Extractive Industries and Protected Areas in Central Africa: for Better Or for Worse?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Assessing Impacts of Forest Governance Interventions: Learning from World Bank Experience

MAY 2014 A PROFOR WORKING PAPER PROFOR WORKING PAPER ASSESSING IMPACTS OF FOREST GOVERNANCE INTERVENTIONS: LEARNING FROM WORLD BANK EXPERIENCE Nalin Kishor Maria Ana de Rijk ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This report has been prepared by Nalin Kishor and Maria Ana de Rijk. Helpful comments and suggestions were received from Aparajita Goyal, Arianna Legovini, Avjeet Singh, Dan Miller, Dan Stein, Diji Chandrasekharan Behr, Ijeoma Emenanjo, Peter Jipp, Selene Castillo and Tuukka Castrén and Valerie Hickey. Veronica Jarrin provided operational support since the inception of this activity. Sujatha Venkat Ganeshan provided editorial, layout and publication support. This work was funded by the Program on Forests (PROFOR), a multi-donor partnership managed by a Secretariat at the World Bank. PROFOR finances forest-related analysis and processes that support the following goals: improving people’s livelihoods through better management of forests and trees; enhancing forest governance and slaw enforcement; financing sustainable forest management; and coordinating forest policy across sectors. Learn more at www.profor.info. DISCLAIMER All omissions and inaccuracies in this document are the responsibility of the authors. The views expressed do not necessarily represent those of the institutions involved, nor do they necessarily represent official policies of PROFOR or the World Bank. SUGGESTED CITATION Kishor, Nalin and Maria Ana de Rijk, 2014. Assessing impacts of forest governance interventions: Learning from World Bank experience. Washington DC: Program on Forests (PROFOR). Material in this paper can be copied and quoted freely provided acknowledgment is given. For a full list of publications please contact: Program on Forests (PROFOR) 1818 H Street, NW Washington, DC 20433, USA [email protected] www.profor.info/knowledge PROFOR is a multi-donor partnership supported by the European Commission, Finland, Germany, Italy, Japan, the Netherlands, Switzerland, the United Kingdom and the World Bank. -

Wildlife Trafficking in Cameroon and Republic of the Congo

Wildlife Traffcking in Cameroon and Republic of the Congo A Scoping Review and Recommendations for Cooperation with China A / Room 032, unit 1, foreign affairs offce building, tower garden, No. 14, South Liangmahe Road, Chaoyang District, Beijing P.C / 100600 T / 86-10-8532-5910 F / 86-10-8532-5038 E / [email protected] http://www.geichina.org Acknowledgement We would like to give special thanks to UK’s Department for International Development (DFID) for its funding support on this project. We are very grateful of Mr. Simon Essissima from the Ministry of Forestry and Wildlife of Cameroon and Mr. Nan Jiang from the Nanjing Forest Police College of China for their invaluable feedbacks and suggestions to the report. We would also like to thank Mme. Jiaman Jin, Executive Director of GEI, Mr. Chun Li, Senior Consultant of GEI, Mr. Peng Ren, Program Manager of Overseas Investment, Trade and the Environment, and Ms. Lin Ji, Executive Secretary of GEI for their guidance, support and participation throughout the research project. Finally, we would like to thank our interns who have contributed to the translation and editing of this report: Ms. Qiuyi Wang, Ms. Qian Zhu, Ms. Diana Gomez. 01 02 Acronyms Introduction ACFAP Congolese Wildlife and Protected Areas Agency [1] Wildlife traffcking is increasingly considered a threat to global conservation efforts. With global momentum to combat international wildlife traffcking, countries along the ANAFOR National Forest Development Support Agency "Congo Basin Forests," Greenpeace supply chain should take collective action to ensure effective disruption of the traffcking CAR Central African Republic USA, accessed August 09, 2019. -

Shaping the Debate on Forests and Climate Change in Central Africa

FOREST DAY SUMMARY REPORT FOREST DAY CENTRAL AFRICA Shaping the Debate on Forests and Climate Change in Central Africa 24 April 2008, Palais des Congrès, Yaounde, Cameroon. The Center for International Forestry Research (CIFOR), organized “Forest Day Central Africa” on 24 April 2008 in Yaounde, Cameroon. This event was a follow up of Forest Day Bali, organized by CIFOR in parallel with the 13th meeting of the Conference of the Parties to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (COP13-UNFCCC). The theme for Forest Day Central Africa was “Shaping the Debate on Forests and Climate Change in Central Africa ”. The aim was to raise awareness and share knowledge and experiences on Reduced Emissions from Deforestation and forest Degradation (REDD) in Central Africa. This was achieved by bringing together researchers, NGOs, the private sector, forest communities and government officials to engage in dialogue about the issue. The first of its kind in Central Africa, Forest Day was attended by more than 150 people, including scientists, policymakers and representatives from various intergovernmental and non –governmental organizations. Results from a survey show that participants highly appreciated the event: of the 44 survey forms that were filled in, 21 people rated Forest Day as very good, 20 as good. In addition to opening and closing plenaries, the event comprised of four parallel sessions and a Forest Café. The themes of the four parallel sessions were: REDD and other forest management approaches in Central Africa; Methods, difficulties and results of forestry dynamics; the impact of REDD on rural poverty; REDD, markets and governance. -

Wood and Paper-Based Products

Wood and www.SustainableForestProds.org Paper-Based Products Sustainable Procurement of Sustainable Procurement of Wood and Guide and resource kit Paper-based Products World Business Council for Sustainable Development – WBCSD Guide and resource kit Chemin de Conches 4, 1231 Conches-Geneva, Switzerland Version 2 Update June 2011 Tel: (41 22) 839 31 00, Fax: (41 22) 839 31 31, E-mail: [email protected], Web: www.wbcsd.org VAT nr. 644 905 WBCSD US, Inc. 1500 K Street NW, Suite 850, Washington, DC 20005, US Tel: +1 202 383 9505, E-mail: [email protected] World Resources Institute – WRI 10 G Street, NE (Suite 800), Washington DC 2002, United States Tel: (1 202) 729 76 00, Fax: (1 202) 729 76 10, E-mail: [email protected], Web: www.wri.org www.SustainableForestProds.org Sourcing and legality aspects Origin Where do the products come from? Information accuracy Is information about the products credible? Legality Have the products been legally produced? Environmental aspects Social aspects Sustainability Local communities Have forests been sustainably and indigenous peoples managed? Have the needs of local communities or indigenous peoples Special places been addressed? Have special places, including sensitive ecosystems, been protected? Climate change Have climate issues been addressed? Environmental protection Have appropriate environmental controls been applied? Recycled fiber Has recycled fiber been used appropriately? Other resources Have other resources been used appropriately? Contributing Authors Partnership Disclaimer Disclaimer Ordering -

Atelier Regional Oibt/Cites Sur L'afrormosia

TO ENSURE THAT THE INTERNATIONAL TRADE IN AFRORMOSIA TIMBER IS NOT DETRIMENTAL TO ITS CONSERVATION Report on the Regional Workshop on the international trade in Pericopsis elata (afrormosia or assamela) timber Hôtel Palm Beach, Kribi, Cameroon, 2 - 4 April 2008 ITTO/CITES Project on the Sustainable Management of Afrormosia in the Congo Basin Photos: plantation (left) & stem (right) of Pericopsis elata neer Kribi, Cameroon, by J. Ngueguim (IRAD) FULL REPORT ON THE REGIONAL OIBT/CITES WORKSHOP ON AFRORMOSIA 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF CONTENTS.................................................................................................................................................... 3 SUMMARY........................................................................................................................................................................ 4 1. INTRODUCTION .......................................................................................................................................................... 5 1.1. General background and issues .............................................................................................................................. 5 1.2. Goals of the workshop ........................................................................................................................................... 5 2. CONDUCT OF THE WORKSHOP ............................................................................................................................... 6 2.1. Ceremonial phase -

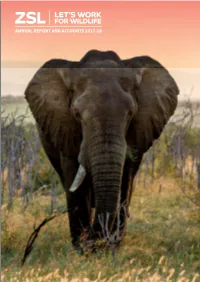

Annual Report and Accounts 2017-18 and Accounts Report Annual

ANNUAL REPORT AND ACCOUNTS 2017-18 AND ACCOUNTS REPORT ANNUAL ZSL Annual Report and Accounts | 2017-18 The living collections at ZSL Zoos – such as this spectacular red-crested turaco – help CONTENTS to engage our audiences with wildlife Welcome 3 Our impacts at a glance 4 Objectives and activities ZSL 200: Our new strategy, vision, purpose and priorities 6 A world where wildlife thrives 8 Achievements and performance Working around the world 10 Our Zoos 12 Monitoring our planet 14 Developing conservation technology 16 Saving threatened species 18 Improving wildlife health 20 Conservation for communities 22 Engaging with business 24 Encouraging lifelong learning 26 Making our work possible 28 Plans for the future Looking ahead 32 Supporting ZSL Supporting our work 34 Our supporters 36 Financial review and Governance Financial summary 38 Principal risks and uncertainties 44 Governance 46 Independent Auditor’s Report 48 Financial Statements 49 2 ZSL Annual Report and Accounts 2017-18 zsl.org WELCOME Welcome The President and Director General of The Zoological Society of London introduce our review of May 2017 to April 2018. s President of The Zoological Society of London y priority as incoming Director General of the (ZSL), I am delighted to present our 2017-18 Annual world’s first and foremost zoological society Report. This marks the third year of my Presidency, has been to ensure we have a strategy in and I take great pride in being part of a conservation place as we move towards our third century of organisation like ours that continues to act as the working for wildlife. -

Geographical and Subject Index

Index Geographical and Subject Index J\[`d\ekXip 9Xjj`ej E @ek\i`fiYXj`e N < :fdgfj`k\Xe[Zfdgc\oYXj`ej I`]kYXj`e J ;fnenXigYXj`e DXi^`eXcjX^figlcc$XgXikYXj`ej D\[`XeXe[jlY[lZk`feYXj`ej ;\ckX DXafi]iXZkli\qfe\j Geographical Index A B Abd-Al-Kuri (Socotra) 224 Bab el Mandeb (Sudan) 241 Aberdares (Kenya) 136 Babadougou (Ivory Coast) 130 Abidjan (Ivory Coast) 128 Babassa (Central African Republic) 68 Abkorum-Azelik (Niger) 192 Baddredin (Egypt) 96 Abu Ras Plateau (Egypt) 94 Bahariya Oasis (Egypt) 95, 96 Abu Tartur (Egypt) 94, 96 Bakouma (Central African Republic) 68 Abu Zawal (Egypt) 94 Bamako (Mali) 165 Abuja (Nigeria) 196 Bandiagara (Mali) 165 Accra (Ghana) 119 Bangui (Central African Republic) 68 Acholi region (Uganda) 265 Bangweulu Swamp (Zambia) 270 Adrar des Iforas (Algeria) 32, 34 Banjul (Gambia) 114 Addis Ababa (Ethiopia) 106 Baragoi (Kenya) 134 Ader-Doutchi (Niger) 193 Barberton Mountains (South Africa) 230 Adola (Ethiopia) 108 Basila (Benin) 44 Adrar (Mauritania) 169 Bation Peak (Kenya) 135 Adrar des Iforas Mountains (Mali) 162 Batoka Gorge (Zambia) 270 Adua-Axum (Ethiopia) 106 Bayuda Desert (Sudan) 238, 240 Afast (Niger) 192 Beghemder (Ethiopia) 106 Agadez (Niger) 192, 193 Benghazi (Libya) 150 Agadir (Morocco) 176 Bengo (Angola) 41 Agbaja Plateau (Nigeria) 196 Benty (Guinea) 124 Ahnet (Algeria) 34 Benue Valley (Nigeria) 196 AÏr Massif 190, 193 Biankouma (Ivory Coast) 130 Akagera (Rwanda) 206 Bidzar (Cameroon) 60 Akoufa (Niger) 192 Bie (Angola) 41 Alexandra Peak (Uganda) 264 Big Hole (South Africa) 234, 235 Algerian Atlas (Algeria) -

Uranium Deposits in Africa: Geology and Exploration

Uranium Deposits in Africa: Geology and Exploration PROCEEDINGS OF A REGIONAL ADVISORY GROUP MEETING LUSAKA, 14-18 NOVEMBER 1977 tm INTERNATIONAL ATOMIC ENERGY AGENCY, VIENNA, 1979 The cover picture shows the uranium deposits and major occurrences in Africa. URANIUM DEPOSITS IN AFRICA: GEOLOGY AND EXPLORATION The following States are Members of the International Atomic Energy Agency: AFGHANISTAN HOLY SEE PHILIPPINES ALBANIA HUNGARY POLAND ALGERIA ICELAND PORTUGAL ARGENTINA INDIA QATAR AUSTRALIA INDONESIA ROMANIA AUSTRIA IRAN SAUDI ARABIA BANGLADESH IRAQ SENEGAL BELGIUM IRELAND SIERRA LEONE BOLIVIA ISRAEL SINGAPORE BRAZIL ITALY SOUTH AFRICA BULGARIA IVORY COAST SPAIN BURMA JAMAICA SRI LANKA BYELORUSSIAN SOVIET JAPAN SUDAN SOCIALIST REPUBLIC JORDAN SWEDEN CANADA KENYA SWITZERLAND CHILE KOREA, REPUBLIC OF SYRIAN ARAB REPUBLIC COLOMBIA KUWAIT THAILAND COSTA RICA LEBANON TUNISIA CUBA LIBERIA TURKEY CYPRUS LIBYAN ARAB JAMAHIRIYA UGANDA CZECHOSLOVAKIA LIECHTENSTEIN UKRAINIAN SOVIET SOCIALIST DEMOCRATIC KAMPUCHEA LUXEMBOURG REPUBLIC DEMOCRATIC PEOPLE'S MADAGASCAR UNION OF SOVIET SOCIALIST REPUBLIC OF KOREA MALAYSIA REPUBLICS DENMARK MALI UNITED ARAB EMIRATES DOMINICAN REPUBLIC MAURITIUS UNITED KINGDOM OF GREAT ECUADOR MEXICO BRITAIN AND NORTHERN EGYPT MONACO IRELAND EL SALVADOR MONGOLIA UNITED REPUBLIC OF ETHIOPIA MOROCCO CAMEROON FINLAND NETHERLANDS UNITED REPUBLIC OF FRANCE NEW ZEALAND TANZANIA GABON NICARAGUA UNITED STATES OF AMERICA GERMAN DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC NIGER URUGUAY GERMANY, FEDERAL REPUBLIC OF NIGERIA VENEZUELA GHANA NORWAY VIET NAM GREECE PAKISTAN YUGOSLAVIA GUATEMALA PANAMA ZAIRE HAITI PARAGUAY ZAMBIA PERU The Agency's Statute was approved on 23 October 1956 by the Conference on the Statute of the IAEA held at United Nations Headquarters, New York; it entered into force on 29 July 1957. The Headquarters of the Agency are situated in Vienna. -

Predicting the Effects of Climate Change on Species Distributions and Creating Reserve Networks: a Review of Tools and Methods

Durham E-Theses Adapting Protected Area Networks to the Impacts of Climate Change: Potential Options for the Sub-Saharan Africa Important Bird Area (IBA) Network FRATER, GEORGE,KENNETH,CHARLES How to cite: FRATER, GEORGE,KENNETH,CHARLES (2009) Adapting Protected Area Networks to the Impacts of Climate Change: Potential Options for the Sub-Saharan Africa Important Bird Area (IBA) Network, Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/200/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk 2 Adapting Protected Area Networks to the Impacts of Climate Change: Potential Options for the Sub-Saharan Africa Important Bird Area (IBA) Network George Frater School of Biological and Biomedical Sciences, Durham University 2009 This Thesis is submitted in candidature for the degree of Master of Science Declaration The material contained within this thesis has not previously been submitted for a degree at Durham University or any other University. -

Page a (First Section 1-12)

RAP Publication 2004/16 PROCEEDINGS OF THE SECOND INTERNATIONAL SYMPOSIUM ON THE MANAGEMENT OF LARGE RIVERS FOR FISHERIES VOLUME 1 Sustaining Livelihoods and Biodiversity in the New Millennium 11–14 February 2003, Phnom Penh, Kingdom of Cambodia Edited by Robin L. Welcomme and T. Petr FOOD AND AGRICULTURE ORGANIZATION OF THE UNITED NATIONS & THE MEKONG RIVER COMMISSION, 2004 III DISCLAIMER The designations employed and the presentation of the material in this document do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) and the Mekong River Commission (MRC) concerning the legal or constitutional status of any country, territory or sea area or concerning the delimitation of frontiers or boundaries. NOTICE OF COPYRIGHT All rights reserved Food & Agriculture Organization of the United Nations and Mekong River Commission. Reproduction and dissemination of material in this infor- mation product for educational or other non-commercial purposes are authorized without any prior written permis- sion from the copyright holders provided the source is fully acknowledged. Reproduction of material in this information product for resale or other commercial pur- poses is prohibited without written permission of the copyright holders. Application for such permission should be addressed to the Aquaculture Officer, FAO Regional Office for Asia and the Pacific, Maliwan Mansion, 39 Phra Athit Road, Bangkok 10200, Thailand. Images courtesy of the Mekong River Commission Fisheries Programme © FAO & MRC 2004 V ORIGINS of the SYMPOSIUM The Second International Symposium on the Management of Large Rivers for Fisheries was held on 11 – 14 February 2003 in Phnom Penh, Kingdom of Cambodia. -

2Nd Colloquium of the International Geoscience Program IGCP638

2nd Colloquium of the International Geoscience Program IGCP638 Geodynamics and mineralizations of paleoproterozoic formations for a sustainable development Casablanca, 07th-12th November 2017 Parrainé par l’UNESCO Organisé par L'Université Hassan II de Casablanca Faculté des Sciences Aïn Chock IGCP638 Leaders: Tahar AÏFA / Rennes 1 University (France) Omar SADDIQI / Hassan II Casablanca University (Morocco) Moussa DABO/ Cheikh Anta Diop University, Dakar (Senegal) http://igcp638.univ-rennes1.fr ORGANIZING COMMITTEE Omar Saddiqi (FSAC UH2C Casablanca): Chairman Lahssen Baidder (FSAC UH2C Casablanca) EL Hassan El Arabi (FSAC UH2C Casablanca) Aboubaker Farah (FSAC UH2C Casablanca) Faouziya Haissen ( FSBM UH2C Casablanca) Atika Hilali (FSAC UH2C Casablanca) Abdelhadi Kaoukaya (FSAC UH2C Casablanca) Mehdi Mansour (FSAC UH2C Casablanca) Mostafa Oukassou (FSBM UH2C Casablanca) Hassan Rhinane (FSAC UH2C Casablanca) SCIENTIFIC COMMITTEE Tahar Aïfa (Univ. Rennes 1, France) Alain Kouamelan (Univ. Abidjan, Ivory Coast) Mohammed Aissa (UMS Meknès, Morocco) Théophile Lasm (Univ. Abidjan, Ivory Coast) Laurent Ameglio (GyroLAG Potchefstroom, South Africa/ Jean-Pierre Lefort (Univ. Rennes 1, France) Perth, Australia) Addi Azza (Conseiller du Ministre de l’Energie, des Mines Ulf Linnemann (Unv. Dresden, Germany) et du Développement Durable, Rabat, Morocco) David Baratoux (IRD/UPS/IFAN, France) Khalidou Lo (Univ. Nouakchott, Mauritania) Lahssen Baidder (UH2C Casablanca, Morocco) Martin Lompo (Univ. Ouagadougou, Burkina Faso) Lenka Baratoux (IRD/IFAN, France) Lhou Maacha (Managem Casablanca, Morocco) Jocelyn Barbarand (UPS Orsay, France) Younes Maamar (Managem Casablanca, Morocco) Fernando Bea (Univ. of Granada, Spain) Henrique Masquelin (Univ. Montevideo, Uruguay) Mouloud Benbrahim (Univ. of Oran, Algeria) Sharad Master (Univ. Johannesburg, South Africa) Mohammed Bouabdellah (UMP Oujda, Morocco) Nacer Merabet (CRAAG Algiers, Algeria) Jean-Louis Boudinier (Univ. -

Climate Change in the Mount Cameroon National Park Region: Local Perceptions, Natural Resources and Adaptation Strategies, the Republic of Cameroon

DOCTORAL THESIS CLIMATE CHANGE IN THE MOUNT CAMEROON NATIONAL PARK REGION: LOCAL PERCEPTIONS, NATURAL RESOURCES AND ADAPTATION STRATEGIES, THE REPUBLIC OF CAMEROON A thesis approved by the Institute of Geography, University of Augsburg Germany, in fulfilment of the degree of Doctor of Natural Sciences - Dr.rer.nat. Institute of Geography, University of Augsburg, Germany By Vivian Njole Ntoko Supervised by Supervisor: Prof. Dr. Matthias Schmidt Co-supervisor: Prof. Dr. Karin Thieme Oral examination date June 25th, 2020 ABSTRACT Climate change is influencing indigenous communities in the Global South, and it is the object of a dominant global discourse. It is particularly important to pay attention to its impact on natural resources and people’s livelihoods. Local knowledge on how forest-dependent households and communities, especially those in tropical areas, see, respond and adjust to climate change and events is useful in developing strategies to support livelihoods, biodiversity conservation, climate change adaptation and policies. However, local perceptions of climate change remain largely unexplored and are subject to various interpretations. This study analyses the perceptions of indigenous people around the Mount Cameroon National Park (MCNP) on the impacts of climate change on livelihoods and natural resources, and the adaptation strategies to climate change utilised by individuals, groups and communities in this regard. This is achieved through the use of quantitative and qualitative methods for data collection. The quantitative methods entail a questionnaire survey randomly administered to 200 respondents in the study villages. The qualitative methods include participatory rural appraisal (PRA) tools, analysed using MAXQDA software. The research findings indicate that the MCNP region is endowed with fauna and flora species vital to indigenous livelihoods and the national economy, but they have decreased due to climatic and non-climate threats.