A Pastoral Study

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Form Social Prophets to Soc Princ 1890-1990-K Rowe

UMHistory/Prof. Rowe/ Social Prophets revised November 29, 2009 FROM SOCIAL PROPHETS TO SOCIAL PRINCIPLES 1890s-1990s Two schools of social thought have been at work, sometimes at war, in UM History 1) the Pietist ―stick to your knitting‖ school which focuses on gathering souls into God’s kingdom and 2) the activist ―we have a broader agenda‖ school which is motivated to help society reform itself. This lecture seeks to document the shift from an ―old social agenda,‖ which emphasized sabbath observance, abstinence from alcohol and ―worldly amusements‖ to a ―new agenda‖ that overlaps a good deal with that of progressives on the political left. O u t l i n e 2 Part One: A CHANGE OF HEART in late Victorian America (1890s) 3 Eight Prophets cry in the wilderness of Methodist Pietism Frances Willard, William Carwardine, Mary McDowell, S. Parkes Cadman, Edgar J. Helms, William Bell, Ida Tarbell and Frank Mason North 10 Two Social Prophets from other Christian traditions make the same pitch at the same time— that one can be a dedicated Christian and a social reformer at the same time: Pope Leo XIII and Walter Rauschenbusch. 11 Part Two: From SOCIAL GOSPEL to SOCIAL CHURCH 1900-1916 12 Formation of the Methodist Federation for Social Service, 1907 16 MFSS presents first Social Creed to MEC General Conference, 1908 18 Toward a ―Socialized‖ Church? 1908-1916 21 The Social Gospel: Many Limitations / Impressive Legacy Part Three: SOCIAL GOSPEL RADICALISM & RETREAT TO PIETISM 1916-1960 22 Back to Abstinence and forward to Prohibition 1910s 24 Methodism -

Front Matter

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-41607-8 - Self and Salvation: Being Transformed David F. Ford Frontmatter More information Self and Salvation Being Transformed This eagerly awaited book by David F.Ford makes a unique and important contribution to the debate about the Christian doctrine of salvation. Using the pivotal image of the face, Professor Ford offers a constructive and contemporary account of the self being transformed. He engages with three modern thinkers (Levinas, Jüngel and Ricoeur) in order to rethink and reimagine the meaning of self. Developing the concept of a worshipping self, he goes on to explore the dimensions of salvation through the lenses of scripture, worship practices, the life, death and resurrection of Jesus Christ, and the lives of contemporary saints. He uses different genres and traditions to show how the self flourishes through engagement with God, other people, and the responsibilities and joys of ordinary living. The result is a habitable theology of salvation which is immersed in Christian faith, thought and practice while also being deeply involved with modern life in a pluralist world. David F.Ford is Regius Professor of Divinity in the University of Cambridge, where he is also a Fellow of Selwyn College and Chairman of the Centre for Advanced Religious and Theological Studies. Educated at Trinity College Dublin, St John’s College Cambridge, YaleUniversity and Tübingen University,he has taught previously at the University of Birmingham. Professor Ford’s publications include Barth and God’s Story: Biblical Narrative and the Theological Method of Karl Barth in the Church Dogmatics (1981), Jubilate: Theology in Praise (with Daniel W.Hardy,1984), Meaning and Truth in 2 Corinthians (with F.M. -

NTOZAKE SHANGE, JAMILA WOODS, and NITTY SCOTT by Rachel O

THEORIZING BLACK WOMANHOOD IN ART: NTOZAKE SHANGE, JAMILA WOODS, AND NITTY SCOTT by Rachel O. Smith A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of Purdue University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Department of English West Lafayette, Indiana May 2020 THE PURDUE UNIVERSITY GRADUATE SCHOOL STATEMENT OF COMMITTEE APPROVAL Dr. Marlo David, Chair Department of English Dr. Aparajita Sagar Department of English Dr. Paul Ryan Schneider Department of English Approved by: Dr. Dorsey Armstrong 2 This thesis is dedicated to my mother, Carol Jirik, who may not always understand why I do this work, but who supports me and loves me unconditionally anyway. 3 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to first thank Dr. Marlo David for her guidance and validation throughout this process. Her feedback has pushed me to investigate these ideas with more clarity and direction than I initially thought possible, and her mentorship throughout this first step in my graduate career has been invaluable. I would also like to thank the other members of my committee, Dr. Aparajita Sagar and Dr. Ryan Schneider, for helping me polish this piece of writing and for supporting me throughout this two-year program as I prepared to write this by participating in their seminars and working with them to prepare conference materials. Without these three individuals I would not have the confidence that I now have to continue on in my academic career. Additionally, I would like to thank my friends in the English Department at Purdue University and my friends back home in Minnesota who listened to my jumbled thoughts about popular culture and Black womanhood and asked me challenging questions that helped me to shape the argument that appears in this document. -

Jean Lee in the Repulsion Felt by Some of Them D.Min to the "Foreign and Erotic Iconography of the Church."20 Dr

CJET: T&T/JAMAICA FIFTIETH ANNNIVERSARY EDITION In his dissertation entitled Understanding Male Absence from MEN, THE the Jamaican Church, Dr. Sam FAMILY, AND V assel explores and addresses the problem ofthe low ratio of men as THE CHURCH: compared to women in the Church. He concludes that the reasons for A .JAMAICA this are to be located in the TESTAMENT perception commonly held by men By that "the Church in Jamaica is . ... 'womanish' and 'childish"', and Jean Lee in the repulsion felt by some of them D.Min to the "foreign and erotic iconography of the Church."20 Dr. Lee is full Lecturer Vassel's conclusions are based on "empirical observation among men at the Jamaica Theology 21 Seminary and former in Jamaica" (which includes a case missionary to the study of the local church where he Dominican Republic was pastor at the time of the 20See Samuel Carl W. V assel,. Understanding and Addressing Male Absence From the Jamaican Church (Doctoral Dissertation, Colombia Theological Seminary/United Theological College, Doctor ofMinistry, 1997). Subsequently published in booklet form by Sam Vassel Ministries. Undated) Abstract, ii. This and any subsequent reference are from the booklet, not the original dissertation. · 21 Ibid. p. 2. 40 CJET: T&T/JAMAICA FIFTIETH ANNNIVERSARY EDITION investigation) and enhanced by statistical data about men's involvement as compared with women's, across various denominations in Jamaica. Vassel proposes a revamping of the culturally bound Christology informing the kind of evangelism practised by colonial and neo-colonial bearers of the Gospel message, and which has · proven inadequate to connect with and, therefore, transform the vast majority of our Caribbean and, in particular, our Jamaican males. -

Black Religion and Aesthetics Contributors

Black Religion and Aesthetics Contributors ROBERT BECKFORD is Reader in Black Theology and Culture at Oxford Brookes University (UK) and a Documentary Presenter for BBC and Channel 4 (United Kingdom). ELIAS K. BONGMBA is Professor of Religious Studies at Rice University, Houston, Texas. MIGUEL A. DE LA TORRE is Associate Professor of Social Ethics and Director of the Justice and Peace Institute at Iliff School of Theology, Denver, Colorado. CAROL B. DUNCAN is Associate Professor and Chair of the Department of Religion and Culture at Wilfrid Laurier University, Waterloo, Canada. LINDSAY L. HALE is a Lecturer in Anthropology at the University of Texas at Austin. LIZABETH PARAVISINI-GEBERT is Professor of Hispanic Studies on the Randolph Distinguished Professor Chair and Director of Africana Studies at Vassar College. ANTHONY B. PINN is Agnes Cullen Arnold Professor of Humanities and Professor of Religious Studies at Rice University, Houston, Texas. ANTHONY G. REDDIE is Research Fellow and Consultant in Black Theological Studies for the Queen’s Foundation for Ecumenical Theological Education in Birmingham (United Kingdom). LINDA E. THOMAS is Professor of Theology and Anthropology at Lutheran School of Theology, Chicago, Illinois. NANCY LYNNE WESTFIELD is Associate Professor of Religious Education with a joint appointment at the Theological Seminary and Graduate School of Drew University, Madison, New Jersey. Black Religion and Aesthetics Religious Thought and Life in Africa and the African Diaspora Edited by Anthony B. Pinn BLACK RELIGION AND AESTHETICS Copyright © Anthony B. Pinn, 2009. Softcover reprint of the hardcover 1st edition 2009 978-0-230-60550-3 All rights reserved. First published in 2009 by PALGRAVE MACMILLAN® in the United States—a division of St. -

The Incorporation of an Individual Into the Liturgical Action of the Church of England

Durham E-Theses The incorporation of an individual into the liturgical action of the church of England Dewes, Deborah How to cite: Dewes, Deborah (1996) The incorporation of an individual into the liturgical action of the church of England, Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/5245/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk 2 The Incorporation of an Individual into the Liturgical Action of the Church of England The copyright of this thesis rests with the author. No quotation from it should be published without his prior written consent and information derived from it should be acknowledged. M.A.Thesis submitted by Rev'd Deborah Dewes University of Durham Theology Faculty 1995 2 0 JUNTO I confirm that no part of the material offered has previously been submitted by me for a degree in this or any other university Signed. -

Song Catalogue February 2020 Artist Title 2 States Mast Magan 2 States Locha E Ulfat 2 Unlimited No Limit 2Pac Dear Mama 2Pac Changes 2Pac & Notorious B.I.G

Song Catalogue February 2020 Artist Title 2 States Mast Magan 2 States Locha_E_Ulfat 2 Unlimited No Limit 2Pac Dear Mama 2Pac Changes 2Pac & Notorious B.I.G. Runnin' (Trying To Live) 2Pac Feat. Dr. Dre California Love 3 Doors Down Kryptonite 3Oh!3 Feat. Katy Perry Starstrukk 3T Anything 4 Non Blondes What's Up 5 Seconds of Summer Youngblood 5 Seconds of Summer She's Kinda Hot 5 Seconds of Summer She Looks So Perfect 5 Seconds of Summer Hey Everybody 5 Seconds of Summer Good Girls 5 Seconds of Summer Girls Talk Boys 5 Seconds of Summer Don't Stop 5 Seconds of Summer Amnesia 5 Seconds of Summer (Feat. Julia Michaels) Lie to Me 5ive When The Lights Go Out 5ive We Will Rock You 5ive Let's Dance 5ive Keep On Movin' 5ive If Ya Getting Down 5ive Got The Feelin' 5ive Everybody Get Up 6LACK Feat. J Cole Pretty Little Fears 7Б Молодые ветра 10cc The Things We Do For Love 10cc Rubber Bullets 10cc I'm Not In Love 10cc I'm Mandy Fly Me 10cc Dreadlock Holiday 10cc Donna 30 Seconds To Mars The Kill 30 Seconds To Mars Rescue Me 30 Seconds To Mars Kings And Queens 30 Seconds To Mars From Yesterday 50 Cent Just A Lil Bit 50 Cent In Da Club 50 Cent Candy Shop 50 Cent Feat. Eminem & Adam Levine My Life 50 Cent Feat. Snoop Dogg and Young Jeezy Major Distribution 101 Dalmatians (Disney) Cruella De Vil 883 Nord Sud Ovest Est 911 A Little Bit More 1910 Fruitgum Company Simon Says 1927 If I Could "Weird Al" Yankovic Men In Brown "Weird Al" Yankovic Ebay "Weird Al" Yankovic Canadian Idiot A Bugs Life The Time Of Your Life A Chorus Line (Musical) What I Did For Love A Chorus Line (Musical) One A Chorus Line (Musical) Nothing A Goofy Movie After Today A Great Big World Feat. -

Amos Yong Complete Curriculum Vitae

Y o n g C V | 1 AMOS YONG COMPLETE CURRICULUM VITAE Table of Contents PERSONAL & PROFESSIONAL DATA ..................................................................................... 2 Education ................................................................................................................................................... 2 Academic & Administrative Positions & Other Employment .................................................................... 3 Visiting Professorships & Fellowships ....................................................................................................... 3 Memberships & Certifications ................................................................................................................... 3 PUBLICATIONS ............................................................................................................................ 4 Monographs/Books – and Reviews Thereof.............................................................................................. 4 Edited Volumes – and Reviews Thereof .................................................................................................. 11 Co-edited Book Series .............................................................................................................................. 16 Missiological Engagements: Church, Theology and Culture in Global Contexts (IVP Academic) – with Scott W. Sunquist and John R. Franke ................................................................................................ -

Parody and Pastiche

Evaluating the Impact of Parody on the Exploitation of Copyright Works: An Empirical Study of Music Video Content on YouTube Parody and Pastiche. Study I. January 2013 Kris Erickson This is an independent report commissioned by the Intellectual Property Office (IPO) Intellectual Property Office is an operating name of the Patent Office © Crown copyright 2013 2013/22 Dr. Kris Erickson is Senior Lecturer in Media Regulation at the Centre ISBN: 978-1-908908-63-6 for Excellence in Media Practice, Bournemouth University Evaluating the impact of parody on the exploitation of copyright works: An empirical study of music (www.cemp.ac.uk). E-mail: [email protected] video content on YouTube Published by The Intellectual Property Office This is the first in a sequence of three reports on Parody & Pastiche, 8th January 2013 commissioned to evaluate policy options in the implementation of the Hargreaves Review of Intellectual Property & Growth (2011). This study 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 presents new empirical data about music video parodies on the online © Crown Copyright 2013 platform YouTube; Study II offers a comparative legal review of the law of parody in seven jurisdictions; Study III provides a summary of the You may re-use this information (excluding logos) free of charge in any format or medium, under the findings of Studies I & II, and analyses their relevance for copyright terms of the Open Government Licence. To view policy. this licence, visit http://www.nationalarchives.gov. uk/doc/open-government-licence/ or email: [email protected] The author is grateful for input from Dr. -

Towards a Practical Theology for Effective Responses to Black Young Men Associated with Crime for Black Majority Churches

TOWARDS A PRACTICAL THEOLOGY FOR EFFECTIVE RESPONSES TO BLACK YOUNG MEN ASSOCIATED WITH CRIME FOR BLACK MAJORITY CHURCHES By Carver L. Anderson A thesis submitted to The University of Birmingham In fulfilment of the requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy School of Philosophy, Theology and Religion College of Arts and Law University of Birmingham February 2015 University of Birmingham Research Archive e-theses repository This unpublished thesis/dissertation is copyright of the author and/or third parties. The intellectual property rights of the author or third parties in respect of this work are as defined by The Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988 or as modified by any successor legislation. Any use made of information contained in this thesis/dissertation must be in accordance with that legislation and must be properly acknowledged. Further distribution or reproduction in any format is prohibited without the permission of the copyright holder. TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION 1 Background and Motivation 4 Theological Considerations 6 Fieldwork 10 Researcher’s Fieldwork Reflections 11 Outline of Thesis 13 CHAPTER ONE: THROUGH PRACTICAL THEOLOGICAL LENSES 17 1.1 Introduction 17 1.2 Inter-disciplinary Context 19 1.3 Entering the Practical Theological Arena 21 1.4 Practical Theology and Scriptural Considerations 26 1.5 Constructing a Framework for Doing Practical Theology 31 1.6 Towards the use of Personal Narratives in Practical Theology 34 1.7 Youth, Black Men and BMCs: A Hermeneutical Response 41 1.8 Conclusion 46 CHAPTER -

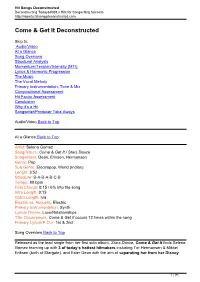

Come & Get It<Span Class="Orangetitle"> Deconstructed

Hit Songs Deconstructed Deconstructing Today's Hits for Songwriting Success http://reports.hitsongsdeconstructed.com Come & Get It Deconstructed Skip to: Audio/Video At a Glance Song Overview Structural Analysis Momentum/Tension/Intensity (MTI) Lyrics & Harmonic Progression The Music The Vocal Melody Primary Instrumentation, Tone & Mix Compositional Assessment Hit Factor Assessment Conclusion Why it’s a Hit Songwriter/Producer Take Aways Audio/Video Back to Top At a Glance Back to Top Artist: Selena Gomez Song/Album: Come & Get It / Stars Dance Songwriters: Dean, Eriksen, Hermansen Genre: Pop Sub Genre: Electropop, World (Indian) Length: 3:52 Structure: B-A-B-A-B-C-B Tempo: 80 bpm First Chorus: 0:15 / 6% into the song Intro Length: 0:15 Outro Length: n/a Electric vs. Acoustic: Electric Primary Instrumentation: Synth Lyrical Theme: Love/Relationships Title Occurrences: Come & Get It occurs 12 times within the song Primary Lyrical P.O.V: 1st & 2nd Song Overview Back to Top Released as the lead single from her first solo album, Stars Dance, Come & Get It finds Selena Gomez teaming up with 3 of today’s hottest hitmakers including Tor Hermansen & Mikkel Eriksen (both of Stargate), and Ester Dean with the aim of separating her from her Disney 1 / 71 Hit Songs Deconstructed Deconstructing Today's Hits for Songwriting Success http://reports.hitsongsdeconstructed.com past and to establish her as a major force within the mainstream Pop scene alongside contemporaries including Rihanna, Katy and Britney. As you’ll see within the report, Come & Get It possesses many of the “hit qualities” that are indicative of today’s chart-topping songs, but it also falls short in some key areas that preclude it from realizing its fullest potential. -

MTO 23.2: Lafrance, Finding Love in Hopeless Places

Finding Love in Hopeless Places: Complex Relationality and Impossible Heterosexuality in Popular Music Videos by Pink and Rihanna Marc Lafrance and Lori Burns KEYWORDS: Pink, Rihanna, music video, popular music, cross-domain analysis, relationality, heterosexuality, liquid love ABSTRACT: This paper presents an interpretive approach to music video analysis that engages with critical scholarship in the areas of popular music studies, gender studies and cultural studies. Two key examples—Pink’s pop video “Try” and Rihanna’s electropop video “We Found Love”—allow us to examine representations of complex human relationality and the paradoxical challenges of heterosexuality in late modernity. We explore Zygmunt Bauman’s notion of “liquid love” in connection with the selected videos. A model for the analysis of lyrics, music, and images according to cross-domain parameters ( thematic, spatial & temporal, relational, and gestural ) facilitates the interpretation of the expressive content we consider. Our model has the potential to be applied to musical texts from the full range of musical genres and to shed light on a variety of social and cultural contexts at both the micro and macro levels. Received December 2016 Volume 23, Number 2, June 2017 Copyright © 2017 Society for Music Theory [1.1] This paper presents and applies an analytic model for interpreting representations of gender, sexuality, and relationality in the words, music, and images of popular music videos. To illustrate the relevance of our approach, we have selected two songs by mainstream female artists who offer compelling reflections on the nature of heterosexual love and the challenges it poses for both men and women.