Can Rights Undermine Trust? How Institutions Work and Why They Fail *

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Saga of Indian Scientists

BOOK Review scientists, all of them were born before Independence, 25 of them in the 19th century. Hoariest among them is our spirited THE SAGA OF nationalist mathematician, Radhanath Sikdar, famous for measuring the height of Mt. Everest. He is also ‘one of the earliest pioneers of popular science writing in the country’. INDIAN SCIENTISTS He was born in 1813. By Vinod Varshney Most of these scientists were exposed to western scientific culture and conducted some of their important research, if not all, in the well-equipped labs abroad, but their mission had always been to develop science and technology in India. Treading in the footsteps of their seniors, the younger lot too resolutely took upon themselves to grapple with post- independence challenges to promote scientific and technological capabilities constrained with meagre infrastructural resources. They indeed laid a credible foundation of the much-needed science and technology base in the country which has today mushroomed into over 5,000 labs where approximately 5 lakh scientists work. The bio-sketches have been written by seasoned science writers and journalists who have deployed their ingenuity in presenting multiple facets of their scientific work, thinking and personality and also events that helped mould their outlook. But this has been done in a tiny space – only three pages per scientist. In such a niggardly space they could not have satiated readers’ hunger to know the complete complex scenario which existed in their time and blow by blow account of their vision Title: INDIAN SCIENTISTS and spirit. THE SAGA OF INSPIRED MINDS Most bio-piece scribblers have attempted to explore the Author: Biman Basu, Sukanya Datta, heart, soul and time of the scientists, making them pleasurable T.V. -

A Journey to the Scientific World

A Journey to the Scientific World Ramesh C. Samanta JSPS post doctoral Fellow Chubu University, Japan June 15, 2016 India: Geographical Location and Description Total Area: 32,87,364 km2 (No. 7 in the world) Population: 1,251,695,584 (2015, No. 2 in the world) Capital: New Delhi Time Zone (IST): GMT + 5.30 hrs Number of States and Union Territories: 29 States and 7 Union Territories India: Languages and Religions In the history India has experienced several great civilizations in different part of it and they had different languages. This resulted several different languages: Majority from Indo Aryan civilization, Dravid civilization. Major Languages: Hindi and English Official Languages: Total 23 languages with countless dialect India is well known for its diversity of religious beliefs and practices. All the major religions of the world like Hinduism, Sikhism, Buddhism, Jainism, Islam and Christianity are found and practiced in India with complete freedom Weather in India Extreme climate of being tropical country !!! Hot summer (Temperature goes up to 50 oC) Windy monsoon (average rainfall 1000 mm per year) Pleasant Autumn Snowy winter in Northan part of India Indian Food Indian Spices Indian Curry North Indian Food South Indian Food Tourist Attractions in India Taj Mahal, Agra The Ganges, Varanasi Victoria memorial Hall , Kolkata Sea Beach, Goa India’s Great Personalities Netaji Subhas Jawaaharlal Rabindranath Mahatma Gandhi Chandra Bose Nehru Tagore Swami Sarojini Naidu Vivekananda B. R. Ambedkar Sri Aurobindo Indian Nobel Laureates Rabindranath Tagore C. V. Raman Har Gobind Khorana Nobel Prize in Nobel Prize in Physics, 1930 Nobel Prize in Medicine, Literature, 1913 1968 Mother Teresa Venkatraman Ramakrishnan Kailash Satyarthi Nobel Peace Prize 1979 Nobel Prize in chemistry 2009 Nobel Peace Prize 2014 Indian Scientists Sir Jagadish Chandra Bose (1858-1937): Known for pioneering investigation of radio and microwave optics and plant biology. -

31 Indian Mathematicians

Indian Mathematician 1. Baudhayana (800BC) Baudhayana was the first great geometrician of the Vedic altars. The science of geometry originated in India in connection with the construction of the altars of the Vedic sacrifices. These sacrifices were performed at certain precalculated time, and were of particular sizes and shapes. The expert of sacrifices needed knowledge of astronomy to calculate the time, and the knowledge of geometry to measure distance, area and volume to make altars. Strict texts and scriptures in the form of manuals known as Sulba Sutras were followed for performing such sacrifices. Bandhayana's Sulba Sutra was the biggest and oldest among many Sulbas followed during olden times. Which gave proof of many geometrical formulae including Pythagorean theorem 2. Āryabhaṭa(476CE-550 CE) Aryabhata mentions in the Aryabhatiya that it was composed 3,600 years into the Kali Yuga, when he was 23 years old. This corresponds to 499 CE, and implies that he was born in 476. Aryabhata called himself a native of Kusumapura or Pataliputra (present day Patna, Bihar). Notabl e Āryabhaṭīya, Arya-siddhanta works Explanation of lunar eclipse and solar eclipse, rotation of Earth on its axis, Notabl reflection of light by moon, sinusoidal functions, solution of single e variable quadratic equation, value of π correct to 4 decimal places, ideas circumference of Earth to 99.8% accuracy, calculation of the length of sidereal year 3. Varahamihira (505-587AD) Varaha or Mihir, was an Indian astronomer, mathematician, and astrologer who lived in Ujjain. He was born in Avanti (India) region, roughly corresponding to modern-day Malwa, to Adityadasa, who was himself an astronomer. -

Stamps of India - Commemorative by Prem Pues Kumar [email protected] 9029057890

E-Book - 26. Checklist - Stamps of India - Commemorative By Prem Pues Kumar [email protected] 9029057890 For HOBBY PROMOTION E-BOOKS SERIES - 26. FREE DISTRIBUTION ONLY DO NOT ALTER ANY DATA ISBN - 1st Edition Year - 1st May 2020 [email protected] Prem Pues Kumar 9029057890 Page 1 of 76 Nos. YEAR PRICE NAME Mint FDC B. 1 2 3 1947 1 21-Nov-47 31/2a National Flag 2 15-Dec-47 11/2a Ashoka Lion Capital 3 15-Dec-47 12a Aircraft 1948 4 29-May-48 12a Air India International 5 15-Aug-48 11/2a Mahatma Gandhi 6 15-Aug-48 31/2a Mahatma Gandhi 7 15-Aug-48 12a Mahatma Gandhi 8 15-Aug-48 10r Mahatma Gandhi 1949 9 10-Oct-49 9 Pies 75th Anni. of Universal Postal Union 10 10-Oct-49 2a -do- 11 10-Oct-49 31/2a -do- 12 10-Oct-49 12a -do- 1950 13 26-Jan-50 2a Inauguration of Republic of India- Rejoicing crowds 14 26-Jan-50 31/2a Quill, Ink-well & Verse 15 26-Jan-50 4a Corn and plough 16 26-Jan-50 12a Charkha and cloth 1951 17 13-Jan-51 2a Geological Survey of India 18 04-Mar-51 2a First Asian Games 19 04-Mar-51 12a -do- 1952 20 01-Oct-52 9 Pies Saints and poets - Kabir 21 01-Oct-52 1a Saints and poets - Tulsidas 22 01-Oct-52 2a Saints and poets - MiraBai 23 01-Oct-52 4a Saints and poets - Surdas 24 01-Oct-52 41/2a Saints and poets - Mirza Galib 25 01-Oct-52 12a Saints and poets - Rabindranath Tagore 1953 26 16-Apr-53 2a Railway Centenary 27 02-Oct-53 2a Conquest of Everest 28 02-Oct-53 14a -do- 29 01-Nov-53 2a Telegraph Centenary 30 01-Nov-53 12a -do- 1954 31 01-Oct-54 1a Stamp Centenary - Runner, Camel and Bullock Cart 32 01-Oct-54 2a Stamp Centenary -

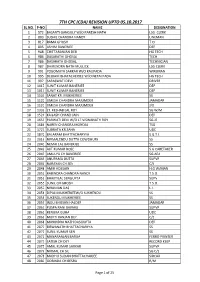

CDA WEB UPDATE.Xlsx

7TH CPC (CDA) REVISION UPTO 05.10.2017 SL.NO.P-NO NAME DESIGNATION 1 572 BASANTI GANGULY W/O PARESH NATH LSG CLERK 2 803 SUSHIL CHANDRA NANDY LINEMAN 3 817 RAMA GHOSH T.O. 4 895 ASHIM BANERJEE DEP 5 948 CHITTARANJAN DEB HG TECH 6 986 DASARATHI GHOSAL TECH 7 986 DASARATH GHOSAL TECHNICIAN 8 987 DHIRENDRA NATH MULLICK LSG CLERK 9 991 YOGOMAYA SARKAR W/O KALIPADA WIREMAN 10 995 DEBJANI BHATACHERJEE W/O NETAI PADA HG TECH 11 997 SARASWATI DEVI DRIVER 12 1017 SUNIT KUMAR BANERJEE DEP 13 1017 SUNIT KUMAR BANERJEE DEP 14 1107 SANAT KR. MUKHERJEE SS 15 1120 UMESH CHANDRA MAJUMDER JAMADAR 16 1120 UMESH CHANDRA MAJUMDER J/D 17 1332 LT. KESHAB LAL ROY SG W/M 18 1524 KAILASH CHAND JAIN DEP 19 1655 PARWATI DEVI W/O LT.VISWANATH ROY SG.JE 20 1686 NAREN CHANDRA MONDAL TSO 21 1727 SUBRATA KR.SAHA UDC 22 1870 BALARAM BHATTACHARYYA S.G.T.I. 23 2016 NIRMALENDU DUTTA COWDHURY SS 24 2040 NEMAI LAL BANERJEE SS 25 2042 AJIT KUMAR BOSE S.G CARETAKER 26 2043 AMULYA CH BANERJEE SG.AEA 27 2045 ANUPAMA DUTTA SUPVR 28 2046 NARAYAN CH SEN C/J 29 2048 AMIR HOSSAIN H.G W/MAN 30 2052 RABINDRA CHANDRA NANDY T.S.O. 31 2053 BHAKTILAL SENGUPTA SUPV 32 2055 SUNIL CH GHOSH T.S.O. 33 2057 NIRANJAN DAS L.I. 34 2058 DIPALI MUKHERJEEW/O SUKHENDU SS 35 2058 SUKENDU MUKHERJEE SS 36 2059 INDU BHUSAN HALDER JAMADAR 37 2063 PUSPA RANI BAIRAGI SUPVR 38 2065 RENUKA GUHA UDC 39 2066 MUKTI RANJAN DEY C/S 40 2068 MANINDRA NATH DASGUPTA DEP 41 2070 BISWANATH BHATTACHARYYA SS 42 2071 SUNIL KUMAR SEN SS 43 2072 MANARANJAN BARUA FERRO PRINTER 44 2073 SATISH CH DEY RECORD KEEP 45 2075 AMAL KUMAR SARKAR SUPVR 46 2076 NIRMAL CH SIL SG C/S 47 2078 MADHU SUDAN BHATTACHARJEE SIRCAR 48 2080 GOBINDA CH BESRA R/M Page 1 of 25 SL.NO.P-NO NAME DESIGNATION 49 2083 SUSHIL KR GHOSH C.O. -

Purnangshu Kumar Roy and the S.N. Bose Tradition in Theoretical Physics by Charles Wesley Ervin Email: Wes [email protected] August, 2016

Purnangshu Kumar Roy and the S.N. Bose Tradition in Theoretical Physics By Charles Wesley Ervin Email: [email protected] August, 2016 INTRODUCTION This year Calcutta University marks a historic mile- stone. One hundred years ago the university started teaching physics courses at the newly created College of Science and Technology. Three of the most brilliant Indian physicists of the twentieth century began their careers there. C.V. Raman, the first Palit Professor of Physics, was awarded the Nobel Prize in 1930 for his work on light scattering. The two young lecturers, Meghnad Saha and Satyendra Nath Bose, made major breakthroughs even sooner – Saha in 1920 for deriving the equation that accounts for the spectral classifica- tion of stars and Bose in 1924 for inventing the statisti- cal model that validated Einstein’s hypothesis of light quanta (the Bose Statistics). But this “golden age” of Calcutta physics was P. K. Roy (right) with Satyendra Nath Bose in London, short-lived. Saha went to Allahabad University in March, 1958. Roy studied theoretical physics with Bose for 1923, Bose decamped to Dacca University in 1924, ten years at Calcutta University and then earned his PhD at and Raman left in 1932 to become the first Indian di- Imperial College under Abdus Salam. This photo was taken when Bose came to London to be inducted Fellow of the rector of the Indian Institute of Science in Bangalore. Royal Society. Courtesy of Anjana Srivastava. After the war, however, there was something of a re- naissance. Bose returned in 1945 and gathered a team of talented research workers in the Physics Depart- ment and the Khaira Lab. -

IB ACIO 2014-15 Solved Question Paper

IB ACIO 2014-15 Solved Question Paper 1. Curcuma longa is the scientific name of which spice? A. Cumin B. Cloves C. Turmeric D. Coriander Answer: C 2. Bones found in the hands and feet as the percentage of total number of bones in the body of an adult human being is nearly equal to A. 20% B. 30% C. 40% D. 50% Answer: D 3. Europeans are believed to have brought potatoes to India in the 18th century. Which region of the world is believed to be the origin of potato cultivation? A. Eastern Ghana B. Southern Peru C. Portugal SPLessons D. West Indies Answer: A 4. Oymyakon is generally considered the coldest inhabited area on Earth. Which country Oymyakon is located . A. Mongolia B. Russia C. Greenland D. Iceland Answer: B 5. Which gland in the human body is also known as the third eye A. Pineal B. Pituitary C. Mammary D. Tear gland Answer: A 6. Leukaemia is a group of cancers that usually begins it the bone marrow and results in high numbers of which abnormal cells A. White blood cells B. Red blood cells C. Platelets D. All of these Answer: A SPLessons 7. During an earthquake, two places ‘A’ and ‘B’ record its intensity in Richter scale as 4.0 and 6.0 respectively. IN absolute terms, the ratio of intensity of the earthquake at ‘A’ to that of ‘B’ is: A. 2:3 B. 7:8 C. 141:173 D. 1:100 Answer: D 8. On a cool day in January, the temperature at a place fell below the freezing point and was recorded as -40° Centigrade. -

Journal of 200Th Session

FRIDAY, THE 12TH DECEMBER, 2003 (The Rajya Sabha met in the Parliament House at 11-00 a.m.) 11-00 a.m. 1. Reference by Chair The Chairman made a reference regarding the Second Anniversary of terrorist attack on the Parliament Building on the 13th December, 2001. The House observed silence, all Members standing, as a mark of respect to the memory of those who lost their lives in the tragedy. 11-03 a.m. 2. Starred Questions The following Starred Questions were orally answered:- Starred Question No.163 regarding Animal welfare schemes. Starred Question No.164 regarding History textbooks for class XII. Starred Question No.165 regarding Food for work programme in drought affected areas. Answers to remaining Starred Question Nos. 161, 162 and 166 to 180 were laid on the Table. 3. Unstarred Questions Answers to Unstarred Question Nos. 1092 to 1232 were laid on the Table. 12 Noon 4. Papers Laid on the Table Dr. Murli Manohar Joshi (Minister of Human Resource Development, Minister of Science & Technology and Minister of Ocean Development) laid on the Table a copy each (in English and Hindi) of the following papers:— (a) Fifth Annual Report and Accounts of the Indian National Centre for Ocean Information Services, Hyderabad, for the year 2002-2003, together with the Auditor's Report on the Accounts. (b) Review by Government on the working of the above Centre. RAJYA SABHA Shri Nitish Kumar (Minister of Railways) laid on the Table a copy each (in English and Hindi) of the following papers, under sub-section (1) of section 619A of the Companies Act, 1956:— (a) Annual Report and Accounts of the Mumbai Railway Vikas Corporation Limited, Mumbai, for the year 2002-2003, together with the Auditor's Report on the Accounts and the comments of the Comptroller and Auditor General of India thereon. -

In the High Court at Calcutta

IN THE HIGH COURT AT CALCUTTA APPELLATE JURISDICTION SUPPLEMENTARY LIST TO THE COMBINED MONTHLY LIST OF CASES ON AND FROM , MONDAY, THE 5TH JUNE, 2017, FOR HEARING ON MONDAY, THE 5TH JUNE, 2017. INDEX SL. BENCHES COURT TIME PAGE NO. ROOM NO. NO. 1. THE HON’BLE ACTING CHIEF JUSTICE NISHITA MHATRE 1 AND (DB – I) THE HON’BLE JUSTICE TAPABRATA CHAKRABORTY THE HON’BLE JUSTICE PATHERYA ON AND 2. AND 8 FROM THE HON’BLE JUSTICE SUBRATA TALUKDAR 05.06.2017 FROM 10.30 A.M. TILL 1.15 P.M. ON AND 3. THE HON’BLE JUSTICE SUBRATA TALUKDAR 29 FROM 05.06.2017 FROM 2.00 P.M. ----------------------------------------------------------------------- --------- *********************************************************************** ********* 05/06/2017 COURT NO. 1 FIRST FLOOR THE HON'BLE ACTING CHIEF JUSTICE NISHITA MHATRE AND HON'BLE JUSTICE TAPABRATA CHAKRABORTY *********************************************************************** ********* (DB – I) ON AND FROM MONDAY, THE 10TH APRIL, 2017 - Writ Appeals relating to Service (Gr.-VI); WRIT APPEALS RELATING TO (GR.-IX) RESIDUARY; CONTEMPT SEC. 19(A), SEC. 27 OF ELECTRICITY REG. PIL, Matters under Article 226/227 of the Constitution of India relating to Tribunals under Art. 323A and applications thereto; Writ Appeals not assigned to any other bench. And On and from Monday, the 5th June 2017 to Friday, the 9th June, 2017 (Both days inclusive) – will take, in addition to their own list and determination, urgent matters relating to the list and determination of the Division Bench comprising Hon’ble Justice Sanjib Banerjee and Hon’ble Justice Siddhartha Chattopadhyay. NOTE : On and from 9.1.2017, Tribunal motions, applications and hearing will be taken up during the entire week and other matters will be taken up in the following week. -

Padma Vibhushan * * the Padma Vibhushan Is the Second-Highest Civilian Award of the Republic of India , Proceeded by Bharat Ratna and Followed by Padma Bhushan

TRY -- TRUE -- TRUST NUMBER ONE SITE FOR COMPETITIVE EXAM SELF LEARNING AT ANY TIME ANY WHERE * * Padma Vibhushan * * The Padma Vibhushan is the second-highest civilian award of the Republic of India , proceeded by Bharat Ratna and followed by Padma Bhushan . Instituted on 2 January 1954, the award is given for "exceptional and distinguished service", without distinction of race, occupation & position. Year Recipient Field State / Country Satyendra Nath Bose Literature & Education West Bengal Nandalal Bose Arts West Bengal Zakir Husain Public Affairs Andhra Pradesh 1954 Balasaheb Gangadhar Kher Public Affairs Maharashtra V. K. Krishna Menon Public Affairs Kerala Jigme Dorji Wangchuck Public Affairs Bhutan Dhondo Keshav Karve Literature & Education Maharashtra 1955 J. R. D. Tata Trade & Industry Maharashtra Fazal Ali Public Affairs Bihar 1956 Jankibai Bajaj Social Work Madhya Pradesh Chandulal Madhavlal Trivedi Public Affairs Madhya Pradesh Ghanshyam Das Birla Trade & Industry Rajashtan 1957 Sri Prakasa Public Affairs Andhra Pradesh M. C. Setalvad Public Affairs Maharashtra John Mathai Literature & Education Kerala 1959 Gaganvihari Lallubhai Mehta Social Work Maharashtra Radhabinod Pal Public Affairs West Bengal 1960 Naryana Raghvan Pillai Public Affairs Tamil Nadu H. V. R. Iyengar Civil Service Tamil Nadu 1962 Padmaja Naidu Public Affairs Andhra Pradesh Vijaya Lakshmi Pandit Civil Service Uttar Pradesh A. Lakshmanaswami Mudaliar Medicine Tamil Nadu 1963 Hari Vinayak Pataskar Public Affairs Maharashtra Suniti Kumar Chatterji Literature -

Address of Hon'ble President of India

SPEECH BY THE PRESIDENT OF INDIA, SHRI PRANAB MUKHERJEE AT THE INAUGURATION OF 100TH SESSION OF INDIAN SCIENCE CONGRESS Kolkata, West Bengal : 03-01-2013 At the outset, I wish the participants to the Centenary session of Indian Science Congress and the people of the Nation, a purposeful and productive New Year. My warmest congratulations to the Indian Science Congress on the occasion of the celebration of their centenary. The Prime Minister of India generally inaugurates the annual sessions of Indian Science Congress. In the current year, the Association has elected the Prime Minister as its General President. I congratulate Dr. Manmohan Singh for being elected as the General President of Indian Science Congress in this historic year. It is a befitting honour. I can from personal experience vouchsafe the abiding faith of Dr. Manmohan Singh on education, science and technology. The good performance of science and technology sector in the recent years, I believe, owes greatly to the generous government support for S&T catalysed by the Prime Minister. Ladies and Gentlemen: 2. I am an alumnus of Calcutta University. Naturally, I am delighted to participate in a function co-organized by Calcutta University. As an alumnus, I fondly remember defining role of this university and Sir Asutosh Mukherjee in nurturing the Indian Science Congress in the early years. Kolkata has remained historically a city of culture, of knowledge. All Nobel Prizes 1 awarded for work from India are somehow linked to the city of Kolkata. Sir Ronald Ross carried out his pioneering research on Malaria in this city for which he was awarded the Nobel Prize in 1902. -

SATYENDRA NATH BOSE Santimay Chatterjee Enakshi Chatterjee

SATYENDRA NATH BOSE Santimay Chatterjee Enakshi Chatterjee Contents Preface 1. The Background 2. The Formative-Years (1894-1914) 3. Early Career (1915-1920) 4. The Young Intellectuals 5. First Visit to Europe (1921-1926) 6. Stay at Dacca (1927-1945) 7. Bose at Calcutta (1945-1956) 8. At Santiniketan (1956-1958) 9. The Unconventional Scientist 10. Science through the Mother Tongue 11. The Last Years (1959-1974) 12. The Complete Man References Appendix I List or published papers by S.N. Bose II The Classical Determinism and the Quantum Theory Preface The role of a father figure of Indian science was more or less thrust upon Professor Bose, yet he was grossly misunderstood by many. The image of the idle genius who wasted his powers in intellectual small talk has persisted. It is the task of the biographer to find out if such an image was based on justifiable assumptions. Between the admirers and the detractors, the legend has grown, and the man has been somewhat cast in the background. Bose is perhaps still too close to us historically for a proper perspective. We have made an attempt to show him against the changing times when science was making rapid strides in India, and white doing so other personalities have been drawn into the canvas. We realise, however, the inadequacy of our attempt for Bose was a very complex personality. It would have taken years of research and labour to collect and sort all the materials which, however, are not easily obtainable. Bose’s habit of not keeping any record, letters or diary has further handicapped us; hence some of the information could not be verified.