The Eigerwand Direct1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

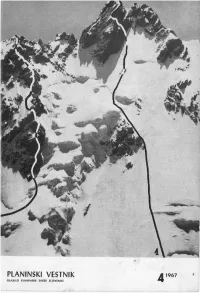

PV 1967 04.Pdf

poštnina plačana v gotovini VSEBINA: RAZMIŠLJANJA OB NAŠIH ODPRAVAH V KAVKAZ Ing. Pavle Šegula 145 KAVKAZ - MOST MED ALPAMI IN HIMALAJO EMO Janez Krušic 149 SLOVENSKO REBRO V SEVERNI STENI GESTOLE Celje Janez Krušic 157 SLOVENSKI STEBER V ULLU-AUSU Ing. Drago Zagorc 160 TIMOFEJEVA SMER V MIŽIRGIJU EMAJLIRNICA Janez Golob 161 METALNA INDUSTRIJA KAKO SE JE CVET SLOVENSKIH ALPINISTOV PRIVAJAL NA VIŠINO 5145 METROV ORODJARNA Boris Krivic 164 NJEGOV ZADNJI VZPON A. Kopinšek 168 IZDELUJE IN DOBAVLJA: K DISKUSIJI O NEKATERIH KRAŠKIH OBLIKAH VISO- KOGORSKEGA KRASA — frite z dodatki za izdelavo emajlov Dušan Novak 169 — emajlirano, pocinkano in alu posodo, sanitarno SEDEM DESETLETIJ PLANINSKEGA VESTNIKA in gospodinjsko opremo ter kovinsko embalažo (1895-1965) — toplotne naprave: radiatorje in kotle za cen- Evgen Lovšin 174 tralno in etažno ogrevanje GOZD JE NAŠ DOM 180 — odpreske in kolesa za motorna vozila ter od- DRUŠTVENE NOVICE 183 preske za rudarstvo ALPINISTIČNE NOVICE 184 — vse vrste orodij zo serijsko proizvodnjo: rezilna, IZ PLANINSKE LITERATURE 187 izsekovalna, vlečna, kombinirana in upogibna RAZGLED PO SVETU 188 orodja za predelavo pločevine, orodja za tlačni ANICA KUK liv in za proizvodnjo iz plastičnih mas, stekla Stanislav Gilič 191 in keramike NASLOVNA STRAN: — emajlira, pocinkuje in predeluje pločevine SEVERNO OSTENJE ULLU-AUS (4789 m) 1 - DIREKTNA SMER V SEVERNI STENI Tel.: 39-21 - Telegram: EMO-Celje - Telex: 0335-12 2 - SLOVENSKI STEBER - PRVENSTVENA SMER SEDEŽ: LJUBLJANA - VEVČE USTANOVLJENE LETA 1842 IZDELUJEJO SULFITNO CELULOZO I. a za vse vrste papirja PINOTAN - strojilni ekstrat BREZLESNI PAPIR za grafično in predelovalno in- dustrijo: za reprezentativne izdaje, umetniške slike, propagandne in turistične prospekte, za pisemski papir in kuverte najboljše kvalitete, za razne protokole, matične knjige, obrazce, -Planinski Vestnik« je glasilo Planinske zveze Slovenije / šolske zvezke in podobno Izdaja ga PZS - urejuje ga uredniški odbor. -

Pinnacle Club Jubilee Journal 1921-1971

© Pinnacle Club and Author All Rights Reserved PINNACLE CLUB JUBILEE JOURNAL 1921-1971 © Pinnacle Club and Author All Rights Reserved THE PINNACLE CLUB JOURNAL Fiftieth Anniversary Edition Published Edited by Gill Fuller No. 14 1969——70 © Pinnacle Club and Author All Rights Reserved THE PINNACLE CLUB OFFICERS AND COMMITTEE 1971 1921-1971 President: MRS. JANET ROGERS 8 The Penlee, Windsor Terrace, Penarth, Glamorganshire Vice-President: Miss MARGARET DARVALL The Coach House, Lyndhurst Terrace, London N.W.3 (Tel. 01-794 7133) Hon. Secretary: MRS. PAT DALEY 73 Selby Lane, Keyworth, Nottingham (Tel. 060-77 3334) Hon. Treasurer: MRS. ADA SHAW 25 Crowther Close, Beverley, Yorkshire (Tel. 0482 883826) Hon. Meets Secretary: Miss ANGELA FALLER 101 Woodland Hill, Whitkirk, Leeds 15 (Tel. 0532 648270) Hon Librarian: Miss BARBARA SPARK Highfield, College Road, Bangor, North Wales (Tel. Bangor 3330) Hon. Editor: Mrs. GILL FULLER Dog Bottom, Lee Mill Road, Hebden Bridge, Yorkshire. Hon. Business Editor: Miss ANGELA KELLY 27 The Avenue, Muswell Hill, London N.10 (Tel. 01-883 9245) Hon. Hut Secretary: MRS. EVELYN LEECH Ty Gelan, Llansadwrn, Anglesey, (Tel. Beaumaris 287) Hon. Assistant Hut Secretary: Miss PEGGY WILD Plas Gwynant Adventure School, Nant Gwynant, Caernarvonshire (Tel.Beddgelert212) Committee: Miss S. CRISPIN Miss G. MOFFAT MRS. S ANGELL MRS. J. TAYLOR MRS. N. MORIN Hon. Auditor: Miss ANNETTE WILSON © Pinnacle Club and Author All Rights Reserved CONTENTS Page Our Fiftieth Birthday ...... ...... Dorothy Pilley Richards 5 Wheel Full Circle ...... ...... Gwen M offat ...... 8 Climbing in the A.C.T. ...... Kath Hoskins ...... 14 The Early Days ..... ...... ...... Trilby Wells ...... 17 The Other Side of the Circus .... -

Mountaineering War and Peace at High Altitudes

Mountaineering War and Peace at High Altitudes 2–5 Sackville Street Piccadilly London W1S 3DP +44 (0)20 7439 6151 [email protected] https://sotherans.co.uk Mountaineering 1. ABBOT, Philip Stanley. Addresses at a Memorial Meeting of the Appalachian Mountain Club, October 21, 1896, and other 2. ALPINE SLIDES. A Collection of 72 Black and White Alpine papers. Reprinted from “Appalachia”, [Boston, Mass.], n.d. [1896]. £98 Slides. 1894 - 1901. £750 8vo. Original printed wrappers; pp. [iii], 82; portrait frontispiece, A collection of 72 slides 80 x 80mm, showing Alpine scenes. A 10 other plates; spine with wear, wrappers toned, a good copy. couple with cracks otherwise generally in very good condition. First edition. This is a memorial volume for Abbot, who died on 44 of the slides have no captioning. The remaining are variously Mount Lefroy in August 1896. The booklet prints Charles E. Fay’s captioned with initials, “CY”, “EY”, “LSY” AND “RY”. account of Abbot’s final climb, a biographical note about Abbot Places mentioned include Morteratsch Glacier, Gussfeldt Saddle, by George Herbert Palmer, and then reprints three of Abbot’s Mourain Roseg, Pers Ice Falls, Pontresina. Other comments articles (‘The First Ascent of Mount Hector’, ‘An Ascent of the include “Big lunch party”, “Swiss Glacier Scene No. 10” Weisshorn’, and ‘Three Days on the Zinal Grat’). additionally captioned by hand “Caution needed”. Not in the Alpine Club Library Catalogue 1982, Neate or Perret. The remaining slides show climbing parties in the Alps, including images of lady climbers. A fascinating, thus far unattributed, collection of Alpine climbing. -

Firestarters Summits of Desire Visionaries & Vandals

31465_Cover 12/2/02 9:59 am Page 2 ISSUE 25 - SPRING 2002 £2.50 Firestarters Choosing a Stove Summits of Desire International Year of Mountains FESTIVAL OF CLIMBING Visionaries & Vandals SKI-MOUNTAINEERING Grit Under Attack GUIDEBOOKS - THE FUTURE TUPLILAK • LEADERSHIP • METALLIC EQUIPMENT • NUTRITION FOREWORD... NEW SUMMITS s the new BMC Chief Officer, writing my first ever Summit Aforeword has been a strangely traumatic experience. After 5 years as BMC Access Officer - suddenly my head is on the block. Do I set out my vision for the future of the BMC or comment on the changing face of British climbing? Do I talk about the threats to the cliff and mountain envi- ronment and the challenges of new access legislation? How about the lessons learnt from foot and mouth disease or September 11th and the recent four fold hike in climbing wall insurance premiums? Big issues I’m sure you’ll agree - but for this edition I going to keep it simple and say a few words about the single most important thing which makes the BMC tick - volunteer involvement. Dave Turnbull - The new BMC Chief Officer Since its establishment in 1944 the BMC has relied heavily on volunteers and today the skills, experience and enthusi- District meetings spearheaded by John Horscroft and team asm that the many 100s of volunteers contribute to climb- are pointing the way forward on this front. These have turned ing and hill walking in the UK is immense. For years, stal- into real social occasions with lively debates on everything warts in the BMC’s guidebook team has churned out quality from bolts to birds, with attendances of up to 60 people guidebooks such as Chatsworth and On Peak Rock and the and lively slideshows to round off the evenings - long may BMC is firmly committed to getting this important Commit- they continue. -

CC J Inners 168Pp.Indd

theclimbers’club Journal 2011 theclimbers’club Journal 2011 Contents ALPS AND THE HIMALAYA THE HOME FRONT Shelter from the Storm. By Dick Turnbull P.10 A Midwinter Night’s Dream. By Geoff Bennett P.90 Pensioner’s Alpine Holiday. By Colin Beechey P.16 Further Certifi cation. By Nick Hinchliffe P.96 Himalayan Extreme for Beginners. By Dave Turnbull P.23 Welsh Fix. By Sarah Clough P.100 No Blends! By Dick Isherwood P.28 One Flew Over the Bilberry Ledge. By Martin Whitaker P.105 Whatever Happened to? By Nick Bullock P.108 A Winter Day at Harrison’s. By Steve Dean P.112 PEOPLE Climbing with Brasher. By George Band P.36 FAR HORIZONS The Dragon of Carnmore. By Dave Atkinson P.42 Climbing With Strangers. By Brian Wilkinson P.48 Trekking in the Simien Mountains. By Rya Tibawi P.120 Climbing Infl uences and Characters. By James McHaffi e P.53 Spitkoppe - an Old Climber’s Dream. By Ian Howell P.128 Joe Brown at Eighty. By John Cleare P.60 Madagascar - an African Yosemite. By Pete O’Donovan P.134 Rock Climbing around St Catherine’s Monastery in the Sinai Desert. By Malcolm Phelps P.142 FIRST ASCENTS Summer Shale in Cornwall. By Mick Fowler P.68 OBITUARIES A Desert Nirvana. By Paul Ross P.74 The First Ascent of Vector. By Claude Davies P.78 George Band OBE. 1929 - 2011 P.150 Three Rescues and a Late Dinner. By Tony Moulam P.82 Alan Blackshaw OBE. 1933 - 2011 P.154 Ben Wintringham. 1947 - 2011 P.158 Chris Astill. -

1976 Bicentennial Mckinley South Buttress Expedition

THE MOUNTAINEER • Cover:Mowich Glacier Art Wolfe The Mountaineer EDITORIAL COMMITTEE Verna Ness, Editor; Herb Belanger, Don Brooks, Garth Ferber. Trudi Ferber, Bill French, Jr., Christa Lewis, Mariann Schmitt, Paul Seeman, Loretta Slater, Roseanne Stukel, Mary Jane Ware. Writing, graphics and photographs should be submitted to the Annual Editor, The Mountaineer, at the address below, before January 15, 1978 for consideration. Photographs should be black and white prints, at least 5 x 7 inches, with caption and photo grapher's name on back. Manuscripts should be typed double· spaced, with at least 1 Y:z inch margins, and include writer's name, address and phone number. Graphics should have caption and artist's name on back. Manuscripts cannot be returned. Properly identified photographs and graphics will be returnedabout June. Copyright © 1977, The Mountaineers. Entered as second·class matter April8, 1922, at Post Office, Seattle, Washington, under the act of March 3, 1879. Published monthly, except July, when semi-monthly, by The Mountaineers, 719 Pike Street,Seattle, Washington 98101. Subscription price, monthly bulletin and annual, $6.00 per year. ISBN 0-916890-52-X 2 THE MOUNTAINEERS PURPOSES To explore and study the mountains, forests, and watercourses of the Northwest; To gather into permanentform the history and tra ditions of thisregion; To preserve by the encouragement of protective legislation or otherwise the natural beauty of NorthwestAmerica; To make expeditions into these regions in fulfill ment of the above purposes; To encourage a spirit of good fellowship among all loversof outdoor life. 0 � . �·' ' :···_I·:_ Red Heather ' J BJ. Packard 3 The Mountaineer At FerryBasin B. -

Taternik 3-4 1965

http://pza.org.pl SPIS TREŚCI Oni wprowadzili nas w Tatry (Ryszard Ziemak) 73 „Polacy na szczytach świata" (Jacek Kolbuszewski) 74 Spitsbergen 1965. Wyprawa Koła Poz nańskiego (Ryszard W, Schramm). 77 Aiguille Verte w zimie (Jerzy Michal ski) • 83 Zima 1964/1965 w Tatrach 85 Porachunki z latem (Jerzy Jagodziński) 86 W najtrudniejszej ścianie Tatr (Kazi mierz Głazek) 89 Spotkanie UIAA na Hali Gąsienico wej (Bogdan Mac) 91 Szwajcaria — Polska (Jan Kowalczyk i Antoni Janik) 94 Lato wokół Mont Blanc (Janusz Kur- czab) . 95 Obóz letni w Chamonix 1965 (Jerzy Warteresiewicz) 93 Na stażu w ENSA, 1965 (Maciej Popko) 99 W górach Grecji (Maciej Kozłowski) 100 Casus Gliwice (Józef Nyka) 101 Alpiniści angielscy w Tatrach (Andrzej Kuś) 102 Zginął Lionel Terray (Andrzej Pacz kowski) 105 Problemy w Elbsandsteingebirge (Józef Nyka) 106 Dr Kazimierz Saysse-Tobiczyk, naj młodszy ze starszych panów (Adam Chowański) 107 Drobiazgi historyczne 111 Taternictwo jaskiniowe 112 Skalne drogi w Tatrach 114 Nowe drogi w Dolomitach 120 Itineraria alpejskie 122 Narciarstwo wysokogórskie 123 Karta żałobna 124 Z życia Klubu Wysokogórskiego . 126 Z piśmiennictwa 129 Notatki, ciekawostki 130 Sprostowania i uzupełnienia 134 Przednia okładka: Członek GOPR, Zbigniew Jabłoński, podczas wspinaczki na Mnichu. Fot. Ryszard Ziemak Obok: Kozi Wierch znad Czarnego Stawu pod Kościelcem. Fot. Ryszard Ziemak http://pza.org.pl Taternik Organ Klubu Wysokogórskiego Rocznik 41 Warszawa, 1965 nr 3 - 4 (188 - 189 Oni ujproiuadzili nas UJ Tatry W dniach 23 i 24 października 1965 r. sy. Aktualne wykazy nazwisk przynosiły odbyły się w Zakopanem centralne uroczy drukowane przewodniki, a także roczniki stości jubileuszowe przewodnictwa tatrzań „Pamiętnika Towarzystwa Tatrzańskiego". -

Appalachia Alpina

Appalachia Volume 71 Number 2 Summer/Fall 2020: Unusual Pioneers Article 16 2020 Alpina Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.dartmouth.edu/appalachia Part of the Nonfiction Commons Recommended Citation (2020) "Alpina," Appalachia: Vol. 71 : No. 2 , Article 16. Available at: https://digitalcommons.dartmouth.edu/appalachia/vol71/iss2/16 This In Every Issue is brought to you for free and open access by Dartmouth Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Appalachia by an authorized editor of Dartmouth Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Alpina A semiannual review of mountaineering in the greater ranges The 8,000ers The major news of 2019 was that Nirmal (Nims) Purja, from Nepal, climbed all fourteen 8,000-meter peaks in under seven months. The best previous time was a bit under eight years. Records are made to be broken, but rarely are they smashed like this. Here, from the Kathmandu Post, is the summary: Annapurna, 8,091 meters, Nepal, April 23 Dhaulagiri, 8,167 meters, Nepal, May 12 Kangchenjunga, 8,586 meters, Nepal, May 15 Everest, 8,848 meters, Nepal, May 22 Lhotse, 8,516 meters, Nepal, May 22 Makalu, 8,481 meters, Nepal, May 24 Nanga Parbat, 8,125 meters, Pakistan, July 3 Gasherbrum I, 8,080 meters, Pakistan, July 15 Gasherbrum II, 8,035 meters, Pakistan, July 18 K2, 8,611 meters, Pakistan, July 24 Broad Peak, 8,047 meters, Pakistan, July 26 Cho Oyu 8,201 meters, China/Nepal, September 23 Manaslu, 8,163 meters, Nepal, September 27 Shishapangma, 8,013 meters, China, October 29 He reached the summits of Everest, Lhotse, and Makalu in an astounding three days. -

ASIAN ALPINE E-NEWS Issue No 75. September 2020

ASIAN ALPINE E-NEWS Issue No 75. September 2020 C CONTENTS All-Afghan Team with two Women Climb Nation's Highest Peak Noshakh 7492m of Afghanistan Page 2 ~ 6 Himalayan Club E-Letter vol. 40 Page 7 ~ 43 1 All-Afghan Team, with 2 Women Climb Nation's Highest – Peak Noshakh 7492m The team members said they did their exercises for the trip in Panjshir, Salang and other places for one month ahead of their journey. Related News • Female 30K Cycling Race Starts in Afghanistan • Afghan Female Cyclist in France Prepares for Olympics Fatima Sultani, an 18-year-old Afghan woman, spoke to TOLOnews and said she and companions reached the summit of Noshakh in the Hindu Kush mountains, which is the highest peak in Afghanistan at 7,492 meters. 1 The group claims to be the first all-Afghan team to reach the summit. Fatima was joined by eight other mountaineers, including two girls and six men, on the 17-day journey. They began the challenging trip almost a month ago from Kabul. Noshakh is located in the Wakhan corridor in the northeastern province of Badakhshan. “Mountaineering is a strong sport, but we can conquer the summit if we are provided the gear,” Sultani said.The team members said they did their exercises for the trip in Panjshir, Salang and other places for one month ahead of their journey. “We made a plan with our friends to conquer Noshakh summit without foreign support as the first Afghan team,” said Ali Akbar Sakhi, head of the team. The mountaineers said their trip posed challenge but they overcame them. -

The Mountaineering Experience: Determining the Critical Factors and Assessing Management Practices

University of Calgary PRISM: University of Calgary's Digital Repository Graduate Studies The Vault: Electronic Theses and Dissertations 2014-09-16 The Mountaineering Experience: Determining the Critical Factors and Assessing Management Practices Benjamin, Mary Wilder Benjamin, M. W. (2014). The Mountaineering Experience: Determining the Critical Factors and Assessing Management Practices (Unpublished master's thesis). University of Calgary, Calgary, AB. doi:10.11575/PRISM/28251 http://hdl.handle.net/11023/1767 master thesis University of Calgary graduate students retain copyright ownership and moral rights for their thesis. You may use this material in any way that is permitted by the Copyright Act or through licensing that has been assigned to the document. For uses that are not allowable under copyright legislation or licensing, you are required to seek permission. Downloaded from PRISM: https://prism.ucalgary.ca UNIVERSITY OF CALGARY The Mountaineering Experience: Determining the Critical Factors and Assessing Management Practices by Mary Wilder Benjamin A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ENVIRONMENTAL DESIGN FACULTY OF ENVIRONMENTAL DESIGN CALGARY, ALBERTA SEPTEMBER, 2014 © Mary Wilder Benjamin 2014 Abstract Recreational mountaineering is a complex pursuit that continues to evolve with respect to demographics, participant numbers, methods, equipment, and the nature of the experience sought. The activity often occurs in protected areas where agency managers are charged with the inherently conflicting mandate of protecting the natural environment and facilitating high quality recreational experiences. Effective management of such mountaineering environs is predicated on meaningful understanding of the users’ motivations, expectations and behaviours. -

In Memoriam 1981

In Memoriam Introduction Geoffrey Templeman Since the last Journal was published, 9 of our members have died, the list being as follows: Donald Mill; Marjorie Garrod; Charles John Morris; Mark Pasteur; Reginald Mountain; Thomas MacKinnon; Arnold Pines; Richard Grant and Archibald Scott. It also appears that no mention was made in the Journal of the death ofour distinguished Honorary Member Henry de Segogne in 1979:-ifanyone would like to write a tribute, I will be very pleased to print it next year. My request for any further tributes for Lucien Devies last year was promptly answered and they are included here. Also included from previous years are full obituaries of Sir Percy Wyn Harris, Dr John Lewis and Nicolas Jaeger, whilst mention should also be made here of the recent death of Sir Michael Postan, a former member of the club. I would once again like to express my sincere thanks to all who have helped in producing the tributes that follow-without their help, the Journal would be the poorer. It has not been possible to obtain obituaries for one or two members and my own short notes must suffice for the following. Reginald WilIiam Mountain, who joined the club in 1941, died last year at the age of 81. His application for membership shows that he started climbing in the Alps in 1924 and completed a number of standard courses in the Bernese Oberland and Mont Blanc region, mostly with guides. ArchibaldJames Scott died in October, 1981, aged 79, having been a member of the club for 46 years. -

Journal 1987

THE ASSOCIATION OF BRITISH MEMBERS OF THE SWISS ALPINE CLUB JOURNAL 1987 CONTENTS PAGE Diary for 1987 3 Editorial 5 Unveiling of the Bernard Hiner Plaque at Zermatt by Rudolf Loewy 7 Reports of Members' activities 8 Association Activities 15 The A.G.M. 15 Assodation Accounts 17 The Annual Dinner 19 The Outdoor Meets 20 Obituaries 26 F.Roy Crepin 26 Ian M. Haig 28 John M. Hartog 27 Noel Peskett 27 Mary-Elizabeth Solari 27 Book Reviews 29 List of Past and Present Officers 33 List of Members 36 Other useful addresses 98 Official Addresses of the S.A.C. 49 Officers of the Association 1987 Back Cover DIARY FOR 1987 • December 20 1986 - • • 11 January 4 1987 Patterdale January 23-25 Perthshire. A. Andrews. January 28 Fondue Party. John Whyte on "Boots, Bears and Banff". February 6-8 Northern Dinner Meet. Patterdale, Glenridding. Brooke Midgley. February 27 - Perthshire. A. Andrews March 1. March 18 Lecture meet. Les Swindin on "Some favourite Alpine climbs". March 20-22 Perthshire. A. Andrews. March 27-28 Patterdale, ABMSAC maintenance meet. Don Hodge. April 17-20 Easter meet at Patterdale. May 2-4 Bank Holiday meet at Patterdale. May 20 Buffet Party May 23-30 Shieldaig, Torridon. A. Andrews. July 18 - August 1 ABMS AC / AC Alpine meet . Two weeks at Les Frosserands (near Argentiere), one week in Courmayeur. M. Pinney. August - 2nd, 3rd ABMSAC Alpine meet. Mont Blanc area. and 9th weeks. H.D. Archer. September 20 Alpine reunion slide show. August 29-31 Bank Holiday meet at Patterdale. October 2-4 Buffet Party, Patterdale Marion Porteous.