British Journal for Military History

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

![1 Armoured Division (1940)]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/0098/1-armoured-division-1940-130098.webp)

1 Armoured Division (1940)]

7 September 2020 [1 ARMOURED DIVISION (1940)] st 1 Armoured Division (1) Headquarters, 1st Armoured Division 2nd Armoured Brigade (2) Headquarters, 2nd Armoured Brigade & Signal Section The Queen’s Bays (2nd Dragoon Guards) 9th Queen’s Royal Lancers 10th Royal Hussars (Prince of Wales’s Own) 3rd Armoured Brigade (3) Headquarters, 3rd Armoured Brigade & Signal Section 2nd Royal Tank Regiment 3rd Royal Tank Regiment (4) 5th Royal Tank Regiment 1st Support Group (5) Headquarters, 1st Support Group & Signal Section 2nd Bn. The King’s Royal Rifles Corps 1st Bn. The Rifle Brigade (Prince Consort’s Own) 1st Regiment, Royal Horse Artillery (H.Q., A/E & B/O Batteries, Royal Horse Artillery) 2nd Regiment, Royal Horse Artillery (H.Q., L/N & H/I Batteries, Royal Horse Artillery) Divisional Troops 1st Field Squadron, Royal Engineers 1st Field Park Troop, Royal Engineers 1st Armoured Divisional Signals, (1st County of London Yeomanry (Middlesex, Duke of Cambridge’s Hussars)), Royal Corps of Signals ©www.BritishMilitaryH istory.co.uk Page 1 7 September 2020 [1 ARMOURED DIVISION (1940)] NOTES: 1. A pre-war Regular Army formation formerly known as The Mobile Division. The divisional headquarters were based at Priory Lodge near Andover, within Southern Command. This was the only armoured division in the British Army at the outbreak of the Second World War. The division remained in the U.K. training and equipping until leaving for France on 14 May 1940. Initial elements of the 1st Armoured Division began landing at Le Havre on 15 May, being sent to a location south of Rouen to concentrate and prepare for action. -

Violence, Warfare and Politics in Colonial Burma(<Special Issue

State Formation in the Shadow of the Raj: Violence, Warfare Title and Politics in Colonial Burma(<Special Issue>State Formation in Comparative Perspectives) Author(s) Callahan, Mary P. Citation 東南アジア研究 (2002), 39(4): 513-536 Issue Date 2002-03 URL http://hdl.handle.net/2433/53713 Right Type Departmental Bulletin Paper Textversion publisher Kyoto University Southeast Asian Studies, Vol. 39, No. 4, March 2002 State Formation in the Shadow of the Raj: Violence, Warfare and Politics in Colonial Burma* Mary P. CALLAHAN** Normally, society is organized for life; the object of Leviathan was to organise it for production. J.S. Furnivall [1939: 124] Abstract This article examines the construction of the colonial security apparatus in Burma, within the broader British colonial project in eastern Asia. During the colonial period, the state in Burma was built by default, as no one in London or India ever mapped out a strategy for establishing governance in this outpost. Instead of sending in legal, commercial or police experts to establish law and order—the preconditions of the all-important commerce— Britain sent the Indian Army, which faced an intensity and landscape of guerilla resistance never anticipated. Early forays into the establishment of law and order increasingly became based on conceptions of the population as enemies to be pacified, rather than subjects to be incorporated into or even ignored by the newly defined political entity. The character of armed administration in colonial Burma had a disproportionate impact on how that popula- tion came to be regarded, treated, legalized and made into subjects of the Raj. -

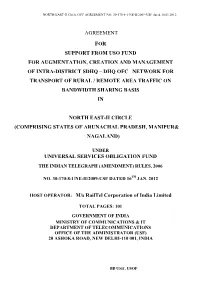

Dhq Ofc Network for Transport of Rural / Remote Area Traffic on Bandwidth Sharing Basis In

NORTH EAST-II Circle OFC AGREEMENT NO. 30-170-8-1-NE-II/2009-USF dated 16.01.2012 AGREEMENT FOR SUPPORT FROM USO FUND FOR AUGMENTATION, CREATION AND MANAGEMENT OF INTRA-DISTRICT SDHQ – DHQ OFC NETWORK FOR TRANSPORT OF RURAL / REMOTE AREA TRAFFIC ON BANDWIDTH SHARING BASIS IN NORTH EAST-II CIRCLE (COMPRISING STATES OF ARUNACHAL PRADESH, MANIPUR& NAGALAND) UNDER UNIVERSAL SERVICES OBLIGATION FUND THE INDIAN TELEGRAPH (AMENDMENT) RULES, 2006 NO. 30-170-8-1/NE-II/2009-USF DATED 16TH JAN, 2012 HOST OPERATOR: M/s RailTel Corporation of India Limited TOTAL PAGES: 101 GOVERNMENT OF INDIA MINISTRY OF COMMUNICATIONS & IT DEPARTMENT OF TELECOMMUNICATIONS OFFICE OF THE ADMINISTRATOR (USF) 20 ASHOKA ROAD, NEW DELHI-110 001, INDIA BB UNIT, USOF NORTH EAST-II OFC AGREEMENT No. 30-170-8-1/NE-II/2009-USF dated 16 .01.2012 AGREEMENT FOR SUPPORT FROM USO FUND FOR AUGMENTATION, CREATION AND MANAGEMENT OF INTRA-DISTRICT SDHQ – DHQ OFC NETWORK FOR TRANSPORT OF RURAL / REMOTE AREA TRAFFIC ON BANDWIDTH SHARING BASIS IN NORTH EAST-II CIRCLE(COMPRISING STATES OF ARUNACHAL PRADESH,MANIPUR& NAGALAND This Agreement, for and on behalf of the President of India, is entered into on the 16TH day of January 2012 by and between the Administrator, Universal Service Obligation Fund, Department of Telecommunications, acting through Shri Arun Agarwal, Director (BB) USOF, Department of Telecommunications (DoT), Sanchar Bhawan, 20, Ashoka Road, New Delhi – 110 001 (hereinafter called the Administrator) of the First Party. And M/s RailTel Corporation of India Limited, a company registered under the Companies Act 1956, having its registered office at 10th Floor, Bank of Baroda Building, 16 Sansad Marg New Delhi, acting through Shri Anshul Gupta, Chief General Manager/Marketing, the authorized signatory (hereinafter called the Host Operator which expression shall, unless repugnant to the context, includes its successor in business, administrators, liquidators and assigns or legal representatives) of the Second Party. -

Copyright by John Michael Meyer 2020

Copyright by John Michael Meyer 2020 The Dissertation Committee for John Michael Meyer Certifies that this is the approved version of the following Dissertation. One Way to Live: Orde Wingate and the Adoption of ‘Special Forces’ Tactics and Strategies (1903-1944) Committee: Ami Pedahzur, Supervisor Zoltan D. Barany David M. Buss William Roger Louis Thomas G. Palaima Paul B. Woodruff One Way to Live: Orde Wingate and the Adoption of ‘Special Forces’ Tactics and Strategies (1903-1944) by John Michael Meyer Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Texas at Austin May 2020 Dedication To Ami Pedahzur and Wm. Roger Louis who guided me on this endeavor from start to finish and To Lorna Paterson Wingate Smith. Acknowledgements Ami Pedahzur and Wm. Roger Louis have helped me immeasurably throughout my time at the University of Texas, and I wish that everyone could benefit from teachers so rigorous and open minded. I will never forget the compassion and strength that they demonstrated over the course of this project. Zoltan Barany developed my skills as a teacher, and provided a thoughtful reading of my first peer-reviewed article. David M. Buss kept an open mind when I approached him about this interdisciplinary project, and has remained a model of patience while I worked towards its completion. My work with Tom Palaima and Paul Woodruff began with collaboration, and then moved to friendship. Inevitably, I became their student, though they had been teaching me all along. -

TRANSFORMING the BRITISH ARMY an Update

TRANSFORMING THE BRITISH ARMY An Update © Crown copyright July 2013 Images Army Picture Desk, Army Headquarters Designed by Design Studio ADR002930 | TRANSFORMING THE BRITISH ARMY 2013 TRANSFORMING THE BRITISH ARMY 2013 | 1 Contents Foreword 1 Army 2020 Background 2 The Army 2020 Design 3 Formation Basing and Names 4 The Reaction Force 6 The Adaptable Force 8 Force Troops Command 10 Transition to new Structures 14 Training 15 Personnel 18 Defence Engagement 21 Firm Base 22 Support to Homeland Resilience 23 Equipment 24 Reserves 26 Army Communication Strategic Themes 28 | TRANSFORMING THE BRITISH ARMY 2013 TRANSFORMING THE BRITISH ARMY 2013 | 1 Foreword General Sir Peter Wall GCB CBE ADC Gen Chief of the General Staff We have made significant progress in refining the detail of Army 2020 since it was announced in July 2012. It is worth taking stock of what has been achieved so far, and ensuring that our direction of travel continues to be understood by the Army. This comprehensive update achieves this purpose well and should be read widely. I wish to highlight four particular points: • Our success in establishing Defence Engagement as a core Defence output. Not only will this enable us to make a crucial contribution to conflict prevention, but it will enhance our contingent capability by developing our understanding. It will also give the Adaptable Force a challenging focus in addition to enduring operations and homeland resilience. • We must be clear that our capacity to influence overseas is founded upon our credibility as a war-fighting Army, capable of projecting force anywhere in the world. -

Rohingya Crisis: an Analysis Through a Theoretical Perspective

International Relations and Diplomacy, July 2020, Vol. 8, No. 07, 321-331 doi: 10.17265/2328-2134/2020.07.004 D D AV I D PUBLISHING Rohingya Crisis: An Analysis Through a Theoretical Perspective Sheila Rai, Preeti Sharma St. Xavier’s College, Jaipur, India The large scale exodus of Rohingyas to Bangladesh, Indonesia, Malaysia, and Thailand as a consequence of relentless persecution by the Myanmar state has gained worldwide attention. UN Secretary General, Guterres called it “ethnic cleansing” and the “humanitarian situation as catastrophic”. This catastrophic situation can be traced back to the systemic and structural violence perpetrated by the state and the society wherein the Burmans and Buddhism are taken as the central rallying force of the narrative of the nation-state. This paper tries to analyze the Rohingya discourse situating it in the theoretical precepts of securitization, structural violence, and ethnic identity. The historical antecedents and particular circumstances and happenings were construed selectively and systematically to highlight the ethnic, racial, cultural, and linguistic identity of Rohingyas to exclude them from the “national imagination” of the state. This culture of pervasive prejudice prevailing in Myanmar finds manifestation in the legal provisions whereby certain peripheral minorities including Rohingyas have been denied basic civil and political rights. This legal-juridical disjunction to seal the historical ethnic divide has institutionalized and structuralized the inherent prejudice leveraging the religious-cultural hegemony. The newly instated democratic form of government, by its very virtue of the call of the majority, has also been contributed to reinforce this schism. The armed attacks by ARSA has provided the tangible spur to the already nuanced systemic violence in Myanmar and the Rohingyas are caught in a vicious cycle of politicization of ethnic identity, structural violence, and securitization. -

The Chittagonians in Colonial Arakan: Seasonal and Settlement Migrations Jacques Leider

The Chittagonians in Colonial Arakan: Seasonal and Settlement Migrations Jacques Leider To cite this version: Jacques Leider. The Chittagonians in Colonial Arakan: Seasonal and Settlement Migrations. Morten Bergsmo; Wolfgang Kaleck; Kyaw Yin Hlaing. Colonial Wrongs and Access to International Law, 40, Torkel Opsahl Academic EPublisher, pp.177-227, 2020, Publication Series, 978-82-8348-134-1. hal- 02997366 HAL Id: hal-02997366 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-02997366 Submitted on 10 Nov 2020 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Public Domain Colonial Wrongs and Access to International Law Morten Bergsmo, Wolfgang Kaleck and Kyaw Yin Hlaing (editors) E-Offprint: Jacques P. Leider, “The Chittagonians in Colonial Arakan: Seasonal and Settlement Migrations”, in Morten Bergsmo, Wolfgang Kaleck and Kyaw Yin Hlaing (editors), Colonial Wrongs and Access to International Law, Torkel Opsahl Academic EPub- lisher, Brussels, 2020 (ISBNs: 978-82-8348-133-4 (print) and 978-82-8348-134-1 (e- book)). This publication was first published on 9 November 2020. TOAEP publications may be openly accessed and downloaded through the web site https://www.toaep.org which uses Persistent URLs (PURLs) for all publications it makes available. -

State Formation in the Shadow of the Raj: Violence, Warfare and Politics in Colonial Burma*

Southeast Asian Studies, Vol. 39, No. 4, March 2002 State Formation in the Shadow of the Raj: Violence, Warfare and Politics in Colonial Burma* Mary P. CALLAHAN** Normally, society is organized for life; the object of Leviathan was to organise it for production. J.S. Furnivall [1939: 124] Abstract This article examines the construction of the colonial security apparatus in Burma, within the broader British colonial project in eastern Asia. During the colonial period, the state in Burma was built by default, as no one in London or India ever mapped out a strategy for establishing governance in this outpost. Instead of sending in legal, commercial or police experts to establish law and order—the preconditions of the all-important commerce— Britain sent the Indian Army, which faced an intensity and landscape of guerilla resistance never anticipated. Early forays into the establishment of law and order increasingly became based on conceptions of the population as enemies to be pacified, rather than subjects to be incorporated into or even ignored by the newly defined political entity. The character of armed administration in colonial Burma had a disproportionate impact on how that popula- tion came to be regarded, treated, legalized and made into subjects of the Raj. Administra- tive simplifications along territorial and racial lines resulted in political, economic, and social boundaries that continue to divide the country today. Bureaucratic and security mech- anisms politicized violence along territorial and racial lines, creating “two Burmas” in the administrative and security arms of the state. Despite the “laissez-faire” proclamations of colonial state officials in Burma, this geographically and functionally limited state nonethe- less established durable administrative structures that precluded any significant integration throughout the territory for a century to come. -

Migration from Bengal to Arakan During British Rule 1826–1948 Derek Tonkin

Occasional Paper Series Migration from Bengal to Arakan during British Rule 1826–1948 Derek Tonkin Migration from Bengal to Arakan during British Rule 1826–1948 Derek Tonkin 2019 Torkel Opsahl Academic EPublisher Brussels This and other publications in TOAEP’s Occasional Paper Series may be openly accessed and downloaded through the web site http://toaep.org, which uses Persistent URLs for all publications it makes available (such PURLs will not be changed). This publication was first published on 6 December 2019. © Torkel Opsahl Academic EPublisher, 2019 All rights are reserved. You may read, print or download this publication or any part of it from http://www.toaep.org/ for personal use, but you may not in any way charge for its use by others, directly or by reproducing it, storing it in a retrieval system, transmitting it, or utilising it in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, in whole or in part, without the prior permis- sion in writing of the copyright holder. Enquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the copyright holder. You must not circulate this publication in any other cover and you must impose the same condition on any ac- quirer. You must not make this publication or any part of it available on the Internet by any other URL than that on http://www.toaep.org/, without permission of the publisher. ISBN: 978-82-8348-150-1. TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. Introduction .............................................................................................. 2 2. Setting the Scene: The 1911, 1921 and 1931 Censuses of British Burma ............................ -

Bibliographic Guide to Further Reading

BIBLIOGRAPHIC GUIDE TO FURTHER READING The historical, memoir, travel, and technical literature on Ethiopia is immense and continually growing. A complete bibliography would require a very thick volume. Included below are most of the major books cited in the text. Journal articles, pamphlets and monographs are not included. Many worthwhile books from my own collection not specifically referenced in the footnotes have been added. Books in languages other than English, German, French, Italian and Portu guese are not listed. Among the most valuable sources for research on Ethiopia are the proceedings of the triennial International Ethiopian Studies Conferences (IESC), the most recent of which were held in East Lansing, Michigan in September 1994 and in Kyoto,Japan in Decem ber 1997. The former produced 2,372 pages of papers published as New Trends in Ethiopian Studies (2 vols. Red Sea Press, No. 1994). The latter resulted in 2,345 pp. of papers published as Ethiopia in Broader Perspective (Shokado, Kyoto, 1997, 3vols). The 14th IESC is scheduled to take place in Addis Ababa in November 2000. Many other volumes of conference proceedings have been published in Ethiopia and elsewhere during the past three decades. With only a few except ions, these have not been listed below. HISTORY AND CULTURE, GENERAL Berhanou Abebe, Historie de lithiopie d'Axoum ala revolution, Maison neuve et Larose, Paris, 1998. E. A. Wallis Budge, History ofEthiopia: Nubia and Abyssinia, Methuen, London, 192R David Buxton, The Abyssinians, Thames & Hudson, London, 1970. Franz Amadeus Dombrowski, Ethiopia sAccess to the Sea, EJ. Brill, Leiden, 1985. Jean Doresse, Ethiopia, Elee, London, 1959. -

CHAPTER X IT Is Now Time to Lift the Veil That Hid from the Arriving

CHAPTER X “THE TRUTH ABOUT THE ‘FIFTH’ ARMY”1 IT is now time to lift the veil that hid from the arriving reinforcements the chain of events that had produced the situations into which they were flung. It may be taken as an axiom that, when an army is in the grip of a desperate struggle, any one moving in its rear tends to be unduly impressed with the disorganisation, the straggling, the anxiety of the staffs, and other inevitable incidents of such a battle; he sees the exhausted and also the less stubborn fragments of the force, and is impressed with their statements, while the more virile and faithful element, mainly fighting out in front, ignorant or heedless of all such weakness in rear, is largely beyond his view. It is undeniable that during and after their race to the Aniiens front the Australian divisions were witnesses of many incidents that impressed them with a lack of virility in a certain proportion of the British troops. Rumours depre- ciating the resistance offered by parts of the Fifth Army were widespread not only throughout the remainder of the British Army, but among the French population, and were even current in England. The Australian troops were the ctief reinforcement sent to that army by the British command in the later stage of the retirement, and eventually occupied the whole of its remaining front as well as part of the Third Army’s. The Australian soldier was not an unfair critic. If the Performance of a neighbouring unit excited his admiration, no one was so enthusiastic and outspoken in his praise; but, where performance fell short of its expectations, it was quite useless to attempt to gloss over to him such failure. -

Manipur State Information Technology Society

MANIPUR STATE INFORMATION TECHNOLOGY SOCIETY (A Government of Manipur Undertaking) 4th Floor, Western Block, New Secretariat, Imphal – 795001 www.msits.gov.in; Email: [email protected] Phone: 0385-24476877 District wise Status of Common Service Centres (As on 25th March, 2013) District: Ukhrul Total No. of CSCs : 33 VSAT Solar Power Sl. CSC Location & VLE Contact District BLOCK CSC Name Name of VLE Installation pack status No Address Number Status 1 Ukhrul Ukhrul CSC-Hundung Hundung K.Y.S Yangmi 9612005006 Installed Installed 2 Ukhrul Chingai CSC-Kalhang Kalhang R.S. Michael (Aphung) 9612765614 / Pending Installed 9612130987 3 Ukhrul Ukhrul CSC-Nungshong Nungshong Khullen Ignitius Yaoreiwung 9862883374 Pending Installed Khullen Chithang 4 Ukhrul Ukhrul CSC-Shangkai Shangkai Chongam Haokip 9612696292 Installed Installed 5 Ukhrul Ukhrul CSC-New Cannon New Cannon ZS Somila 9862826487 / Installed Installed 9862979109 6 Ukhrul Ukhrul CSC-Jessami Jessami Village Nipekhwe Lohe 9862835841 Pending Installed 7 Ukhrul Ukhrul CSC-Teinem Teinem Mashangam Raleng 8730963043 Pending Installed 8 Ukhrul Ukhrul CSC-Seikhor Seikhor L.A. Pamreiphi 9436243204 / Pending Installed 857855919 / 8731929981 9 Ukhrul Chingai CSC-Chingjaroi Chingjaroi Khullen Joyson Tamang 9862992294 Pending Installed Khullen 10 Ukhrul Ukhrul CSC-Litan Litan JS. Aring 9612937524 / Installed Installed 8974425854 / 9436042452 11 Ukhrul Ukhrul CSC-Shangshak Shangshak khullen R.S. Ngaranmi 9862069769 / Pending Installed T.D.Block Khullen 9436086067 / 9862701697 12 Ukhrul Ukhrul CSC-Lambui Lambui L. Seth 9612489203 / Installed Installed T.D.Block 8974459592 / 9862038398 13 Ukhrul Kasom Khullen CSC-Kasom Kasom Khullen Shanglai Thangmeichui 9862760611 / Not approved for Installed T.D.Block Khullen 9612320431 VSAT 14 Ukhrul Kasom Khullen CSC-Khamlang Khamlang N.