'The Past Is a Foreign Country . . .'

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PV 1967 04.Pdf

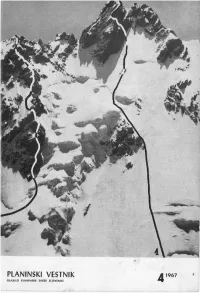

poštnina plačana v gotovini VSEBINA: RAZMIŠLJANJA OB NAŠIH ODPRAVAH V KAVKAZ Ing. Pavle Šegula 145 KAVKAZ - MOST MED ALPAMI IN HIMALAJO EMO Janez Krušic 149 SLOVENSKO REBRO V SEVERNI STENI GESTOLE Celje Janez Krušic 157 SLOVENSKI STEBER V ULLU-AUSU Ing. Drago Zagorc 160 TIMOFEJEVA SMER V MIŽIRGIJU EMAJLIRNICA Janez Golob 161 METALNA INDUSTRIJA KAKO SE JE CVET SLOVENSKIH ALPINISTOV PRIVAJAL NA VIŠINO 5145 METROV ORODJARNA Boris Krivic 164 NJEGOV ZADNJI VZPON A. Kopinšek 168 IZDELUJE IN DOBAVLJA: K DISKUSIJI O NEKATERIH KRAŠKIH OBLIKAH VISO- KOGORSKEGA KRASA — frite z dodatki za izdelavo emajlov Dušan Novak 169 — emajlirano, pocinkano in alu posodo, sanitarno SEDEM DESETLETIJ PLANINSKEGA VESTNIKA in gospodinjsko opremo ter kovinsko embalažo (1895-1965) — toplotne naprave: radiatorje in kotle za cen- Evgen Lovšin 174 tralno in etažno ogrevanje GOZD JE NAŠ DOM 180 — odpreske in kolesa za motorna vozila ter od- DRUŠTVENE NOVICE 183 preske za rudarstvo ALPINISTIČNE NOVICE 184 — vse vrste orodij zo serijsko proizvodnjo: rezilna, IZ PLANINSKE LITERATURE 187 izsekovalna, vlečna, kombinirana in upogibna RAZGLED PO SVETU 188 orodja za predelavo pločevine, orodja za tlačni ANICA KUK liv in za proizvodnjo iz plastičnih mas, stekla Stanislav Gilič 191 in keramike NASLOVNA STRAN: — emajlira, pocinkuje in predeluje pločevine SEVERNO OSTENJE ULLU-AUS (4789 m) 1 - DIREKTNA SMER V SEVERNI STENI Tel.: 39-21 - Telegram: EMO-Celje - Telex: 0335-12 2 - SLOVENSKI STEBER - PRVENSTVENA SMER SEDEŽ: LJUBLJANA - VEVČE USTANOVLJENE LETA 1842 IZDELUJEJO SULFITNO CELULOZO I. a za vse vrste papirja PINOTAN - strojilni ekstrat BREZLESNI PAPIR za grafično in predelovalno in- dustrijo: za reprezentativne izdaje, umetniške slike, propagandne in turistične prospekte, za pisemski papir in kuverte najboljše kvalitete, za razne protokole, matične knjige, obrazce, -Planinski Vestnik« je glasilo Planinske zveze Slovenije / šolske zvezke in podobno Izdaja ga PZS - urejuje ga uredniški odbor. -

Journal 45 Autumn 2008

JOHN MUIR TRUST October 2008 No 45 Biodiversity: helping nature heal itself Saving energy: saving wild land Scotland’s missing lynx ADVERT 2 John Muir Trust Journal 45, October 2008 JOHN MUIR TRUST October 2008 No 45 Contents Nigel’s notes Foreword from the Chief Executive of the John Muir Trust, 3 The return of the natives: Nigel Hawkins Members air their views devotees – all those people who on re-introductions care passionately about wild land and believe in what the Trust is 5 Stained glass trying to do. commemorates John Muir During those 25 years there has been a constant process Bringing back trees to of change as people become 6 involved at different stages of our the Scottish Borders development and then move on, having made their mark in all 8 Biodiversity: sorts of different ways. Helping nature heal itself The John Muir Trust has We are going through another constantly seen change as period of change at the John Muir 11 Scotland’s missing lynx it develops and grows as Trust as two of us who have been the country’s leading wild very involved in the Trust and in land organisation. taking it forward, step down. In 12 Leave No Trace: the process, opportunities are created for new people to become Cleaning up the wilds Change is brought about by involved and to bring in their own what is happening in society, energy, freshness, experience, Inspiration Point the economy and in the political 13 skills and passion for our cause. world, with the Trust responding We can be very confident – based to all of these. -

Amanita Nivalis

Lost and Found Fungi Datasheet Amanita nivalis WHAT TO LOOK FOR? A white to greyish to pale grey/yellow-brown mushroom, cap 4 to 8 cm diameter, growing in association with the creeping Salix herbacea (“dwarf willow” or “least willow”), on mountain peaks and plateaus at altitudes of ~700+ m. Distinctive field characters include the presence of a volva (sac) at the base; a cylindrical stalk lacking a ring (although sometimes an ephemeral ring can be present); white to cream gills; striations on the cap margin to 1/3 of the radius; and sometimes remnants of a white veil still attached on the top of the cap. WHEN TO LOOK? Amanita nivalis, images © D.A. Evans In GB from August to late September, very rarely in July or October. WHERE TO LOOK? Mountain summits, and upland and montane heaths, where Salix herbacea is present (see here for the NBN distribution map of S. herbacea). A moderate number of sites are known, mostly in Scotland, but also seven sites in England in the Lake District, and four sites in Snowdonia, Wales. Many Scottish sites have not been revisited in recent years, and nearby suitable habitats may not have been investigated. Further suitable habitats could be present in mountain regions throughout Scotland; the Lake District, Pennines and Yorkshire Dales in England; and Snowdonia and the Brecon Beacons in Wales. Amanita nivalis, with Salix herbacea visible in the foreground. Image © E.M. Holden Salix herbacea – known distribution Amanita nivalis – known distribution Map Map dataMap data © National Biodiversity Network 2015 Network Biodiversity National © © 2015 GeoBasis - DE/BKG DE/BKG ( © 2009 ), ), Google Pre-1965 1965-2015 Pre-1965 1965-2014 During LAFF project Amanita nivalis Associations General description Almost always found with Salix herbacea. -

Layout 1 Copy

STACK ROCK 2020 An illustrated guide to sea stack climbing in the UK & Ireland - Old Harry - - Old Man of Stoer - - Am Buachaille - - The Maiden - - The Old Man of Hoy - - over 200 more - Edition I - version 1 - 13th March 1994. Web Edition - version 1 - December 1996. Web Edition - version 2 - January 1998. Edition 2 - version 3 - January 2002. Edition 3 - version 1 - May 2019. Edition 4 - version 1 - January 2020. Compiler Chris Mellor, 4 Barnfield Avenue, Shirley, Croydon, Surrey, CR0 8SE. Tel: 0208 662 1176 – E-mail: [email protected]. Send in amendments, corrections and queries by e-mail. ISBN - 1-899098-05-4 Acknowledgements Denis Crampton for enduring several discussions in which the concept of this book was developed. Also Duncan Hornby for information on Dorset’s Old Harry stacks and Mick Fowler for much help with some of his southern and northern stack attacks. Mike Vetterlein contributed indirectly as have Rick Cummins of Rock Addiction, Rab Anderson and Bruce Kerr. Andy Long from Lerwick, Shetland. has contributed directly with a lot of the hard information about Shetland. Thanks are also due to Margaret of the Alpine Club library for assistance in looking up old journals. In late 1996 Ben Linton, Ed Lynch-Bell and Ian Brodrick undertook the mammoth scanning and OCR exercise needed to transfer the paper text back into computer form after the original electronic version was lost in a disk crash. This was done in order to create a world-wide web version of the guide. Mike Caine of the Manx Fell and Rock Club then helped with route information from his Manx climbing web site. -

Pinnacle Club Jubilee Journal 1921-1971

© Pinnacle Club and Author All Rights Reserved PINNACLE CLUB JUBILEE JOURNAL 1921-1971 © Pinnacle Club and Author All Rights Reserved THE PINNACLE CLUB JOURNAL Fiftieth Anniversary Edition Published Edited by Gill Fuller No. 14 1969——70 © Pinnacle Club and Author All Rights Reserved THE PINNACLE CLUB OFFICERS AND COMMITTEE 1971 1921-1971 President: MRS. JANET ROGERS 8 The Penlee, Windsor Terrace, Penarth, Glamorganshire Vice-President: Miss MARGARET DARVALL The Coach House, Lyndhurst Terrace, London N.W.3 (Tel. 01-794 7133) Hon. Secretary: MRS. PAT DALEY 73 Selby Lane, Keyworth, Nottingham (Tel. 060-77 3334) Hon. Treasurer: MRS. ADA SHAW 25 Crowther Close, Beverley, Yorkshire (Tel. 0482 883826) Hon. Meets Secretary: Miss ANGELA FALLER 101 Woodland Hill, Whitkirk, Leeds 15 (Tel. 0532 648270) Hon Librarian: Miss BARBARA SPARK Highfield, College Road, Bangor, North Wales (Tel. Bangor 3330) Hon. Editor: Mrs. GILL FULLER Dog Bottom, Lee Mill Road, Hebden Bridge, Yorkshire. Hon. Business Editor: Miss ANGELA KELLY 27 The Avenue, Muswell Hill, London N.10 (Tel. 01-883 9245) Hon. Hut Secretary: MRS. EVELYN LEECH Ty Gelan, Llansadwrn, Anglesey, (Tel. Beaumaris 287) Hon. Assistant Hut Secretary: Miss PEGGY WILD Plas Gwynant Adventure School, Nant Gwynant, Caernarvonshire (Tel.Beddgelert212) Committee: Miss S. CRISPIN Miss G. MOFFAT MRS. S ANGELL MRS. J. TAYLOR MRS. N. MORIN Hon. Auditor: Miss ANNETTE WILSON © Pinnacle Club and Author All Rights Reserved CONTENTS Page Our Fiftieth Birthday ...... ...... Dorothy Pilley Richards 5 Wheel Full Circle ...... ...... Gwen M offat ...... 8 Climbing in the A.C.T. ...... Kath Hoskins ...... 14 The Early Days ..... ...... ...... Trilby Wells ...... 17 The Other Side of the Circus .... -

Download Report for Winter Season 2011/2012

SPORTSCOTLAND AVALANCHE INFORMATION SERVICE REPORT FOR WINTER 2011/12 Avalanche Feith Bhuidhe - Northern Cairngorms. photo I Peter Mark Diggins - Co-ordinator October 2012 Glenmore Lodge, Aviemore, Inverness-shire PH22 1PU • telephone:+441479 861264 • www.sais.gov.uk Table of Contents The General Snowpack Situation - Winter 2011/12! 1 SAIS Operation! 2 Personnel! 2 The SAIS team,! 2 Avalanche Hazard Information Reports! 3 Avalanche Occurrences! 4 Recorded Avalanche Occurrences for the Winter of 2011/12! 4 Reaching the Public! 5 New Mobile Phone Site! 5 Report Boards in Public Places! 5 Avalanche Reports by Text! 5 The Website! 6 Chart 2 illustrating Website Activity! 6 Numbers viewing the daily SAIS Avalanche Forecast Reports.! 6 SAIS Blog Activity! 6 Working with Agencies and Groups! 7 Snow and Avalanche Foundation Of Scotland! 7 Research and Development! 7 The University of Edinburgh! 7 Snow and Ice Mechanics! 7 Snow, Ice and Avalanche Applications (SNAPS)! 8 Scottish Mountain Snow Research! 8 Seminars! 9 European Avalanche Warning Service International Snow Science Workshop! 9 Mountaineering Organisations! 9 Other Agencies and Groups! 10 SEPA and the MET OFFICE! 10 MET OFFICE and SAIS developments! 10 SAIS/Snowsport Scotland Freeride initiative! 11 Support and Sponsorship! 11 ! 2 The General Snowpack Situation - Winter 2011/12 Braeriach and Ben Macdui from Glas Maol in Feb The SAIS winter season started early in December 2011 with a weekend report service being provided in the Northern Cairngorms and Lochaber areas. The first winter storms arrived late October at summit levels, with natural avalanche activity reported on Ben Wyvis, then more significant snowfall later in November. -

Mountaineering War and Peace at High Altitudes

Mountaineering War and Peace at High Altitudes 2–5 Sackville Street Piccadilly London W1S 3DP +44 (0)20 7439 6151 [email protected] https://sotherans.co.uk Mountaineering 1. ABBOT, Philip Stanley. Addresses at a Memorial Meeting of the Appalachian Mountain Club, October 21, 1896, and other 2. ALPINE SLIDES. A Collection of 72 Black and White Alpine papers. Reprinted from “Appalachia”, [Boston, Mass.], n.d. [1896]. £98 Slides. 1894 - 1901. £750 8vo. Original printed wrappers; pp. [iii], 82; portrait frontispiece, A collection of 72 slides 80 x 80mm, showing Alpine scenes. A 10 other plates; spine with wear, wrappers toned, a good copy. couple with cracks otherwise generally in very good condition. First edition. This is a memorial volume for Abbot, who died on 44 of the slides have no captioning. The remaining are variously Mount Lefroy in August 1896. The booklet prints Charles E. Fay’s captioned with initials, “CY”, “EY”, “LSY” AND “RY”. account of Abbot’s final climb, a biographical note about Abbot Places mentioned include Morteratsch Glacier, Gussfeldt Saddle, by George Herbert Palmer, and then reprints three of Abbot’s Mourain Roseg, Pers Ice Falls, Pontresina. Other comments articles (‘The First Ascent of Mount Hector’, ‘An Ascent of the include “Big lunch party”, “Swiss Glacier Scene No. 10” Weisshorn’, and ‘Three Days on the Zinal Grat’). additionally captioned by hand “Caution needed”. Not in the Alpine Club Library Catalogue 1982, Neate or Perret. The remaining slides show climbing parties in the Alps, including images of lady climbers. A fascinating, thus far unattributed, collection of Alpine climbing. -

The Story of Creag Meagaidh National Nature Reserve

Scotland’s National Nature Reserves For more information about Creag Meagaidh National Nature Reserve please contact: Scottish Natural Heritage, Creag Meagaidh NNR, Aberarder, Kinlochlaggan, Newtonmore, Inverness-shire, PH20 1BX Telephone/Fax: 01528 544 265 Email: [email protected] The Story of Creag Meagaidh National Nature Reserve The Story of Creag Meagaidh National Nature Reserve Foreword Creag Meagaidh National Nature Reserve (NNR), named after the great whalebacked ridge which dominates the Reserve, is one of the most diverse and important upland sites in Scotland. Creag Meagaidh is a complex massif, with numerous mountain tops and an extensive high summit plateau edged by a dramatic series of ice-carved corries and gullies. The Reserve extends from the highest of the mountain tops to the shores of Loch Laggan. The plateau is carpeted in moss-heath and is an important breeding ground for dotterel. The corries support unusual artic- alpine plants and the lower slopes have scattered patches of ancient woodland dominated by birch. Located 45 kilometres (km) northeast of Fort William and covering nearly 4,000 hectares (ha), the Reserve is owned and managed by Scottish Natural Heritage (SNH). Creag Meagaidh has been a NNR since 1986 and during the last twenty years SNH has worked to restore natural habitats, particularly woodland, on the Reserve. Like much of the Highlands, the vegetation has been heavily grazed for centuries, so it was decided to reduce the number of grazing animals by removing sheep and culling red deer. The aim was not to eliminate grazing animals altogether, but to keep numbers at a level that allowed the habitats, especially the woodland, to recover. -

Scottish Highlands Hillwalking

SHHG-3 back cover-Q8__- 15/12/16 9:08 AM Page 1 TRAILBLAZER Scottish Highlands Hillwalking 60 DAY-WALKS – INCLUDES 90 DETAILED TRAIL MAPS – INCLUDES 90 DETAILED 60 DAY-WALKS 3 ScottishScottish HighlandsHighlands EDN ‘...the Trailblazer series stands head, shoulders, waist and ankles above the rest. They are particularly strong on mapping...’ HillwalkingHillwalking THE SUNDAY TIMES Scotland’s Highlands and Islands contain some of the GUIDEGUIDE finest mountain scenery in Europe and by far the best way to experience it is on foot 60 day-walks – includes 90 detailed trail maps o John PLANNING – PLACES TO STAY – PLACES TO EAT 60 day-walks – for all abilities. Graded Stornoway Durness O’Groats for difficulty, terrain and strenuousness. Selected from every corner of the region Kinlochewe JIMJIM MANTHORPEMANTHORPE and ranging from well-known peaks such Portree Inverness Grimsay as Ben Nevis and Cairn Gorm to lesser- Aberdeen Fort known hills such as Suilven and Clisham. William Braemar PitlochryPitlochry o 2-day and 3-day treks – some of the Glencoe Bridge Dundee walks have been linked to form multi-day 0 40km of Orchy 0 25 miles treks such as the Great Traverse. GlasgowGla sgow EDINBURGH o 90 walking maps with unique map- Ayr ping features – walking times, directions, tricky junctions, places to stay, places to 60 day-walks eat, points of interest. These are not gen- for all abilities. eral-purpose maps but fully edited maps Graded for difficulty, drawn by walkers for walkers. terrain and o Detailed public transport information strenuousness o 62 gateway towns and villages 90 walking maps Much more than just a walking guide, this book includes guides to 62 gateway towns 62 guides and villages: what to see, where to eat, to gateway towns where to stay; pubs, hotels, B&Bs, camp- sites, bunkhouses, bothies, hostels. -

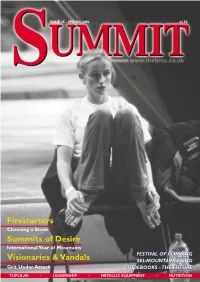

Firestarters Summits of Desire Visionaries & Vandals

31465_Cover 12/2/02 9:59 am Page 2 ISSUE 25 - SPRING 2002 £2.50 Firestarters Choosing a Stove Summits of Desire International Year of Mountains FESTIVAL OF CLIMBING Visionaries & Vandals SKI-MOUNTAINEERING Grit Under Attack GUIDEBOOKS - THE FUTURE TUPLILAK • LEADERSHIP • METALLIC EQUIPMENT • NUTRITION FOREWORD... NEW SUMMITS s the new BMC Chief Officer, writing my first ever Summit Aforeword has been a strangely traumatic experience. After 5 years as BMC Access Officer - suddenly my head is on the block. Do I set out my vision for the future of the BMC or comment on the changing face of British climbing? Do I talk about the threats to the cliff and mountain envi- ronment and the challenges of new access legislation? How about the lessons learnt from foot and mouth disease or September 11th and the recent four fold hike in climbing wall insurance premiums? Big issues I’m sure you’ll agree - but for this edition I going to keep it simple and say a few words about the single most important thing which makes the BMC tick - volunteer involvement. Dave Turnbull - The new BMC Chief Officer Since its establishment in 1944 the BMC has relied heavily on volunteers and today the skills, experience and enthusi- District meetings spearheaded by John Horscroft and team asm that the many 100s of volunteers contribute to climb- are pointing the way forward on this front. These have turned ing and hill walking in the UK is immense. For years, stal- into real social occasions with lively debates on everything warts in the BMC’s guidebook team has churned out quality from bolts to birds, with attendances of up to 60 people guidebooks such as Chatsworth and On Peak Rock and the and lively slideshows to round off the evenings - long may BMC is firmly committed to getting this important Commit- they continue. -

CC J Inners 168Pp.Indd

theclimbers’club Journal 2011 theclimbers’club Journal 2011 Contents ALPS AND THE HIMALAYA THE HOME FRONT Shelter from the Storm. By Dick Turnbull P.10 A Midwinter Night’s Dream. By Geoff Bennett P.90 Pensioner’s Alpine Holiday. By Colin Beechey P.16 Further Certifi cation. By Nick Hinchliffe P.96 Himalayan Extreme for Beginners. By Dave Turnbull P.23 Welsh Fix. By Sarah Clough P.100 No Blends! By Dick Isherwood P.28 One Flew Over the Bilberry Ledge. By Martin Whitaker P.105 Whatever Happened to? By Nick Bullock P.108 A Winter Day at Harrison’s. By Steve Dean P.112 PEOPLE Climbing with Brasher. By George Band P.36 FAR HORIZONS The Dragon of Carnmore. By Dave Atkinson P.42 Climbing With Strangers. By Brian Wilkinson P.48 Trekking in the Simien Mountains. By Rya Tibawi P.120 Climbing Infl uences and Characters. By James McHaffi e P.53 Spitkoppe - an Old Climber’s Dream. By Ian Howell P.128 Joe Brown at Eighty. By John Cleare P.60 Madagascar - an African Yosemite. By Pete O’Donovan P.134 Rock Climbing around St Catherine’s Monastery in the Sinai Desert. By Malcolm Phelps P.142 FIRST ASCENTS Summer Shale in Cornwall. By Mick Fowler P.68 OBITUARIES A Desert Nirvana. By Paul Ross P.74 The First Ascent of Vector. By Claude Davies P.78 George Band OBE. 1929 - 2011 P.150 Three Rescues and a Late Dinner. By Tony Moulam P.82 Alan Blackshaw OBE. 1933 - 2011 P.154 Ben Wintringham. 1947 - 2011 P.158 Chris Astill. -

1976 Bicentennial Mckinley South Buttress Expedition

THE MOUNTAINEER • Cover:Mowich Glacier Art Wolfe The Mountaineer EDITORIAL COMMITTEE Verna Ness, Editor; Herb Belanger, Don Brooks, Garth Ferber. Trudi Ferber, Bill French, Jr., Christa Lewis, Mariann Schmitt, Paul Seeman, Loretta Slater, Roseanne Stukel, Mary Jane Ware. Writing, graphics and photographs should be submitted to the Annual Editor, The Mountaineer, at the address below, before January 15, 1978 for consideration. Photographs should be black and white prints, at least 5 x 7 inches, with caption and photo grapher's name on back. Manuscripts should be typed double· spaced, with at least 1 Y:z inch margins, and include writer's name, address and phone number. Graphics should have caption and artist's name on back. Manuscripts cannot be returned. Properly identified photographs and graphics will be returnedabout June. Copyright © 1977, The Mountaineers. Entered as second·class matter April8, 1922, at Post Office, Seattle, Washington, under the act of March 3, 1879. Published monthly, except July, when semi-monthly, by The Mountaineers, 719 Pike Street,Seattle, Washington 98101. Subscription price, monthly bulletin and annual, $6.00 per year. ISBN 0-916890-52-X 2 THE MOUNTAINEERS PURPOSES To explore and study the mountains, forests, and watercourses of the Northwest; To gather into permanentform the history and tra ditions of thisregion; To preserve by the encouragement of protective legislation or otherwise the natural beauty of NorthwestAmerica; To make expeditions into these regions in fulfill ment of the above purposes; To encourage a spirit of good fellowship among all loversof outdoor life. 0 � . �·' ' :···_I·:_ Red Heather ' J BJ. Packard 3 The Mountaineer At FerryBasin B.