Municipal Politics, Court Sympathy and Housing Rights: a Post-Mortem of Displacement and Resettlement Under the Sabarmati Riverfront Project, Ahmedabad

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Disastrous Condition of the Sabarmati River

PRESS RELEASE 27 March 2019 Disastrous Condition of the Sabarmati River - Release of report on joint investigations by Paryavaran Suraksha Samiti and Gujarat Pollution Control Board, of the pollution levels in the prime water source of Ahmedabad District. The Sabarmati River in the Ahmedabad City stretch, before the Riverfront, is dry and within the Riverfront Project stretch, is Brimming with Stagnant Water. In the last 120 kilometres, before meeting the Arabian Sea, it dead comprises of just industrial effluent and sewage. On 12 March 2019, the Regional Officers Mr Tushar Shah and Ms Nehalben Ajmera of Gujarat Pollution Control Board, Rohit Prajapati and Krishnakant of Paryavaran Suraksha Samiti, Social Activist Mudita Vidrohi of Ahmedabad, Subodh Parmar, Lawyer of Gujarat High Court, conducted a joint investigation. This was conducted in the context of implementation of the Order, dated 22.02.2017, of the Supreme Court in Writ Petition (Civil) No. 375 of 2012 (Paryavaran Suraksha Samiti & Anr V/s Union of India & Ors) about the status of industrial effluent and sewerage discharge into the Sabarmati River stretch of Ahmedabad District. The investigation reports are shocking and reveal the disastrous condition of Sabarmati River in and around Ahmedabad District and about 120 kilometres downstream. Sabarmati River no longer has any fresh water when it enters the city of Ahmedabad. The Sabarmati Riverfront has merely become a pool of polluted stagnant water while the river, downstream of the riverfront, has been reduced to a channel carrying effluents from industries from Naroda, Odhav Vatva, Narol and sewerage from Ahmedabad city. The drought like condition of the Sabarmati River intensified by the Riverfront Development has resulted in poor groundwater recharge and increased dependency on the already ailing Narmada River. -

INTRODUCTION Water Is Super Abundant on the Planet As a Whole

INTRODUCTION Water is super abundant on the planet as a whole, but fresh potable water is not always available for human or ecosystem use. The importance of water is underscored by the fact that many great civilizations in the past sprang up along or near water bodies and most developmental activities are still dependent upon them. The development of water resources has often been used as yardstick for socioeconomic and health status of many nations worldwide. However, pollution of water often been neglected the benefits obtained from the development of these water resources. Rivers have always been the most important fresh water resources; river water finds multiple uses in every sector of development like agriculture, industry, transportation, aquaculture, public water supply etc. but surface waters are most exposable to pollution due to their accessibility for disposal of wastewaters. Huge loads of waste from industries, domestic sewage & agricultural practices find their way into rivers, resulting in large scale deterioration of the water quality. The Sabarmati River arises in the Aravalli Hills, which roughly mark the Western boundary of Udaipur District, i.e. Mount Abu area, and flows in a South-Westerly direction. It is approximately 371 km in length. The main tributaries of the Sabarmati River are Wakal, the Harnay, the Hathimati, the Vatrak, the Meshwa & the Sei Nadi, which also flow South- Westwards in courses generally parallel to the Sabarmati River, up to their confluence with the river (in Gujarat). And finally it empties in the Gulf of Cambay of Arabian Sea. The Sabarmati River Basin is situated in the mid-Sothern part of Rajasthan, between latitudes 23025’ & 24055’ and longitudes 73000’ & 73048’. -

Floating Restaurant at Sabarmati Riverfront

Development of Floating restaurant at Sabarmati riverfront Tourism Government of Gujarat Contents Project Concept 3 Market Potential 4 Growth Drivers 5 Gujarat – Competitive Advantage 6 Project Information 8 - Location/ Size - Key Players/ Machinery Suppliers - Infrastructure Availability/ Connectivity - Raw Material/ Manpower - Key Considerations Project Financials 13 Approvals & Incentives 14 Key Department Contacts 15 Page 2 Project Concept About riverside floating restaurant A riverside restaurant or a floating restaurant is usually a restaurant built on a large flat steel barge floating on water. Some times retired ships are also refurbished and given a second term as a floating restaurant. Some of the floating restaurants in India are- 1. Majastique-1 operated by Majas Travels, Tours and Logistics at Kochi 2. Flor Do Mar operated at Morjim Beach, Goa A revolving restaurant or rotating restaurant on the other hand is usually a tower based restaurant eating space designed to rest on the top of a wide spherical rotating base that operates as a large turning table. The building remains stationary and the diners are seated on the revolving floor with all the other basic restaurant features in place. The main aim of such restaurant is to provide a scenic view to its diners from a height. About Sabarmati riverfront Sabarmati river has been an essential component in of daily life in Ahmedabad since when the city was established in 1411 along the river side. Apart from being an essential source of water, it provides a view of cultural activities and historic significance of various events. During the dry seasons, the fertile river side became a good farming land. -

Sabarmati Riverfront Development: an Exercise in 'High-Modernism'?

I.S.RIVERS 2018 Sabarmati Riverfront Development: An Exercise in ‘High-Modernism’? A la reconquête des berges du fleuve Sabarmati : un exercice de "haut-modernisme" ? Krishnachandran Balakrishnan Indian Institute for Human Settlements, Bangalore, India ([email protected]) RÉSUMÉ En utilisant l’exemple de l’aménagement des berges du fleuve Sabarmati (Sabarmati Riverfront Development Project - SRDP) à Ahmedabad, cet article illustre comment la catégorie conceptuelle de berge, déjà présente plus particulièrement à Londres et Paris, a inspiré l’imagination de ce que devrait être une rivière urbaine en Inde. Cet article s’attache à revoir l’étendue du projet pour conformer une rivière alimentée par la mousson à la catégorie conceptuelle prédéfinie de berge. L'argumentaire développé dans l’article est que le SRDP peut être vu comme une illustration de haut-modernisme comme l’indique James Scott – à la fois en termes d’ordre visuel qu’il s’efforce de créer et en termes de recours au concept simpliste d’écologie et d’hydrologie des rivières. Cet article conclut avec une discussion sur l’utilité des professionnels de la conception architecturale, urbaine et paysagère de comprendre les spécificités locales des écosystèmes et sociétés et d’utiliser le design comme un processus capable d’aller au-delà des catégories spatiales et conceptuelles simplistes. ABSTRACT Using the case of the Sabarmati Riverfront Development Project (SRDP) in Ahmedabad, this paper illustrates how the conceptual category of the ‘riverfront’, as seen in London and Paris in particular, has shaped the imagination of what an urban river ‘should’ be in India. The paper examines the lengths to which the project goes to fit a monsoon fed river-scape into this predefined conceptual category of a ‘riverfront’. -

Sabarmati Riverfront Development Project

SABARMATI RIVERFRONT DEVELOPMENT PROJECT A Multidimensional Environmental Improvement and Urban Rejuvenation Project … one of the most innovative projects towards urban regeneration in the world to make the city livable & sustainable (KPMG ) SABARMATI RIVER and AHMEDABAD The River Sabarmati flows from north to south splitting Ahmedabad into almost two equal parts. For many years, it has served as a water source and provided almost no formal recreational space for the city. As the city has grown, the Sabarmati river had been abused and neglected and with the increased pollution was posing a major health and environmental hazard to the city. The slums on the riverbank were disastrously flood prone and lack basic infrastructure services. The River became back of the City and inaccessible to the public Ahmedabad and the Sabarmati :1672 Sabarmati and the Growth of Ahmedabad Sabarmati has always been important to Ahmedabad As a source for drinking water As a place for recreation As a place to gather Place for the poor to build their hutments Place for washing and drying clothes Place for holding the traditional Market And yet, Sabarmati was abused and neglected Sabarmati became a place Abuse of the River to dump garbage • Due to increase in urban pressures, carrying capacity of existing sewage system falling short and its diversion into storm water system releasing sewage into the River. Storm water drains spewed untreated sewage into the river • Illegal sewage connections in the storm water drains • Open defecation from the near by human settlements spread over the entire length. • Discharge of industrial effluent through Nallas brought sewage into some SWDs. -

SRFDCL Presentation

Sabarmati Riverfront Reconnecting Ahmedabad to its River Sabarmati Riverfront A Catalyst for Ahmedabad’s Economic Growth Sabarmati Riverfront Reconnecting Ahmedabad to its River Urbanization is the defining phenomenon of the 21st century Globally, an unprecedented Pace & Scale of Urbanization Sabarmati Riverfront Reconnecting Ahmedabad to its River For the first time in history, more than half of the world’s population lives in cities 90% of urban growth is taking place in the developing world UN World Population Prospects: The 2006 Revision and World Urbanization Prospects Cities are Engines of Economic Growth •Economic growth is associated with Sabarmati Riverfront Reconnecting Ahmedabad to its River agglomeration • No advanced country has achieved high levels of development w/o urbanizing •Density is crucial for efficiency in service delivery and key to attracting investments due to market size •Urbanization contributes to poverty reduction UN World Population Prospects: The 2006 Revision and World Urbanization Prospects Transformational Urbanism Sabarmati Riverfront Reconnecting Ahmedabad to its River 1. The logic of economic geography 2. Well-planned urban development – a pillar of economic growth Sabarmati Riverfront Reconnecting Ahmedabad to its River Living close to work can encourage people to walk and cycle or use public transport. Makes the private vehicle less popular. Makes the city healthy Advantage Gujarat Sabarmati Riverfront Reconnecting Ahmedabad to its River 6% of India’s Geographical 5% of India’s population: Area: -

Final Draft City & Society Special Issue “Betrayal in the City: Urban

Final draft City & Society Special issue “Betrayal in the city: Urban development in the North and South,” edited by Marie Kolling and Martijn Koster From Third-Class to World-Class Citizens: Claiming Belonging, Countering Betrayal in the Margins of Ahmedabad1 Jelena Salmi University of Helsinki 1 Abstract This paper ethnographically explores the repercussions of the large-scale displacement and resettlement of slum-dwellers in the city of Ahmedabad, India, where state-sponsored urban development aimed at the creation of a slum-free world-class city is strongly personified around the figure of Prime Minister Narendra Modi. Based on ten months’ fieldwork in the slum resettlement site of Sadbhavna Nagar in 2015–2016, I explore the intricacies of betrayal resulting from world-class city making. First, I suggest that infrastructure interventions and futuristic imaginaries invoked dreams of a better future among the poor, but resulted in a sense of having been betrayed by both Modi and the state when people were physically and discursively excluded from the world-class city. Second, I demonstrate how resettled people have engaged in micro-level practices of betrayal by mobilizing middle-class “nuisance talk” (Ghertner 2012) to denigrate their new, unwanted neighbors. I argue that the perceived betrayal by the state trickles down and translates into a betrayal of neighbors in the resettlement site, reinforcing the pre-existing inequalities of caste and religion among the urban poor [Displacement; Urban Development; World-Class City; Resettlement; India]. 2 He [Modi] threw us here. Everyone thought he’d do good for Gujarat, he was supposed to do good for the poor, but for your [foreigners’] riverfront,2 he divided us [into different resettlement sites]. -

Ahmedabad Residential Real Estate Overview March 2012 TABLE of CONTENTS

Ahmedabad Residential Real Estate Overview March 2012 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. Executive Summary 3 2. Ahmedabad Fact File 4 3. Infrastructure 6 4. Culture of the city 7 5. Gandhinagar–Twin city of Gujarat 8 6. Ahmedabad Real Estate 10 7. Ahmedabad City Map 11 8. Central Ahmedabad 12 9. North Ahmedabad 14 10. South Ahmedabad 15 11. East Ahmedabad 16 12. West Ahmedabad 17 13. Location Attractiveness Index 19 14. Disclaimer 20 2 Executive Summary The ‘Ahmedabad Residential Real Estate Overview’ provides a comprehensive insight into the key macro and micro trends emerging in the residential real estate market of Ahmedabad. The ICICI Home Finance Company team undertook a detailed city survey and presented below are the key highlights of the report. The development of residential townships, malls, office spaces and flyovers are some of the growth stimulators changing the cityscape of Ahmedabad. Maximum activity in terms of planned residential, commercial and retail development can be witnessed in this western micro market of Ahmedabad. Residential real estate of Ahmedabad is dominated by private players and the market is also heavily driven by an active investor base, with most of the participants plowing capital market profits into the real estate markets. Real estate scenario in the city has been stagnant in the near term, owing to the increased home loan rates and slowdown in the equity markets. However, in the long term, we see an appreciation of 9–10% YoY in property prices over the next 5 years, due to the inherent demand and the continued pace of infrastructure developments in the city. -

Sabarmati River Front Development Project

Sabarmati River Front Development Project Why in news? Recently Ahmedabad Municipal Corporation set aside Rs 1,050 crore for the phase-2 of the Sabarmati River Front Development project (SRFD). How much land has been reclaimed for the development? In the first phase of the project, 204 hectares have been reclaimed along the 11-km stretch of the Sabarmati Riverfront. This land excludes the Central Business District (CBD) area of 126 hectares and the reclaimed land includes road and the land to be developed. The main considerations in allocating the reclaimed land are the use of existing land along the river, location and configuration of land available, its potential for development. The development will witness pedestrian-friendly roads by requiring buildings to align with the road side. How will Sabarmati Riverfront Development (SRFD) act as a catalyst for the CBD? The SRFD offers incentive of a higher (three times more) Floor Space Index (FSI) that will change the skyline of the city. The plots under SRFD phase 1 will permit buildings from 6 to 22 floors that will offer a total of 16.4 lakh square metre of saleable area in phases. But the permissible height of buildings in the CBD would depend upon the road width. The Local Area Plan proposes to revive this central area by leveraging citywide connectivity through Bus rapid Transit System, proposed Metro and the development of the SRFD. Further, with increased street connectivity, the public transportation coverage is expected to double from the existing 25%. The green cover will also be doubled from 20 % to 40%. -

3.2 Zoning and Development

3.2 Zoning and Development 3.2.1. Introduction ................................................................................................................ 14 3.2.2. Considerations for Proposals ...................................................................................... 14 3.2.3. Proposals and Recommendations .............................................................................. 16 Proposal 1: Densification of existing zoned areas ..................................................... 20 Proposal 2: Development of Central Business District (CBD) .................................... 21 Proposal 3: Densification along transit corridors through Transit Oriented Zone ..... 24 Proposal 4: Development around existing zoned areas to incentivize affordable housing ....................................................................................................................... 26 Proposal 5: Development in Growth Centers ............................................................ 27 Proposal 6: Development around village gamtals ..................................................... 30 Proposal 7: Introduction of Prime Agriculture Zone to preserve agriculture land .... 30 Proposal 8: Special Planned Area Development Zones (SPD) .................................... 31 3.2.4. Recommended Actions for implementation .............................................................. 33 3.2. Zoning and development 3.2.1. Introduction Today urban areas within AUDA limits are home of about 60 lakh people. As this number continues -

Monitoring Water Quality Fluctuation in the River Sabarmati

GUJARAT ENGINEERING RESEARCH INSTITUTE NARMADA, WATER RESOURCES, WATER SUPPLY & KALPASAR DEPARTMENT HYDROLOGY PROJECT (PDS FINAL REPORT) MONITORING WATER QUALITY FLUCTUATION IN THE RIVER SABARMATI 1 INSTITUTION AND INVESTIGATORS 1. NAME OF RESEARCH STATION GUJARAT ENGINEERING RESEARCH INSTITUTE AND ADRESS : Race Course, Vadodara-390 007 2. PROJECT DIRECTOR AND Shri. P.C. Vyas PRINCIPAL INVESTIGATOR : Chief Engineer and Director GERI, Race Course, Vadodara-390 007 3. CO-PROJECT DIRECTOR : Shri. R.H. Fefar Joint Director (I) GERI, Race Course, Vadodara-390 007 4. CO-INVESTIGATOR : 1. Smt. J.M. Shroff Research Officer North Gujarat Research Division GERI, Gandhinagar 2. Shri. A.H. Patel Assistant Research Officer Water Quality Testing Sub-Division, GERI, Gandhinagar 5. LABORATORY PERSONNEL : 1. Shri. B.V. Nagesh Junior Scientific Assistant Water Quality Testing Sub-Division GERI, Gandhinagar 2. Shri. H.R. Mulani Junior Scientific Assistant Water Quality Testing Sub-Division GERI, Gandhinagar 6. PROJECT TITLE : Monitoring Water Quality Fluctuation in River Sabarmati 7. PERIOD OF THE PROJECT : 3 Years 2 Abbreviations AMC Ahmedabad Municipal Corporation ASP Activated Sludge Process BOD Biochemical Oxygen Demand CETP Common Effluent Treatment Plant CGWB Central Ground Water Board CMIE Centre for Monitoring India’s Economy COD Chemical Oxygen Demand CPCB Central Pollution Control Board CWC Central Water Commission DO Dissolved Oxygen FC Fecal Coliform GoI Government of India GERI Gujarat Engineering Research Institute GIDC Gujarat Industrial -

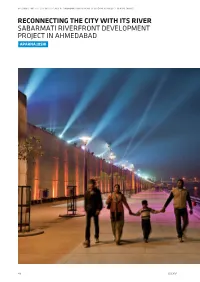

Reconnecting the City with Its River Sabarmati Riverfront Development Project in Ahmedabad Aparna Joshi

RECONNECTING THE CITY WITH ITS RIVER · SABARMATI RIVERFRONT DEVELOPMENT PROJECT IN AHMEDABAD RECONNECTING THE CITY WITH ITS RIVER SABARMATI RIVERFRONT DEVELOPMENT PROJECT IN AHMEDABAD APARNA JOSHI 48 ISOCARP APARNA JOSHI Ahmedabad, located in western India on the banks of the Sabarmati River, is the largest city in the State of Gujarat. The river has served as Ahmedabad’s lifeline for ages and has been an integral part of the rich his- tory of the city. It has been a major source for drinking water and informal recreational activities for the city. However, with rapid and haphazard urban growth by the end of twentieth century, the river became neg- lected, inaccessible and polluted. The city had turned its back towards the river. Riverfront development was a subject of interest to various city professionals since 1960s, but it was in 1997 that comprehensive planning was undertaken to transform Ahmedabad’s riverfront. Sabarmati Riverfront Development Project is a multi-dimensional project with several objectives. It aims to reclaim the private river-edge and turn it into a public asset thereby redefine the city’s relationship with its river by creating a thriving, people-centric network of parks, waterside promenades and civic facilities in the heart of the city. The project’s political objective is to provide a highly visible and robust urban renewal project around which the entire city can constructively rally. It is a first project of its kind in India. It is ongoing but already demonstrates that such projects can positively transform the city and be implemented in a fractious democracy like India, which is also why it has been much-talked about during the recent national elec- tions.