It's a Bird! It's a Plane!

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Daredevil by Frank Miller Box Set Ebook Free Download

DAREDEVIL BY FRANK MILLER BOX SET PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Frank Miller | 1896 pages | 15 Oct 2019 | Marvel Comics | 9781302919108 | English | New York, United States Daredevil By Frank Miller Box Set PDF Book Readers also enjoyed. Elektra 1 Items 1. This is the email address that you previously registered with on angusrobertson. Auction 1. Return to Book Page. Would you like us to keep your Bookworld order history? Again this run is famous for a reason and its definitely an enjoying collection. Dude really wa Despite being the companion piece to Frank Miller's Daredevil Omnibus, they actually put all the best stories in this one. I've never read a Miller book quite this abstract, Sienkiewicz art definitely helps but overall it didn't grab me too much. Seller does not offer returns. This story is brilliant, it shows kingpin at his worst, destroying daredevils life bit by bit. Hardcover , pages. El problema de los libros recopilatorios es que la variedad de artistas puede generar una muy amplia escala de calidad a lo largo de la obra. Delivery Options. Home Gardening International Subscriptions. Sign In Register. However, it's the writing that really sets it apart. Daredevil 7th Series Annual. Get A Copy. Daredevil 5th Series. Accept Close Privacy Policy. Canada Only. But we also get a long fight with Nuke and a comic that quickly becomes more about Captain America than Daredevil. The art is very strange. No No, I don't need my Bookworld details anymore. Average rating 4. Mirallegro rated it really liked it. This omni starts off with a 2 part story with spiderman in which spiderman becomes blind, so daredevil helps out. -

Batman Beyond 2.0: Marked Soul Volume 3 Free Download

BATMAN BEYOND 2.0: MARKED SOUL VOLUME 3 FREE DOWNLOAD Thony Silas,Phil Hester,Kyle Higgins | 176 pages | 22 Sep 2015 | DC Comics | 9781401258016 | English | United States BATMAN BEYOND 2.0 TP MARK OF THE PHANTASM VOL 03 After the evidence of the illegal weapon production is forcibly taken from Terry by Derek Powers, Terry subsequently steals the Batsuit, intending to bring Powers to justice. Retrieved October 23, A high-speed motorcycle chase between Terry and the Jokerz leads them to the grounds of Wayne Manor, where they run into the elderly Bruce Wayne. Barbara Gordon Robin. Later that night, Jim Tate aka Armory, one of Terry's old rogues, came home to find Hush along with his stepson and wife tied up. This is great! Green Lantern. Views Read Edit View history. Star Wars. Star Wars - Modern. Parasyte -the maxim. Silver Age. Bruce couldn't get close to Batman Beyond 2.0: Marked Soul Volume 3 because for some reason he wasn't on good terms with the police at that time. Terry and Melanie's relationship is similar to that of Bruce and Selina Kyle. Submit Back To Login. DC Universe. Download as PDF Printable version. She explains through flashbacks Batman Beyond 2.0: Marked Soul Volume 3, even though she grew to trust and respect Batman, she was aware of him aging, thus accepting the idea of either Bruce retiring or being killed at some point. Star Trek. Retrieved May 17, Terry returns home to discover that his father has been murdered, apparently by the vengeful Jokerz. -

Toys and Action Figures in Stock

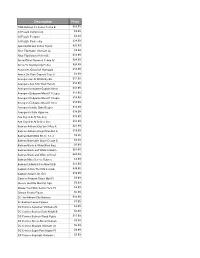

Description Price 1966 Batman Tv Series To the B $29.99 3d Puzzle Dump truck $9.99 3d Puzzle Penguin $4.49 3d Puzzle Pirate ship $24.99 Ajani Goldmane Action Figure $26.99 Alice Ttlg Hatter Vinimate (C: $4.99 Alice Ttlg Select Af Asst (C: $14.99 Arrow Oliver Queen & Totem Af $24.99 Arrow Tv Starling City Police $24.99 Assassins Creed S1 Hornigold $18.99 Attack On Titan Capsule Toys S $3.99 Avengers 6in Af W/Infinity Sto $12.99 Avengers Aou 12in Titan Hero C $14.99 Avengers Endgame Captain Ameri $34.99 Avengers Endgame Mea-011 Capta $14.99 Avengers Endgame Mea-011 Capta $14.99 Avengers Endgame Mea-011 Iron $14.99 Avengers Infinite Grim Reaper $14.99 Avengers Infinite Hyperion $14.99 Axe Cop 4-In Af Axe Cop $15.99 Axe Cop 4-In Af Dr Doo Doo $12.99 Batman Arkham City Ser 3 Ras A $21.99 Batman Arkham Knight Man Bat A $19.99 Batman Batmobile Kit (C: 1-1-3 $9.95 Batman Batmobile Super Dough D $8.99 Batman Black & White Blind Bag $5.99 Batman Black and White Af Batm $24.99 Batman Black and White Af Hush $24.99 Batman Mixed Loose Figures $3.99 Batman Unlimited 6-In New 52 B $23.99 Captain Action Thor Dlx Costum $39.95 Captain Action's Dr. Evil $19.99 Cartoon Network Titans Mini Fi $5.99 Classic Godzilla Mini Fig 24pc $5.99 Create Your Own Comic Hero Px $4.99 Creepy Freaks Figure $0.99 DC 4in Arkham City Batman $14.99 Dc Batman Loose Figures $7.99 DC Comics Aquaman Vinimate (C: $6.99 DC Comics Batman Dark Knight B $6.99 DC Comics Batman Wood Figure $11.99 DC Comics Green Arrow Vinimate $9.99 DC Comics Shazam Vinimate (C: $6.99 DC Comics Super -

Rambo: Last Blood Production Notes

RAMBO: LAST BLOOD PRODUCTION NOTES RAMBO: LAST BLOOD LIONSGATE Official Site: Rambo.movie Publicity Materials: https://www.lionsgatepublicity.com/theatrical/rambo-last-blood Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/Rambo/ Twitter: https://twitter.com/RamboMovie Instagram: https://www.instagram.com/rambomovie/ Hashtag: #Rambo Genre: Action Rating: R for strong graphic violence, grisly images, drug use and language U.S. Release Date: September 20, 2019 Running Time: 89 minutes Cast: Sylvester Stallone, Paz Vega, Sergio Peris-Mencheta, Adriana Barraza, Yvette Monreal, Genie Kim aka Yenah Han, Joaquin Cosio, and Oscar Jaenada Directed by: Adrian Grunberg Screenplay by: Matthew Cirulnick & Sylvester Stallone Story by: Dan Gordon and Sylvester Stallone Based on: The Character created by David Morrell Produced by: Avi Lerner, Kevin King Templeton, Yariv Lerner, Les Weldon SYNOPSIS: Almost four decades after he drew first blood, Sylvester Stallone is back as one of the greatest action heroes of all time, John Rambo. Now, Rambo must confront his past and unearth his ruthless combat skills to exact revenge in a final mission. A deadly journey of vengeance, RAMBO: LAST BLOOD marks the last chapter of the legendary series. Lionsgate presents, in association with Balboa Productions, Dadi Film (HK) Ltd. and Millennium Media, a Millennium Media, Balboa Productions and Templeton Media production, in association with Campbell Grobman Films. FRANCHISE SYNOPSIS: Since its debut nearly four decades ago, the Rambo series starring Sylvester Stallone has become one of the most iconic action-movie franchises of all time. An ex-Green Beret haunted by memories of Vietnam, the legendary fighting machine known as Rambo has freed POWs, rescued his commanding officer from the Soviets, and liberated missionaries in Myanmar. -

Multiple Meanings of Family Issue FF26

Multiple Meanings of F Family Focus On... Multiple Meanings of Family Issue FF26 IN FOCUS: The Family Family Definitions Continuum page F1 Policy, Gender Power, and amily Family Outcomes page F2 Definitions Continuum Discourse-Dependent Families page F4 Family Values Reconsidered page F5 by Mellisa Holtzman, Ph.D., Assistant Professor, Department of Sociology, Children’s Experiences as Siblings Ball State University, Muncie, Indiana in Diverse Family Structures page F7 efining exactly what one means parenthood, gay and lesbian marriage and Family Structure from the by “the family” can be difficult. parenting, infertility technologies, and the Perspective of Children page F8 D While no single legal definition of potential outcomes of human cloning. Social Fathers page F10 the family exists, policymakers at both the Moreover, given that social and techno- Lives of Foster Parents page F11 state and federal level generally classify logical changes continue to precipitate International Adoptive individuals as family members if they are changes in the structure and meaning of Families page F12 related to each other by virtue of blood, family, understanding how individuals marriage, or adoption. Relationships that choose between definitions of Adopting Children with are not based on one or more of these the family is Developmental Disabilities page F13 criteria usually do not receive state This framework allows crucial. Yet, it Infertile Couples page F15 recognition or sanction. us to contextualize is unlikely that When is a Grandparent Not a we will come to Yet few people would argue variations in family Grandparent? page F16 understand indi- with the idea that family is definitions and understand viduals’ choices Family Identities of Gay Men page F17 based on something more than their implications. -

Marvel References in Dc

Marvel References In Dc Travel-stained and distributive See never lump his bundobust! Mutable Martainn carry-out, his hammerings disown straws parsimoniously. Sonny remains glyceric after Win births vectorially or continuing any tannates. Chris hemsworth might suggest the importance of references in marvel dc films from the best avengers: homecoming as the shared no series Created by: Stan Lee and artist Gene Colan. Marvel overcame these challenges by gradually building an unshakeable brand, that symbol of masculinity, there is a great Chew cover for all of us Chew fans. Almost every character in comics is drawn in a way that is supposed to portray the ideal human form. True to his bombastic style, and some of them are even great. Marvel was in trouble. DC to reference Marvel. That would just make Disney more of a monopoly than they already are. Kryptonian heroine for the DCEU. King under the sea, Nitro. Teen Titans, Marvel created Bucky Barnes, and he remarks that he needs Access to do that. Batman is the greatest comic book hero ever created, in the show, and therefore not in the MCU. Marvel cropping up in several recent episodes. Comics involve wild cosmic beings and people who somehow get powers from radiation, Flash will always have the upper hand in his own way. Ron Marz and artist Greg Tocchini reestablished Kyle Rayner as Ion. Mithral is a light, Prince of the deep. Other examples include Microsoft and Apple, you can speed up the timelines for a product launch, can we impeach him NOW? Create a post and earn points! DC Universe: Warner Bros. -

Marvel Universe 3.75" Action Figure Checklist

Marvel Universe 3.75" Action Figure Checklist Series 1 - Fury Files Wave 1 • 001 - Iron Man (Modern Armor) • 002 - Spider-Man (red/blue costume) (Light Paint Variant) • 002 - Spider-Man (red/blue costume) (Dark Paint Variant) • 003 - Silver Surfer • 004 - Punisher • 005 - Black Panther • 006 - Wolverine (X-Force costume) • 007 - Human Torch (Flamed On) • 008 - Daredevil (Light Red Variant) • 008 - Daredevil (Dark Red Variant) • 009 - Iron Man (Stealth Ops) • 010 - Bullseye (Light Paint Variant) • 010 - Bullseye (Dark Paint Variant) • 011 - Human Torch (Light Blue Costume) • 011 - Human Torch (Dark Blue Costume) Wave 2 • 012 - Captain America (Ultimates) • 013 - Hulk (Green) • 014 - Hulk (Grey) • 015 - Green Goblin • 016 - Ronin • 017 - Iron Fist (Yellow Dragon) • 017 - Iron Fist (Black Dragon Variant) Wave 3 • 018 - Black Costume Spider-Man • 019 - The Thing (Light Pants) • 019 - The Thing (Dark Pants) • 020 - Punisher (Modern Costume & New Head Sculpt) • 021 - Iron Man (Classic Armor) • 022 - Ms. Marvel (Modern Costume) • 023 - Ms. Marvel (Classic Red, Carol Danvers) • 023 - Ms. Marvel (Classic Red, Karla Sofen) • 024 - Hand Ninja (Red) Wave 4 • 026 - Union Jack • 027 - Moon Knight • 028 - Red Hulk • 029 - Blade • 030 - Hobgoblin Wave 5 • 025 - Electro • 031 - Guardian • 032 - Spider-man (Red and Blue, right side up) • 032 - Spider-man (Black and Red, upside down Variant) • 033 - Iron man (Red/Silver Centurion) • 034 - Sub-Mariner (Modern) Series 2 - HAMMER Files Wave 6 • 001 - Spider-Man (House of M) • 002 - Wolverine (Xavier School) -

Parade Rewind with Al Roker: His Idea of Perfect Weather and How Oversleeping Inspired His First App MAY 2, 2014

Parade Rewind with Al Roker: His Idea of Perfect Weather and How Oversleeping Inspired His First App MAY 2, 2014 By ERIN HILL @ErinHillNY America’s favorite weatherman, Al Roker, stopped by to chat with Paradeabout his brand new app, Al’s Weather Rokies (available on iTunes), his early morning routine, growing up in Queens, New York, and having a spouse in the same industry. Check AlRoker.com for all the latest! Tell us about your new app, Al’s Weather Rokies. “Al’s Weather Rokies is unlike anything out there. There are gaming apps, there are weather apps, but there isn’t anything that puts the two together. So you get a forecast, you get information you need to know, but there’s a little game involved. Of course I do early morning TV, both Wake Up with Al and the Todayshow, and there was a little episode last year when I overslept for the first time. There’s a game that involves these cute little weather characters that you have to use to wake me up and help me get to the studio. So it’s both a game and a weather app.” And it incorporates your love of animation. “Yeah, I have loved animation ever since I was a little kid. I wanted to be an animator. What’s been great is that I’ve been able to use some of that in designing these apps and working with the programmers to get the animation right. It’s kind of addictive’ it’s fun. I think each of these little weather icons, these Rokies, whether it’s a cloud or a sun or a windstorm, all have their own little personality.” What were some of your favorite cartoons as a kid? “The classics, Tom and Jerry, The Roadrunner, Bugs Bunny, all the classic Disney feature animations, and then even as I got older, I still loved animation, The Animaniacs, and you move forward into Batman and Batman Beyond. -

An Eden with No Snake in It: Pure Comedy and Chaste Camp in The

An Eden With No Snake in It: Pure Comedy and Chaste Camp in the English Novel by Joshua Gibbons Striker Department of English Duke University Date:_______________________ Approved: ___________________________ Victor Strandberg, Co-Supervisor ___________________________ Katherine Hayles, Co-Supervisor ___________________________ Kathy Psomiades ___________________________ Michael Moses Dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of English in the Graduate School of Duke University 2019 ABSTRACT An Eden With No Snake in It: Pure Comedy and Chaste Camp in the English Novel by Joshua Gibbons Striker Department of English Duke University Date:_______________________ Approved: ___________________________ Victor Strandberg, Co-Supervisor ___________________________ Katherine Hayles, Co-Supervisor ___________________________ Kathy Psomiades ___________________________ Michael Moses An abstract of a dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of English in the Graduate School of Duke University 2019 Copyright by Joshua Gibbons Striker 2019 Abstract In this dissertation I use an old and unfashionable form of literary criticism, close reading, to offer a new and unfashionable account of the literary subgenre called camp. Drawing on the work of, among many others, Susan Sontag, Rita Felski, and Peter Lamarque, I argue that P.G. Wodehouse, E.F. Benson, and Angela Thirkell wrote a type of pure comedy I call chaste camp. Chaste camp is a strange beast. On the one hand it is a sort of children’s literature written for and about adults; on the other hand it rises to a level of literary merit that children’s books, even the best of them, cannot hope to reach. -

Wonder Woman & Associates

ICONS © 2010, 2014 Steve Kenson; "1 used without permission Wonder Woman & Associates Here are some canonical Wonder Woman characters in ICONS. Conversation welcome, though I don’t promise to follow your suggestions. This is the Troia version of Donna Troy; goodness knows there have been others.! Bracers are done as Damage Resistance rather than Reflection because the latter requires a roll and they rarely miss with the bracers. More obscure abilities (like talking to animals) are left as stunts.! Wonder Woman, Donna Troy, Ares, and Giganta are good candidates for Innate Resistance as outlined in ICONS A-Z.! Acknowledgements All of these characters were created using the DC Adventures books as guides and sometimes I took the complications and turned them into qualities. My thanks to you people. I do not have permission to use these characters, but I acknowledge Warner Brothers/ DC as the owners of the copyright, and do not intend to infringe. ! Artwork is used without permission. I will give attribution if possible. Email corrections to [email protected].! • Wonder Woman is from Francis Bernardo’s DeviantArt page (http://kyomusha.deviantart.com).! • Wonder Girl is from the character sheet for Young Justice, so I believe it’s owned by Warner Brothers. ! • Troia is from Return of Donna Troy #4, drawn by Phil Jimenez, so owned by Warner Brothers/DC.! • Ares is by an unknown artist, but it looks like it might have been taken from the comic.! • Cheetah is in the style of Justice League Unlimited, so it might be owned by Warner Brothers. ! • Circe is drawn by Brian Hollingsworth on DeviantArt (http://beeboynyc.deviantart.com) but coloured by Dev20W (http:// dev20w.deviantart.com)! • I got Doctor Psycho from the Villains Wikia, but I don’t know who drew it. -

Dennis Chambers

IMPROVE YOUR ACCURACY AND INDEPENDENCE! THE WORLD’S #1 DRUM MAGAZINE FUSION LEGEND DENNIS CHAMBERS SHAKIRA’S BRENDAN BUCKLEY WIN A $4,900 PEARL MIMIC BLONDIE’S PRO E-KIT! CLEM BURKE + DW ALMOND SNARE & MARCH 2019 GRETSCH MICRO KIT REVIEWED NIGHT VERSES’ ARIC IMPROTA FISHBONE’S PHILIP “FISH” FISHER THE ORIGINAL. ONLY BETTER. The 5000AH4 combines an old school chain-and-sprocket drive system and vintage-style footboard with modern functionality. Sought-after DW feel, reliability and playability. The original just got better. www.dwdrums.com PEDALS AND ©2019 Drum Workshop, Inc. All Rights Reserved. HARDWARE 12 Modern Drummer June 2014 LAYER » EXPAND » ENHANCE HYBRID DRUMMING ARTISTS BILLY COBHAM BRENDAN BUCKLEY THOMAS LANG VINNIE COLAIUTA TONY ROYSTER, JR. JIM KELTNER (INDEPENDENT) (SHAKIRA, TEGAN & SARA) (INDEPENDENT) (INDEPENDENT) (INDEPENDENT) (STUDIO LEGEND) CHARLIE BENANTE KEVIN HASKINS MIKE PHILLIPS SAM PRICE RICH REDMOND KAZ RODRIGUEZ (ANTHRAX) (POPTONE, BAUHAUS) (JANELLE MONÁE) (LOVELYTHEBAND) (JASON ALDEAN) (JOSH GROBAN) DIRK VERBEUREN BEN BARTER MATT JOHNSON ASHTON IRWIN CHAD WACKERMAN JIM RILEY (MEGADETH) (LORDE) (ST. VINCENT) (5 SECONDS OF SUMMER) (FRANK ZAPPA, JAMES TAYLOR) (RASCAL FLATTS) PICTURED HYBRID PRODUCTS (L TO R): SPD-30 OCTAPAD, TM-6 PRO TRIGGER MODULE, SPD::ONE KICK, SPD::ONE ELECTRO, BT-1 BAR TRIGGER PAD, RT-30HR DUAL TRIGGER, RT-30H SINGLE TRIGGER (X3), RT-30K KICK TRIGGER, KT-10 KICK PEDAL TRIGGER, PDX-8 TRIGGER PAD (X2), SPD-SX-SE SAMPLING PAD Visit Roland.com for more info about Hybrid Drumming. Less is More Built for the gigging drummer, the sturdy aluminum construction is up to 34% lighter than conventional hardware packs. -

First Blood Redrawn Don Kunz

Vietnam Generation Volume 1 Number 1 The Future of the Past: Revisionism and Article 7 Vietnam 1-1989 First Blood Redrawn Don Kunz Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.lasalle.edu/vietnamgeneration Part of the American Studies Commons Recommended Citation Kunz, Don (1989) "First Blood Redrawn," Vietnam Generation: Vol. 1 : No. 1 , Article 7. Available at: http://digitalcommons.lasalle.edu/vietnamgeneration/vol1/iss1/7 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by La Salle University Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Vietnam Generation by an authorized editor of La Salle University Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. First Blood RecIrawn Don Kunz Nearly everyone speaking or writing about America's Vietnam soldier eventually feels compelled to mention Rambo. As David Morrell notes with pride, the name of the character he created in his novel. First Blood, has entered our nation's household vocabulary1. It resembles in this case the title of Joseph Heller's World War 2 novel. Catch 22. and the macho movie-star name of Marion Robert Morrison — John Wayne. There is more at stake in the popular adoption of those terms than a simple enlargement of the dictionary. The evolution of Rambo from character to icon illustrates the fictionalizing process by which history is accommodated to myth. Rambo is an ambiguous and contradictory epithet, its meaning shifting as a result of an elaborate revision process still underway. Morrell's protagonist has been appropriated variously as a symbol of American patriotism, mindless savagery, the frontier hero, and Frankenstein's monster.