Shelter from the Storm: Somali Migrant Networks in Uganda Between

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CV Chrys J. Kikwabanga

CARRICULUM VITAE ADDRESS: 9-11 CABANA CRESCENT, BUGONGA. P.O. Box 535 ENTEBBE UGANDA. Email Address: [email protected], [email protected], [email protected]. Telephone: +256772505078, +256757717617 Surname: KIKWABANGA Other Names: CHRYSOSTOM JONES Date of Birth: 14th May 1952. Place of Birth: Nyenga Uganda. Nationality: Ugandan Status: Married to Annet Ndagire Namusoke (with four 4 Children) Passport: Ugandan (B1698601) Valid Till 03 August 2028 Retired Captain, Airline Transport Pilot (Aeroplanes) Flying Experience and Previous Employment: 43 Years Flying Worldwide, Passenger and Cargo Aircraft Types: Cessna150, Cessna172, Cessna 310, Cessna 402 & King Air BE100 Training (1973 – 1975) Captain Cessna 206, DHC-6, Uganda Airlines (1977 – 1979) Co-pilot Fokker F-27, Uganda Airlines (1980 – 1985) Co-pilot Boeing B707, Uganda Airlines (1986 – 1990) Co-pilot B707 African Express International (1991 – 1992) Captain Boeing B707, Dairo Air Services Cargo (1993 – 1998). Captain McDonald Douglas DC10-30 Series. Das Air Cargo (1999 – 2007) Captain MacDonald Douglas DC-9-MD-80Series. Air Uganda (2008 – 2009) Captain Bombardier Canadian Regional Jet 100/200. Air Uganda (2010 – 2014) Captain Bombardier CRJ900/1000. Arik Air (2015 – 2017) Total Flying Hours: 22500hrs, B707 - 5400hrs - Pilot in Command (1992-1999) DC10 – 6500hrs – Pilot in Command (1999-2007) MD 87 – 1200hrs – Pilot in Command (2008-2012) CRJ 100/200 – 2000hrs – Pilot In command (2011- 2014) CRJ 900/1000 – 1850hrs Pilot in Command (2015 – 2017) Others – 5550hrs – (Includes Dual/Training & Co-pilot Hrs) Responsibilities Held: Line Captain. Directly responsible for, and being final authority as to the operation of the aircraft Ensure that aircraft is safe to fly Working as part of a team alongside the First Officer and Cabin Crew to ensure a fast, safe, smooth and memorable flight for passengers. -

Ordonnance Instituant Des Mesures À L'encontre De Personnes

946.203 Ordonnance instituant des mesures à l’encontre de personnes et entités liées à Oussama ben Laden, au groupe «Al-Qaïda» ou aux Taliban1 du 2 octobre 2000 (Etat le 23 janvier 2007) Le Conseil fédéral suisse, vu l’art. 2 de la loi fédérale du 22 mars 2002 sur l’application de sanctions internationales (loi sur les embargos)2,3 arrête: Art. 14 Interdiction de fournir de l’équipement militaire et des biens similaires 1 La fourniture, la vente et le courtage d’armements de toute sorte, y compris d’armes et de munitions, de véhicules et d’équipement militaires, de matériels para- militaires de même que leurs accessoires et pièces de rechange aux personnes physi- ques et morales, aux groupes ou aux entités cités à l’annexe 2 sont interdits.5 2 ...6 3 La fourniture, la vente et le courtage de conseils techniques et de moyens d’assistance ou d’entraînement liés aux activités militaires aux personnes physiques et morales, aux groupes ou aux entités cités à l’annexe 2 sont interdits.7 4 Les al. 1 et 3 ne s’appliquent que dans la mesure où la loi du 13 décembre 1996 sur le contrôle des biens8, la loi fédérale du 13 décembre 1996 sur le matériel de guerre9 ainsi que leurs ordonnances d’application ne sont pas applicables. Art. 1a10 Art. 211 RO 2000 2642 1 Nouvelle teneur selon le ch. I de l’O du 1er mai 2002 (RO 2002 1646). 2 RS 946.231 3 Nouvelle teneur selon le ch. I de l’O du 30 oct. -

The Path of Somali Refugees Into Exile Exile Into Refugees Somali of Path the Joëlle Moret, Simone Baglioni, Denise Efionayi-Mäder

The Path of Somalis have been leaving their country for the last fifteen years, fleeing civil war, difficult economic conditions, drought and famine, and now constitute one of the largest diasporas in the world. Somali Refugees into Exile A Comparative Analysis of Secondary Movements Organized in the framework of collaboration between UNHCR and and Policy Responses different countries, this research focuses on the secondary movements of Somali refugees. It was carried out as a multi-sited project in the following countries: Djibouti, Egypt, Ethiopia, Kenya, the Netherlands, Efionayi-Mäder Denise Baglioni, Simone Moret, Joëlle South Africa, Switzerland and Yemen. The report provides a detailed insight into the movements of Somali refugees that is, their trajectories, the different stages in their migra- tion history and their underlying motivations. It also gives a compara- tive overview of different protection regimes and practices. Authors: Joëlle Moret is a social anthropologist and scientific collaborator at the SFM. Simone Baglioni is a political scientist and scientific collaborator at the SFM and at the University Bocconi in Italy. Denise Efionayi-Mäder is a sociologist and co-director of the SFM. ISBN-10: 2-940379-00-9 ISBN-13: 978-2-940379-00-2 The Path of Somali Refugees into Exile Exile into Refugees Somali of Path The Joëlle Moret, Simone Baglioni, Denise Efionayi-Mäder � � SFM Studies 46 SFM Studies 46 Studies SFM � SFM Studies 46 Joëlle Moret Simone Baglioni Denise Efionayi-Mäder The Path of Somali Refugees into Exile A Comparative -

Identity Documents and Travel Documents (January 2000 - June 2004) Research Directorate, Immigration and Refugee Board, Ottawa

Home > Research > Responses to Information Requests RESPONSES TO INFORMATION REQUESTS (RIRs) New Search | About RIRs | Help 29 July 2004 SOM42806.E Somalia: Identity documents and travel documents (January 2000 - June 2004) Research Directorate, Immigration and Refugee Board, Ottawa Identity Documents Information on Somali identity documents was scarce among the sources consulted by the Research Directorate. According to a report prepared by the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) and the Austrian Centre for Country of Origin and Asylum research and Documentation (ACCORD) on the Seventh European Country of Origin Information Seminar, which was held in Berlin, Germany, from 11-12 June 2001, identity documents were not being issued anywhere in Somalia in 2001 (UNHCR/ACCORD 11-12 June 2001, 146). In 2001, Somaliland authorities were, however, issuing drivers' licenses, which could be used to establish the identity of those who held them (ibid.). In May 2004, the Home Office of the United Kingdom (UK) issued an "Operational Guidance Note" on Somalia, in which it stated that it is impossible to verify the authenticity of any documents presented by Somalis who apply for asylum in the UK because there is no central government or authority in Somalia that keeps official records of the population or of the issuance of such documents to enable verification (Sec. 5.3.1). Additionally, the official records that had been kept prior to the collapse of the government were destroyed during the civil war (UK May 2004, Sec. 5.3.1). While the UK Home Office acknowledged that "[s]ome local administrations such as Somaliland and the TNG [Transitional National Government] authorities issue documents (birth certificates, passports etc.), [it also pointed out that] these are not issued under any internationally recognised authority and are not verifiable" (ibid.). -

Immigration and Refugee Board of Canada Page 1 of 4

Responses to Information Requests - Immigration and Refugee Board of Canada Page 1 of 4 Immigration and Refugee Board of Canada Home > Research Program > Responses to Information Requests Responses to Information Requests Responses to Information Requests (RIR) respond to focused Requests for Information that are submitted to the Research Directorate in the course of the refugee protection determination process. The database contains a seven- year archive of English and French RIRs. Earlier RIRs may be found on the UNHCR's Refworld website. Please note that some RIRs have attachments which are not electronically accessible. To obtain a PDF copy of an RIR attachment, please email the Knowledge and Information Management Unit. 17 March 2016 SOM105248.E Somalia: Identification documents, including national identity cards, passports, driver's licenses, and any other document required to access government services; information on the issuing agencies and the requirements to obtain documents (2013-July 2015) Research Directorate, Immigration and Refugee Board of Canada, Ottawa 1. Accessibility of Official Documentation in Somalia According to the US Department of State's Country Reciprocity Schedule for Somalia, "[t]here are no circumstances under which immigrant visa applicants can reasonably be expected to recover original documents held by the former Government of Somalia" due to a lack of "competent civil authority to issue civil documents" and the destruction of most records over the course of the civil war (US n.d.). Other sources report that the Somali government is issuing passports and identity cards under the authority of the Benadir administration in Mogadishu (Lawyer 24 July 2015; EU Aug. 2014, 40) in the district of Cabulcasiis (ibid.). -

Russian Federation

September 1997 Vol. 9, No. 10 (D) RUSSIAN FEDERATION MOSCOW: OPEN SEASON, CLOSED CITY SUMMARY.................................................................................................................................................................................2 RECOMMENDATIONS.............................................................................................................................................................3 INTRODUCTION .......................................................................................................................................................................5 MOSCOW=S REGISTRATION AND REFUGEE POLICY: A STATE WITHIN A STATE....................................................7 Registration for Temporary Stays..................................................................................................................................7 Registration for Permanent Residence...........................................................................................................................9 Evaluation....................................................................................................................................................................11 THE IMPACT OF REGISTRATION ON REFUGEES AND INTERNALLY DISPLACED PERSONS ...............................13 Introduction .................................................................................................................................................................13 Moscow Refugee Regulations: A -

Revival of Uganda's National Carrier – Feasibility Study

Feasibility Report: National Airline THE REPUBLIC OF UGANDA National Planning Authority DEVELOPING MIDDLE INCOME HOUSING SERVICE AND SERVICE DELIVERY STANDARDS FOR UGANDA National Planning Authority Plot 15B, Clement Hill Road P.O. Box 21434, KampalaNational – Uganda Planning Authority Tel. +256-414- 250214/250229 Plot 15B, Clement Hill Road Fax. +256-414- 250213 REVIVAL OF UGANDA’S NATIONAL Email: [email protected] P.O. Box 21434, Kampala – Uganda Uganda THE REPUBLIC OF UGANDA Website: www.npa.ug Tel. +256-414- 250214/250229 Fax. +256-414- 250213 CARRIER THE REPUBLIC OF UGANDA Email: [email protected] Website: www.npa.ug National Planning Authority FEASIBILITY STUDY DEVELOPING MIDDLE INCOME HOUSING THE REPUBLIC OF UGANDA SERVICE AND SERVICE DELIVERY A PEC PAPER ON THE REVIVAL OF UGANDA’S NATIONAL CARRIER FEASIBILITY STUDY i STANDARDS FOR UGANDA National Planning Authority DEVELOPING MIDDLE INCOME HOUSING SERVICE AND SERVICE DELIVERY STANDARDS FOR UGANDA National Planning Authority Plot 15B, Clement Hill Road P.O. Box 21434, Kampala – Uganda Tel. +256-414- 250214/250229 Fax. +256-414- 250213 Email: [email protected] Uganda THE REPUBLIC OF UGANDA Website: www.npa.ug National Planning Authority Plot 15B, Clement Hill Road P.O. Box 21434, Kampala – Uganda Tel. +256-414- 250214/250229 Fax. +256-414- 250213 Email: [email protected] Uganda THE REPUBLIC OF UGANDA Website: www.npa.ug Feasibility Report: National Airline Table of Contents List of Tables ����������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������iii -

Uganda Airlinesapril 23.Indd

22 NEW VISION, Tuesday, April 23, 2019 ADVERTISER SUPPLEMENT A FUNCTIONAL NATIONAL AIRLINE HAS POTENTIAL TO IMPROVE THE BALANCE OF TRADE By Owen Wagabaza Current prices are averaging n 2016, during the $330 for economy class on this Independence Day Why was it important to route, after commencement of celebrations in Kiyunga, operations by RwandAir. Luuka district, President This demonstrates the Yoweri Museveni competitive power of having a announced the revival strong local airline to ensure a of Uganda Airlines after level playing field and proper I15 years on the sidelines. pricing for the consumer. According to Dr Joseph revive Uganda Airlines? The drop of air fares to Muvawala, the executive and from Entebbe will lead director of the National to significant savings for Planning Authority, the airline passengers. There will be a is in line with Uganda’s Vision reduction of dominance of 2040, which sets the long-term foreign operators, which bears aspirations of transforming unfair influence on the cost of Uganda from predominantly air travel. peasant to a modern and There will also be a balance prosperous country within 30 of aviation opportunities years. arising from mutually beneficial The idea was formulated in bilateral agreements and the First National Development benefits only attributable to Plan and the Second National national airlines. Development Plan where the Currently, only foreign airline is highlighted as one of airlines benefit from Uganda’s the flagship projects expected aviation market with revenue to drive Uganda towards -

Prior Compliance List of Aircraft Operators Specifying the Administering Member State for Each Aircraft Operator – June 2014

Prior compliance list of aircraft operators specifying the administering Member State for each aircraft operator – June 2014 Inclusion in the prior compliance list allows aircraft operators to know which Member State will most likely be attributed to them as their administering Member State so they can get in contact with the competent authority of that Member State to discuss the requirements and the next steps. Due to a number of reasons, and especially because a number of aircraft operators use services of management companies, some of those operators have not been identified in the latest update of the EEA- wide list of aircraft operators adopted on 5 February 2014. The present version of the prior compliance list includes those aircraft operators, which have submitted their fleet lists between December 2013 and January 2014. BELGIUM CRCO Identification no. Operator Name State of the Operator 31102 ACT AIRLINES TURKEY 7649 AIRBORNE EXPRESS UNITED STATES 33612 ALLIED AIR LIMITED NIGERIA 29424 ASTRAL AVIATION LTD KENYA 31416 AVIA TRAFFIC COMPANY TAJIKISTAN 30020 AVIASTAR-TU CO. RUSSIAN FEDERATION 40259 BRAVO CARGO UNITED ARAB EMIRATES 908 BRUSSELS AIRLINES BELGIUM 25996 CAIRO AVIATION EGYPT 4369 CAL CARGO AIRLINES ISRAEL 29517 CAPITAL AVTN SRVCS NETHERLANDS 39758 CHALLENGER AERO PHILIPPINES f11336 CORPORATE WINGS LLC UNITED STATES 32909 CRESAIR INC UNITED STATES 32432 EGYPTAIR CARGO EGYPT f12977 EXCELLENT INVESTMENT UNITED STATES LLC 32486 FAYARD ENTERPRISES UNITED STATES f11102 FedEx Express Corporate UNITED STATES Aviation 13457 Flying -

Airlines List in Outside

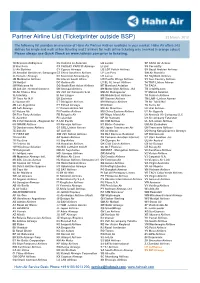

Partner Airline List (Ticketprinter outside BSP) 23 March, 2012 The following list provides an overview of Hahn Air Partner Airlines available in your market. Hahn Air offers 243 airlines for single and multi airline ticketing and 2 airlines for multi airline ticketing only (marked in orange colour). Please always use Quick Check on www.hahnair.com prior to ticketing. 1X Branson AirExpress CU Cubana de Aviacion LG Luxair SP SATA Air Acores 2I Star Perú CX CATHAY PACIFIC Airways LI Liat SS Corsairfly 2J Air Burkina CY Cyprus Airways LO LOT Polish Airlines SV Saudi Arabian Airlines 2K AeroGal Aerolineas Galapagos CZ China Southern Airlines LP Lan Peru SW Air Namibia 2L Helvetic Airways D2 Severstal Aircompany LR Lacsa SX SkyWork Airlines 2M Moldavian Airlines D6 Interair South Africa LW Pacific Wings Airlines SY Sun Country Airlines 2N Nextjet DC Golden Air LY EL AL Israel Airlines T4 TRIP Linhas Aéreas 2W Welcome Air DG South East Asian Airlines M7 Marsland Aviation TA TACA 3B Job Air - Central Connect DN Senegal Airlines M9 Motor Sich Airlines JSC TB Jetairfly.com 3E Air Choice One DV JSC Air Company Scat MD Air Madagascar TF Malmö Aviation 3L InterSky EI Aer Lingus ME Middle East Airlines TK Turkish Airlines 3P Tiara Air N.V. EK Emirates MF Xiamen Airlines TM LAM - Linhas Aereas 4J Somon Air ET Ethiopian Airlines MH Malaysia Airlines TN Air Tahiti Nui 4M Lan Argentina EY Etihad Airways MI SilkAir TU Tunis Air 4Q Safi Airways F7 Darwin Airline SA MK Air Mauritius U6 Ural Airlines 5C Nature Air F9 Frontier Airlines MU China Eastern Airlines -

Visionary Africa - Art at Work – Kampala

VISIONARY AFRICA - ART AT WORK – KAMPALA Conference How art and architecture can make city development inclusive and sustainable Programme Tuesday September 18, 2012 9:00-17:00 Kampala City Hall, Kampala (70 participants, see next page) Introduction As Uganda gears itself for significant future growth in the next decade, the city of Kampala assesses the ensuing economic, social and cultural changes within the city. To discuss the challenges and choices Kampala and East African Capitals face, an unprecedented inclusive debate is organized among city stakeholders of the region together with international experts, on the city’s urban development and the role of art and architecture in it . The morning session will address the role and responsibilities of authorities, urban planners, architects, and arts managers in the development of a strategic vision for their city and in the planning process; and action and tools at their disposal to guarantee a sustainable and inclusive development of African cities. The afternoon session will address initiatives needed so that authorities, urban planners, architects and arts managers can have a decisive role in the sustainable and inclusive development of their city. Objectives The overall objective of the conference is twofold: - a Declaration of Kampala , setting a framework for the role of art and architecture in the development of East Africa’s capitals including Recommendations for Kampala and the other capitals of the region. - a proposal for a permanent mechanism towards inclusive and sustainable urban development among capital cities in the East African region. Each speaker will be asked to close his/her presentation with a statement towards these objectives. -

Somalia Passport Application at the Somali Embassy in Brussels

Query response Somalia: Passport application at the Somali Embassy in Brussels • What are the application procedures at the embassy? • What do applicants have to bring with them when applying for a passport at the embassy? • How much does it cost to apply for a passport at the embassy? • How long does it take to get a passport? • Do applicants have to appear in person both when submitting the application and when retrieving the passport? • What about minor applicants, with or without parents in Norway? • Is it possible to book an appointment in advance? Introduction This query response attempts to answer a number of practical questions relating to passport application at the Somali Embassy in Brussels. The procedures for passport application at Somali embassies appear to be fairly similar (IND 2019). When Landinfo began investigating this subject in January 2019, the embassy in Brussels was the nearest Somali embassy with authority to accept passport applications. Since 15 April 2019, it has also been possible to apply for a passport at the Somali Embassy in Berlin (Norwegian Embassy in Nairobi, email 2019). The embassies’ services are not limited to Somalis residing in the countries for which the embassies have consular responsibility, i.e. Somalis in Norway can choose the embassy they want to apply at (IND 2019).1 All passport applications are sent to the main office of the Somali Immigration and Naturalization Directorate (IND) for checking, approval and issuance. 1 The third Somali embassy in Europe with authority to accept passport applications is the embassy in Rome (National ID Centre 2019).