Cyclic Elements in Schubert's Last Three Piano Sonatas

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Second Bassoon: Specialist, Support, Teamwork Dick Hanemaayer Amsterdam, Holland (!E Following Article first Appeared in the Dutch Magazine “De Fagot”

THE DOUBLE REED 103 Second Bassoon: Specialist, Support, Teamwork Dick Hanemaayer Amsterdam, Holland (!e following article first appeared in the Dutch magazine “De Fagot”. It is reprinted here with permission in an English translation by James Aylward. Ed.) t used to be that orchestras, when they appointed a new second bassoon, would not take the best player, but a lesser one on instruction from the !rst bassoonist: the prima donna. "e !rst bassoonist would then blame the second for everything that went wrong. It was also not uncommon that the !rst bassoonist, when Ihe made a mistake, to shake an accusatory !nger at his colleague in clear view of the conductor. Nowadays it is clear that the second bassoon is not someone who is not good enough to play !rst, but a specialist in his own right. Jos de Lange and Ronald Karten, respectively second and !rst bassoonist from the Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra explain.) BASS VOICE Jos de Lange: What makes the second bassoon more interesting over the other woodwinds is that the bassoon is the bass. In the orchestra there are usually four voices: soprano, alto, tenor and bass. All the high winds are either soprano or alto, almost never tenor. !e "rst bassoon is o#en the tenor or the alto, and the second is the bass. !e bassoons are the tenor and bass of the woodwinds. !e second bassoon is the only bass and performs an important and rewarding function. One of the tasks of the second bassoon is to control the pitch, in other words to decide how high a chord is to be played. -

Emergent Formal Functions in Schubert's Piano Sonatas

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Master's Theses Graduate School June 2020 Emergent Formal Functions in Schubert's Piano Sonatas Yiqing Ma Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_theses Part of the Musicology Commons, and the Music Theory Commons Recommended Citation Ma, Yiqing, "Emergent Formal Functions in Schubert's Piano Sonatas" (2020). LSU Master's Theses. 5156. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_theses/5156 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Master's Theses by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. EMEGERT FOMAL FUNCTIONS IN SCHUBERT’S PIANO SONATAS A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Master of Music in School of Music by Yiqing Ma B.A., University of Minnesota, 2017 August 2020 ã Copyright by Yiqing Ma, 2020. All rights reserved. ii ACKNOWLEDGMENT I first encountered Franz Schubert’s A minor piano sonata in my sophomore year by Dr. Rie Tanaka—a piece that I also performed in my first piano recital. As a psychology major at the time, I never would have thought I will pursue graduate studies in Music Theory, a discipline that my parents still do not understand what it is all about. Now, I am lucky enough to dedicate a master’s thesis on my favorite piano repertoire. -

Acoustic Guitar 2019 Graded Certificates Debut-G8 Acoustic Guitar 2019 Graded Certificates Debut-G8

Acoustic Guitar 2019 Graded Certificates debut-G8 Acoustic Guitar 2019 Graded Certificates Debut-G8 Acoustic Guitar 2019 Graded Certificates DEBUT-G5 Technical Exercise submission list Playing along to metronome is compulsory when indicated in the grade book. Exercises should commence after a 4-click metronome count in. Please ensure this is audible on the video recording. For chord exercises which are stipulated as being directed by the examiner, candidates must present all chords/voicings in all key centres. Candidates do not need to play these to click, but must be mindful of producing the chords clearly with minimal hesitancy between each. Note: Candidate should play all listed scales, arpeggios and chords in the key centres and positions shown. Debut Group A Group B Group C Scales (70 bpm) Chords Acoustic Riff 1. C major Open position chords (play all) To be played to backing track 2. E minor pentatonic 3. A minor pentatonic grade 1 Group A Group B Group C Scales (70 bpm) Chords (70 bpm) Acoustic Riff 1. C major 1. Powerchords To be played to backing track 2. A natural minor 2. Major Chords (play all) 3. E minor pentatonic 3. Minor Chords (play all) 4. A minor pentatonic 5. G major pentatonic Acoustic Guitar 2019 Graded Certificates Debut-G8 grade 2 Group A Group B Group C Scales (80 bpm) Chords (80 bpm) Acoustic Riff 1. C major 1. Powerchords To be played to backing track 2. G Major 2. Major and minor Chords 3. E natural minor (play all) 4. A natural minor 3. Minor 7th Chords (play all) 5. -

October 2015

October 2015 Bertrand Chamayou INSIDE: Ian Bostridge | Sarah Connolly Ehnes Quartet | Thomas Hampson Alina Ibragimova & Cédric Tiberghien Magdalena Kozˇená & Mitsuko Uchida Steven Isserlis | Robert Levin Sandrine Piau | Christoph Prégardien Stile Antico | Vox Luminis And many more Box Office 020 7935 2141 Online Booking www.wigmore-hall.org.uk How to Book Wigmore Hall Box Office 36 Wigmore Street, London W1U 2BP In Person 7 days a week: 10 am – 8.30 pm. Days without an evening concert 10 am – 5 pm. No advance booking in the half hour prior to a concert. Please note that the Box Office with be closed for bookings in person from Monday 27 July to Friday 4 September. By Telephone: 020 7935 2141 7 days a week: 10 am – 7 pm. Days without an evening concert 10 am – 5 pm. There is a non-refundable £3.00 administration fee for each transaction, which includes the return of your tickets by post if time permits. Online: www.wigmore-hall.org.uk 7 days a week; 24 hours a day. There is a non-refundable £2.00 administration charge. Standby Tickets Standby tickets for students, senior citizens and the unemployed are available from one hour before the performance (subject to availability) with best available seats sold at the lowest price. NB standby tickets are not available for Lunchtime and Coffee Concerts. Group Discounts Discounts of 10% are available for groups of 12 or more, subject to availability. Latecomers Latecomers will only be admitted during a suitable pause in the performance. Facilities for Disabled People full details available from 020 7935 2141 or [email protected] Wigmore Hall has been awarded the Bronze Charter Mark from Attitude is Everything TICKETS Unless otherwise stated, tickets are A–D divided into five prices ranges: BALCONY Stalls C – M W–Y Highest price T–V Stalls A – B, N – P Q–S 2nd highest price Balcony A – D N–P 2nd highest price STALLS Stalls BB, CC, Q – S C–M 3rd highest price A–B Stalls AA, T – V CC CC 4th highest price BB BB PLATFORM Stalls W – Y AAAA AAAA Lowest price This brochure is available in alternative formats. -

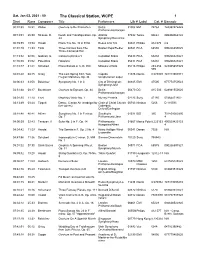

Sat, Jan 02, 2021 - 00 the Classical Station, WCPE 1 Start Runs Composer Title Performerslib # Label Cat

Sat, Jan 02, 2021 - 00 The Classical Station, WCPE 1 Start Runs Composer Title PerformersLIb # Label Cat. # Barcode 00:01:30 10:31 Weber Overture to Der Freischutz Berlin 01006 EMI 74764 724357476423 Philharmonic/Karajan 00:13:0125:39 Strauss, R. Death and Transfiguration, Op. Atlanta 07032 Telarc 80661 089408066122 24 Symphony/Runnicles 00:39:55 19:54 Haydn Piano Trio No. 36 in E flat Beaux Arts Trio 04027 Philips 432 070 n/a 01:01:1911:33 Falla Three Dances from The Boston Pops/Fiedler 04581 RCA 68550 090266855025 Three-Cornered Hat 01:13:5202:08 Gabrieli, G. Canzona prima a 5 Canadian Brass 05433 RCA 63238 090266323821 01:16:00 01:02 Palestrina Hosanna Canadian Brass 05433 RCA 63238 090266323821 01:18:1741:41 Schubert Piano Sonata in A, D. 959 Mitsuko Uchida 05116 Philips 289 456 028945657929 579 02:01:2804:15 Grieg The Last Spring from Two Capella 11036 Naxos 8.578009 747313800971 Elegiac Melodies, Op. 34 Istropolitana/Leaper 02:06:4343:50 Balakirev Symphony No. 1 in C City of Birmingham 00845 EMI 47505 077774750523 Symphony/Jarvi 02:51:4808:17 Beethoven Overture to Egmont, Op. 84 Berlin 00470 DG 415 506 028941550620 Philharmonic/Karajan 03:01:3511:14 Liszt Mephisto Waltz No. 1 Murray Perahia 02233 Sony 47180 07464471802 03:13:4903:44 Tippett Dance, Clarion Air (madrigal for Choir of Christ Church 00783 Nimbus 5266 D 110593 five voices) Cathedral, Oxford/Darlington 03:18:4840:41 Alfven Symphony No. 1 In F minor, Stockholm 01531 BIS 395 731859000395 Op. 7 Philharmonic/Jarvi 4 04:00:5932:43 Taneyev, A. -

The Classical Station, WCPE 1 Start Runs Composer Title Performerslib # Label Cat

Tue, Jan 26, 2021 - The Classical Station, WCPE 1 Start Runs Composer Title PerformersLIb # Label Cat. # Barcode 00:01:30 10:39 Mozart Adagio in B minor, K. 540 Mitsuko Uchida 00264 Philips 412 616 028941261625 00:13:3945:17 Dvorak Cello Concerto in B minor, Op. du Pre/Swedish Radio 07040 Teldec 85340 685738534029 104 Symphony/Celibidache 01:00:2631:11 Beethoven String Quartet No. 9 in C, Op. Tokyo String Quartet 04508 Harmonia 807424 093046742362 59 No. 3 Mundi 01:32:3708:09 Mozart Adagio & Fugue in C minor for Berlin 06660 DG 0005830 028947759546 Strings K. 546 Philharmonic/Karajan 01:42:1618:09 Telemann Paris Quartet No. 11 Kuijken 04867 Sony 63115 074646311523 Bros/Leonhardt 02:01:5529:22 Mozart Sinfonia Concertante in E flat, Frang/Rysanov/Arcang 12341 Warner 08256462 825646276776 K. 364 elo/Cohen Classics 76776 02:32:1726:39 Brahms Clarinet Trio in A minor, Op. Stoltzman/Ax/Ma 02937 Sony 57499 074645749921 114 Classical 03:00:2611:52 Liszt Mephisto Waltz No. 1 Evgeny Kissin 06623 RCA 58420 828765842020 03:13:1834:42 Strauss, R. Symphony in D minor Hong Kong 03667 Marco Polo 8.220323 73009923232 Philharmonic/Scherme rhorn 03:49:0009:52 Schubert Overture to Rosamunde, D. Leipzig Gewandhaus 00217 Philips 412 432 028941243225 797 Orchestra/Masur 04:00:2215:04 Haydn Piano Sonata No. 50 in D Julia Cload 02053 Meridian 84083 N/A 04:16:2628:32 Mozart Symphony No. 29 in A, K. 201 Prague Chamber 05596 Telarc 80300 089408030024 Orch/Mackerras 04:45:58 12:20 Webern In the Summer Wind Philadelphia 10424 Sony 88725417 887254172024 Orchestra/Ormandy 202 04:59:4806:23 Lehar Merry Widow Waltz Richard Hayman 08261 Naxos 8.578041- 747313804177 Symphony 42 05:07:11 21:52 Rachmaninoff Rhapsody on a Theme of Entremont/Philadelphia 04207 Sony 46541 07464465412 Paganini, Op. -

Franz Schubert's Impromptus D. 899 and D. 935: An

FRANZ SCHUBERT’S IMPROMPTUS D. 899 AND D. 935: AN HISTORICAL AND STYLISTIC STUDY A doctoral document submitted to the Division of Research and Advanced Studies of the University of Cincinnati In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS In the Keyboard Studies Division of the College-Conservatory of Music 2005 by Ina Ham M.M., Cleveland Institute of Music, 1999 M.M., Seoul National University, 1996 B.M., Seoul National University, 1994 Committee Chair: Dr. Melinda Boyd ABSTRACT The impromptu is one of the new genres that was conceived in the early nineteenth century. Schubert’s two sets of impromptus D. 899 and D. 935 are among the most important examples to define this new genre and to represent the composer’s piano writing style. Although his two sets of four impromptus have been favored in concerts by both the pianists and the audience, there has been a lack of comprehensive study of them as continuous sets. Since the tonal interdependence between the impromptus of each set suggests their cyclic aspects, Schubert’s impromptus need to be considered and be performed as continuous sets. The purpose of this document is to provide useful resources and performance guidelines to Schubert’s two sets of impromptus D. 899 and D. 935 by examining their historical and stylistic features. The document is organized into three chapters. The first chapter traces a brief history of the impromptu as a genre of piano music, including the impromptus by Jan Hugo Voŕišek as the first pieces in this genre. -

An Investigation of the Sonata-Form Movements for Piano by Joaquín Turina (1882-1949)

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by University of Birmingham Research Archive, E-theses Repository CONTEXT AND ANALYSIS: AN INVESTIGATION OF THE SONATA-FORM MOVEMENTS FOR PIANO BY JOAQUÍN TURINA (1882-1949) by MARTIN SCOTT SANDERS-HEWETT A dissertatioN submitted to The UNiversity of BirmiNgham for the degree of MASTER OF MUSIC DepartmeNt of Music College of Arts aNd Law The UNiversity of BirmiNgham September 2014 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. ABSTRACT Composed between 1909 and 1946, Joaquín Turina’s five piano sonatas, Sonata romántica, Op. 3, Sanlúcar de Barrameda, Op. 24, Sonata Fantasía, Op. 59, Concierto sin Orquesta, Op. 88 and Rincón mágico, Op. 97, combiNe established formal structures with folk-iNspired themes and elemeNts of FreNch ImpressioNism; each work incorporates a sonata-form movemeNt. TuriNa’s compositioNal techNique was iNspired by his traiNiNg iN Paris uNder ViNceNt d’Indy. The unifying effect of cyclic form, advocated by d’Indy, permeates his piano soNatas, but, combiNed with a typically NoN-developmeNtal approach to musical syNtax, also produces a mosaic-like effect iN the musical flow. -

Performances As Analyses of Cyclic Macroform in Arnold Schoenberg's

Shaping Form: Performances as Analyses of Cyclic Macroform in Arnold Schoenberg’s Sechs kleine Klavierstücke, op. 19 (1911), in the Recordings of Eduard Steuermann and Other Pianists * Christian U and Thomas Glaser NOTE: The examples for the (text-only) PDF version of this item are available online at: hps://www.mtosmt.org/issues/mto.20.26.4/mto.20.26.4.u.php KEYWORDS: analysis and performance, Arnold Schoenberg, corpus study of musical recordings, Eduard Steuermann, history of musical performance, Sechs kleine Klavierstücke, Six Lile Piano Pieces, op. 19 ABSTRACT: Arnold Schoenberg’s Sechs kleine Klavierstücke (Six Lile Piano Pieces), op. 19 (1911), offer a fruitful case study to examine and categorize performers’ strategies in regard to their form- shaping characteristics. A thorough quantitative and qualitative analysis of 46 recordings from 41 pianists (recorded between 1925 to 2018), including six recordings from Eduard Steuermann, the leading pianist of the Second Viennese School, scrutinizes the interdependency between macro- and microformal pianistic approaches to this cycle. In thus tracing varying conceptions of a performance-shaped cyclic form and their historical contexts, the continuous unfurling of the potential of Schoenberg’s musical ideas in both “structuralist” and “rhetorical” performance styles is systematically explored, offering a fresh approach to the controversial discussion on how analysis and performance might relate to one another. DOI: 10.30535/mto.26.4.9 Received January 2020 Volume 26, Number 4, December 2020 Copyright © 2020 Society for Music Theory 1. The Mutual Productivity of Performance and Analysis [1.1] In his 2016 book Performative Analysis, Jeffrey Swinkin, makes the striking observation that it can hardly be the point of a musical performance to project or communicate analytical understanding. -

A Discussion of the Piano Sonata No. 2 in D Minor, Op

A DISCUSSION OF THE PIANO SONATA NO. 2 IN D MINOR, OP. 14, BY SERGEI PROKOFIEV A PAPER ACCOMPANYING A THREE CREDIT-HOUR CREATIVE PROJECT RECITAL SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE MASTER OF MUSIC BY QINYUAN LIN DR. ROBERT PALMER‐ ADVISOR BALL STATE UNIVERSITY MUNCIE, INDIANA JULY 2010 Preface The goal of this paper is to introduce the piece, provide historical background, and focus on the musical analysis of the sonata. The introduction of the piece will include a brief biography of Sergei Prokofiev and the circumstance in which the piece was composed. A general overview of the composition, performance, and perception of this piece will be discussed. The bulk of the paper will focus on the musical analysis of Piano Sonata No. 2 from my perspective as a performer of the piece. It will be broken into four sections, one each for the four movements in the sonata. In the discussion for each movement, I will analyze the forms used as well as required techniques and difficulties to be considered by the pianist. The conclusion will summarize the discussion. i Table of Contents Preface ________________________________________________________________ i Introduction ____________________________________________________________ 1 The First Movement: Allegro, ma non troppo __________________________________ 5 The Second Movement: Scherzo ____________________________________________ 9 The Third Movement: Andante ____________________________________________ 11 The Fourth Movement: Vivace ____________________________________________ 13 Conclusion ____________________________________________________________ 17 Bibliography __________________________________________________________ 18 ii Introduction Sergei Prokofiev was born in 1891 to parents Sergey and Mariya and grew up in comfortable circumstances. His mother, Mariya, had a feeling for the arts and gave the young Prokofiev his first piano lessons at the age of four. -

Andras Schiff Franz Schubert Sonatas & Impromptus

Andras Schiff Franz Schubert Sonatas & Impromptus -• ECM NEW SERIES Franz Schubert Vier Impromptus D 899 Sonate in c-Moll D 958 Drei Klavierstücke D 946 Sonate in A-Dur D 959 Andräs Schiff Fortepiano Franz Schubert (1797-1828) II 1-4 Vier Impromptus D899 1-3 Drei Klavierstücke D 946 Allegro molto moderato in c-Moll 9:32 Allegro assai in es-Moll 9:12 Allegro in Es-Dur 4:39 Allegretto in Es-Dur 11 :46 Andante in Ges-Dur 4:59 Allegro in C-Dur 5:31 Allegretto in As-Dur 7: 21 4-7 Sonate in A-Dur D959 5-8 Sonate in c-Moll D958 Allegro 15:45 Allegro 10:35 Andantino 7:13 Adagio 7:00 Scherzo. Allegro vivace - Trio 5:30 Menuett. Allegretto - Trio 3:04 Rondo. Allegretto 12:35 Allegro 9:13 Beethoven's sphere "Secretly, I hope to be able to make something of myself, but who can do any thing after Beethoven?" Schubert's remark, allegedly made to his childhood friendJosef von Spaun, gives us an indication of how strongly he feit himself to be in the shadow of the great composer he was too inhibited ever to approach. For his part, Beethoven cannot have been unaware of Schubert's presence in Vienna. The younger composer's first piano sonata to appear in print - the Sonata in A minor D 845 - bore a dedication to Beethoven's most generous and ardent pa tron, Archduke Rudolph of Austria. Moreover, the work was favourably reviewed in the Leipzig Al/gemeine musikalische Zeitung - a journal which Beethoven is known to have read. -

Function and Structure of Transitions in Sonata — Form Music of Mozart Robert Batt

Document généré le 1 oct. 2021 08:37 Canadian University Music Review Revue de musique des universités canadiennes --> Voir l’erratum concernant cet article Function and Structure of Transitions in Sonata — Form Music of Mozart Robert Batt Volume 9, numéro 1, 1988 URI : https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/1014927ar DOI : https://doi.org/10.7202/1014927ar Aller au sommaire du numéro Éditeur(s) Canadian University Music Society / Société de musique des universités canadiennes ISSN 0710-0353 (imprimé) 2291-2436 (numérique) Découvrir la revue Citer cet article Batt, R. (1988). Function and Structure of Transitions in Sonata — Form Music of Mozart. Canadian University Music Review / Revue de musique des universités canadiennes, 9(1), 157–201. https://doi.org/10.7202/1014927ar All Rights Reserved © Canadian University Music Society / Société de musique Ce document est protégé par la loi sur le droit d’auteur. L’utilisation des des universités canadiennes, 1988 services d’Érudit (y compris la reproduction) est assujettie à sa politique d’utilisation que vous pouvez consulter en ligne. https://apropos.erudit.org/fr/usagers/politique-dutilisation/ Cet article est diffusé et préservé par Érudit. Érudit est un consortium interuniversitaire sans but lucratif composé de l’Université de Montréal, l’Université Laval et l’Université du Québec à Montréal. Il a pour mission la promotion et la valorisation de la recherche. https://www.erudit.org/fr/ FUNCTION AND STRUCTURE OF TRANSITIONS IN SONATA-FORM MUSIC OF MOZART Robert Batt The transition, sometimes referred to as the bridge, is usually regarded as the section of sonata form responsible for modulating from the pri• mary to the secondary key as well as for effecting a structural contrast between the two thematic sections.