BUILDING BETTER BAILOUTS: the CASE for a LONG-TERM INVESTMENT APPROACH Jeffrey Manns Abstract the Article Seeks to Fill a Crucia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Merging the SEC and CFTC - a Clash of Cultures

Florida International University College of Law eCollections Faculty Publications Faculty Scholarship 2009 Merging the SEC and CFTC - A Clash of Cultures Jerry W. Markham Florida International University College of Law Follow this and additional works at: https://ecollections.law.fiu.edu/faculty_publications Part of the Banking and Finance Law Commons Recommended Citation Jerry W. Markham, Merging the SEC and CFTC - A Clash of Cultures, 78 U. Cin. L. Rev. 537, 612 (2009). This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Scholarship at eCollections. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of eCollections. For more information, please contact [email protected]. +(,121/,1( Citation: Jerry W. Markham, Merging the SEC and CFTC - A Clash of Cultures, 78 U. Cin. L. Rev. 537 (2009) Provided by: FIU College of Law Content downloaded/printed from HeinOnline Tue May 1 10:36:12 2018 -- Your use of this HeinOnline PDF indicates your acceptance of HeinOnline's Terms and Conditions of the license agreement available at https://heinonline.org/HOL/License -- The search text of this PDF is generated from uncorrected OCR text. -- To obtain permission to use this article beyond the scope of your HeinOnline license, please use: Copyright Information Use QR Code reader to send PDF to your smartphone or tablet device MERGING THE SEC AND CFTC-A CLASH OF CULTURES Jerry W. Markham* I. INTRODUCTION The massive subprime losses at Citigroup, UBS, Bank of America, Wachovia, Washington Mutual, and other banks astounded the financial world. Equally shocking were the failures of Lehman Brothers, Merrill Lynch, and Bear Steams. -

One Cheer for Credit Rating Agencies: How the Mark-To-Market Accounting Debate Highlights the Case for Rating-Dependent Capital Regulation

South Carolina Law Review Volume 60 Issue 3 Article 8 Spring 2009 One Cheer for Credit Rating Agencies: How the Mark-to-Market Accounting Debate Highlights the Case for Rating-Dependent Capital Regulation John P. Hunt Berkeley Center for Law Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/sclr Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation John Patrick Hunt, One Cheer for Credit Rating Agencies: How the Mark-to-Market Accounting Debate Highlights the Case for Rating-Dependent Capital Regulation, 60 S. C. L. Rev. 749 (2009). This Symposium Paper is brought to you by the Law Reviews and Journals at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in South Carolina Law Review by an authorized editor of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Hunt: One Cheer for Credit Rating Agencies: How the Mark-to-Market Acco ONE CHEER FOR CREDIT RATING AGENCIES: How THE MARK-TO-MARKET ACCOUNTING DEBATE HIGHLIGHTS THE CASE FOR RATING-DEPENDENT CAPITAL REGULATION JOHN PATRICK HUNT INJ. TRO D UCTIO N .......................................................................................... 750 11. MARK-TO-MARKET FINANCIAL ACCOUNTING INTHE 2007-2008 C RISIS .......................................................................... 752 A. Fair Value, or Mark-to-Market FinancialAccounting Rules ............ 752 B. The Attack on Mark-to-Market Accounting and Its Effects ................ 757 C. Mark-to-Market Accounting Critics Have Failedto M ake Their Case ....................................................... 759 1. Accounting Rules Generally Do Not "Require" M arking to M arket .................................................... 759 2. Market Marks GenerallyAre Not Binding and Do Not Require ForcedSelling ............................................ 760 3. Accounting Losses Did Not Cause Any of the Major Firm Failures in the Crisis............................. -

Cumulative Or Discrete Numbers: Should Bloomberg Measure the Bailout? Teaching Note

Cumulative or Discrete Numbers: Should Bloomberg Measure the Bailout? Teaching Note Case Summary Financial reporting presents formidable challenges for journalists. To begin with, the journalist must have a solid grasp of the mathematically complex products and practices of modern finance, as well as an understanding of the greater economic environment at the national and international level. Furthermore, the stories—which by nature are full of numbers—must be palatable for readers. Thus it often falls on journalists to decide how best to present the figures so that the story is not only factually correct but also easy for readers to digest. This case focuses on Bloomberg News as it covered one such story: the Federal Reserve’s bailout of major banks during the financial crisis of 2007-10. As big banks struggled to keep themselves afloat after incurring huge losses in bundled subprime mortgages, the Federal Reserve created several emergency lending programs for banks. However, key details such as borrowers’ names, amount borrowed and collateral were not disclosed. Such lack of transparency prompted reporters at Bloomberg News to file a Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) request in May 2008. The Fed stonewalled Bloomberg’s FOIA request, claiming that such information could undermine the effectiveness of the emergency program, because the market could interpret the loans as signs of grave financial trouble. Undaunted, Bloomberg took the issue to court in November 2008 and prevailed. Moreover, the 2010 Dodd-Frank Act on financial oversight also required that the Fed release more information about its lending. This confluence of circumstances led the Fed in late 2010 to release information sought by Bloomberg and other media outlets. -

Super Regulators?

Brooklyn Journal of International Law Volume 28 Issue 2 SYMPOSIUM: Do Financial Supermarkets Need Article 4 Super Regulators? 2003 Super Regulator: A Comparative Analysis of Securities and Derivatives Regulation in the United States, the United Kingdom, and Japan Jerry W. Markham Follow this and additional works at: https://brooklynworks.brooklaw.edu/bjil Recommended Citation Jerry W. Markham, Super Regulator: A Comparative Analysis of Securities and Derivatives Regulation in the United States, the United Kingdom, and Japan, 28 Brook. J. Int'l L. (2003). Available at: https://brooklynworks.brooklaw.edu/bjil/vol28/iss2/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at BrooklynWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Brooklyn Journal of International Law by an authorized editor of BrooklynWorks. File: Markham Base Macro Final.doc Created on: 3/20/2003 5:05 PM Last Printed: 4/28/2003 11:3 1 AM SUPER REGULATOR: A COMPARATIVE ANALYSIS OF SECURITIES AND DERIVATIVES REGULATION IN THE UNITED STATES, THE UNITED KINGDOM, AND JAPAN Jerry W. Markham* I. INTRODUCTION he value of competition among regulators has been the T subject of debate in the United States (“U.S.”) for some time.1 On the one hand, its advocates contend that com- peting regulatory bodies will not only govern less, but also more efficiently.2 Proponents of centralized regulation, on the other hand, argue that ove rlapping regulation is costly, inefficient, and allows exploitation and abuses along regulatory seams.3 In supporting their arguments, however, both sides of this debate rely largely on intuitive arguments or anecdotal evidence. -

May/June 2019

www.newsandtech.com www.newsandtech.com May/June 2019 The premier resource for insight, analysis and technology integration in newspaper and hybrid operations and production. East Coast publisher breathing new life into local advertising u BY TARA MCMEEKIN CONTRIBUTING WRITER For many local newspapers, social media — namely Facebook — Extending advertisers’ reach plays a major role. However, the social media giant is continually “We were looking for ways to jump on the Facebook bandwagon and changing its algorithms — often to the disadvantage of local advertis- help our advertisers extend their reach,” Jeanne Straus, CEO of Straus ers — and controlling which businesses its users see. This has made it News, told News & Tech. “As Facebook has changed its algorithms to increasingly difficult for newspapers and their advertisers to reap all businesses’ disadvantage, we thought Innocode could help.” the potential benefits from the platform. Established in 2011 in Norway, Innocode provides digital products Straus News, which publishes 17 local weekly newspapers in New aimed at helping newspapers secure their positions as community York, New Jersey and Pennsylvania, recently decided it was time to hubs and develop new sources of revenue through social media. do something to enable advertisers to gain better market share and Straus said she first discovered Innocode and the Local Offers prod- visibility on Facebook. uct that underpins the publisher’s ShopLocal program at an annual To accomplish that goal, the publisher launched its ShopLocal -

How Should Bloomberg Measure the Bailout?

CSJ----13--- -0051.0 Cumulative or Discrete Numbers: How Should Bloomberg Measure the Bailout? From summer 2007 to June 2009, US financial markets flirted with disaster. The housing market had collapsed and, because many major financial institutions were heavily invested in mortgages, they lost hundreds of billions of dollars. The economy went into recession in December 2007 and contracted a full 5.1 percent in 18 months. Millions lost their jobs; other millions lost their homes. At the height of the crisis, experts and ordinary citizens alike wondered whether the nation’s banking system would survive. The US Federal Reserve System, the nation’s central bank, stepped in with a variety of programs to stabilize the banks. While the public knew that the “Fed,” as it was called, was taking action, the agency released few details about individual transactions. At Bloomberg News, investigative reporter Mark Pittman became convinced that banks were using Fed loans to disguise financial weakness. In May 2008, he filed a Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) request with the Fed to learn how much it had loaned each bank, and on what terms.1 When after six months the Fed failed to respond, Bloomberg L.P. (the parent company) in November 2008 filed a lawsuit to obtain detailed records about its massive lending activities. Over the next two years, the two parties fought a legal battle. Bloomberg won at both the district and appeals court levels, but the Fed or its proxy continued to appeal the decision until, in March 2011, the Supreme Court refused to hear the case. -

Downloads, Or Printer WE’RE RESPONSIBLE for WHAT WE PRINT

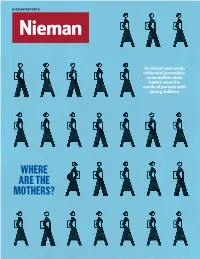

NIEMAN REPORTS To attract and retain millennial journalists, news outlets must better meet the needs of parents with young children WHERE ARE THE MOTHERS? Contributors The Nieman Foundation for Journalism at Harvard University Katherine Goldstein www.niemanreports.org (page 24), a 2017 Nieman Fellow, is a digital journalist and consultant focusing on issues of women and work. She leads workshops, coaches, and teaches a course at the Harvard Extension School on how to develop a journalism career. Previously, she worked publisher Ann Marie Lipinski as the editor of vanityfair.com, the director of traffic and social media strategy at Slate, and as the green editor at The Huffington editor Post. In addition to her editorial, strategy, and managerial roles, James Geary she has covered topics ranging from the Copenhagen climate talks senior editor to the first gay wedding on a military base. She lives in Brooklyn, Jan Gardner New York with her husband and son. editorial assistant Eryn M. Carlson Diego Marcano (page 8) is a Venezuelan journalist now attending staff assistant Boston University. Previously, he was Lesley Harkins based in Colombia as a reporter at design Prodavinci, where he covered policy, Pentagram international affairs, and technology. editorial offices One Francis Avenue, Cambridge, Laura Beltrán Villamizar (page 12), MA 02138-2098, 617-496-6308, an independent photography editor and [email protected] writer, is the founder of Native Agency, a platform dedicated to the promotion and Copyright 2017 by the President and Fellows of Harvard College. development of visual journalists from Periodicals postage paid at underrepresented regions. Boston, Massachusetts and additional entries Jon Marcus (pages 14 and 42 ) is higher- education editor at The Hechinger Report, subscriptions/business a nonprofit news organization based at 617-496-6299, [email protected] Columbia University. -

FSFP Ltr to NY AG to Revoke Trump Org Corp Charter 2-15-2017 Final

The Honorable Eric T. Schneiderman Attorney General of the State of New York The Capitol Albany, New York 12224 Re: Request to Initiate Investigation Whether to Dissolve and Revoke Corporate Charter of the Trump Organization February 15, 2017 Dear Attorney General Schneiderman: We write to request that you investigate whether to bring proceedings to dissolve and revoke the charter of The Trump Organization, Inc. under Section 1101 of the Business Corporation Law. Judicial dissolution of a corporation should not be undertaken lightly. But this is not an ordinary case. By continuing to operate under Trump family ownership and control with President Trump in the White House, the Trump Organization flagrantly abuses its state-granted powers, contrary to the public policies of New York against corruption and conflicts of interest, and contrary to the U.S. Constitution. Furthermore, the Trump Organization has a history of alleged illegal, fraudulent, or abusive activity demonstrating that it has exceeded the authority conferred upon it by law and carried on its business in a persistently fraudulent or illegal manner. Its history, and that of its namesake, give every reason to expect that illegal activities will increase, not decrease, the longer that President Trump remains in the White House. Free Speech For People is a national non-partisan, non-profit 501(c)(3) organization that works to restore republican democracy to the people. Free Speech For People’s thousands of supporters around the country, including in New York, engage in education and non-partisan advocacy to encourage and support effective government of, by, and for the American people. -

Senate Democrats to Introduce Bill to Require President and Vice President to Fully Divest Personal Financial Conflicts of Interest

Senate Democrats to Introduce Bill to Require President and Vice President to Fully Divest Personal Financial Conflicts of Interest As Chairman and President of the Trump Organization, President-elect Donald J. Trump heads a “sprawling” international business network with “deep ties” to global financiers and foreign officials from countries around the globe, including China, Libya, and Turkey.1 Because of these ties, he will take office with “more potential business and financial conflicts of interest than any other president in U.S. history.”2 Unless he takes steps to address these conflicts, President-elect Trump will be in violation of the Constitution on “Day One” of his presidency.3 Article I, Section 9 of the Constitution prohibits officeholders, including the President,4 from “accept[ing] any present, emolument, office, or title, of any kind whatever, from any king, price, or foreign state.” Experts have concluded that “[c]orporations owned or controlled by a foreign government are presumptively foreign states under the Emoluments Clause.”5 Although the president and vice president are now exempt from many federal financial conflict of interest rules, the Office of Government Ethics has concluded that “the President and the Vice President should conduct themselves as if they were so bound” by them,6 and every president in the last 40 years has voluntarily complied. Yet President-elect Trump has resisted taking these steps, even boasting that “the president can’t have a conflict of interest.”7 He has announced no plans to divest from his businesses, announcing instead that his sons will manage the Trump Organization during his presidency.8 For decades, U.S. -

Fordham Journal of Corporate & Financial

Fordham Journal of Corporate & Financial Law Volume 15 Issue 1 Article 7 2010 Backdoor Bailout Disclosure: Must The Federal Reserve Disclose The Identities Of Its Borrowers Under The Freedom Of Information Act? Alexander Sellinger Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/jcfl Recommended Citation Alexander Sellinger, Backdoor Bailout Disclosure: Must The Federal Reserve Disclose The Identities Of Its Borrowers Under The Freedom Of Information Act?, 15 Fordham J. Corp. & Fin. L. 259 (2009). Available at: https://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/jcfl/vol15/iss1/7 This Note is brought to you for free and open access by FLASH: The Fordham Law Archive of Scholarship and History. It has been accepted for inclusion in Fordham Journal of Corporate & Financial Law by an authorized editor of FLASH: The Fordham Law Archive of Scholarship and History. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Backdoor Bailout Disclosure: Must The Federal Reserve Disclose The Identities Of Its Borrowers Under The Freedom Of Information Act? Cover Page Footnote J.D. Candidate, 2010, Fordham University School of Law; B.A., 2007 University of Virginia. The author is deeply indebted to Prof. Caroline Gentile for her guidance, insight and patience with this Note. He is also grateful for the hard work, honest feedback, and input of fellow members of the Journal of Corporate & Financial Law, especially Noe Burgos, Nicole Conner and Gary Varnavides. This note is available in Fordham Journal of Corporate & Financial Law: https://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/jcfl/vol15/iss1/ 7 NOTES BACKDOOR BAILOUT DISCLOSURE: MUST THE FEDERAL RESERVE DISCLOSE THE IDENTITIES OF ITS BORROWERS UNDER THE FREEDOM OF INFORMATION ACT? Alexander Sellinger* I. -

Rating Risk After the Subprime Mortgage Crisis: a User Fee Approach for Rating Agency Accountability

GW Law Faculty Publications & Other Works Faculty Scholarship 2008 Rating Risk after the Subprime Mortgage Crisis: A User Fee Approach for Rating Agency Accountability Jeffrey Manns George Washington University Law School, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.gwu.edu/faculty_publications Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Jeffrey Manns, Rating Risk after the Subprime Mortgage Crisis: A User Fee Approach for Rating Agency Accountability, 87 N.C. L. Rev. 1011 (2009). This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Scholarship at Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in GW Law Faculty Publications & Other Works by an authorized administrator of Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. RATING RISK AFTER THE SUBPRIME MORTGAGE CRISIS: A USER FEE APPROACH FOR RATING AGENCY ACCOUNTABILITY* JEFFREY MANNS** This Article argues that an absence of accountability and interconnections of interest between rating agencies and their debt-issuer clients fostered a system of lax ratings that provided false assurances on the risks posed by subprime mortgage- backed securities and collateralized debt obligations. It lays out an innovative, yet practical pathway for reform by suggesting how debt purchasers—the primary beneficiaries of ratings—may bear both the burdens and benefits of rating agency accountability by financing ratings through a Securities and Exchange Commission (“SEC”)-administered user fee system in exchange for enforceable rights. The SEC user fee system would require rating agencies both to bid for the right to rate debt issues and to assume certification and mandatory reporting duties to creditors. -

Document Filed by Ilene Richman

No. 20-222 In the Supreme Court of the United States GOLDMAN SACHS GROUP, INC., ET AL., PETITIONERS v. ARKANSAS TEACHER RETIREMENT SYSTEM, ET AL. ON WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE SECOND CIRCUIT JOINT APPENDIX (VOLUME 1; PAGES 1-400) KANNON K. SHANMUGAM THOMAS C. GOLDSTEIN PAUL, WEISS, RIFKIND, GOLDSTEIN & RUSSELL, P.C. WHARTON & GARRISON LLP 7475 Wisconsin Avenue 2001 K Street, N.W. Suite 850 Washington, DC 20006 Bethesda, MD 20814 (202) 223-7300 (202) 362-0636 [email protected] [email protected] Counsel of Record Counsel of Record for Petitioners for Respondents PETITION FOR A WRIT OF CERTIORARI FILED: AUGUST 21, 2020 CERTIORARI GRANTED: DECEMBER 11, 2020 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page VOLUME 1 Court of appeals docket entries (No. 18-3667) ................... 1 Court of appeals docket entries (No. 16-250) ..................... 5 District court docket entries (No. 10-3461) ........................ 8 Goldman Sachs 2007 Form 10-K: Conflicts Warning (D. Ct. Dkt. No. 78-6) .................................................... 23 Goldman Sachs 2007 Annual Report: Business Principles (D. Ct. Dkt. No. 143-16) ............................. 30 Financial Times, Markets & Investing, “Goldman’s risk control offers right example of governance,” Dec. 5, 2007 (D. Ct. Dkt. No. 193-20) .......................... 34 Dow Jones Business News, “13 Reasons Bush’s Bailout Won’t Stop Recession,” Dec. 11, 2007 (D. Ct. Dkt. No. 170-24) ................................................ 37 The Wall Street Journal, “How Goldman Won Big on Mortgage Meltdown,” Dec. 14, 2007 (front page) (D. Ct. Hearing Ex. T) ....................................... 42 The New York Times, Off the Shelf, “Economy’s Loss Was One Man’s Gain,” Dec.