Evidence from Russia's Emancipation of the Serfs

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Washington, Bowdoin, and Franklin

WASH ING T 0 N, BOWDQIN, AND FRANKLIN, AS PORTRAYED IS 0CCASI0NAL AD L) RESSES. WashnQ ton JVitz.o nal Jtioimm ent Proposed heLght in clotted lines, 48.5 fi Completed, shown by dnrk lznes, 174 fi Stone Terrace, 25f* hzgh dLarneter 2OOfS WAS HIN G T 0 N, BOWDOIN, AND FRANKLIN, AS PORTRAYED IN OCCASIONAL ADDRESSES: BY vxi ROBERT C. WINTHROP. I WITH A FEW BRIE-F PIECES ON KINDRED TOPICS, ASD WITH NOTES AKD ILLUSTRATIONS. LITTLE, BROWN, AND COMPANY. 1876. 7 /' Entered according to Act of Congress, in the pear 1876, by LITTLE, BROW6, AND CONIPANY, In the Office of the Librarian of Congress, at Vashington. Cambridge : Press oj 70hWilson and Soti. PREFATORY NOTE. I ‘&VE so often, of late, been called on for copies of some of these productions, -no longer to be found in a separate or convenient form,-that I have ventured to think that they might prove an acceptable contribution to our Centennial Literature. They deal with two, certainly, of the greatest figures of the period we are engaged in commemorating; and BOWDOIN,I am persuaded, will be’ considered no un worthy associate of WASHINGTONand FRANKLINin such a publication. The Monument to Washington, to which the first pro duction relates, is still unfinished. It may be interesting to recall the fact that the Oration, on the laying of its corner-stone, was to have been delivered by JOHNQUINCY ADAMS. He died a few months before the occasion, and it was as Speaker of the House of Representatives of the United States, of which he had long been the most illus trious member, that I was called on to supply his place. -

202 Copyright © 2020 by Academic Publishing House Researcher S.R.O

European Journal of Contemporary Education, 2020, 9(1) Copyright © 2020 by Academic Publishing House Researcher s.r.o. All rights reserved. Published in the Slovak Republic European Journal of Contemporary Education E-ISSN 2305-6746 2020, 9(1): 202-211 DOI: 10.13187/ejced.2020.1.202 www.ejournal1.com WARNING! Article copyright. Copying, reproduction, distribution, republication (in whole or in part), or otherwise commercial use of the violation of the author(s) rights will be pursued on the basis of international legislation. Using the hyperlinks to the article is not considered a violation of copyright. The History of Education The Public Education System in Voronezh Governorate in the Period 1703–1917. Part 1 Aleksandr А. Cherkasov a , b , с , *, Sergei N. Bratanovskii d , e, Larisa A. Koroleva f a International Network Center for Fundamental and Applied Research, Washington, USA b Volgograd State University, Volgograd, Russian Federation с American Historical Association, Washington, USA d Plekhanov Russian University of Economics, Moscow, Russian Federation e Institute of State and Law of RAS, Moscow, Russian Federation f Penza State University of Architecture and Construction, Penza, Russian Federation Abstract This paper examines the public education system in Voronezh Governorate in the period 1703–1917. This part of the collection represents an attempt to reproduce a picture of how the region’s public education system developed between 1703 and 1861. In putting this work together, the authors drew upon a pool of statistical data published in Memorandum Books for Voronezh Governorate, reports by the Minister of Public Education, and Memorandum Books for certain educational institutions (e.g., the Voronezh Male Gymnasium). -

Peasants “On the Run”: State Control, Fugitives, Social and Geographic Mobility in Imperial Russia, 1649-1796

PEASANTS “ON THE RUN”: STATE CONTROL, FUGITIVES, SOCIAL AND GEOGRAPHIC MOBILITY IN IMPERIAL RUSSIA, 1649-1796 A Dissertation submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences of Georgetown University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History By Andrey Gornostaev, M.A. Washington, DC May 7, 2020 Copyright 2020 by Andrey Gornostaev All Rights Reserved ii PEASANTS “ON THE RUN”: STATE CONTROL, FUGITIVES, SOCIAL AND GEOGRAPHIC MOBILITY IN IMPERIAL RUSSIA, 1649-1796 Andrey Gornostaev, M.A. Thesis Advisers: James Collins, Ph.D. and Catherine Evtuhov, Ph.D. ABSTRACT This dissertation explores the issue of fugitive peasants by focusing primarily on the Volga-Urals region of Russia and situating it within the broader imperial population policy between 1649 and 1796. In the Law Code of 1649, Russia definitively bound peasants of all ranks to their official places of residence to facilitate tax collection and provide a workforce for the nobility serving in the army. In the ensuing century and a half, the government introduced new censuses, internal passports, and monetary fines; dispatched investigative commissions; and coerced provincial authorities and residents into surveilling and policing outsiders. Despite these legislative measures and enforcement mechanisms, many thousands of peasants left their localities in search of jobs, opportunities, and places to settle. While many fugitives toiled as barge haulers, factory workers, and agriculturalists, some turned to brigandage and river piracy. Others employed deception or forged passports to concoct fictitious identities, register themselves in villages and towns, and negotiate their status within the existing social structure. -

Second Serfdom and Wage Earners in European and Russian Thought from the Enlightenment to the Mid-Nineteenth Century

CHAPTER 1 SECOND SERFDOM AND WAGE EARNERS IN EUROPEAN AND RUSSIAN THOUGHT FROM THE ENLIGHTENMENT TO THE MID-NINETEENTH CENTURY The Eighteenth Century: Forced Labor between Reform and Revolution The invention of backwardness in Western economic and philosophical thought owes much to the attention given to Russia and Poland in the beginning of the eighteenth century.1 The definitions of backwardness and of labor—which is the main element of backwardness—lies at the nexus of three interrelated debates: over serfdom in Eastern European, slavery in the colonies, and guild reform in France. The connection between these three debates is what makes the definition of labor—and the distinction between free and forced labor—take on certain character- istics and not others. In the course of the eighteenth century, the work of slaves, serfs, and apprentices came to be viewed not just by ethical stan- dards, but increasingly by its efficiency. On that basis, hierarchies were justified, such as the “backwardness” of the colonies relative to the West, of Eastern relative to Western Europe, and of France relative to England. The chronology is striking. Criticisms of guilds, serfdom, and slavery all hardened during the 1750s; Montesquieu published The Spirit of the Laws in 1748, which was soon followed by the first volumes of the Ency- clopédie.2 In these works the serfdom of absolutist and medieval Europe was contrasted with the free labor of Enlightenment Europe. Abbé de Morelli took up these themes in 1755, condemning both ancient serf- dom and modern forms of slavery, in both the colonies and Russia. -

Alexander II and Gorbachev: the Doomed Reformers of Russia

University of Vermont UVM ScholarWorks UVM Honors College Senior Theses Undergraduate Theses 2017 Alexander II and Gorbachev: The Doomed Reformers of Russia Kate V. Lipman The University of Vermont Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.uvm.edu/hcoltheses Recommended Citation Lipman, Kate V., "Alexander II and Gorbachev: The Doomed Reformers of Russia" (2017). UVM Honors College Senior Theses. 158. https://scholarworks.uvm.edu/hcoltheses/158 This Honors College Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Undergraduate Theses at UVM ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in UVM Honors College Senior Theses by an authorized administrator of UVM ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 1 Alexander II and Gorbachev: The Doomed Reformers of Russia Kate V. Lipman Thesis Submitted for College Honors in History Advisor: Denise J. Youngblood The University of Vermont May 2017 2 Note on Sources: There is, surprisingly, little available in English on the reign of Alexander II, therefore I rely primarily on the works of W.E. Mosse, N.G.O Pereira, and the collection of works on Russia’s reform period edited by Ben Eklof. W.E. Mosse’s book Alexander II and the Modernization of Russia, a secondary source, provides in-depth descriptions of the problems facing Alexander II when he came into power, the process of his reforms, descriptions of the reforms, and some of the consequences of those reforms including his assassination in 1881. Similarly, N.G.O Pereira’s Tsar-Liberator: Alexander II of Russia 1818-1881 is a secondary source, describing some of his reforms, but focuses most specifically on the process of the emancipation of the serfs, the emancipation itself and the impact it had on the population. -

Jimmy Gentry

THE UNIVERSITY OF TENNESSEE KNOXVILLE AN INTERVIEW WITH JIMMY GENTRY FOR THE VETERANS ORAL HISTORY PROJECT CENTER FOR THE STUDY OF WAR AND SOCIETY DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY INTERVIEW BY G. KURT PIEHLER AND KELLY HAMMOND FRANKLIN, TENNESSEE JULY 22, 2000 TRANSCRIPT BY KELLY HAMMOND REVIEWED BY PATRICK LEVERTON GREGORY KUPSKY KURT PIEHLER: This begins an interview with Jimmy Gentry in Franklin, Tennessee on July 22, 2000 with Kurt Piehler and … KELLY HAMMOND: Kelly Hammond. PIEHLER: I guess I’d like to ask you a very basic question. When were you born, and where were you born? JIMMY GENTRY: I was born right here. Not in town; just out of Franklin, in what is now called Wyatt Hall. My family rented that house. I was there, but I don’t remember. (Laughs) So I was born right here. PIEHLER: What date were your born? GENTRY: Uh, November 28, 1924 or 5. Don’t ask me those questions like that. (Laughter) ’25, I believe, ‘cause I’ll soon be seventy-five. That must be right. PIEHLER: And you are native of Franklin. GENTRY: I really am. I have lived in Franklin, outside of Franklin, which is now in Franklin, and now I am back outside of Franklin. But Franklin is my home base, yes. PIEHLER: And could you maybe talk a little bit about your parents first? I guess, beginning with your father? GENTRY: Alright. My father originally came from North Carolina. Marshall, North Carolina, as I recall, near Asheville, and then he worked first for the railroad company for a short time. -

The Franklin's Tale

The Canterbury Tales by Geoffrey Chaucer 1/44 Contents Part One: The Prologue................................................................................3 Part Two: The Knight's Tale........................................................................ 8 Part Three: The Nun's Priest's Tale............................................................14 Part Four: The Pardoner's Tale...................................................................20 Part Five: The Wife of Bath's Tale.............................................................26 Part Six: The Franklin's Tale......................................................................32 Track 1: Part One Listening Exercise 4.................................................. 38 Track 2: Part Two Listening Exercise 5..................................................39 Track 3: Part Three Listening Exercise 4................................................40 Track 4: Part Four Listening Exercise 4................................................. 41 Track 5: Part Five Listening Exercise 5&6.............................................43 Track 6: Part Six Listening Exercise 4....................................................44 2/44 Part One: The Prologue In April, when the sweet showers① fallandfeedtherootsintheearth,the flowers begin to bloom②. The soft wind blows from the west and the young sun rises in the sky. The small birds sing in the green forests. Then people want to go on pilgrimages. from every part of England, they go to Canterbury to visit the tomb of Thomas Becket, the martyr③, who helped the sick. My name is Geoffrey Chaucer .People say that I am a poet but I am not really very important. I am just a story-teller. One day in spring, I was stayinginLondonattheTabardInn④. At night, a great crowd of people arrived at the inn, ready to go on a pilgrimage to Canterbury. I soon made friends with them and promised to join them. 'You must get up early,' they told me. 'We are leaving when the sun rises.' Before I begin my story, I will describe the pilgrims to you. -

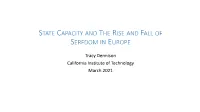

State Capacity and the Rise and Fall of Serfdom in Europe

STATE CAPACITY AND THE RISE AND FALL OF SERFDOM IN EUROPE Tracy Dennison California Institute of Technology March 2021 Motivations for This Project Two questions emerged from Voshchazhikovo study: 1) How do the estate- Summary: ➢Role of the state is key to understanding institutional context of serfdom ➢Serfdom is part of a weak state equilibrium; ruler must make concessions to other powerful actors to obtain services/revenues/cooperation. Serfdom is a constraint on fiscal aims of the crown. ➢In order to loosen this constraint, state has to be able to perform administrative functions that its noble agents perform in exchange for their privileges. ➢This happens gradually over 17th- 19th cc in Prussia (and earlier in much of western Europe). Decline of serfdom reflects underlying institutional reconfigurations. ➢In Russia serfdom is formally abolished, but the state still remains weak vis-à-vis other groups with limited options for surplus extraction. ➢Key difference: law - legal practices and processes - esp enforcement of property rights emerges as an important tool for states in western/central Europe but not in Russia ➢This suggestive finding has implications for our understanding of origins of ”inclusive”/”open access” institutions and emergence of strong central states Larger Political Economy of Serfdom Towns Merchants State Craft Guilds MerchantsNobles Peasants Even Larger Political Economy of Serfdom Towns Merchants State Craft Guilds MerchantsNobles CHURCH Peasants Institutional Framework of Serfdom Key Points (and Caveats): ➢State concedes privileges to different groups – all of which (including the state) are competing for surpluses - in exchange for: administration (tax collection, conscription), military service, revenue, loans, loyalty ➢These groups are not monolithic – nor is the state; there is internal conflict and there can be shifting alliances. -

Serfs and the Market: Second Serfdom and the East-West Goods Exchange, 1579-1857

Serfs and the Market: Second Serfdom and the East-West goods exchange, 1579-1857 Tom Raster1 Paris School of Economics [email protected] This version: June 2, 2019 Abstract Using novel shipment-level data on maritime trade between 1579 and 1856, this paper documents the evolution in grain exports from from Western to Eastern Europe and the rise of unfree labor in the former. Hypotheses first formulated more than 60 years ago, that export opportunities spurred labor coercion, motivate the exploration of this relationship. A new dataset of key labor legislation dates in the Baltic area captures de-jure unfree labor (e.g. serfdom or mobility bans). We also capture de-facto variation in coercion using existing data on coercion proxies (land holdings, serf manumission and/or wages) in Denmark, Prussia and Scania and novel household-level corvée data in Estonia. Our findings suggest that increases in grain prices and exports to the West happen, in many instances, concurrently with increases in de-jure and de-facto coercion in the East; thus, providing support for the hypothesis. Specifically, we observe that locations with better export potential see higher de-facto la- bor coercion; a finding that cannot be reconciled with existing models which predict less coercion in the proximity of cities due to outside options. We rationalize these findings in a new, open-economy labor coercion model that explains why foreign demand for grain is particularly likely to foster coercion. Our empirics may also be interpreted as evidence that Scania’s opening of the land market to peasants allowed them to benefit from trade and reduced labor coercion even in the absence of any coercion-constraining labor policies. -

Russian Serfdom, Emancipation, and Land Inequality: New Evidence

Russian Serfdom, Emancipation, and Land Inequality: New Evidence Steven Nafziger1 Department of Economics, Williams College May 2013 Note to Readers: This long descriptive paper is part of an even larger project - "Serfdom, Emancipation, and Economic Development in Tsarist Russia" - that is very much a work in progress. As such, some obvious extensions are left out. I apologize for any inconsistencies that remain. Abstract Serfdom is often viewed as a major institutional constraint on the economic development of Tsarist Russia, one that persisted well after emancipation occurred in 1861 through the ways that property rights were transferred to the peasantry. However, scholars have generally asserted this causal relationship with few facts in hand. This paper introduces a variety of newly collected data, covering European Russia at the district (uezd) level, to describe serfdom, emancipation, and the subsequent evolution of land holdings among the rural population into the 20th century. A series of simple empirical exercises describes several important ways that the institution of serfdom varied across European Russia; outlines how the emancipation reforms differentially affected the minority of privately owned serfs relative to the majority of other types of peasants; and connects these differences to long-run variation in land ownership, obligations, and inequality. The evidence explored in this paper constitutes the groundwork for considering the possible channels linking the demise of serfdom to Russia’s slow pace of economic growth prior to the Bolshevik Revolution. JEL Codes: N33, Keywords: Russia, economic history, serfdom, inequality, land reform, institutions 1 Tracy Dennison offered thoughtful questions at the onset of this project. Ivan Badinski, Cara Foley, Veranika Li, Aaron Seong, and Stefan Ward-Wheten provided wonderful research assistance. -

Franklin's Tale

FRANKLIN’S TALE The Portrait, Prologue and Tale of the Franklin FRANKLIN’S TALE 1 The portrait of the Franklin from the General Prologue where he is shown as a generous man who enjoys the good things of life. He travels in the company of a rich attorney, the Man of Law A FRANKLIN was in his company. rich landowner White was his beard as is the daisy. Of his complexïon he was sanguine.1 ruddy & cheerful Well loved he by the morrow a sop in wine. in the a.m. 335 To liv•n in delight was ever his won, custom For he was Epicurus's own son That held opinïon that plain delight total pleasure Was very felicity perfite. 2 truly perfect happiness A householder and that a great was he; 340 Saint Julian he was in his country.3 His bread, his ale, was always after one. of one kind i.e. good A better envin•d man was never none. with better wine cellar Withouten bak•d meat was never his house food Of fish and flesh, and that so plenteous 345 It snow•d in his house of meat and drink food Of all• dainties that men could bethink. After the sundry seasons of the year according to So chang•d he his meat and his supper. Full many a fat partridge had he in mew pen 350 And many a bream and many a luce in stew. fish / in pond Woe was his cook but if his sauc• were Poignant and sharp, and ready all his gear.4 tangy His table dormant in his hall alway set / always Stood ready covered all the long• day. -

Serfdom and State Power in Imperial Russia

Roger Bartlett Serfdom and State Power in Imperial Russia The institution of serfdom has been a central and much debated feature of early modern Russian history: it has sometimes been described as Russia’s ‘peculiar institution’, as central to the Russian experience as black slavery has been to the American.1 It is striking, however, that the rise and dominance of serfdom within Muscovite/Russian society coincided closely in historical terms with the rise to European eminence and power of the Muscovite state and Russian Empire. The subjection of the peasantry to its landlord masters was finally institutionalized in 1649, at a time when for most of the rest of Europe Muscovy was a little-known and peripheral state, in John Milton’s words, ‘the most northern Region of Europe reputed civil’.2 When Peter I proclaimed Russia an empire, in 1721, it had displaced Sweden to become the leading state of Northern Europe; one hundred years later Russia was the premier European land power. Its loss of international status after the Crimean War in 1856 helped to precipitate the abolition of serfdom (1861); but the ‘Great Reforms’ of the 1860s did not enable it to regain the international position achieved after the Napoleonic Wars. Thus the period of history from the mid-seventeenth to mid-nineteenth centuries, when serfdom became a securely entrenched legal and economic institution, was also the period in which Russia — the Muscovite state and Russian Empire — became relatively more powerful than at any other time in its history before 1945. This article seeks to examine some of the features of serfdom in Russia, to look briefly at its place in the structure and dynamics of Russian society, and to investigate the relationship between the establish- ment of serfdom in practice and the success of Russian govern- ments both in domestic affairs and on the international stage.