Consultation on Ministry to and with Youth

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Unitarian Universalist Association Annual Report June 2008

Unitarian Universalist Association Annual Report June 2008 William G. Sinkford-President Kathleen Montgomery-Executive Vice President 1 INTRODUCTION The Association’s mission for the staff is to: 1. Support the health and vitality of Unitarian Universalist congregations as they minister in their communities. 2. Open the doors of Unitarian Universalism to people who yearn for liberal religious community. 3. Be a respected voice for liberal religious values. This report outlines for you, by staff group, the work that has been done on your behalf this year by the staff of the Unitarian Universalist Association. It comes with great appreciation for their extraordinary work in a time of many new initiatives in response to the needs of our faith and our congregations. If you have questions in response to the information contained here, please feel free to contact Kay Montgomery ([email protected]). William G. Sinkford, President Kathleen Montgomery, Executive Vice President 2 CONTENTS STAFF GROUPS: Advocacy and Witness Page 4 Congregational Services Page 6 District Services Page 13 Identity Based Ministries Page 15 Lifespan Faith Development Page 16 Ministry and Professional Leadership Page 24 Communications Page 27 Beacon Press Page 31 Stewardship and Development Page 33 Financial Services Page 36 Operations / Facilities Equal Employment Opportunity Report Page 37 3 ADVOCACY AND WITNESS STAFF GROUP The mission of the Advocacy and Witness staff group is to carry Unitarian Universalist values into the wider world by inserting UU perspectives into public debates of the day. Advocacy and Witness staff members work closely in coalitions with other organizations which share our values, as well as local UU congregations, to be effective in this ministry internationally, nationally, and in state and local efforts. -

59Th Annual General Asseembly

59TH ANNUAL GENERAL ASSEMBLY VIRTUAL GENERAL ASSEMBLY|JUNE 24–28, 2020 SUMMARY SCHEDULE ET/CT EDT CDT Wednesday 6/24 Thursday 6/25 Friday 6/26 Saturday 6/27 Sunday 6/28 9:00 AM 8:00 AM Morning Worship Morning Worship Morning Worship (Available On-Demand) (Available On-Demand) (Available On-Demand) 9:30 AM 8:30 AM 10:00 AM 9:00 AM Sunday Morning Worship East 10:30 AM 9:30 AM Workshops Workshops Workshops 11:00 AM 10:00 AM Cofee Hour 11:30 AM 10:30 AM 12:00 PM 11:00 AM Featured Speaker Featured Speaker Featured Speaker Featured Speaker 12:30 PM 11:30 AM 1:00 PM 12:00 PM Sunday Morning Worship West 1:30 PM 12:30 PM 2:00 PM 1:00 PM General Session 2 General Session 4 General Session 5 Cofee Hour 2:30 PM 1:30 PM 3:00 PM 2:00 PM 3:30 PM 2:30 PM Organizing Your Congregation to 4:00 PM 3:00 PM #UUTheVote Workshops General Session 3 COIC Workshops General Session 6 (COIC Report) 4:30 PM 3:30 PM 5:00 PM 4:00 PM Report Report 5:30 PM 4:30 PM Orientation 6:00 PM 5:00 PM Service of the Synergy Bridging Ware Lecture Living Tradition Worship 6:30 PM 5:30 PM 7:00 PM 6:00 PM 7:30 PM 6:30 PM Welcoming Refections Refections Refections Celebration 8:00 PM 7:00 PM 8:30 PM 7:30 PM General Session 1 9:00 PM 8:00 PM Featured Speaker Featured Speaker Featured Speaker 9:30 PM 8:30 PM 10:00 PM 9:00 PM UU Fun Night CONTENTS Welcome to Virtual GA.............................................................. -

Summit on Youth Ministry Report

Summit on Youth Ministry Report July 16–20, 2007 Simmons College Boston, Massachusetts Greetings! We are delighted to share with you a new imagination of Unitarian Universalist youth ministry and multigenerational faith community. This vision comes from a diverse group of youth and adult stakeholders who gathered at Simmons College in Boston, Massachusetts, for the Summit on Youth Ministry. Our task was to imagine and shape a youth ministry that serves all Unitarian Universalist youth. Our work was grounded in the two-year Consultation on Ministry To and With Youth, a process that engaged more than five thousand Unitarian Universalists in conversations about the role and direction of youth ministry in our Association. Thousands of Unitarian Universalists have contributed to this new vision. We envision a youth ministry that is central to the articulated mission of Unitarian Universalism, offers multiple pathways for involvement in our faith communities, and is congregationally based; multigenerational; spirit-centered; counter-oppressive, multicultural, and radically inclusive. Numerous factors impact our ability to serve the members of our congregations. Our programming, worship, social justice work, and resources work for some, but do not effectively minister to and with all Unitarian Universalists. The issues facing youth ministry reflect the forces and trends affecting our movement as a whole. This report offers recommendations for strengthening and broadening our ministry throughout our faith communities. The publication of this report does not mark the end of a process. It marks a beginning. Now is the time to create the ministry our youth deserve. Take this report home to your congregations and look for more updates and resources for sharing it at www.uua.org/aboutus/governance/ boardtrustees/youthministry. -

Obituaries Professional Religious Leaders 2019–2020

OBITUARIES Professional Religious Leaders 2019–2020 VIRTUAL GENERAL ASSEMBLY JUNE 2020 © Unitarian Universalist Association 2020 Contents ANDREW C. BACKUS ...........................................................................................................................................................................1 GEORGE BRIGGS ...................................................................................................................................................................................2 BARBARA D. BURKE .............................................................................................................................................................................3 CAROLYN W. COLBERT .......................................................................................................................................................................4 DOROTHY M. EMERSON ....................................................................................................................................................................5 HEATHER LYNN HANSON .................................................................................................................................................................6 HUGO J. HOLLERORTH .......................................................................................................................................................................7 DAVID A. JOHNSON .............................................................................................................................................................................9 -

SEXUALITY EDUCATION Eva S. Goldfarb Department of Health And

SEXUALITY EDUCATION Eva S. Goldfarb Department of Health and Nutrition Sciences College of Education and Human Services Montclair State University, Montclair, NJ [email protected] Norman A. Constantine Center for Research on Adolescent Health and Development, Public Health Institute, Oakland, CA, and School of Public Health, University of California, Berkeley, CA [email protected] To appear in: B.B. Brown & M. Prinstein (Eds.). (2011). Encyclopedia of adolescence. NY: Academic Press. REVISED: January 9, 2011 1 Synopsis Sexuality education comprises the lifelong intentional processes by which people learn about themselves and others as sexual, gendered beings from biological, psychological and socio-cultural perspectives. It takes place through a potentially wide range of programs and activities in schools, community settings, religious centers, as well as informally within families, among peers, and through electronic and other media. Sexuality education for adolescents occurs in the context of the biological, cognitive, and social-emotional developmental progressions and issues of adolescence. Formal sexuality education falls into two main categories: behavior change approaches, which are represented by abstinence-only and abstinence-plus models, and healthy sexual development approaches, represented by comprehensive sexuality education models. Evaluations of program effectiveness, largely based on the outcomes of behavior change models, provide strong evidence that abstinence-only programs are ineffective, and mixed -

A Brief History of UUCLR

The Unitarian Universalist Church of Little Rock A Brief History The seeds of liberal religion that ultimately grew into the Unitarian Universalist Church of Little Rock were sown by Universalists around 1900 when a Universalist congregation was active in Little Rock for almost twenty years. In the 1930s, the Unitarians looked into forming a Unitarian church but did not find sufficient interest at that time. However, after WWII the climate was more favorable, and this time the Unitarians were successful in establishing a foothold in Little Rock in the form of a Unitarian Fellowship. (For more information on the earlier roots of Universalism see the Appendix at the end of this document.) UUCLR’s Beginnings – The Fellowship Years 1950 – 1959 In response to ads soliciting interest in Unitarianism placed in the Little Rock newspapers in the late summer and fall of 1950, several latent Arkansas Unitarians, including Dr. E. E. Cordrey and Felix Arnold, organized a meeting on Sunday, October 15, 1950, at Temple B’Nai Israel in Little Rock. Dr. Cordrey spoke on “Why I Am a Unitarian.” Two weeks later, when the Reverend R. B. Gibbs, Regional Director of the Southwestern Unitarian Conference, spoke to the group on “Faith Without Fear,” around sixteen persons had signed the membership book. This number was sufficient for the group to apply for affiliation with the American Unitarian Association (AUA), and on October 30, 1950, the Little Rock Unitarian Fellowship formally came into being. With its small group of charter members, the Little Rock Fellowship held together and slowly grew, passing around the leadership responsibilities, arranging weekly services at the Sam Peck Hotel, and setting up a Sunday school. -

Parish Messenger Accompanist Needed

October 2012 Parish Messenger Accompanist Needed .........................7 Auctions................................... 3, 10, 12 Unitarian Universalist Church Board Chair Report ...........................12 Book Recommendation ...................... 8 of Brunswick CALENDAR ........................................ 13 Camden International Film Festival... 5 Carter Ruff ......................................... 12 Charity with Soul................................. 8 Congregational Meeting ..................... 2 Council Meeting................................... 9 Death Remains Discussion ................ 8 Doll House Raffle................................. 9 Flowers and Focal Points................. 10 Joys and Sorrows ...............................5 jUUst Desserts..................................... 6 How to Reach Us................................. 2 Larry Lemmel Piano Concert.............. 4 Minister’s Musings..............................3 New Member: Penny Elwell................ 4 New UU Class ...................................... 6 Religious Education............................2 Side Door Coffee House ................... 11 Sunday Services.................................. 1 Women’s Alliance................................9 Working for Justice...........................11 ALL SERVICES AT 10:00 AT THE MINNIE BROWN CENTER October 7 - “Standing on the Side of Love” What makes a family? Love. Service led by the Worship Committee with participation from others, including special guest speaker Phil Richardson. Music provided by Peter -

Resistance and Transformation: Unitarian Universalist Social Justice History

RESISTANCE AND TRANSFORMATION: UNITARIAN UNIVERSALIST SOCIAL JUSTICE HISTORY A Tapestry of Faith Program for Adults BY REV. COLIN BOSSEN AND REV. JULIA HAMILTON © Copyright 2011 Unitarian Universalist Association. This program and additional resources are available on the UUA.org web site at www.uua.org/re/tapestry 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS WORKSHOP 1: INTRODUCTIONS................................................................................................................... 16 WORKSHOP 2: PROPHETIC, PARALLEL, AND INSTITUTIONAL ............................................................. 27 WORKSHOP 3: THE RESPONSE TO SLAVERY ............................................................................................ 42 WORKSHOP 4: THE NINETEENTH CENTURY WOMEN'S PEACE MOVEMENT .................................... 58 WORKSHOP 5: JUST WAR, PACIFISM, AND PEACEMAKING .................................................................. 77 WORKSHOP 6: RELIGIOUS FREEDOM ON THE MARGINS OF EMPIRE ................................................. 96 WORKSHOP 7: UTOPIANISM ........................................................................................................................ 106 WORKSHOP 8: COUNTER-CULTURE .......................................................................................................... 117 WORKSHOP 9: FREE SPEECH ....................................................................................................................... 128 WORKSHOP 10: TAKING POLITICS PUBLIC ............................................................................................. -

2021.05.09 When Unitarian Meets Universalist

“When Unitarian Meets Universalist: An Origin Story” Sermon by Rev. Joan Javier-Duval Unitarian Church of Montpelier May 9, 2021 Reading “Ours is a story of faith,” Elizabeth Tarbox from Evening Tide: Meditations Sermon As human beings, we are drawn to stories of our origins. We wonder, as Paul Gaugin expresses in his painting of the same title, “Where Do We Come From? What Are We? Where Are We Going?” Unitarian Universalism also has an origin story. In reality, it has multiple origin stories as no single story really ever tells the whole tale. And so it goes with the story of how the faith movement that this congregation is a part of came into being. It is a story of working through differences, finding common ground, and seeking union in order to build power for the common good. Some of those who were key characters are still alive today and many more have joined the ancestors. As we mark the 60th anniversary of the formation of the Unitarian Universalist Association, I want to share with you this morning some nuggets from the story of how the Unitarian and Universalist denominations came together. First, let me place this congregation, the Unitarian Church of Montpelier, into context. This church’s origin story begins in the 1860s when talk began of starting a “liberal church” in Montpelier, meaning a Christian church of “liberal” rather than “orthodox” Christian theology. The Rev. Charles Allen, with his evangelistic zeal, was key in drawing together the group of Universalists, spiritualists, and other liberals into a formalized fellowship, called the Church of the Messiah. -

In Their Own Words

In Their Own Words ADIRE CLOTH. All rights reserved, University of Denver Museum of Anthropology. A Conversation With Participants in the Black Empowerment Movement Within the Unitarian Universalist Association January 20, 2001 _______ EDITED BY ALICIA MCNARY FORSEY In Their Own Words Published by Starr King School for the Ministry 2441 Le Conte Avenue Berkeley, California 94709 tel. 510 845 6232 fax 510 845 6273 http://www.sksm.edu http://online.sksm.edu The Starr King School for the Ministry educates women and men for religious leadership, especially Unitarian Universalist ministry. We focus our concerns on congregational life and public service in the wider community. Rooted in the liberal and liberating values of Unitarian Universalism, we approach education as an engaged, relational practice through which human beings develop their gifts and deepen their calling to be of service to the world. Front cover: Yoruba women in Nigeria make a type of resist-dyed cloth that they call adire. They make some adire by folding, tying, and/or stitching cloth with raffia before dyeing. This is called adire oniko, after the word for raffia, iko. They also make another type, adire eleko, by painting or stenciling designs on the cloth with starch. Both types are dyed in indigo, a natural blue dye. For more information on West African textiles, visit http://www.du.edu/duma/africloth. Editor: Rev. Dr. Alicia McNary Forsey Transcription and layout: Cathleen Young Proofreader: Helene Knox Timeline: Julie Kain Photography: Becky Leyser, Alicia McNary Forsey Publication funded by the Fund for Unitarian Universalism No portion of this publication may be reproduced without the written permission of the publisher. -

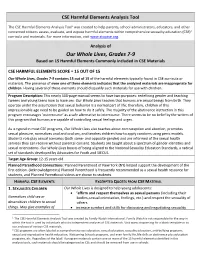

Our Whole Lives, Grades 7-9 Based on 15 Harmful Elements Commonly Included in CSE Materials

CSE Harmful Elements Analysis Tool The CSE Harmful Elements Analysis Tool1 was created to help parents, school administrators, educators, and other concerned citizens assess, evaluate, and expose harmful elements within comprehensive sexuality education (CSE)2 curricula and materials. For more information, visit www.stopcse.org. Analysis of Our Whole Lives, Grades 7-9 Based on 15 Harmful Elements Commonly Included in CSE Materials CSE HARMFUL ELEMENTS SCORE = 15 OUT OF 15 Our Whole Lives, Grades 7-9 contains 15 out of 15 of the harmful elements typically found in CSE curricula or materials. The presence of even one of these elements indicates that the analyzed materials are inappropriate for children. Having several of these elements should disqualify such materials for use with children. Program Description: This nearly 500-page manual seems to have two purposes: redefining gender and teaching tweens and young teens how to have sex. Our Whole Lives teaches that humans are sexual beings from birth. They operate under the assumption that sexual behavior is a normal part of life; therefore, children of this impressionable age need to be guided on how to do it safely. The majority of the abstinence instruction in this program encourages ‘outercourse’ as a safe alternative to intercourse. There seems to be no belief by the writers of this program that humans are capable of controlling sexual feelings and urges. As is typical in most CSE programs, Our Whole Lives also teaches about contraception and abortion, promotes sexual pleasure, normalizes anal and oral sex, and teaches children how to apply condoms using penis models. -

Assessing Sexual Health: an Online Guide for UUA Congregations

Assessing Sexual Health: An Online Guide For UUA Congregations By Rev. Debra W. Haffner Religious Institute January 2012 ©Reli[Type text] Page 1 Contents INTRODUCTION ..................................................................................................... 3 Building Block #1 CONGREGATION POLICIES AND ENVIRONMENT ............................. 5 Building Block #2 SEXUALLY HEALTHY RELIGIOUS PROFESSIONALS ........................ 11 Building Block #3 WORSHIP AND PREACHING ........................................................ 13 Building Block #4 PASTORAL CARE ........................................................................ 18 HOTLINES FOR REFERRALS ................................................................................... 24 Building Block #5 SEXUALITY EDUCATION FOR CHILDREN AND YOUTH ................... 25 Building Block #6 SEXUALITY EDUCATION FOR ADULTS .......................................... 29 Building Block #7 WELCOME AND FULL INCLUSION ................................................ 31 Building Block #8 SAFE CONGREGATIONS .............................................................. 38 Building Block #9 SOCIAL JUSTICE/SOCIAL ACTION ............................................... 42 CLOSING WORDS ................................................................................................. 46 2 | P a g e © Religious Institute ASSESSING SEXUAL HEALTH: AN ONLINE GUIDE FOR UUA CONGREGATIONS By Rev. Debra W. Haffner INTRODUCTION The Unitarian Universalist Association has a long standing commitment