51916 1961 LIW.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Office of the Sr. Deputy. Accountant General (A&E), Manipur, Imphal

Departmental Classified Abstract (Payment) Report ID : WM0REP032 Run Date : 15/06/2021 for Page 1 of 2 The Office of the Sr. Deputy. Accountant General (A&E), Manipur, Imphal Month of Account 04/2020: Department Name 63 Public Health Engineering Department Major Sub Minor Sub Detail Object Scheme Source Parameter Head Major Head Head Head Head Description Description Description Amount Head 4215 01 101 0005 000 27 VALLEY W/S. Maintenance Division- VOTED VALLEY 60,821.00 Imphal NULL Minor II, PHED Water Works Supply 60,821.00 Object Head Total : Detail Head Total : 60,821.00 Sub Head Total : 60,821.00 Minor Head Total : 60,821.00 Sub Major Head Total : 60,821.00 Major Head Total : 60,821.00 8782 00 102 0001 000 00 HILL Ukhrul Division, PHED NULL 22,500.00 (i) NULL NULL Remittan ces into Object Head Total : 22,500.00 Treasuri 00 VALLEY Bishnupur Division, PHED NULL 28,500.00 es/Banks NULL Object Head Total : 28,500.00 00 VALLEY Imphal West Division, PHED NULL 2,87,637.00 NULL Object Head Total : 2,87,637.00 00 VALLEY Imphal East Division, PHED NULL 3,97,754.00 NULL Object Head Total : 3,97,754.00 00 VALLEY W/S. Maintenance Division- NULL 4,38,400.00 NULL I, PHED Departmental Classified Abstract (Payment) Report ID : WM0REP032 Run Date : 15/06/2021 for Page 2 of 2 The Office of the Sr. Deputy. Accountant General (A&E), Manipur, Imphal Month of Account 04/2020: Department Name 63 Public Health Engineering Department Major Sub Minor Sub Detail Object Scheme Source Parameter Head Major Head Head Head Head Description Description Description Amount Head 8782 00 102 0001 000 00 Object Head Total : 4,38,400.00 NULL Detail Head Total : 11,74,791.00 Sub Head Total : 11,74,791.00 Minor Head Total : 11,74,791.00 Sub Major Head Total : 11,74,791.00 Major Head Total : 11,74,791.00 Total for Public Health Engineering Department : 12,35,612.00 Departmental Classified Abstract (Payment) Report ID : WM0REP032 Run Date : 15/06/2021 for Page 1 of 10 The Office of the Sr. -

1 District Census Handbook-Churachandpur

DISTRICT CENSUS HANDBOOK-CHURACHANDPUR 1 DISTRICT CENSUS HANDBOOK-CHURACHANDPUR 2 DISTRICT CENSUSHANDBOOK-CHURACHANDPUR T A M T E MANIPUR S N A G T E L C CHURACHANDPUR DISTRICT I O L N R G 5 0 5 10 C T SENAPATI A T D I S T R I DISTRICT S H I B P Kilpmetres D To Ningthoukhong M I I From From Jiribam Nungba S M iver H g R n Ira N A r e U iv k R ta P HENGLEP ma Lei S Churachandpur District has 10 C.D./ T.D. Blocks. Tipaimukh R U Sub - Division has 2 T.D. Blocks as Tipaimukh and Vangai Range. Thanlon T.D. Block is co-terminus with the Thanlon r R e Sub-Diovision. Henglep T.D. Block is co-terminus with the v S i r e R v Churachandpur North Sub-Division. Churachandpur Sub- i i R C H U R A C H A N D P U R N O R T H To Imphal u l Division has 5 T.D. Blocks as Lamka,Tuibong, Saikot, L u D L g Sangaikot and Samulamlan. Singngat T.D. Block is co- l S U B - D I V I S I O N I S n p T i A a terminus with the Singngat Sub-Division. j u i R T u INDIAT NH 2 r I e v i SH CHURACHANDPUR C R k TUIBONG ra T a RENGKAI (C T) 6! ! BIJANG ! B G ! P HILL TOWN (C T) ! ZENHANG LAMKA (C T) 6 G! 6 3 M T H A N L O N CCPUR H.Q. -

MANIPUR a Joint Initiative of Government of India and Government of Manipur

24 X 7 POWER FOR ALL - MANIPUR A Joint Initiative of Government of India and Government of Manipur Piyush Goyal Minister of State (Independent Charge) for Government of India Power, Coal, New & Renewable Energy Foreword Electricity consumption is one of the most important indicator that decides the development level of a nation. The Government of India is committed to improving the quality of life of its citizens through higher electricity consumption. Our aim is to provide each household access to electricity, round the clock. The ‘Power for All’ programme is a major step in this direction. This joint initiative of Government of India and Government of Manipur aims to further enhance the satisfaction levels of the consumers and improve the quality of life of people through 24x7- power supply. This would lead to rapid economic development of the state in primary, secondary & tertiary sectors resulting in inclusive development. I compliment the Government of Manipur and wish them all the best for implementation of this programme. The Government of India will complement the efforts of Government of Manipur in bringing uninterrupted quality power to each household, industry, commercial business, small & medium enterprise and establishment, any other public needs and adequate power to agriculture consumer as per the state policy. Government of Okram Ibobi Singh Manipur Chief Minister of Manipur Foreword Electricity is critical to livelihoods and essential to well-being. Dependable electricity is the lifeline of industrial and commercial businesses, as well as a necessity for the productivity and comfort of residential customers. The implementation of 24x7 “Power For All” programme is therefore a welcome initiative. -

Districts of Manipur State

Manipur State Selected Economic Indicators. Sl. Items Ref. Year Unit Particulars No. 1. Geographical Area 2011 Census '000 Sq. Km. 22.327 2. Population 2011 Census Lakh No. 27.22 3. Density -do- Persons per 121 Sq. Km. 4. Sex Ratio -do- Females per 987 '000 Males 5. Percentage of Urban Population to -do- Percentage 43 the total population 6. Average Annual Exponential Growth 2001-2011 -do- 1.86% Rate 7. Population Below Poverty Line (As 1999-2000 -do- 28.54% per Planning Commission estimates) 8. Literacy rate : (i) Persons (ii) Male (iii) 2011 Census -do- i) 79.85% Female ii) 85.48% iii)77.15% 9. Gross State Domestic Product 2004-05 to 2010- (GSDP) at factor cost : 2011 (Q) Rs. in crore 9198.14 (i) At current prices -do- -do- 7184.09 (ii) At constant (1993-94) prices 10. Net State Domestic Product (NSDP) at factor cost -do- -do- 8228.31 (i) At current prices -do- -do- 6548.20 (ii) At constant (1993-94) prices 11. Per Capita NSDP (i) At current prices 2003-2004 Rupees 29684 (ii) At constant (1993-94) prices -do- 23298 12. Index of Agricultural Production 2002-2003 (P) - 3325 (Base: Triennium ending 1981- 82=100) 13. Total cropped area 1999-2000 Lakh hectare 1,65,787 14. Net area sown -do- -do- 1,55,232 15. Index of IIBtrial Production (Base : 2002-2003 (P) - 502 1993-94=100 16. Post office per lakh population 2017 (December) No. 25.75 17. All scheduled commercial banks per 2017 (December) Nos. 6.87 lakh population 18. -

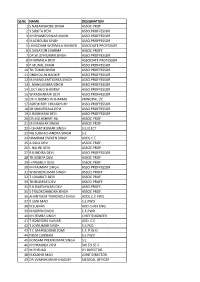

Slno Name Designation 1 S.Nabakishore Singh Assoc.Prof 2 Y.Sobita Devi Asso.Proffessor 3 Kh.Bhumeshwar Singh

SLNO NAME DESIGNATION 1 S.NABAKISHORE SINGH ASSOC.PROF 2 Y.SOBITA DEVI ASSO.PROFFESSOR 3 KH.BHUMESHWAR SINGH. ASSO.PROFFESSOR 4 N.ACHOUBA SINGH ASSO.PROFFESSOR 5 LUNGCHIM WORMILA HUNGYO ASSOCIATE PROFESSOR 6 K.SANATON SHARMA ASSOC.PROFF 7 DR.W.JOYKUMAR SINGH ASSO.PROFFESSOR 8 N.NIRMALA DEVI ASSOCIATE PROFESSOR 9 P.MUNAL SINGH ASSO.PROFFESSOR 10 TH.TOMBI SINGH ASSO.PROFFESSOR 11 ONKHOLUN HAOKIP ASSO.PROFFESSOR 12 M.MANGLEMTOMBA SINGH ASSO.PROFFESSOR 13 L.MANGLEMBA SINGH ASSO.PROFFESSOR 14 LUCY JAJO SHIMRAY ASSO.PROFFESSOR 15 W.RADHARANI DEVI ASSO.PROFFESSOR 16 DR.H.IBOMCHA SHARMA PRINCIPAL I/C 17 ASHOK ROY CHOUDHURY ASSO.PROFFESSOR 18 SH.SHANTIBALA DEVI ASSO.PROFFESSOR 19 K.RASHMANI DEVI ASSO.PROFFESSOR 20 DR.MD.ASHRAF ALI ASSOC.PROF 21 M.MANIHAR SINGH ASSOC.PROF. 22 H.SHANTIKUMAR SINGH S.E,ELECT. 23 NG SUBHACHANDRA SINGH S.E. 24 NAMBAM DWIJEN SINGH ADDL.C.E. 25 A.SILLA DEVI ASSOC.PROF. 26 L.NALINI DEVI ASSOC.PROF. 27 R.K.INDIRA DEVI ASSO.PROFFESSOR 28 TH.SOBITA DEVI ASSOC.PROF. 29 H.PREMILA DEVI ASSOC.PROF. 30 KH.RAJMANI SINGH ASSO.PROFFESSOR 31 W.BINODKUMAR SINGH ASSCO.PROFF 32 T.LOKABATI DEVI ASSOC.PROF. 33 TH.BINAPATI DEVI ASSCO.PROFF. 34 R.K.RAJESHWARI DEVI ASSO.PROFF., 35 S.TRILOKCHANDRA SINGH ASSOC.PROF. 36 AHANTHEM TOMCHOU SINGH ADDL.C.E.PWD 37 K.SANI MAO S.E.PWD 38 N.SUBHAS ADD.CHIEF ENG. 39 N.NOREN SINGH C.E,PWD 40 KH.TEMBA SINGH CHIEF ENGINEER 41 T.ROBINDRA KUMAR ADD. C.E. -

Village Survey Monograph, 8 Ningel, Part VI, Vol-XXII

CENSUS OF INDIA 1961 VOLUME XXII MANIPUR PART VI Village Survey Monographs 8. NINGEL R. K. BJRENDRA SINGH of the Manipur Civil Service Superintendent of Census Operations, Manipur FINAL LIST OF VILLAGES SELECTED FOR SOCIO-ECONOMIC SURVEY Name of Village Name of Sub-division 1. Ithing Bishenpur 2. Keisamthong Imphal West 3. Khousabung Ch urachandpur 4. Konpui Do. 5. Liwachangning Tengnoupal 6. Longa Koireng Mao & Sadar Hills 7. Minuthong . ImphaJ West 8. Ningel'" Thoubal 9. Oinam Sawombung Imphal West 10. Pherzawl Churachandpur 11. Phunan Sambum . Tengnoupal 12. Sekmai Imphal West 13. Thangjing Chiru Mao & Sadar Hills 14. Thingkangphai Churachandpur 15. Toupokpi Tengnoupal *Present Volume (No. 8 of the Series) ( iii) 1961 CENSUS PUBLICATIONS, MANIPUR (All the Census Publications of this Territory will bear Volume No. XXII) Part I-A General Report (Excluding Subsidiary Tables) Part I-B General Report (Subsidiary Tables) Part II I General Population Tables "I (with sub-parts )- Economic Tables )- j Cultural and Migration Tables j Part III Household Economic Tables l Part IV Housing Report and Tables ~ In one volume Part V Special Tables for Scheduled Castes and I Scheduled Tribes j Part VI vmage Survey Monographs Part VII-A Handicrafts Survey Reports Part VII-B Fairs and Festivals Part VIII-A Administration Report on Enumeration l Part VIII-B Administration Report on Tabulation .r Not for sale Part IX Census Atlas Volume STATE GOVERNMENT PUBLICATION 1. District Census Handbook CONTENTS PAGES FOREWORD vii PREFACE xi CHAPTERS T THE VILLAGE 1-8 IT PEOPLE AND THEIR MATERIAL EQUIPMENT 9-19 III ECONOMY 21-35 TV SOCIAL AND CULTURAL LIFE 37-55 V CONCLUSION 57 MAP AND SKETCHES 1. -

Churachandpur District

GOVERNMENT OF MANIPUR STATISTICAL YEAR BOOK CHURACHANDPUR DISTRICT 2014 DIRECTORATE OF ECONOMICS & STATISTICS GOVERNMENT OF MANIPUR LAMPHELPAT PREFACE The Statistical Year Book of Churachandpur District, 2014 is the 11th (Eleventh) issue of the publication earlier entitled, ‘Statistical Abstract of Churachandpur District, 2007’. In this issue, every effort has been made to update data to maximum extent possible and to improve the coverage and quality too. The source of data is indicated at the foot of each table. It is hoped that this publication will serve as useful guide to the Administrator, Planners and Data Users. This Publication has been prepared by the District Statistical Office, Churachandpur under the guidance of Shri. L. Heramani Singh, District Statistical Officer, Churachandpur with the assistance of Shri. Yangkholun Haokip, Inspector and staff of District Statistical Office, Churachandpur. The updation, comparability and consistency check of the data/information wherever possible, were carried out at the State Headquarters. However, in some cases where sub-division level data are not available at the Directorate, the information originally compiled and documented by the DSO is presented as such. The continued co-operation extended by the various District Authority/Head of Offices by furnishing required data is gratefully acknowledged. Suggestions for improvement of quality and coverage in the future issue of the publication are most welcome. Dated: Imphal, the 19th September, 2014 Peijonna Kamei i/c Director of Economics & Statistics Manipur MEMBER OF VIDHAN SABHA (As on the 31st January, 2013) Constituency Number Name of Assembly Constituency Name of Person Elected 1 2 3 55 Tipaimukh Dr. Chaltonlein Amo 56 Thanlon Shri. -

List of Active Cscs

SUMMARY SL NO DISTRICT NO. OF ACTIVE CSCs/VLEs 1 Bishnupur 103 2 Chandel 10 3 Tengnoupal 8 4 CCP 122 5 Pherzawl 8 6 I-E 131 7 I-W 227 8 Jiribam 8 9 Kamgjong 23 10 Kangpokpi 29 11 Noney 15 12 Tamenglong 26 13 Thoubal 143 14 Kakching 44 15 Ukhrul 57 16 Senapati 25 Total 979 LIST OF ACTIVE COMMON SERVICE CENTRES (CSCs) District :- Imphal West Active VLE List :- 227 Sl No. CSC ID VLE Name Location Block Pincode Contract No Email Id Mayang Imphal Bengoon Mamang 1 131567410018 Abdul Bari Loukok Wangoi 795132 9808803446 [email protected] 2 772427720019 Abujam Aboy Meetei Ghari Patsoi 795140 9916839160 [email protected] Ningombam Mayai Leikai 3 292772390016 Ahongshangbam Ruhikumar Singh Near Airport Wangoi 795003 8575647458 [email protected] Ningombam Mayai Leikai 4 626364450017 Akoijam Mahesh Singh Ningombam Wangoi 795003 7005761070 [email protected] Thangmeiband 5 313490140018 Ameet Kumar Ngangom Yumnam Leikai Lamphelpat 795001 8974058270 [email protected] tabungkhok 6 443327160011 Amom Haridas Meetei awang leikai Patsoi 795113 7085669405 [email protected] 7 516716320012 Angom Nishikanta Singh sekmai bazar Lamsang 795136 7085909293 [email protected] Phayeng 8 261226430015 Angom Priyokanta Umang Leikai Lamsang 795146 7629937902 [email protected] Awang Sekmai 9 519339580012 Angom Satish Singh Bazar Lamsang 795136 9555452145 [email protected] 10 156417220015 Angom Sharat Singh phoubakchao Wangoi 795132 9402967785 [email protected] Uripok Achom 11 268004390013 Angom Umakanta Singh Leikai Lamphelpat -

Districts of Manipur State

Manipur State Selected Economic Indicators. Sl. Items Ref. Year Unit Particulars No. 1. Geographical Area 2011 Census '000 Sq. Km. 22.327 2. Population 2011 Census Lakh No. 27.22 3. Density -do- Persons per 121 Sq. Km. 4. Sex Ratio -do- Females per 987 '000 Males 5. Percentage of Urban Population to -do- Percentage 43 the total population 6. Average Annual Exponential Growth 2001-2011 -do- 1.86% Rate 7. Population Below Poverty Line (As 1999-2000 -do- 28.54% per Planning Commission estimates) 8. Literacy rate : (i) Persons (ii) Male (iii) 2011 Census -do- i) 79.85% Female ii) 85.48% iii)77.15% 9. Gross State Domestic Product 2004-05 to 2010- (GSDP) at factor cost : 2011 (Q) Rs. in crore 9198.14 (i) At current prices -do- -do- 7184.09 (ii) At constant (1993-94) prices 10. Net State Domestic Product (NSDP) at factor cost -do- -do- 8228.31 (i) At current prices -do- -do- 6548.20 (ii) At constant (1993-94) prices 11. Per Capita NSDP (i) At current prices 2003-2004 Rupees 29684 (ii) At constant (1993-94) prices -do- 23298 12. Index of Agricultural Production 2002-2003 (P) - 3325 (Base: Triennium ending 1981- 82=100) 13. Total cropped area 1999-2000 Lakh hectare 1,65,787 14. Net area sown -do- -do- 1,55,232 15. Index of Industrial Production (Base : 2002-2003 (P) - 502 1993-94=100 16. Post office per lakh population 2017 (December) No. 25.75 17. All scheduled commercial banks per 2017 (December) Nos. 6.87 lakh population 18. -

The Complexities of Tribal Land Rights and Conflict in Manipur: Issues and Recommendations 2

Issue Brief – June 2017 Vol: VIII Vivekananda International Foundation Brigadier Sushil Kumar Sharma The Complexities of Tribal Land Rights and Conflict in Manipur: Issues and Recommendations 2 About the Author Brigadier Sushil Kumar Sharma, YSM, commanded a Brigade in Manipur and served as the Deputy General Officer Commanding of a Mountain Division in Assam. He has been conferred with a PhD, for his study on North-East India. He is presently posted as Deputy Inspector General of Police, Central Reserve Police Force in Delhi. http://www.vifindia.org © Vivekananda International Foundation The Complexities of Tribal Land Rights and Conflict in Manipur: Issues and Recommendations 3 The Complexities of Tribal Land Rights and Conflict in Manipur: Issues and Recommendations Abstract Land is at the center of most conflicts in Northeast India because of its importance in the life of the people of the region, particularly its tribal communities. Manipur, the Land of Jewels, has been besieged with conflicts on issues ranging from exclusivity, integration and governance. All these have stemmed from the basic dispute over the land. The tribal people of the hills and the valley based people have different approaches and laws towards governance of their land which they consider their exclusive territories. This study attempts to track the issues concerning the land rights of various people in the state and the ethnic conflict surrounding it and attempts to identify land issues that are leading to ethnic conflict in Manipur and tries to address the issue of conflict and make suggestions thereof. Introduction The Study Over the landscape of the history of mankind that we know, since times which have been chronicled there has always been conflict amongst human beings to possess, cherish and control land. -

BOARD of SECONDARY EDUCATION, MANIPUR School-Wise Pass Percentage for H.S.L.C

BOARD OF SECONDARY EDUCATION, MANIPUR School-wise pass percentage for H.S.L.C. Examination, 2019 1-Government Stu. 1st 2nd 3rd Total Sl. No. Code Name of School Pass% App. Div. Div. Div. Passed 1 36091 ABDUL ALI HIGH MADRASSA, LILONG 37 4 19 0 23 62.16 2 28331 AHMEDABAD HIGH SCHOOL, JIRIBAM 48 0 7 3 10 20.83 3 98741 AIMOL CHINGNUNGHUT HIGH SCHOOL, CHANDEL 50 4 19 0 23 46 4 88381 AKHUI HIGH SCHOOL, TAMENGLONG 5 1 4 0 5 100 5 21201 ANANDA SINGH HR. SECONDARY ACADEMY, IMPHAL24 3 7 0 10 41.67 6 29121 ANDRO HIGH SCHOOL, ANDRO IMPHAL EAST DISTRICT9 0 5 1 6 66.67 7 79451 AWANG LONGA KOIRENG GOVT. HIGH SCHOOL, LONGA13 KOIRE 1 2 0 3 23.08 8 21211 AWANG POTSANGBAM HIGH SCHOOL, AWANG POTSANGBAM21 0 2 1 3 14.29 9 21221 AZAD HIGH SCHOOL, YAIRIPOK 84 27 55 0 82 97.62 10 18271 BENGOON HIGHER SECONDARY SCHOOL, MAYANG IMPHAL30 4 20 4 28 93.33 11 10031 BHAIRODAN MAXWELL HINDI HIGH SCHOOL, IMPHAL19 1 2 1 4 21.05 12 79431 BISHNULAL HIGH SCHOOL, CHARHAJARE 50 8 37 2 47 94 13 43101 BISHNUPUR HIGH SCHOOL , BISHNUPUR 31 7 14 1 22 70.97 14 43111 BISHNUPUR HIGHER SECONDARY SCHOOL, BISHNUPUR68 0 5 1 6 8.82 15 21231 BOROBEKRA HR. SEC. SCHOOL, JIRIBAM 51 1 11 1 13 25.49 16 63981 BUKPI HIGH SCHOOL, B.P.O. BUKPI, CCPUR 16 0 5 0 5 31.25 17 79221 BUNGTE CHIRU HIGH SCHOOL, SADAR HILLS 7 0 1 0 1 14.29 18 21241 C.C. -

Manipur-17.05.21- Order on Extension of Curfew from 18.05.2021 to 28.05.2021.Pdf

No. H-1601/6/2020-HD GOVERNMENT OF MANIPUR HOME DEPARTMENT ORDERS Imphal, the 17th May, 2021 1. Whereas, the Chairperson, State Executive Committee of the State Disaster Management Authority in exercise of the powers conferred under Section 20(2)(a) of the Disaster Management Act, 2005 had issued orders dated 07/05/2021 imposing "Curfew" and the activities to restricting only few essential services in the Districts of Imphal West, Imphal East, Bishnupur, Thoubal, Kakching, Chuachandpur and Ukhrul in view of the exponential increase in the number of infections in these districts which was followed by another order dated 11/05/2021 which allowed limited activities to mitigate the hardships of the public. 2. Whereas, the virulence of the Covid-19 virus continues unabated and the need for stringent measures to check physical contact amongst people still existts. 3. Therefore, in exercise of the powers conferred under Section 20(2)(a) of the Disaster Management Act, 2005 the undersigned in his capacity as Chairperson, State Executive Committee of the State Disaster Management Authority, hereby extends the CURFEW" in the Districts of Imphal West, Imphal East, Bishnupur, Thoubal, Kakching, Churachandpur and Ukhrul with effect from 18/05/2021 to 28/05/2021 as per details below: I. List of permitted activities. All healthcare facilities, including animal healthcare, hospitals, clinics, nursing homes and movement of healthcare workers. i. All pharmacies, including those selling veterinary medicines. ii. All persons going for COVID-19 vaccination, COVID testing and medical emergencies are exempted. iv. All employees and personal staff working in Media, Power, Fire Service, PHED, CAFPD, Home, Health, Relief & DM, Forest, Environment & Climate Change, Finance and Treasuries and Police departments and District Administration are exempted (all other offices to remain closed).