Downloaded Into Her Brain — Every One Except Caroline’S

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CINDERELLA Curriculum Connections California Content Standards Kindergarten Through Grade 12

San Francisco Operaʼs Rossiniʼs CINDERELLA Curriculum Connections California Content Standards Kindergarten through Grade 12 LANGUAGE ARTS WORD ANALYSIS, FLUENCY, AND VOCABULARY DEVELOPMENT Phonics and Phonemic Awareness: Letter Recognition: Name the letters in a word. Ex. Cinderella = C-i-n-d-e-r-e-l-l-a. Letter/Sound Association: Name the letters and the beginning and ending sound in a word. C-lorind-a Match and list words with the same beginning or ending sounds. Ex. Don Ramiro and Dandini have the same beginning letter “D” and sound /d/; but end with different letters and ending sounds. Additional examples: Don Ramiro, Don Magnifico, Alidoro; Cinderella, Clorinda. Syllables: Count the syllables in a word. Ex.: Cin-der-el-la Match and list words with the same number of syllables. Clap out syllables as beats. Ex.: 1 syllable 2 syllables 3 syllables bass = bass tenor = ten-or soprano = so-pra-no Phoneme Substitution: Play with the beginning sounds to make silly words. What would a “boprano” sound like? (Also substitute middle and ending sounds.) Ex. soprano, boprano, toprano, koprano. Phoneme Counting: How many sounds in a word? Ex. sing = 4 Phoneme Segmentation: Which sounds do you hear in a word? Ex. sing = s/i/n/g. Reading Skills: Build skills using the subtitles on the video and related educator documents. Concepts of Print: Sentence structure, punctuation, directionality. Parts of speech: Noun, verb, adjective, adverb, prepositions. Vocabulary Lists: Ex. Cinderella, Opera glossary, Music and Composition terms Examine contrasting vocabulary. Find words in Cinderella that are unfamiliar and find definitions and roots. Find the definitions of Italian words such as zito, piano, basta, soto voce, etcetera, presto. -

PDF Download Cinder Edna Pdf Free Download

CINDER EDNA PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Ellen Jackson | 32 pages | 04 Nov 1999 | HarperCollins Publishers Inc | 9780688162955 | English | New York, NY, United States Cinder Edna PDF Book He goes on the search for Edna, but without using the loafer. In this lesson the students compare and contrast the two characters in the original Cinderella and Cinder Edna. Marrying someone after knowing her for only one evening is advisable if based on mutual unattractive This was given to me as a gift. One of two new takes on a tale that feminists justly find problematic see also Minters, below. The text is frequently only on one page, while illustrations take up the rest of the page and the page next to it. When you know how long it takes, and your parents know you can do the job well, negotiate a price. Cinder Edna and Rupert have decided to write a book together. It is definitely a funny story to read with children who are familiar with the classic Cinderella story because it takes those magical elements and discusses how they would play out in real life. What color is your hair? When I do that I ask a learner to say, "I agree that they are similar because they both were over worked, and I want to add that Cinderella was beautiful, but Edna was not. An alternative version to Cinderella with a 'Great Gatsby' type setting. Forget practicality. Answer: Randolph keeps turning his head so Cinder Edna can see his profile thinking that will impress her. Mostly I review the troops and sit around on the throne looking brave and wise. -

Damsel in Distress Or Princess in Power? Traditional Masculinity and Femininity in Young Adult Novelizations of Cinderella and the Effects on Agency

Brigham Young University BYU ScholarsArchive Theses and Dissertations 2020-12-09 Damsel in Distress or Princess in Power? Traditional Masculinity and Femininity in Young Adult Novelizations of Cinderella and the Effects on Agency Rylee Carling Brigham Young University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/etd Part of the Education Commons BYU ScholarsArchive Citation Carling, Rylee, "Damsel in Distress or Princess in Power? Traditional Masculinity and Femininity in Young Adult Novelizations of Cinderella and the Effects on Agency" (2020). Theses and Dissertations. 8758. https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/etd/8758 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Damsel in Distress or Princess in Power? Traditional Masculinity and Femininity in Young Adult Novelizations of Cinderella and the Effects on Agency Rylee Carling A thesis submitted to the faculty of Brigham Young University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Paul Ricks, Chair Terrell Young Dawan Coombs Stefinee Pinnegar Department of Teacher Education Brigham Young University Copyright © 2020 Rylee Carling All Rights Reserved ABSTRACT Damsel in Distress or Princess in Power? Traditional Masculinity and Femininity in Young Adult Novelizations of Cinderella and the Effects on Agency Rylee Carling Department of Teacher Education, BYU Master of Arts Retellings of classic fairy tales have become increasingly popular in the past decade, but little research has been done on the novelizations written for a young adult (YA) audience. -

ON INTERNALIZED OPPRESSION and SEXUALIZED VIOLENCE in COLLEGE WOMEN Marina Leigh Costanzo

University of Montana ScholarWorks at University of Montana Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Graduate School Professional Papers 2018 ON INTERNALIZED OPPRESSION AND SEXUALIZED VIOLENCE IN COLLEGE WOMEN Marina Leigh Costanzo Let us know how access to this document benefits ouy . Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd Recommended Citation Costanzo, Marina Leigh, "ON INTERNALIZED OPPRESSION AND SEXUALIZED VIOLENCE IN COLLEGE WOMEN" (2018). Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers. 11264. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd/11264 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at ScholarWorks at University of Montana. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at University of Montana. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ON INTERNALIZED OPPRESSION AND SEXUALIZED VIOLENCE IN COLLEGE WOMEN By MARINA LEIGH COSTANZO B.A., University of Washington, Seattle, WA, 2010 M.A., University of Colorado, Colorado Springs, CO, 2013 Dissertation presented in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctorate of Philosophy in Clinical Psychology The University of Montana Missoula, MT August 2018 Approved by: Scott Whittenburg, Dean of The Graduate School Graduate School Christine Fiore, Chair Psychology Laura Kirsch Psychology Jennifer Robohm Psychology Gyda Swaney Psychology Sara Hayden Communication Studies INTERNALIZED OPPRESSION AND SEXUALIZED VIOLENCE ii Costanzo, Marina, PhD, Summer 2018 Clinical Psychology Abstract Chairperson: Christine Fiore Sexualized violence on college campuses has recently entered the media spotlight. One in five women are sexually assaulted during college and over 90% of these women know their attackers (Black et al., 2011; Cleere & Lynn, 2013). -

Structural Sexism and Health in the United States by Patricia A. Homan

Structural Sexism and Health in the United States by Patricia A. Homan Department of Sociology Duke University Date:_______________________ Approved: ___________________________ Linda K. George, Co-Supervisor ___________________________ Scott M. Lynch, Co-Supervisor ___________________________ Jen’nan G. Read ___________________________ Laura S. Richman ___________________________ Tyson H. Brown Dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Sociology in the Graduate School of Duke University 2018 ABSTRACT Structural Sexism and Health in the United States by Patricia A. Homan Department of Sociology Duke University Date:_______________________ Approved: ___________________________ Linda K. George, Co-Supervisor ___________________________ Scott M. Lynch, Co-Supervisor ___________________________ Jen’nan G. Read ___________________________ Laura S. Richman ___________________________ Tyson H. Brown An abstract of a dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Sociology in the Graduate School of Duke University 2018 Copyright by Patricia A. Homan 2018 Abstract In this dissertation, I seek to begin building a new line of health inequality research that parallels the emerging structural racism literature by developing theory and measurement for the new concept of structural sexism and examining its relationship to health. Consistent with contemporary theories of gender as a multilevel social system, I conceptualize and measure structural sexism as systematic gender inequality in power and resources at the macro-level (U.S. state), meso-level (marital dyad), and micro-level (individual). Through a series of quantitative analyses, I examine how various measures of structural sexism affect the health of men, women, and infants in the U.S. -

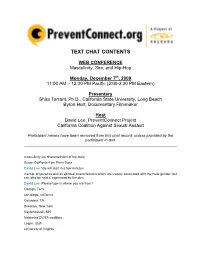

Text Chat Contents

TEXT CHAT CONTENTS WEB CONFERENCE Masculinity, Sex, and Hip-Hop Monday, December 7th, 2009 11:00 AM – 12:30 PM Pacific (2:00-3:30 PM Eastern) Presenters Shira Tarrant, Ph.D., California State University, Long Beach Byron Hurt, Documentary Filmmaker Host David Lee, PreventConnect Project California Coalition Against Sexual Assault Participant names have been removed from this chat record, unless provided by the participant in text. masculinity are characteristics of the male Susan DelPonte from Penn State David Lee: We will start in a few minutes mental, physical as well as spiritual characteristics which are usually associated with the male gender, but can also be held & expressed by females David Lee: Please type in where you are from? Georgia Tech san diego, california Columbia, TN Brooklyn, New York Naytahwaush, MN Nebraska DV/SA coalition Logan, Utah University of Virginia Text Chat Contents Fargo, ND Virginia Beach, VA Humboldt County, CA Austin, TX Atlanta Georgia Spirit Lake, Iowa Humboldt and Del Norte Counties Fairfax Virginia Jennifer Thomas, Atlanta Georgia Twin Cities, MN Harrisonburg, VA Tampa, FL Durango, CO David Lee: And what organization are you with? Grand Forks, ND Fayetteville, Arkansas and Jacquie Marroquin from Haven Women's Center of Stanislaus Marsha Landrith: Lakeview, Oregon Norfolk, VA DOVE Program Human Services Inc Crisis Center of Tampa Bay Nancy Boyle: Rape & Abuse Crisis Center, Fargo ND Patti Torchia, Springfield, IL Rape and Abuse Crisis Center, Fargo, ND North Coast Rape Crisis Team, Humboldt/Del Norte CA Local health department CAPSA Domestic violence/rape advocacy organization United States Naval Academy, Annapolis, MD Patricia Maarhuis & Ginny Hauser: WSU Pullman WA GA Commission on Family Violence Sexual Assault Services Org. -

MEDIA LITERACY THROUGH INTERTEXTUAL ANALYSIS a Project Presented to the Faculty of the Department of Graduate and Professional S

MEDIA LITERACY THROUGH INTERTEXTUAL ANALYSIS A Project Presented to the faculty of the Department of Graduate and Professional Studies in Education California State University, Sacramento Submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS in Education (Behavioral Sciences Gender Equity Studies) by Danielle Norman SUMMER 2020 © 2020 Danielle Norman ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii MEDIA LITERACY THROUGH INTERTEXTUAL ANALYSIS A Project by Danielle Norman Approved by: __________________________________, Committee Chair Sherrie Carinci, Ed.D. ____________________________ Date iii Student: Danielle Norman I certify that this student has met the requirements for format contained in the University format manual, and this project is suitable for electronic submission to the library and credit is to be awarded for the project. __________________________, Department Chair ___________________ Carlos Nevarez, Ph.D. Date Department of Graduate and Professional Studies in Education iv Abstract of MEDIA LITERACY THROUGH INTERTEXTUAL ANALYSIS by Danielle Norman Using a critical pedagogy perspective, this project aims to integrate media literacy within elementary classrooms. Incorporating intertextual analysis of a traditional and non-traditional fairy tale will provide students with the opportunity to engage in the active process of understanding socially-constructed hegemony. The curriculum encompasses three academic weeks and is designed to be conducted within a small group setting. This project is tailored for grades four through siX, with the intention of raising media literacy consciousness with a focus on gender identity construction and ideas. The traditional fairy tale is an original interpretation of Cinderella. This story contains the consistent stereotypical messages that have been disseminated through multiple influential, male authors over the past 400 years. -

To Whom the Shoe Fits: Cinderella As a Cultural Phenomenon in the Czech and Norwegian Context

Masaryk University Faculty of Arts Department of Germanic, Nordic and Dutch Studies To Whom the Shoe Fits: Cinderella as a Cultural Phenomenon in the Czech and Norwegian Context 2020 Mgr. Adéla Ficová Masaryk University Faculty of Arts Department of Germanic, Nordic and Dutch Studies Norwegian Language and Literature Mgr. Adéla Ficová To Whom the Shoe Fits: Cinderella as a Cultural Phenomenon in the Czech and Norwegian Context M.A. Thesis Supervisor: Mgr. Karolína Stehlíková, Ph.D. 2020 2 Statutory Declaration I hereby declare that I have written the submitted Master Thesis To Whom the Shoe Fits: Cinderella as a Cultural Phenomenon in the Czech and Norwegian Context independently. All the sources used for the purpose of finishing this thesis have been adequately referenced and are listed in the Bibliography. In Brno, 12 May 2020 ....................................... Mgr. Adéla Ficová 3 Acknowledgements I would like to express my sincere gratitude to my supervisor Mgr. Karolína Stehlíková, Ph.D., for her helpful guidance and valuable advices and shared enthusiasm for the topic. I also thank my parents and my friends for their encouragement and support. 4 Table of contents 1 Introduction ..................................................................................................................................... 6 1.1 Literature review ..................................................................................................................... 8 2 Historical genesis of the Cinderella fairy tale ................................................................................ -

O ALTO E O BAIXO NA ARQUITETURA.Pdf

UNIVERSIDADE DE BRASÍLIA FACULDADE DE ARQUITETURA E URBANISMO O ALTO E O BAIXO NA ARQUITETURA Aline Stefânia Zim Brasília - DF 2018 1 ALINE STEFÂNIA ZIM O ALTO E O BAIXO NA ARQUITETURA Tese apresentada ao Programa de Pós-Graduação em Arquitetura e Urbanismo da Faculdade de Arquitetura da Universidade de Brasília como requisito parcial à obtenção do grau de Doutora em Arquitetura. Área de Pesquisa: Teoria, História e Crítica da Arte Orientador: Prof. Dr. Flávio Rene Kothe Brasília – DF 2018 2 TERMO DE APROVAÇÃO ALINE STEFÂNIA ZIM O ALTO E O BAIXO DA ARQUITETURA Tese aprovada como requisito parcial à obtenção do grau de Doutora pelo Programa de Pesquisa e Pós-Graduação da Faculdade de Arquitetura e Urbanismo da Universidade de Brasília. Comissão Examinadora: ___________________________________________________________ Prof. Dr. Flávio René Kothe (Orientador) Departamento de Teoria e História em Arquitetura e Urbanismo – FAU-UnB ___________________________________________________________ Prof. Dr. Fernando Freitas Fuão Departamento de Teoria, História e Crítica da Arquitetura – FAU-UFRGS ___________________________________________________________ Prof. Dra. Lúcia Helena Marques Ribeiro Departamento de Teoria Literária e Literatura – TEL-UnB ___________________________________________________________ Prof. Dra. Ana Elisabete de Almeida Medeiros Departamento de Teoria e História em Arquitetura e Urbanismo – FAU-UnB ___________________________________________________________ Prof. Dr. Benny Schvarsberg Departamento de Projeto e Planejamento – FAU-UnB Brasília – DF 2018 3 AGRADECIMENTOS Agradeço a todos que compartilharam de alguma forma esse manifesto. Aos familiares que não puderam estar presentes, agradeço a confiança e o respeito. Aos amigos, colegas e alunos que dividiram as inquietações e os dias difíceis, agradeço a presença. Aos que não puderam estar presentes, agradeço a confiança. Aos professores, colegas e amigos do Núcleo de Estética, Hermenêutica e Semiótica. -

Analysis of Cinderella Motifs, Italian and Japanese

Analysis of Cinderella Motifs, Italian and Japanese By C h ie k o I r ie M u lh e r n University of Illinois at Urbana—Champaign I ntroduction The Japanese Cinderella cycle is a unique phenomenon. It is found in the medieval literary genre known as otogizoshi 御 伽 草 子 (popular short stories that proliferated from the 14th to the mid-17th centuries). These are literary works which are distinguished from transcribed folk tales by their substantial length and scope; sophistication in plot struc ture, characterization, and style; gorgeous appearance in binding and illustration; and wide circulation. The origin, date, authorship, reader ship, means of circulation, and geographic distribution of the otogizoshi tales, which include some four hundred,remains largely nebulous. Particularly elusive among them is the Cinderella cycle, which has no traceable predecessors or apparent progeny within the indigenous or Oriental literary traditions. In my own previous article, ‘‘ Cinderella and the Jesuits ” (1979), I have established a hypothesis based on analysis of the tales and a com parative study of the Western Cinderella cycle. Its salient points are as follows: 1 . The Japanese tales show an overwhelming affinity to the Italian cycle. 2. The Western influence is traced to the Japanese-speaking Italian Jesuits stationed in Japan during the heyday of their missionary activity between 1570 and 1614; and actual authorship is attributable to Japa nese Brothers who were active in the Jesuit publication of Japanese- language religious and secular texts. 3. Their primary motive in writing the Cinderella tales seems to have been to proselytize Christianity and to glorify examplary Japanese Asian Folklore Studiest V ol.44,1985, 1-37. -

Film. It's What Jews Do Best. Aprll 11-21 2013 21ST

21ST TORONTO JEWISH FILM FESTIVAL APRIL 11-21 2013 WWW.TJFF.COM FILM. It’S WHAT JEWS DO BEST. DRAMAS OVERDRIVE AD COMEDIES DOCUMENTARIES BIOGRAPHIES ARCHIVAL FILMS ARCHIVAL SHORT FILMS SHORT Proudly adding a little spark to the Toronto Jewish Film Festival since 2001. overdrivedesign.com 2 Hillel Spotlight on Israeli Films Spotlight on Africa Israel @ 65 Free Ticketed Programmes CONTENTS DRAMAS 19 COMEDIES 25 DOCUMENTARIES 28 BIOGRAPHIES 34 ARCHIVAL FILMS 37 SHORT FILMS 38 4 Schedule 15 Funny Jews: 7 Comedy Shorts 42 Patron Circle 6 Tickets 15 REEL Ashkenaz @ TJFF 43 Friends and Fans 7 Artistic Director’s Welcome 16 Talks 44 Special Thanks 8 Co-Chairs’ Message 17 Free Family Screenings 44 Nosh Donors 9 Programme Manager’s Note 18 Opening / Closing Night Films 44 Volunteers 10 Programmers’ Notes 19 Dramas 46 Sponsors 12 David A. Stein Memorial Award 25 Comedies 49 Advertisers 13 FilmMatters 28 Documentaries 67 TJFF Board Members and Staff 13 Hillel Spotlight on Israeli Film 34 Biographies 68 Films By Language 14 Spotlight on Africa 37 Archival Films 70 Films By Theme / Topic 14 Israel @ 65 38 Short Films 72 Film Index APRIL 11–21 2013 TJFF.COM 21ST ANNUAL TORONTO JEWISH FILM FESTIVAL 3 SCHEDULE • Indicates film has additional screening(s).Please Note: Running times do not include guest speakers where applicable. Thursday April 11 Monday April 15 8:30 PM BC 92 MIN CowJews and Indians: How Hitler 1:00 PM ROM 100 MIN • Honorable Ambassador w/ Delicious Scared My Relatives and I Woke up Peace Grows in a Ugandan in an Iroquois Longhouse —Owing -

If You Like Fairy Tales the Last Unicorn by Peter S. Beagle (Original) the Amaranth Enchantment by Julie Berry (Original) Serend

If You Like Fairy Tales The Last Unicorn by Peter S. Beagle (original) The Amaranth Enchantment by Julie Berry (original) Serendipity Market by Penny Blubaugh (mix of several fairy tales) Sisters Grimm series by Michael Buckley (mix of several fairy tales) A Curse Dark as Gold by Elizabeth C. Bunce (Rumplestiltskin) Further Tales series by P.W. Catanese (several fairy tales) Runaway Princess and Runaway Dragon by Kate Coombs (original) Entwined by Heather Dixon (Twelve Dancing Princesses) Into the Wild and Out of the Wild by Sarah Beth Durst (mix of several fairy tales) Fortune’s Folly by Deva Fagan (mix of several fairy tales) Once Upon a Marigold and Twice Upon a Marigold by Jean Ferris (original) Shadow Spinner by Susan Fletcher (Arabian Nights) Reckless by Cornelia Funke (mix of several Grimm fairy tales) Stardust by Neil Gaiman (original) Into the Woods and Out of the Woods by Lyn Gardner (mix of several fairy tales) Princess of the Midnight Ball and Princess of Glass by Jessica Day George (Twelve Dancing Princesses and Cinderella) Sun and Moon, Ice and Snow by Jessica Day George (East of the Sun, West of the Moon) Book of a Thousand Days by Shannon Hale (Maid Maleen) Rapunzel’s Revenge and Calamity Jack by Shannon and Dean Hale (Rapunzel and Jack and the Beanstalk) – graphic novel Goose Girl by Shannon Hale (Goose Girl) Princess Curse by Merrie Haskell (Twelve Dancing Princesses/Beauty and the Beast) Goose Chase by Patrice Kindl (Goose Girl) Keturah and Lord Death by Martine Leavitt Cinder and Ella by Melissa Lemon (Cinderella)