General Councils of the Fifteenth Century Joseph Vietri a Thesis In

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

This Electronic Thesis Or Dissertation Has Been Downloaded from Explore Bristol Research

This electronic thesis or dissertation has been downloaded from Explore Bristol Research, http://research-information.bristol.ac.uk Author: Jenkins, Clare Helen Elizabeth Title: Jansenism as literature : a study into the influence of Augustinian theology on seventeenth-century French literature General rights Access to the thesis is subject to the Creative Commons Attribution - NonCommercial-No Derivatives 4.0 International Public License. A copy of this may be found at https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/legalcode This license sets out your rights and the restrictions that apply to your access to the thesis so it is important you read this before proceeding. Take down policy Some pages of this thesis may have been removed for copyright restrictions prior to having it been deposited in Explore Bristol Research. However, if you have discovered material within the thesis that you consider to be unlawful e.g. breaches of copyright (either yours or that of a third party) or any other law, including but not limited to those relating to patent, trademark, confidentiality, data protection, obscenity, defamation, libel, then please contact [email protected] and include the following information in your message: •Your contact details •Bibliographic details for the item, including a URL •An outline nature of the complaint Your claim will be investigated and, where appropriate, the item in question will be removed from public view as soon as possible. Jansenism as Literature: A Study into the Influence of Augustinian Theology on Seventeenth-Century French Literature Clare Helen Elizabeth Jenkins A Dissertation submitted to the University of Bristol in accordance with the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Faculty of Arts. -

Tables of Contemporary Chronology, from the Creation to A. D. 1825

: TABLES OP CONTEMPORARY CHUONOLOGY. FROM THE CREATION, TO A. D. 1825. \> IN SEVEN PARTS. "Remember the days of old—consider the years of many generations." 3lorttatttt PUBLISHED BY SHIRLEY & HYDE. 1629. : : DISTRICT OF MAItfE, TO WIT DISTRICT CLERKS OFFICE. BE IT REMEMBERED, That on the first day of June, A. D. 1829, and in the fifty-third year of the Independence of the United States of America, Messrs. Shiraey tt Hyde, of said District, have deposited in this office, the title of a book, the right whereof they claim as proprietors, in the words following, to wit Tables of Contemporary Chronology, from the Creation, to A.D. 1825. In seven parts. "Remember the days of old—consider the years of many generations." In conformity to the act of the Congress of the United States, entitled " An Act for the encouragement of learning, by securing the copies of maps, charts, and books, to the authors and proprietors of such copies, during the times therein mentioned ;" and also to an act, entitled "An Act supplementary to an act, entitled An Act for the encouragement of learning, by securing the copies of maps, charts and books, to the authors and proprietors of such copies, during the times therein mentioned ; and for extending the benefits thereof to the arts of designing, engraving, and etching historical and other prints." J. MUSSEV, Clerk of the District of Maine. A true copy as of record, Attest. J MUSSEY. Clerk D. C. of Maine — TO THE PUBLIC. The compiler of these Tables has long considered a work of this sort a desideratum. -

Catholic Clergy There Are Many Roles Within the Catholic Church for Both Ordained and Non-Ordained People

Catholic Clergy There are many roles within the Catholic Church for both ordained and non-ordained people. A non-ordained person is typically referred to as a lay person, or one who is not a member of the clergy. One who is ordained is someone who has received the sacrament of Holy Orders. In the Catholic Church only men may be ordained to the Clergy, which sets us apart from other Christian denominations. The reasoning behind this is fairly straightforward; Since God himself, in His human form of Jesus Christ, instituted the priesthood by the formation of the 12 Apostles which were all male, The Church is bound to follow His example. Once a man is ordained, he is not allowed to marry, he is asked to live a life of celibacy. However married men may become ordained Deacons, but if their wife passes away they do not remarry. It’s very rare, but there are instances of married men being ordained as priests within the Catholic Church. Most are converts from other Christian denominations where they served in Clerical roles, look up the story of Father Joshua Whitfield of Dallas Texas. At the top of the Catholic Clergy hierarchy is the Pope, also known as the Vicar of Christ, and the Bishop Rome. St. Peter was our very first Pope, Jesus laid his hands upon Peter and proclaimed “upon this rock I will build my church, and the gates of the netherworld shall not prevail against it.” ~MT 16:18. Our current Pope is Pope Francis, formally Cardinal Jorge Mario Bergoglio of Argentina. -

Establishing the Tudor Dynasty: the Role of Francesco Piccolomini in Rome As First Cardinal Protector of England

2017 IV Establishing the Tudor Dynasty: The Role of Francesco Piccolomini in Rome as First Cardinal Protector of England Susan May Article: Establishing the Tudor Dynasty: The Role of Francesco Piccolomini in Rome as First Cardinal Protector of England Establishing the Tudor Dynasty: The Role of Francesco Piccolomini in Rome as First Cardinal Protector of England1 Susan May Abstract: Between 1492 and 1503, Francesco Todeschini Piccolomini (1439–1503) was the first officially appointed Cardinal Protector of England. This paper focuses on a select few of his activities executed in that capacity for Henry Tudor, King Henry VII. Drawing particularly on two unpublished letters, it underscores the importance for King Henry of having his most trusted supporters translated to significant bishoprics throughout the land, particularly in the northern counties, and explores Queen Elizabeth of York’s patronage of the hospital and church of St Katharine-by-the-Tower in London. It further considers the mechanisms through which artists and humanists could be introduced to the Tudor court, namely via the communication and diplomatic infrastructure of Italian merchant-bankers. This study speculates whether, by the end of his long incumbency of forty-three years at the Sacred College, uncomfortably mindful of the extent of a cardinal’s actual and potential influence in temporal affairs, Piccolomini finally became reluctant to wield the power of the purple. Keywords: Francesco Todeschini Piccolomini; Henry VII; early Tudor; cardinal protector; St Katharine’s; Italian merchant-bankers ope for only twenty-six days following his election, taking the name of Pius III (Fig. 1), Francesco Todeschini Piccolomini (1439–1503) has understandably been P overshadowed in reputation by his high-profile uncle, Aeneas Silvius Piccolomini, Pope Pius II (1458–64). -

G:\ADULT Quizaug 2, 2020.P65

‘TEST YOUR FAITH ’ QUIZ FOR ADULTS August 2, 2020 “ O F P O P E S A ND C A R D I N A L S” Msgr. Pat Stilla (Scroll down to pages 2 & 3 for the correct answers ) T F 1. “The Vatican ” is an Italian City under the jurisdiction of the City of Rome. T F 2. St. Peter is buried under the central Papal altar in St. Peter’s Basilica. T F 3. “Roman Pontiff”, which is one of the Pope’s titles literally means, “Roman Bridge Builder”. T F 4. The Pope, who is sometimes called, the “Vicar of Christ”, is always dressed in white, because Christ wore a white robe when He walked the earth. T F 5. When one is elected Pope, his new name is chosen by the Cardinals. T F 6. After St. Peter, the name, “Peter” has never been chosen as a Pope’s name. T F 7. The name most frequently chosen by a Pope after his election, has been “Benedict”, used 16 times. T F 8. Since the Pope is not only the “Holy Father” of the entire world but also the Bishop of Rome, it is his obligation to care for the Parishioners, Bishops, Diocesan Priests and Parish Churches of the Diocese of Rome. T F 9. The Pope’s Cathedral as Bishop of Rome is St. Peter’s Basilica. T F 10. One little known title of the Pope is, “Servant of the servants of God”. T F 11. “Cardinal“ comes from a Greek word which means, a “Prince of the Church”. -

From Papal Bull to Racial Rule: Indians of the Americas, Race, and the Foundations of International Law

Vera: From Papal Bull to Racial Rule: Indians of the Americas, Race, an FROM PAPAL BULL TO RACIAL RULE: INDIANS OF THE AMERICAS, RACE, AND THE FOUNDATIONS OF INTERNATIONAL LAW KIM BENITA VERA* The "discovery" and conquest of the "New World" marked the inauguration of international law,' and constituted a watershed moment in the emergence of race in European thought.2 What might the coterminous rise of formative. moments in race thinking and international law suggest? In my provisional reflections on this question that follow, I trace juridical and religio-racial conceptions of indigenous peoples of the Americas as a central thread in the evolution of international law. I will begin with a discussion of the fifteenth-century papal bulls issued in regard to the Portugal-Spain disputes over lands in Africa and the Americas. I will then proceed to follow some strands of racial and juridical thought in the accounts of Francisco de Vitoria and Hugo Grotius, two founding figures in international law. I suggest that Vitoria's treatise, On the Indians Lately Discovered,3 evinces the beginnings of the shift Carl Schmitt identifies from the papal authority of the respublica Christiana to modern international law.4 Vitoria's account, moreover, is both proto-secular and proto-racial. * Assistant Professor, Legal Studies Department, University of Illinois at Springfield, J.D./Ph.D., Arizona State University, 2006. 1. See, e.g., CARL ScHMrT, THE NOMOS OF THE EARTH IN THE INTERNATIONAL LAW OF THE Jus PUBLICUM EUROPAEUM 49 (G. L. Ulmen trans., 2003). 2. DAVID THEO GOLDBERG, RACIST CULTURE: PHILOSOPHY AND THE POLITICS OF MEANING 62 (1993). -

Why Vatican II Happened the Way It Did, and Who’S to Blame

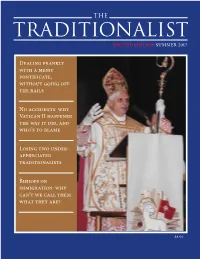

SPECIAL EDITION SUMMER 2017 Dealing frankly with a messy pontificate, without going off the rails No accidents: why Vatican II happened the way it did, and who’s to blame Losing two under- appreciated traditionalists Bishops on immigration: why can’t we call them what they are? $8.00 Publisher’s Note The nasty personal remarks about Cardinal Burke in a new EDITORIAL OFFICE: book by a key papal advisor, Cardinal Maradiaga, follow a pattern PO Box 1209 of other taunts and putdowns of a sitting cardinal by significant Ridgefield, Connecticut 06877 cardinals like Wuerl and even Ouellette, who know that under [email protected] Pope Francis, foot-kissing is the norm. And everybody half- Your tax-deductible donations for the continu- alert knows that Burke is headed for Church oblivion—which ation of this magazine in print may be sent to is precisely what Wuerl threatened a couple of years ago when Catholic Media Apostolate at this address. he opined that “disloyal” cardinals can lose their red hats. This magazine exists to spotlight problems like this in the PUBLISHER/EDITOR: Church using the print medium of communication. We also Roger A. McCaffrey hope to present solutions, or at least cogent analysis, based upon traditional Catholic teaching and practice. Hence the stress in ASSOCIATE EDITORS: these pages on: Priscilla Smith McCaffrey • New papal blurtations, Church interference in politics, Steven Terenzio and novel practices unheard-of in Church history Original logo for The Traditionalist created by • Traditional Catholic life and beliefs, independent of AdServices of Hollywood, Florida. who is challenging these Can you help us with a donation? The magazine’s cover price SPECIAL THANKS TO: rorate-caeli.blogspot.com and lifesitenews.com is $8. -

Ave Papa Ave Papabile the Sacchetti Family, Their Art Patronage and Political Aspirations

FROM THE CENTRE FOR REFORMATION AND RENAISSANCE STUDIES Ave Papa Ave Papabile The Sacchetti Family, Their Art Patronage and Political Aspirations LILIAN H. ZIRPOLO In 1624 Pope Urban VIII appointed Marcello Sacchetti as depositary general and secret treasurer of the Apostolic Cham- ber, and Marcello’s brother, Giulio, bishop of Gravina. Urban later gave Marcello the lease on the alum mines of Tolfa and raised Giulio to the cardinalate. To assert their new power, the Sacchetti began commissioning works of art. Marcello discov- ered and promoted leading Baroque masters, such as Pietro da Cortona and Nicolas Poussin, while Giulio purchased works from previous generations. In the eighteenth century, Pope Benedict XIV bought the collection and housed it in Rome’s Capitoline Museum, where it is now a substantial portion of the museum’s collection. By focusing on the relationship between the artists in ser- vice and the Sacchetti, this study expands our knowledge of the artists and the complexity of the processes of agency in the fulfillment of commissions. In so doing, it underlines how the Sacchetti used art to proclaim a certain public image and to announce Cardinal Giulio’s candidacy to the papal throne. ______ copy(ies) Ave Papa Ave Papabile Payable by cheque (to Victoria University - CRRS) ISBN 978-0-7727-2028-2 or by Visa/Mastercard $24.50 Name as on card ___________________________________ (Outside Canada, please pay in US $.) Visa/Mastercard # _________________________________ Price includes applicable taxes. Expiry date _____________ Security code ______________ Send form with cheque/credit card Signature ________________________________________ information to: Publications, c/o CRRS Name ___________________________________________ 71 Queen’s Park Crescent East Address __________________________________________ Toronto, ON M5S 1K7 Canada __________________________________________ The Centre for Reformation and Renaissance Studies Victoria College in the University of Toronto Tel: 416-585-4465 Fax: 416-585-4430 [email protected] www.crrs.ca . -

LES ENLUMINURES,LTD Les Enluminures

LES ENLUMINURES,LTD Les Enluminures 2970 North Lake Shore Drive 11B Le Louvre des Antiquaires Chicago, Illinois 60657 2 place du Palais-Royal 75001 Paris tel. 1-773-929-5986 fax. 1-773-528-3976 tél : 33 1 42 60 15 58 [email protected] fax : 33 1 40 15 00 25 [email protected] BONIFACE VIII (1294-1303), Liber Sextus, with the Glossa Ordinaria of Johannes Andreae and the Regulae Iuris In Latin, illuminated manuscript, on parchment [France, likely Avignon, c. 1350] 228 folios, parchment, complete (1-910, 10 8, 1112, 12 8, 13-1412, 15-1910, 2011, 199 is a folio detached, 21-2210, 234, 225 and 227 are detached folios), quires 21 to 23 bear an old foliation that goes from 1 to 22 and are distinctive both by their mise-en-page and their texts, horizontal catchwords for quires 1-9 and 21-22, vertical for quires 10-20, ruling in pen: for the Liber Sextus 2 columns of variable length with surrounding glosses (57-60 lines of gloss; justification 295/325 x 195/200 mm); in quires 21-23, 2 columns (52-54 lines, justification 310 x 185), written in littera bononiensis by several hands, smaller and more compressed for the gloss, of middle size, more regular and larger for the Regulae iuris, decoration of numerous initals in red and blue, that of quires 1 and 5 is a little more finished, the initials there are delicately calligraphed with penwork in red with violet and blue with red, large 4 ILLUMINATED INITIALS on ff. 2r and 4r, a little deteriorated in blue, pale green, pink, orange, and gold and silver on black ground with white foliage, containing rinceaux and animals, the first surmounted by a rabbit; at the beginning of the text a large initial with penwork and foliage, ending in a floral frame separating the text from the gloss, with an erased shield in the lower margin. -

The Christian Doctrine of Discovery

The Christian Doctrine of Discovery By Dan Whittemore, Denver, Colorado, USA For centuries, indigenous peoples around the world have suffered the disastrous impact of European colonization. As a Christian, descended from Europeans, I am remorseful and repentant because I am complicit in this problem. Undoubtedly some of my ancestors helped create the situation that has resulted in discrimination and prejudicial and derogatory concepts of the original inhabitants. Broken contracts, ignorance of native culture and spirituality, and illegitimate appropriation of lands have contributed to poverty and psychological damage that persist. We are challenged to examine the root causes and make corrections. The centuries-old Christian Doctrine of Discovery, if repudiated, could initiate justice for all indigenous people. The Doctrine of Discovery is the premise that European Christian explorers who “discovered” other lands had the authority to claim those lands and subdue, even enslave, peoples simply because they were not Christian. This concept has become embedded in the legal policies of countries throughout the world. This is an issue of greed, oppression, colonialism, and racism. The doctrine’s origins can be traced to Pope Nicholas V, who issued the papal bull1 Romanus Pontifex in 1455 CE. The bull allowed Portugal to claim and conquer lands in West Africa. After Christopher Columbus began conquering newly “found” lands in the Americas, Pope Alexander VI granted to Spain the right to claim these lands with the papal bull, Inter caetera, issued in 1493. The Treaty of Tordesillas settled competition between Spain and Portugal. It established two principles: 1) that only non-Christian lands could be taken, and 2) that potential discoveries would be allocated between Portugal and Spain by drawing a line of demarcation. -

The Magisterium of the Faculty of Theology of Paris in the Seventeenth Century

Theological Studies 53 (1992) THE MAGISTERIUM OF THE FACULTY OF THEOLOGY OF PARIS IN THE SEVENTEENTH CENTURY JACQUES M. GRES-GAYER Catholic University of America S THEOLOGIANS know well, the term "magisterium" denotes the ex A ercise of teaching authority in the Catholic Church.1 The transfer of this teaching authority from those who had acquired knowledge to those who received power2 was a long, gradual, and complicated pro cess, the history of which has only partially been written. Some sig nificant elements of this history have been overlooked, impairing a full appreciation of one of the most significant semantic shifts in Catholic ecclesiology. One might well ascribe this mutation to the impetus of the Triden tine renewal and the "second Roman centralization" it fostered.3 It would be simplistic, however, to assume that this desire by the hier archy to control better the exposition of doctrine4 was never chal lenged. There were serious resistances that reveal the complexity of the issue, as the case of the Faculty of Theology of Paris during the seventeenth century abundantly shows. 1 F. A. Sullivan, Magisterium (New York: Paulist, 1983) 181-83. 2 Y. Congar, 'Tour une histoire sémantique du terme Magisterium/ Revue des Sci ences philosophiques et théologiques 60 (1976) 85-98; "Bref historique des formes du 'Magistère' et de ses relations avec les docteurs," RSPhTh 60 (1976) 99-112 (also in Droit ancien et structures ecclésiales [London: Variorum Reprints, 1982]; English trans, in Readings in Moral Theology 3: The Magisterium and Morality [New York: Paulist, 1982] 314-31). In Magisterium and Theologians: Historical Perspectives (Chicago Stud ies 17 [1978]), see the remarks of Y. -

The Restoration of the Roman Catholic Hierarchy in England 1850: a Catholic Position

University of Windsor Scholarship at UWindsor Electronic Theses and Dissertations Theses, Dissertations, and Major Papers 1-1-1958 The restoration of the Roman Catholic hierarchy in England 1850: A Catholic position. Eddi Chittaro University of Windsor Follow this and additional works at: https://scholar.uwindsor.ca/etd Recommended Citation Chittaro, Eddi, "The restoration of the Roman Catholic hierarchy in England 1850: A Catholic position." (1958). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 6283. https://scholar.uwindsor.ca/etd/6283 This online database contains the full-text of PhD dissertations and Masters’ theses of University of Windsor students from 1954 forward. These documents are made available for personal study and research purposes only, in accordance with the Canadian Copyright Act and the Creative Commons license—CC BY-NC-ND (Attribution, Non-Commercial, No Derivative Works). Under this license, works must always be attributed to the copyright holder (original author), cannot be used for any commercial purposes, and may not be altered. Any other use would require the permission of the copyright holder. Students may inquire about withdrawing their dissertation and/or thesis from this database. For additional inquiries, please contact the repository administrator via email ([email protected]) or by telephone at 519-253-3000ext. 3208. THE RESTORATION OF THE ROMAN CATHOLIC HIERARCHY IN ENGLAND ^ 1850 1 A CATHOLIC POSITION Submitted to the Department of History of Assumption University of Windsor in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts. by Eddi Chittaro, B.A* Faculty of Graduate Studies 1 9 5 8 Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner.