Dougal Haston - a Tribute1 J

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PV 1967 04.Pdf

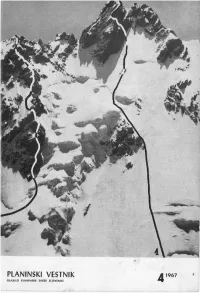

poštnina plačana v gotovini VSEBINA: RAZMIŠLJANJA OB NAŠIH ODPRAVAH V KAVKAZ Ing. Pavle Šegula 145 KAVKAZ - MOST MED ALPAMI IN HIMALAJO EMO Janez Krušic 149 SLOVENSKO REBRO V SEVERNI STENI GESTOLE Celje Janez Krušic 157 SLOVENSKI STEBER V ULLU-AUSU Ing. Drago Zagorc 160 TIMOFEJEVA SMER V MIŽIRGIJU EMAJLIRNICA Janez Golob 161 METALNA INDUSTRIJA KAKO SE JE CVET SLOVENSKIH ALPINISTOV PRIVAJAL NA VIŠINO 5145 METROV ORODJARNA Boris Krivic 164 NJEGOV ZADNJI VZPON A. Kopinšek 168 IZDELUJE IN DOBAVLJA: K DISKUSIJI O NEKATERIH KRAŠKIH OBLIKAH VISO- KOGORSKEGA KRASA — frite z dodatki za izdelavo emajlov Dušan Novak 169 — emajlirano, pocinkano in alu posodo, sanitarno SEDEM DESETLETIJ PLANINSKEGA VESTNIKA in gospodinjsko opremo ter kovinsko embalažo (1895-1965) — toplotne naprave: radiatorje in kotle za cen- Evgen Lovšin 174 tralno in etažno ogrevanje GOZD JE NAŠ DOM 180 — odpreske in kolesa za motorna vozila ter od- DRUŠTVENE NOVICE 183 preske za rudarstvo ALPINISTIČNE NOVICE 184 — vse vrste orodij zo serijsko proizvodnjo: rezilna, IZ PLANINSKE LITERATURE 187 izsekovalna, vlečna, kombinirana in upogibna RAZGLED PO SVETU 188 orodja za predelavo pločevine, orodja za tlačni ANICA KUK liv in za proizvodnjo iz plastičnih mas, stekla Stanislav Gilič 191 in keramike NASLOVNA STRAN: — emajlira, pocinkuje in predeluje pločevine SEVERNO OSTENJE ULLU-AUS (4789 m) 1 - DIREKTNA SMER V SEVERNI STENI Tel.: 39-21 - Telegram: EMO-Celje - Telex: 0335-12 2 - SLOVENSKI STEBER - PRVENSTVENA SMER SEDEŽ: LJUBLJANA - VEVČE USTANOVLJENE LETA 1842 IZDELUJEJO SULFITNO CELULOZO I. a za vse vrste papirja PINOTAN - strojilni ekstrat BREZLESNI PAPIR za grafično in predelovalno in- dustrijo: za reprezentativne izdaje, umetniške slike, propagandne in turistične prospekte, za pisemski papir in kuverte najboljše kvalitete, za razne protokole, matične knjige, obrazce, -Planinski Vestnik« je glasilo Planinske zveze Slovenije / šolske zvezke in podobno Izdaja ga PZS - urejuje ga uredniški odbor. -

Pinnacle Club Jubilee Journal 1921-1971

© Pinnacle Club and Author All Rights Reserved PINNACLE CLUB JUBILEE JOURNAL 1921-1971 © Pinnacle Club and Author All Rights Reserved THE PINNACLE CLUB JOURNAL Fiftieth Anniversary Edition Published Edited by Gill Fuller No. 14 1969——70 © Pinnacle Club and Author All Rights Reserved THE PINNACLE CLUB OFFICERS AND COMMITTEE 1971 1921-1971 President: MRS. JANET ROGERS 8 The Penlee, Windsor Terrace, Penarth, Glamorganshire Vice-President: Miss MARGARET DARVALL The Coach House, Lyndhurst Terrace, London N.W.3 (Tel. 01-794 7133) Hon. Secretary: MRS. PAT DALEY 73 Selby Lane, Keyworth, Nottingham (Tel. 060-77 3334) Hon. Treasurer: MRS. ADA SHAW 25 Crowther Close, Beverley, Yorkshire (Tel. 0482 883826) Hon. Meets Secretary: Miss ANGELA FALLER 101 Woodland Hill, Whitkirk, Leeds 15 (Tel. 0532 648270) Hon Librarian: Miss BARBARA SPARK Highfield, College Road, Bangor, North Wales (Tel. Bangor 3330) Hon. Editor: Mrs. GILL FULLER Dog Bottom, Lee Mill Road, Hebden Bridge, Yorkshire. Hon. Business Editor: Miss ANGELA KELLY 27 The Avenue, Muswell Hill, London N.10 (Tel. 01-883 9245) Hon. Hut Secretary: MRS. EVELYN LEECH Ty Gelan, Llansadwrn, Anglesey, (Tel. Beaumaris 287) Hon. Assistant Hut Secretary: Miss PEGGY WILD Plas Gwynant Adventure School, Nant Gwynant, Caernarvonshire (Tel.Beddgelert212) Committee: Miss S. CRISPIN Miss G. MOFFAT MRS. S ANGELL MRS. J. TAYLOR MRS. N. MORIN Hon. Auditor: Miss ANNETTE WILSON © Pinnacle Club and Author All Rights Reserved CONTENTS Page Our Fiftieth Birthday ...... ...... Dorothy Pilley Richards 5 Wheel Full Circle ...... ...... Gwen M offat ...... 8 Climbing in the A.C.T. ...... Kath Hoskins ...... 14 The Early Days ..... ...... ...... Trilby Wells ...... 17 The Other Side of the Circus .... -

Mountaineering Books Under £10

Mountaineering Books Under £10 AUTHOR TITLE PUBLISHER EDITION CONDITION DESCRIPTION REFNo PRICE AA Publishing Focus On The Peak District AA Publishing 1997 First Edition 96pp, paperback, VG Includes walk and cycle rides. 49344 £3 Abell Ed My Father's Keep. A Journey Of Ed Abell 2013 First Edition 106pp, paperback, Fine copy The book is a story of hope for 67412 £9 Forgiveness Through The Himalaya. healing of our most complicated family relationships through understanding, compassion, and forgiveness, peace for ourselves despite our inability to save our loved ones from the ravages of addiction, and strength for the arduous yet enriching journey. Abraham Guide To Keswick & The Vale Of G.P. Abraham Ltd 20 page booklet 5890 £8 George D. Derwentwater Abraham Modern Mountaineering Methuen & Co 1948 3rd Edition 198pp, large bump to head of spine, Classic text from the rock climbing 5759 £6 George D. Revised slight slant to spine, Good in Good+ pioneer, covering the Alps, North dw. Wales and The Lake District. Abt Julius Allgau Landshaft Und Menschen Bergverlag Rudolf 1938 First Edition 143pp, inscription, text in German, VG- 10397 £4 Rother in G chipped dw. Aflalo F.G. Behind The Ranges. Parentheses Of Martin Secker 1911 First Edition 284pp, 14 illusts, original green cloth, Aflalo's wide variety of travel 10382 £8 Travel. boards are slightly soiled and marked, experiences. worn spot on spine, G+. Ahluwalia Major Higher Than Everest. Memoirs of a Vikas Publishing 1973 First Edition 188pp, Fair in Fair dw. Autobiography of one of the world's 5743 £9 H.P.S. Mountaineer House most famous mountaineers. -

CC J Inners 168Pp.Indd

theclimbers’club Journal 2011 theclimbers’club Journal 2011 Contents ALPS AND THE HIMALAYA THE HOME FRONT Shelter from the Storm. By Dick Turnbull P.10 A Midwinter Night’s Dream. By Geoff Bennett P.90 Pensioner’s Alpine Holiday. By Colin Beechey P.16 Further Certifi cation. By Nick Hinchliffe P.96 Himalayan Extreme for Beginners. By Dave Turnbull P.23 Welsh Fix. By Sarah Clough P.100 No Blends! By Dick Isherwood P.28 One Flew Over the Bilberry Ledge. By Martin Whitaker P.105 Whatever Happened to? By Nick Bullock P.108 A Winter Day at Harrison’s. By Steve Dean P.112 PEOPLE Climbing with Brasher. By George Band P.36 FAR HORIZONS The Dragon of Carnmore. By Dave Atkinson P.42 Climbing With Strangers. By Brian Wilkinson P.48 Trekking in the Simien Mountains. By Rya Tibawi P.120 Climbing Infl uences and Characters. By James McHaffi e P.53 Spitkoppe - an Old Climber’s Dream. By Ian Howell P.128 Joe Brown at Eighty. By John Cleare P.60 Madagascar - an African Yosemite. By Pete O’Donovan P.134 Rock Climbing around St Catherine’s Monastery in the Sinai Desert. By Malcolm Phelps P.142 FIRST ASCENTS Summer Shale in Cornwall. By Mick Fowler P.68 OBITUARIES A Desert Nirvana. By Paul Ross P.74 The First Ascent of Vector. By Claude Davies P.78 George Band OBE. 1929 - 2011 P.150 Three Rescues and a Late Dinner. By Tony Moulam P.82 Alan Blackshaw OBE. 1933 - 2011 P.154 Ben Wintringham. 1947 - 2011 P.158 Chris Astill. -

1976 Bicentennial Mckinley South Buttress Expedition

THE MOUNTAINEER • Cover:Mowich Glacier Art Wolfe The Mountaineer EDITORIAL COMMITTEE Verna Ness, Editor; Herb Belanger, Don Brooks, Garth Ferber. Trudi Ferber, Bill French, Jr., Christa Lewis, Mariann Schmitt, Paul Seeman, Loretta Slater, Roseanne Stukel, Mary Jane Ware. Writing, graphics and photographs should be submitted to the Annual Editor, The Mountaineer, at the address below, before January 15, 1978 for consideration. Photographs should be black and white prints, at least 5 x 7 inches, with caption and photo grapher's name on back. Manuscripts should be typed double· spaced, with at least 1 Y:z inch margins, and include writer's name, address and phone number. Graphics should have caption and artist's name on back. Manuscripts cannot be returned. Properly identified photographs and graphics will be returnedabout June. Copyright © 1977, The Mountaineers. Entered as second·class matter April8, 1922, at Post Office, Seattle, Washington, under the act of March 3, 1879. Published monthly, except July, when semi-monthly, by The Mountaineers, 719 Pike Street,Seattle, Washington 98101. Subscription price, monthly bulletin and annual, $6.00 per year. ISBN 0-916890-52-X 2 THE MOUNTAINEERS PURPOSES To explore and study the mountains, forests, and watercourses of the Northwest; To gather into permanentform the history and tra ditions of thisregion; To preserve by the encouragement of protective legislation or otherwise the natural beauty of NorthwestAmerica; To make expeditions into these regions in fulfill ment of the above purposes; To encourage a spirit of good fellowship among all loversof outdoor life. 0 � . �·' ' :···_I·:_ Red Heather ' J BJ. Packard 3 The Mountaineer At FerryBasin B. -

Taternik 3-4 1965

http://pza.org.pl SPIS TREŚCI Oni wprowadzili nas w Tatry (Ryszard Ziemak) 73 „Polacy na szczytach świata" (Jacek Kolbuszewski) 74 Spitsbergen 1965. Wyprawa Koła Poz nańskiego (Ryszard W, Schramm). 77 Aiguille Verte w zimie (Jerzy Michal ski) • 83 Zima 1964/1965 w Tatrach 85 Porachunki z latem (Jerzy Jagodziński) 86 W najtrudniejszej ścianie Tatr (Kazi mierz Głazek) 89 Spotkanie UIAA na Hali Gąsienico wej (Bogdan Mac) 91 Szwajcaria — Polska (Jan Kowalczyk i Antoni Janik) 94 Lato wokół Mont Blanc (Janusz Kur- czab) . 95 Obóz letni w Chamonix 1965 (Jerzy Warteresiewicz) 93 Na stażu w ENSA, 1965 (Maciej Popko) 99 W górach Grecji (Maciej Kozłowski) 100 Casus Gliwice (Józef Nyka) 101 Alpiniści angielscy w Tatrach (Andrzej Kuś) 102 Zginął Lionel Terray (Andrzej Pacz kowski) 105 Problemy w Elbsandsteingebirge (Józef Nyka) 106 Dr Kazimierz Saysse-Tobiczyk, naj młodszy ze starszych panów (Adam Chowański) 107 Drobiazgi historyczne 111 Taternictwo jaskiniowe 112 Skalne drogi w Tatrach 114 Nowe drogi w Dolomitach 120 Itineraria alpejskie 122 Narciarstwo wysokogórskie 123 Karta żałobna 124 Z życia Klubu Wysokogórskiego . 126 Z piśmiennictwa 129 Notatki, ciekawostki 130 Sprostowania i uzupełnienia 134 Przednia okładka: Członek GOPR, Zbigniew Jabłoński, podczas wspinaczki na Mnichu. Fot. Ryszard Ziemak Obok: Kozi Wierch znad Czarnego Stawu pod Kościelcem. Fot. Ryszard Ziemak http://pza.org.pl Taternik Organ Klubu Wysokogórskiego Rocznik 41 Warszawa, 1965 nr 3 - 4 (188 - 189 Oni ujproiuadzili nas UJ Tatry W dniach 23 i 24 października 1965 r. sy. Aktualne wykazy nazwisk przynosiły odbyły się w Zakopanem centralne uroczy drukowane przewodniki, a także roczniki stości jubileuszowe przewodnictwa tatrzań „Pamiętnika Towarzystwa Tatrzańskiego". -

Appalachia Alpina

Appalachia Volume 71 Number 2 Summer/Fall 2020: Unusual Pioneers Article 16 2020 Alpina Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.dartmouth.edu/appalachia Part of the Nonfiction Commons Recommended Citation (2020) "Alpina," Appalachia: Vol. 71 : No. 2 , Article 16. Available at: https://digitalcommons.dartmouth.edu/appalachia/vol71/iss2/16 This In Every Issue is brought to you for free and open access by Dartmouth Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Appalachia by an authorized editor of Dartmouth Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Alpina A semiannual review of mountaineering in the greater ranges The 8,000ers The major news of 2019 was that Nirmal (Nims) Purja, from Nepal, climbed all fourteen 8,000-meter peaks in under seven months. The best previous time was a bit under eight years. Records are made to be broken, but rarely are they smashed like this. Here, from the Kathmandu Post, is the summary: Annapurna, 8,091 meters, Nepal, April 23 Dhaulagiri, 8,167 meters, Nepal, May 12 Kangchenjunga, 8,586 meters, Nepal, May 15 Everest, 8,848 meters, Nepal, May 22 Lhotse, 8,516 meters, Nepal, May 22 Makalu, 8,481 meters, Nepal, May 24 Nanga Parbat, 8,125 meters, Pakistan, July 3 Gasherbrum I, 8,080 meters, Pakistan, July 15 Gasherbrum II, 8,035 meters, Pakistan, July 18 K2, 8,611 meters, Pakistan, July 24 Broad Peak, 8,047 meters, Pakistan, July 26 Cho Oyu 8,201 meters, China/Nepal, September 23 Manaslu, 8,163 meters, Nepal, September 27 Shishapangma, 8,013 meters, China, October 29 He reached the summits of Everest, Lhotse, and Makalu in an astounding three days. -

Cairngorm Club Library List Oct2020 Edited Kjt30oct2020

Cairngorm Club Library Holding Re-Catalogued at Kings College Special Collections October 2020 To find current Library reference data, availability, etc., search title, author, etc. in the University Catalogue: see www.abdn.ac.uk/library Type / Creator / Imprint title Johnson, Samuel, (London : Strahan & Cadell, 1775.) A journey to the Western Islands of Scotland. Taylor, George, (London : the authors, 1776) Taylor and Skinner's survey and maps of the roads of North Britain or Scotland. Boswell, James, (London : Dilly, 1785.) The journal of a tour to the Hebrides, with Samuel Johnson, LL. D. / . Grant, Anne MacVicar, (Edinburgh : Grant, 1803) Poems on various subjects. Bristed, John. (London : Wallis, 1803.) A predestrian tour through part of the Highlands of Scotland, in 1801. Campbell, Alexander, (London : Vernor & Hood, 1804) The Grampians desolate : a poem. Grant, Anne MacVicar, (London : Longman, 1806.) Letters from the mountains; being the real correspondence of a lady between the years 1773 and Keith, George Skene, (Aberdeen : Brown, 1811.) A general view of the agriculture of Aberdeenshire. Robson, George Fennell. (London : The author, 1814) Scenery of the Grampian Mountains; illustrated by forty etchings in the soft ground. Hogg, James, (Edinburgh : Blackwood & Murray, 1819.) The Queen's wake : a legendary poem. Sketches of the character, manners, and present state of the Highlanders of Scotland : with details Stewart, David, (Edinburgh : Constable, 1822.) of the military service of the Highland regiments. The Highlands and Western Isles of Scotland, containing descriptions of their scenery and antiquities, with an account of the political history and ancient manners, and of the origin, Macculloch, John, (London : Longman, Hurst, Rees, Orme, language, agriculture, economy, music, present condition of the people, &c. -

Journal 1987

THE ASSOCIATION OF BRITISH MEMBERS OF THE SWISS ALPINE CLUB JOURNAL 1987 CONTENTS PAGE Diary for 1987 3 Editorial 5 Unveiling of the Bernard Hiner Plaque at Zermatt by Rudolf Loewy 7 Reports of Members' activities 8 Association Activities 15 The A.G.M. 15 Assodation Accounts 17 The Annual Dinner 19 The Outdoor Meets 20 Obituaries 26 F.Roy Crepin 26 Ian M. Haig 28 John M. Hartog 27 Noel Peskett 27 Mary-Elizabeth Solari 27 Book Reviews 29 List of Past and Present Officers 33 List of Members 36 Other useful addresses 98 Official Addresses of the S.A.C. 49 Officers of the Association 1987 Back Cover DIARY FOR 1987 • December 20 1986 - • • 11 January 4 1987 Patterdale January 23-25 Perthshire. A. Andrews. January 28 Fondue Party. John Whyte on "Boots, Bears and Banff". February 6-8 Northern Dinner Meet. Patterdale, Glenridding. Brooke Midgley. February 27 - Perthshire. A. Andrews March 1. March 18 Lecture meet. Les Swindin on "Some favourite Alpine climbs". March 20-22 Perthshire. A. Andrews. March 27-28 Patterdale, ABMSAC maintenance meet. Don Hodge. April 17-20 Easter meet at Patterdale. May 2-4 Bank Holiday meet at Patterdale. May 20 Buffet Party May 23-30 Shieldaig, Torridon. A. Andrews. July 18 - August 1 ABMS AC / AC Alpine meet . Two weeks at Les Frosserands (near Argentiere), one week in Courmayeur. M. Pinney. August - 2nd, 3rd ABMSAC Alpine meet. Mont Blanc area. and 9th weeks. H.D. Archer. September 20 Alpine reunion slide show. August 29-31 Bank Holiday meet at Patterdale. October 2-4 Buffet Party, Patterdale Marion Porteous. -

British Everest Expedition SW Face 1975 Peter Boardman and Ronnie Richards

British Everest expedition SW face 1975 Peter Boardman and Ronnie Richards It was a strange sensation to be lying prostrate with heat at nearly 6700 m, rain apparently floating down through the sultry glaring mist outside. Few people had been in the Cwm by the beginning of September and the old hands ruefully remembered November conditions in 1972, hence the gleeful graffiti on the boudoir walls of our lone Camp 2 superbox, exhorting: 'Climb Everest in September, be at home by October'. Express trains rumbled and roared incessantly from Lhotse above, the W Ridge left and uptse below; all movement on the mountain was out of the question, so we could indulge in continuous brews and lethargic inactivity. One's mind drifted back over the previous few days, traversing terrain made familiar, even legendary in the last 20 years. Base Camp, established on 22 August in its field of rubble, and a familiarisation with successive sections of the Ice-Fall on the following days, as the route through to a site for Camp 1 was prospected and made safe for subsequent traffic. Ice-Fall Sirdar Phurkipa, chief road mender and survivor of countless journeys up the Ice Fall, had shown his approval, white tooth flashing enthusiastically at the unusually benign conditions of the Ice-Fall this time of year. Tottering horrors apparently absent, the main areas of concern were the 'Egg-Shell', a short, flattish area surrounded by huge holes and crevasses, seemingly liable to sudden collapse, and a short distance above, 'Death Valley', hot and a possible channel for big avalanches peeling off the flank of the W Ridge. -

Liste Des Courses De Claudio Barbier

Elenco delle Vie percorse da Claudio in montagna Liste des courses en montagne de Claudio Liste revue par Pascale Binamé et recorrigée par Alberto Dorigatti en 2010. Claudio n’a pas écrit un “livre de courses” à proprement parler. À sa mort j’ai trouvé un tiroir plein de notes, cartons à bière, feuillets et carnets. Dès 1977 j’ai commencé à éplucher ce matériel et une première “liste de courses” a été publiée en 1995 dans mon livre “La Via del Drago”. Ce n’est que lors de sa deuxième édition en 2008 que j’ai remarqué que d’importantes erreurs se sont glissées surtout dans les dates. En 2010 j’ai décidé de réécrire l’histoire de Claudio, en français. Pascale Binamé a relu, recopié et complété le palmarès de Claudio que j’avais établi sur la base de ses écrits et qui avait été corrigé par de nombreux amis parmi lesquels, principalement, Almo Giambisi, Alberto Dorigatti et Heinz Steinkötter. Les voies parcourues dans les falaises comme Freyr sont trop nombreuses, mais il est intéressant de connaître les séjours de Claudio dans des sites comme Fontainebleau, le Saussois, les Calanques ou autres. Il est probable que le palmarès actuel ne soit pas complet. Les personnes qui noteraient des erreurs ou pourraient apporter d’autres précisions peuvent les envoyer à Didier Demeter via le site. Anne 1953 Massif de la Vanoise – Savoie (France) 21 VII 53 Dôme et Aiguille de Polset avec un Guide de Pralognan et un Parisien en troisième. 4h25 – 11h30: montée 5h, descente 2h. 1954 ( Lacedelli e Compagnoni al K2 ) Alpes bernoises (Suisse) 23 VII 54 Gspaltenhorn Voie normale avec le Guide Alfred Stäger de Mürren et Steiner de Lausanne en second. -

The Modernisation of Elite British Mountaineering

The Modernisation of Elite British Mountaineering: Entrepreneurship, Commercialisation and the Career Climber, 1953-2000 Thomas P. Barcham Thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of De Montfort University for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Submission date: March 2018 Contents Abstract ................................................................................................................................................... 4 Acknowledgments ................................................................................................................................... 5 Table of Abbreviations and Acronyms .................................................................................................... 6 Table of Figures ....................................................................................................................................... 7 Chapter 1. Introduction .......................................................................................................................... 8 Literature Review ............................................................................................................................ 14 Definitions, Methodology and Structure ........................................................................................ 29 Chapter 2. 1953 to 1969 - Breaking a New Trail: The Early Search for Earnings in a Fast Changing Pursuit ..................................................................................................................................................