Indian elections and anti- Islamist thought, Buddhist concepts of talk a bit more about this. and invite you to be a part of an excit- Muslim violence (see p. 3). The CSAS mind, colonial medical jurisprudence, When I was working on Izzatnagari, in December ing year at the Center for South Asian also co-sponsored lectures organized medieval Indian public sphere, Bolly- 2010, I had also traveled to Muzaffarnagar then. Studies (CSAS). by undergraduate students including wood and Hollywood, and caste in elite On April 1, 2016 the CSAS welcomed Nakul Can you tell us a little bit about your Film and My aim was to understand what was happening in the Sikh Students Association and contemporary institutions (see p. 16). Sawhney to U-M for the screening of his latest Television Institute of India (FTII) days and your Last year the Center hosted several the Jat belt outside of Haryana. -

Issues of Gender in Education in Pakistan

Issues of gender in education in Pakistan Fareeha Zafar Pakistan, with an area of 803,940 square kilometres, borders India qualified and trained teachers. Other issues recognised in the in the east and southeast, Iran in the southwest, Afghanistan in PRSP include teacher absenteeism, high dropout rates and gender the north and northwest, and the Arabian Sea in the south. The inequalities. The MDGs provide a common vision of a much better country is made up of three territories (Islamabad Capital Territory, world by 2015: where severe poverty is cut in half; child mortality the Federally Administered Tribal Areas, and the Federally is greatly decreased; gender differences in primary and secondary Administered Northern Areas) and four provinces (Balochistan, education are removed; and women are greatly empowered. North-West Frontier Province, Punjab, and Sindh). The most Gender issues are seen as being highly relevant to achieving all populous of these provinces is Punjab, which is home to roughly the MDGs, however in the case of Pakistan, at the present rate of half the country’s total population of 148.4 million (2003).i progress none of the goals are likely to be achieved. Women constitute a little under half the population. The issue of gender has also been addressed in the National Policy According to the Constitution of Pakistan, the state shall: ‘remove and Action Plan 2001 to combat child labour. The officially illiteracy and provide free and compulsory secondary education acknowledged number of child labourers in the country is 3.3 within minimum possible period’ (Article 37-B, Constitution of millioniii of which 0.9 million are girls.