Lessons from the Triassic-Jurassic Newark Basin of Eastern North America

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Preliminary Catalog of the Sedimentary Basins of the United States

Preliminary Catalog of the Sedimentary Basins of the United States By James L. Coleman, Jr., and Steven M. Cahan Open-File Report 2012–1111 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey U.S. Department of the Interior KEN SALAZAR, Secretary U.S. Geological Survey Marcia K. McNutt, Director U.S. Geological Survey, Reston, Virginia: 2012 For more information on the USGS—the Federal source for science about the Earth, its natural and living resources, natural hazards, and the environment, visit http://www.usgs.gov or call 1–888–ASK–USGS. For an overview of USGS information products, including maps, imagery, and publications, visit http://www.usgs.gov/pubprod To order this and other USGS information products, visit http://store.usgs.gov Any use of trade, firm, or product names is for descriptive purposes only and does not imply endorsement by the U.S. Government. Although this information product, for the most part, is in the public domain, it also may contain copyrighted materials as noted in the text. Permission to reproduce copyrighted items must be secured from the copyright owner. Suggested citation: Coleman, J.L., Jr., and Cahan, S.M., 2012, Preliminary catalog of the sedimentary basins of the United States: U.S. Geological Survey Open-File Report 2012–1111, 27 p. (plus 4 figures and 1 table available as separate files) Available online at http://pubs.usgs.gov/of/2012/1111/. iii Contents Abstract ...........................................................................................................................................................1 -

Lesson 3 Forces That Build the Land Main Idea

Lesson 3 Forces That Build the Land Main Idea Many landforms result from changes and movements in Earth’s crust. Objectives Identify types of landforms and the processes that form them. Describe what happens when an earthquake occurs. Vocabulary fault focus aftershock seismic wave epicenter seismograph magnitude vent What forces change Earth’s crust? At transform boundaries, the pieces of rock rub together in a force called shearing, like the blades of a pair of scissors, causing the rock to break. At convergent boundaries, plates collide and this force is called compression, squeezing the rock together. At divergent boundaries, plates separate causing tension, making the crust longer and thinner eventually breaking and creating a fault. Faults are usually located along the boundaries between tectonic plates. Three Kinds of Faults Shearing forms strike-slip faults. Tension forms normal faults. The rock above the fault moves down. Compression forms reverse faults. The rock above the fault moves up. Uplifted Landforms Folded mountains are mostly made up of rock layers folded by being squeezed together. Fault-block mountains are made by huge, tilted blocks of rock separated from the surrounding rock by faults. The Colorado Plateau was formed when rock layers were pushed upward. The Colorado River eventually formed the Grand Canyon. Quick Check Infer Why are faults often produced along plate boundaries? Forces act on the crust most directly at plate boundaries, because these locations are where plates are moving, relative to each other. Critical Thinking Why do some mountains form as folded mountains and others form as fault-block mountains? Compression forces form folded mountains, and tension forms fault- block mountains. -

Potential On-Shore and Off-Shore Reservoirs for CO2 Sequestration in Central Atlantic Magmatic Province Basalts

Potential on-shore and off-shore reservoirs for CO2 sequestration in Central Atlantic magmatic province basalts David S. Goldberga, Dennis V. Kenta,b,1, and Paul E. Olsena aLamont-Doherty Earth Observatory, 61 Route 9W, Palisades, NY 10964; and bEarth and Planetary Sciences, Rutgers University, Piscataway, NJ 08854. Contributed by Dennis V. Kent, November 30, 2009 (sent for review October 16, 2009) Identifying locations for secure sequestration of CO2 in geological seafloor (16) may offer potential solutions to these additional formations is one of our most pressing global scientific problems. issues that are more problematic on land. Deep-sea aquifers Injection into basalt formations provides unique and significant are fully saturated with seawater and typically capped by imper- advantages over other potential geological storage options, includ- meable sediments. The likelihood of postinjection leakage of ing large potential storage volumes and permanent fixation of car- CO2 to the seafloor is therefore low, reducing the potential bon by mineralization. The Central Atlantic Magmatic Prov- impact on natural and human ecosystems (8). Long after CO2 ince basalt flows along the eastern seaboard of the United States injection, the consequences of laterally displaced formation water may provide large and secure storage reservoirs both onshore and to distant locations and ultimately into the ocean, whether by offshore. Sites in the South Georgia basin, the New York Bight engineered or natural outflow systems, are benign. For more than basin, and the Sandy Hook basin offer promising basalt-hosted a decade, subseabed CO2 sequestration has been successfully reservoirs with considerable potential for CO2 sequestration due conducted at >600 m depth in the Utsira Formation as part of to their proximity to major metropolitan centers, and thus to large the Norweigan Sleipner project (17). -

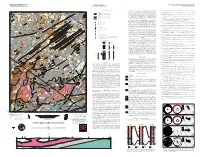

Bedrock Geologic Map of the Monmouth Junction Quadrangle, Water Resources Management U.S

DEPARTMENT OF ENVIRONMENTAL PROTECTION Prepared in cooperation with the BEDROCK GEOLOGIC MAP OF THE MONMOUTH JUNCTION QUADRANGLE, WATER RESOURCES MANAGEMENT U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY SOMERSET, MIDDLESEX, AND MERCER COUNTIES, NEW JERSEY NEW JERSEY GEOLOGICAL AND WATER SURVEY NATIONAL GEOLOGIC MAPPING PROGRAM GEOLOGICAL MAP SERIES GMS 18-4 Cedar EXPLANATION OF MAP SYMBOLS cycle; lake level rises creating a stable deep lake environment followed by a fall in water level leading to complete Cardozo, N., and Allmendinger, R. W., 2013, Spherical projections with OSXStereonet: Computers & Geosciences, v. 51, p. 193 - 205, doi: 74°37'30" 35' Hill Cem 32'30" 74°30' 5 000m 5 5 desiccation of the lake. Within the Passaic Formation, organic-rick black and gray beds mark the deep lake 10.1016/j.cageo.2012.07.021. 32 E 33 34 535 536 537 538 539 540 541 490 000 FEET 542 40°30' 40°30' period, purple beds mark a shallower, slightly less organic-rich lake, and red beds mark a shallow oxygenated 6 Contacts 100 M Mettler lake in which most organic matter was oxidized. Olsen and others (1996) described the next longer cycle as the Christopher, R. A., 1979, Normapolles and triporate pollen assemblages from the Raritan and Magothy formations (Upper Cretaceous) of New 6 A 100 I 10 N Identity and existance certain, location accurate short modulating cycle, which is made up of five Van Houten cycles. The still longer in duration McLaughlin cycles Jersey: Palynology, v. 3, p. 73-121. S T 44 000m MWEL L RD 0 contain four short modulating cycles or 20 Van Houten cycles (figure 1). -

Regional Geology of the Scotian Basin

REGIONAL GEOLOGY OF THE SCOTIAN BASIN David E. Brown, CNSOPB, 2008 INTRODUCTION The Scotian Basin is a classic passive, mostly non-volcanic, conjugate margin. It represents over 250 million years of continuous sedimentation recording the region's dynamic geological history from the initial opening of the Atlantic Ocean to the recent post-glacial deposition. The basin is located on the northeastern flank of the Appalachian Orogen and covers an area of approximately 300,000 km2 with an estimated maximum sediment thickness of about 24 kilometers. The continental-size drainage system of the paleo-St. Lawrence River provided a continuous supply of sediments that accumulated in a number of complex, interconnected subbasins. The basin's stratigraphic succession contains early synrift continental, postrift carbonate margin, fluvial-deltaic-lacustrine, shallow marine and deepwater depositional systems. PRERIFT The Scotian Basin is located offshore Nova Scotia where it extends for 1200 km from the Yarmouth Arch / United States border in the southwest to the Avalon Uplift on the Grand Banks of Newfoundland in the northeast (Figure 1). With an average breadth of 250 km, the total area of the basin is approximately 300,000 km2. Half of the basin lies on the present-day continental shelf in water depths less than 200 m with the other half on the continental slope in water depths from 200 to >4000 m. The Scotian Basin formed on a passive continental margin that developed after North America rifted and separated from the African continent during the breakup of Pangea (Figure 2). Its tectonic elements consist of a series of platforms and depocentres separated by basement ridges and/or major basement faults. -

Part 3: Normal Faults and Extensional Tectonics

12.113 Structural Geology Part 3: Normal faults and extensional tectonics Fall 2005 Contents 1 Reading assignment 1 2 Growth strata 1 3 Models of extensional faults 2 3.1 Listric faults . 2 3.2 Planar, rotating fault arrays . 2 3.3 Stratigraphic signature of normal faults and extension . 2 3.4 Core complexes . 6 4 Slides 7 1 Reading assignment Read Chapter 5. 2 Growth strata Although not particular to normal faults, relative uplift and subsidence on either side of a surface breaking fault leads to predictable patterns of erosion and sedi mentation. Sediments will fill the available space created by slip on a fault. Not only do the characteristic patterns of stratal thickening or thinning tell you about the 1 Figure 1: Model for a simple, planar fault style of faulting, but by dating the sediments, you can tell the age of the fault (since sediments were deposited during faulting) as well as the slip rates on the fault. 3 Models of extensional faults The simplest model of a normal fault is a planar fault that does not change its dip with depth. Such a fault does not accommodate much extension. (Figure 1) 3.1 Listric faults A listric fault is a fault which shallows with depth. Compared to a simple planar model, such a fault accommodates a considerably greater amount of extension for the same amount of slip. Characteristics of listric faults are that, in order to maintain geometric compatibility, beds in the hanging wall have to rotate and dip towards the fault. Commonly, listric faults involve a number of en echelon faults that sole into a lowangle master detachment. -

THE JOURNAL of GEOLOGY March 1990

VOLUME 98 NUMBER 2 THE JOURNAL OF GEOLOGY March 1990 QUANTITATIVE FILLING MODEL FOR CONTINENTAL EXTENSIONAL BASINS WITH APPLICATIONS TO EARLY MESOZOIC RIFTS OF EASTERN NORTH AMERICA' ROY W. SCHLISCHE AND PAUL E. OLSEN Department of Geological Sciences and Lamont-Doherty Geological Observatory of Columbia University, Palisades, New York 10964 ABSTRACT In many half-graben, strata progressively onlap the hanging wall block of the basins, indicating that both the basins and their depositional surface areas were growing in size through time. Based on these con- straints, we have constructed a quantitative model for the stratigraphic evolution of extensional basins with the simplifying assumptions of constant volume input of sediments and water per unit time, as well as a uniform subsidence rate and a fixed outlet level. The model predicts (1) a transition from fluvial to lacustrine deposition, (2) systematically decreasing accumulation rates in lacustrine strata, and (3) a rapid increase in lake depth after the onset of lacustrine deposition, followed by a systematic decrease. When parameterized for the early Mesozoic basins of eastern North America, the model's predictions match trends observed in late Triassic-age rocks. Significant deviations from the model's predictions occur in Early Jurassic-age strata, in which markedly higher accumulation rates and greater lake depths point to an increased extension rate that led to increased asymmetry in these half-graben. The model makes it possible to extract from the sedimentary record those events in the history of an extensional basin that are due solely to the filling of a basin growing in size through time and those that are due to changes in tectonics, climate, or sediment and water budgets. -

2020 Natural Resources Inventory

2020 NATURAL RESOURCES INVENTORY TOWNSHIP OF MONTGOMERY SOMERSET COUNTY, NEW JERSEY Prepared By: Tara Kenyon, AICP/PP Principal NJ License #33L100631400 Table of Contents EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ............................................................................................................................................... 5 AGRICULTURE ............................................................................................................................................................. 7 AGRICULTURAL INDUSTRY IN AND AROUND MONTGOMERY TOWNSHIP ...................................................... 7 REGULATIONS AND PROGRAMS RELATED TO AGRICULTURE ...................................................................... 11 HEALTH IMPACTS OF AGRICULTURAL AVAILABILITY AND LOSS TO HUMANS, PLANTS AND ANIMALS .... 14 HOW IS MONTGOMERY TOWNSHIP WORKING TO SUSTAIN AND ENHANCE AGRICULTURE? ................... 16 RECOMMENDATIONS AND POTENTIAL PROJECTS .......................................................................................... 18 CITATIONS ............................................................................................................................................................. 19 AIR QUALITY .............................................................................................................................................................. 21 CHARACTERISTICS OF AIR .................................................................................................................................. 21 -

On Cape Breton Island, Nova Scotia, Canada

Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences Remnants of Early Mesozoic basalt of the Central Atlantic Magmatic Province (CAMP) on Cape Breton Island, Nova Scotia, Canada Journal: Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences Manuscript ID cjes-2016-0181.R1 Manuscript Type: Article Date Submitted by the Author: 07-Nov-2016 Complete List of Authors: White, Chris E.; Nova Scotia Department of Natural Resources Kontak, DanielDraft J.; Department of Earth Sciences, Demont, Garth J.; Nova Scotia Department of Natural Resources Archibald, Douglas; Queens University, Department of Geological Sciences Keyword: CAMP, Mesozoic, Fundy Basin, Ashfield Formation https://mc06.manuscriptcentral.com/cjes-pubs Page 1 of 48 Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences 1 Remnants of Early Mesozoic basalt of the Central Atlantic Magmatic Province (CAMP) on Cape Breton Island, Nova Scotia, Canada Chris E. White 1, Daniel J. Kontak 2, Garth J. DeMont 1, and Douglas Archibald 3 1. Nova Scotia Department of Natural Resources, Halifax, Nova Scotia, B3J 3T9, Canada 2. Department of Earth Science, Laurentian University, Sudbury, Ontario, P3E 2C6, Canada 3. Department of Geological Sciences and Geological Engineering, Queens University, Kingston, Ontario, K7L 3N6, Canada Corrected version:Draft for re-submission to CJES November 7, 2016 ABSTRACT Amygdaloidal basaltic flows of the Ashfield Formation were encountered in two drillholes in areas of positive aeromagnetic anomalies in the Carboniferous River Denys Basin in southwestern Cape Breton Island, Nova Scotia. One sample of medium-grained basalt yielded a plateau age of 201.8 ± 2.0 Ma, similar to U-Pb and 40 Ar/ 39 Ar crystallization ages from basaltic flows and dykes in the Newark Supergroup. -

From Orogeny to Rifting: When and How Does Rifting Begin? Insights from the Norwegian ‘Reactivation Phase’

EGU21-469 https://doi.org/10.5194/egusphere-egu21-469 EGU General Assembly 2021 © Author(s) 2021. This work is distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License. From orogeny to rifting: when and how does rifting begin? Insights from the Norwegian ‘reactivation phase’. Gwenn Peron-Pinvidic1,2, Per Terje Osmundsen2, Loic Fourel1, and Susanne Buiter3 1NGU - Geological Survey of Norway, 7040 Trondheim, Norway 2NTNU - Norwegian University of Science and Technology, 7491 Trondheim, Norway 3Tectonics and Geodynamics, RWTH Aachen University, 52064 Aachen, Germany Following the Wilson Cycle theory, most rifts and rifted margins around the world developed on former orogenic suture zones (Wilson, 1966). This implies that the pre-rift lithospheric configuration is heterogeneous in most cases. However, for convenience and lack of robust information, most models envisage the onset of rifting based on a homogeneously layered lithosphere (e.g. Lavier and Manatschal, 2006). In the last decade this has seen a change, thanks to the increased academic access to high-resolution, deeply imaging seismic datasets, and numerous studies have focused on the impact of inheritance on the architecture of rifts and rifted margins. The pre-rift tectonic history has often been shown as strongly influencing the subsequent rift phases (e.g. the North Sea case - Phillips et al., 2016). In the case of rifts developing on former orogens, one important question relates to the distinction between extensional structures formed during the orogenic collapse and the ones related to the proper onset of rifting. The collapse deformation is generally associated with polarity reversal along orogenic thrusts, ductile to brittle deformation and important crustal thinning with exhumation of deeply buried rocks (Andersen et al., 1994; Fossen, 2000). -

A Parametric Method to Model 3D Displacements Around Faults with Volumetric Vector Fields G

A parametric method to model 3D displacements around faults with volumetric vector fields G. Laurent, G. Caumon, A. Bouziat, M. Jessell To cite this version: G. Laurent, G. Caumon, A. Bouziat, M. Jessell. A parametric method to model 3D displace- ments around faults with volumetric vector fields. Tectonophysics, Elsevier, 2013, 590, pp.83-93. 10.1016/j.tecto.2013.01.015. hal-01301478 HAL Id: hal-01301478 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-01301478 Submitted on 23 Jul 2019 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. A parametric method to model 3D displacements around faults with volumetric vector fieldsI Gautier Laurenta,b,∗, Guillaume Caumona,b, Antoine Bouziata,b,1, Mark Jessellc, Gautier Laurenta,b,∗, Guillaume Caumona,b, Antoine Bouziata,b,1, Mark Jessellc aUniversit´ede Lorraine, CRPG UPR 2300, Vandoeuvre-l`es-Nancy,54501, France bCNRS, CRPG, UPR 2300, Vandoeuvre-l`es-Nancy, 54501, France cIRD, UR 234, GET, OMP, Universit´eToulouse III, 14 Avenue Edouard Belin, 31400 Toulouse, FRANCE Abstract This paper presents a 3D parametric fault representation for modeling the displacement field associated with faults in accordance with their geometry. The displacements are modeled in a canonical fault space where the near-field displacement is defined by a small set of parameters consisting of the maximum displacement amplitude and the profiles of attenuation in the surrounding space. -

Garlock Fault: an Intracontinental Transform Structure, Southern California

GREGORY A. DAVIS Department of Geological Sciences, University of Southern California, Los Angeles, California 90007 B. C. BURCHFIEL Department of Geology, Rice University, Houston, Texas 77001 Garlock Fault: An Intracontinental Transform Structure, Southern California ABSTRACT Sierra Nevada. Westward shifting of the north- ern block of the Garlock has probably contrib- The northeast- to east-striking Garlock fault uted to the westward bending or deflection of of southern California is a major strike-slip the San Andreas fault where the two faults fault with a left-lateral displacement of at least meet. 48 to 64 km. It is also an important physio- Many earlier workers have considered that graphic boundary since it separates along its the left-lateral Garlock fault is conjugate to length the Tehachapi-Sierra Nevada and Basin the right-lateral San Andreas fault in a regional and Range provinces of pronounced topogra- strain pattern of north-south shortening and phy to the north from the Mojave Desert east-west extension, the latter expressed in part block of more subdued topography to the as an eastward displacement of the Mojave south. Previous authors have considered the block away from the junction of the San 260-km-long fault to be terminated at its Andreas and Garlock faults. In contrast, we western and eastern ends by the northwest- regard the origin of the Garlock fault as being striking San Andreas and Death Valley fault directly related to the extensional origin of the zones, respectively. Basin and Range province in areas north of the We interpret the Garlock fault as an intra- Garlock.